Catalysis

In chemistry and chemical engineering, catalysis is a process that uses an outside substance (the catalyst) to accelerate the rate of a chemical reaction through an uninterrupted and repeated cycle of elementary steps until the last step regenerates the catalyst in its original form. The catalyst is usually present in relatively small amounts and none of it is consumed in the process.[1] In the chemical process industries, catalytic processes are of great economic importance with the petroleum industry being the largest single user.

Many substances can act as catalysts, including: metals (in particular, transition metals), chemical compounds (e.g., metal oxides, sulfides, nitrides), organometallic complexes, and enzymes. Although a catalyst may be a gas, liquid or solid, most catalysts used in industrial chemical reactions are heterogeneous (see below) and are in the form of porous pellets. Since not all parts of a solid catalyst participate in the catalysis cycle, those parts that do participate are referred to as active sites. A single porous pellet may have 1018 active catalytic sites.[1]

This article does not discuss enzymatic or biochemical catalysis (for information on those types of catalysis, see the enzyme, biochemistry and organocatalysis articles).

The catalysis mechanism

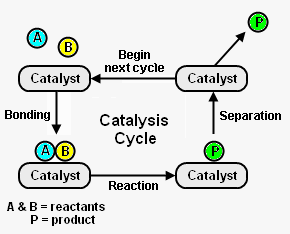

Figure 1 depicts the steps in a typical catalysis cycle. As depicted, the reactant molecules A and B are reacted to yield a desired product P. The catalysis cycle starts with the bonding of reactant molecules A and B to the catalyst. In the figure the catalyst is shown as a small piece of solid (heterogeneous catalysis) to which A and B are adsorbed, but the catalyst can also be a compound C dissolved in the reacting mixture (homogeneous catalysis). In that case, A and B are temporarily chemically bound to C. A and B then react, while bound to the catalyst C, to yield product P which is also bound to C. In the last step, the catalyst C is regenerated by product P separating from it. By physical or chemical separation methods the desired product P is removed from the mixture. The regenerated catalyst C then begins the cycle again by bonding with two new reactant molecules. [2]

In chemistry, activation energy[4] is the energy that must be overcome in order for a chemical reaction to occur. Activation energy may also be defined as the minimum energy required to start a designated chemical reaction. It is denoted by Ea in units of kilojoules per mole (kJ/mol). It may be thought of as the energy barrier that must be overcome to start a chemical reaction. According to Arrhenius' theory the speed of reaction depends exponentially (very steeply) on the height of the energy (also known as transition) barrier. A small lowering of transition barrier can yield a drastic increase in speed.

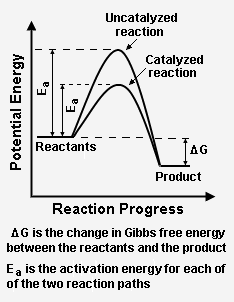

For a chemical reaction to proceed at a reasonable rate, there should exist an appreciable number of reactant species (molecules, atoms, ions, etc.) with energy equal to or greater than the activation energy of the reaction, which means that the temperature of the reactants must be so high that enough of the reactant species have a thermal energy that is sufficient to overcome the barrier. The higher the temperature, the more molecules (or atoms, etc.) have this energy and will react, and the faster the reaction proceeds. That is, reaction speed is strongly (in fact exponentially) dependent on temperature.[3] A catalyst does not lower the activation energy for a reaction, instead it provides an alternative path for the reaction that has a lower activation energy. The catalyst changes the chemical kinetics of a reaction but not the chemical thermodynamics. The thermodynamic (Gibbs free) energy of the reactants and products is not affected by the presence of the catalyst.

Figure 2 depicts how a catalyzed reaction follows a lower activation energy path than the higher activation energy path followed by the same reaction when it is not catalyzed. Overall, both the catalyzed path and the uncatalyzed path have the same change in Gibbs free energy between the reactants and the reaction product.

The energy diagram in Figure 2 illustrates several important points:[2]

- The presence of the catalyst provides an alternative reaction path, which is definitely more complex (see Figure 1) because it involves the catalyst, but energetically much more favorable.

- The activation energy of the catalyzed reaction is significantly smaller than that of the uncatalyzed reaction. Given its exponential dependence on activation energy, the rate of the catalyzed reaction is much higher.

- Since the overall change in Gibbs free energy is the same for the catalyzed reaction as for the uncatalyzed reaction, the reaction equilibrium constant (which is a function of the Gibbs free energies of reactants and products only) is not affected by the catalyst. As noted above, the catalyst does not change the chemical thermodynamics of the reaction. Thus, if a reaction is thermodynamically unfavorable, the catalyst cannot change that situation.

The term "turn over frequency" (TOF) is used quite commonly in the technical literature to characterize the activity of catalysts. However, the definition of TOF in the literature is not consistent and varies quite widely. For example, two of the definitions in the literature are (the first is often used for homogeneous and the second for heterogeneous catalysis):

- Moles of product formed per second per mole of catalyst[5]

- Moles of reactants converted per second per active site.[2]

In both of the above definitions, the unit of time is sometimes designated as an hour rather than a second.

Another catalytic activity term is the katal, an SI derived unit, which is used mostly in biochemistry to characterize the activity of enzymes.[6]

Types of catalysis and examples

Catalysis can be categorized into two main types: heterogeneous and homogeneous. In heterogeneous catalysis, the catalyst is in one phase[7] while the reactants and products are in a different phase or, for some cases, two different phases. In homogeneous catalysis, the catalyst is in the same phase as the reactants and the products.[8]

Heterogeneous catalysis [8][9][10]

Typical examples of heterogeneous catalysis involve a solid catalyst with the reactants as either liquids or gases. Separation of the products from the catalyst is relatively easy. However, the catalyst in heterogeneous catalysis is often less selective than in homogeneous catalysis.

A few specific examples of heterogeneous catalysis are:[8][9][10]

- The catalytic converters in automobiles convert exhaust gases such as carbon monoxide (CO) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) into more harmless gases like carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitrogen (N2). Metals (solids) like platinum (Pt), palladium (Pd) and rhodium (Rh) are used as the catalyst. The metals are deposited as thin layers onto a ceramic honeycomb. This maximizes the surface area and keeps the amount of metal used to a minimum.

- The large-scale industrial processes for manufacturing sulfuric acid (H2SO4) involve using solid vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) as the catalyst to convert gaseous sulfur dioxide (SO2) into gaseous sulfur trioxide (SO3).

- The catalytic hydrogenation of liquid unsaturated hydrocarbons (alkenes) by reacting them with gaseous hydrogen (H2) to produce liquid saturated hydrocarbons (alkanes) uses metals like platinum (Pt) and palladium (Pd) as the catalyst. This is an example of three-phase catalysis, the catalyst being a solid and one of the reactants being a gas while another reactant and the product are liquids.

- The Haber process N2+3H2 → 2NH3. The catalyst is porous iron prepared by reducing magnetite, Fe3O4, with potassium hydroxide (KOH) added as a promoter (see below).

Homogeneous catalysis [8][9][10]

Typical examples of homogeneous catalysis have the catalyst, reactant and products all present as a gas or contained in a single liquid phase. Separation of the products from the catalyst is relatively difficult. However, the catalyst in homogeneous catalysis is often more selective than in heterogeneous catalysis.

A few examples of homogeneous catalysts are:[8][9][10]

- The depletion of ozone (O3) in the ozone layer of the Earth's atmosphere by chlorine free radicals (Cl·) is a an example where everything is present in a gas phase. The chlorine free radicals, derived from the slow breakdown of man-made chlorofluorohydrocarbons (CFCs) like CCl2F2 released into the atmosphere, acts both as a reactant and the catalyst in converting gaseous ozone to gaseous oxygen (O2).

- The production of an ester by reacting a carboxylic acid with an alcohol involves the use of sulfuric acid as the catalyst and is an example where everything is contained in a liquid phase. This reaction is known a Fischer esterification, named after the German chemist Hermann Emil Fischer (1852 - 1919).

Promoters, inhibitors and poisons

Promoters are substances, small amounts of which can increase the activity of a catalyst. For example, the activity of the iron (Fe) catalyst used in the Haber process for ammonia synthesis is increased by the addition of a small amount of potassium (K) as a promoter.

Small amounts of some substances can reduce the the activity a catalyst. If the reduction in activity is reversible, the substances are called inhibitors. If the reduction in activity is irreversible, the substances are called poisons.[11]

Inhibitors are sometimes used to increase the selectivity of a catalyst by retarding undesirable reactions. For example, the conversion of acetylene (C2H2) to ethylene (C2H4) by catalytic hydrogenation uses palladium as the catalyst and lead acetate (Pb(CH3COO)2) as the inhibitor. Without the partial deactivation of the catalyst by the inhibitor, the ethylene produced would be further hydrogenated to undesirable ethane.

As an example of the precautions taken to avoid catalyst poisoning, the expensive platinum (Pt) and rhenium (Re) catalyst in the catalytic reforming process for producing high-quality gasoline in petroleum refineries is subject to irreversible deactivation by sulphur, nitrogen and arsenic compounds. Because of that, the petroleum naphtha feedstocks to catalytic reformers are always processed for removal of such compounds prior to being fed to the reformers.

Applications

Petroleum refining

- Fluid catalytic cracking: Breaking large hydrocarbon molecules into smaller ones

- Catalytic reforming: Reforming molecules to produce high quality gasoline component

- Hydrodesulfurization: Removing sulfur compounds from refinery intermediate products

- Hydrocracking: Breaking large hydrocarbon molecules into smaller ones

- Alkylation: Converting isobutane and butylenes into a high-quality gasoline component

- Isomerization: Converting pentane into a high-quality gasoline component

- Claus process: Convering gaseous hydrogen sulphide into elemental sulphur

Chemicals and petrochemicals

- Steam reforming for hydrogen production

- Haber process for ammonia production

- Styrene and Butadiene synthesis for use in producing synthetic rubber

- Contact process for production of sulfuric acid

- Ostwald process for production of nitric acid

- Methanol synthesis

- Various processes for producing many different plastics and synthetic fabrics

Other

- Catalytic converters for mitigating automobile exhaust emissions

- Fischer-Tropsch and Coal gasification processes for producing synthetic fuel gases and liquid fuels

- Various processes for producing many different medicines

History

Catalysts had been used in the laboratory before 1800 by Joseph Priestly in England and by the Dutch chemist Martinus van Marum, both of whom made observations on the dehyrogenation of alcohol with metal catalysts. However, it seems that both of them regarded the metal merely as a source of heat.

These are some of the chemists whose work during the 1800's led to the development of the modern catalyst technology:[12][13]

- In 1806, the French chemists Charles Bernard Désormes and his son-in-law Nicolas Clément made perhaps the first attempt to propose a theory of catalysis based on the catalytic effect of nitrogen oxides in the lead chamber process for the manufacture of sulfuric acid.[14]

- In 1813, the French chemist Louis Jacques Thénard discovered that ammonia is entirely decomposed into nitrogen and hydrogen when passed over various red-hot metals.

- In 1817, Sir Humphrey Davy, an English chemist, published a paper about his work with flameless oxidation of coal gas in the presence of preheated, hot platinum wires. That paper contained perhaps the first clear realization that chemical reaction between two gaseous reactants can occur on a metal surface without the metal being chemically changed.[15]

- In 1820, Edmund Davy, a chemistry professor at Cork in Ireland and a cousin of Sir Humphrey Davy, prepared a finally divided platinum catalyst which had such high activity that it acted at room temperature without any preheating.

- In 1823, Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner, a chemistry professor at the University of Jena in Germany demonstrated that hydrogen and atmospheric air ignited spontaneously in the presence of a platinum sponge.[16][17] He then applied his work to construct a fire stick (or Feuerzeug in German) which was a fire lighter based on hydrogen and a catalyst of platinum sponge that became a commercial success in the 1820s.

- In 1836, the Swedish chemist Jöns Jakob Berzelius coined the term catalysis to describe the effect that reactions are accelerated by substances that remain unchanged after the reaction.[18][19]

- In 1838, C.F. Kuhlmann of France first oxidized ammonia using a platinum catalyst to produce nitrogen oxides which he then absorbed in water to produce nitric acid. However, his process was not then commercialized because ammonia was too expensive at that time compared to the Chile saltpetre (potassium nitrate) being used at that time to produce nitric acid.

- In the 1880s, Wilhelm Ostwald at Leipzig University in Germany started a systematic investigation into reactions that were catalyzed by the presence of acids and bases, and found that chemical reactions occur at finite rates and that these rates can be used to determine the strengths of acids and bases.

- In 1894 Ostwald gave the first modern definition:[20] Catalysis is the acceleration of a chemical reaction, which proceeds slowly, by the presence of a foreign substance. For his work on catalysis, Ostwald was awarded the 1909 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[21]

From these early beginnings, large industries have arisen and a vast body of scientific information has been accumulated. The economic contribution from catalysis is as remarkable as the phenomenon itself. Four sectors of the world’s economy are petroleum, energy production, chemicals production, and the food industry; and they are all critically dependent on the use of catalysts. Estimates are that catalysis contributes to greater than 35% of global GDP; the biggest part of this contribution comes from the generation of high energy fuels which depend on the use of small amounts of catalysts in the world’s petroleum refineries.[22]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Applications (CPSMA), National Academies (1992). Catalysis Looks to the Future. National Academies Press. ISBN 0-309-04584-3. Available online at Executive Summary

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 I. Chorkendorff and J. W. Niemantsverdriet (2007). Concepts of Modern Catalysts and Kinetics, 2nd Edition. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-31672-8.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The Effect of Catalysts on Reaction Rates From a website provided by Jim Clarke, retired Head of Chemistry and then Head of Science at Truro School in Cornwall, United Kingdom.

- ↑ A term introduced in 1889 by the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius

- ↑ Hideo Kurosawa and Akio Yamamoto (2003). Fundamentals of Molecular Catalysis, 1st Edition. Elsevier Science. ISBN 0-444-50921-6.

- ↑ R. Dybkaer (2001). "Unit "katal" for Catalytic Activity (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure Appl. Chem. 73 (6): 927-931.

- ↑ If a boundary exists between the catalyst and the reaction system (i.e., the reactants and the products), then the system has two phases. In this context, a phase is different from the most familiar states of matter: solid, liquids and gases. For example, if a liquid catalyst and a liquid reaction system were mutually insoluble, a boundary would exist between the catalyst and the reaction system. That would constitute two phases in the context of catalysis whereas it would be considered as being one state of matter, namely a liquid.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Types of Catalysis From a website provided by Jim Clarke, retired Head of Chemistry and then Head of Science at Truro School in Cornwall, United Kingdom.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Chemistry Explained Chemistry Encyclopedia

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Catalyst Lecture 12 Faculty of Chemistry, Silesian University of Technology, Poland

- ↑ Lecture Notes From the website of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

- ↑ The Early History of Catalysis A.J B. Robertson, Chemistry Department, Kings College, London.

- ↑ Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner's Feuerzeug George P. Kaufmann, Chemistry Department, California State University, Fresno, California (U.S. state).

- ↑ C. B. Désormes and N. Clément (1806), Annals Chim. 59 (329)

- ↑ H. Davy (1817), Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. 107 (77)

- ↑ J. W. Döbereiner (1823), Ann. Phys. 74 (269)

- ↑ J. W. Döbereiner (1823), Ann. Chim. 24 (91)

- ↑ J. J. Berzelius, Some Ideas on a New Force which Acts in Organic Compounds, Annales chimie physiques, 1836, vol. 61, 146–151. Translated in Henry M. Leicester and Herbert S. Klickstein, A Source Book in Chemistry 1400-1900 (1952), p. 267. Google books

- ↑ Keith J. Laidler and John H. Meiser (1982). Physical Chemistry, 1st Edition. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing, p.423. ISBN 0-8053-5682-7.

- ↑ W. Ostwald, Zeitschrift für physikalische Chemie, volume 15, pages 705-706 (1894)

- ↑ M.W. Roberts (2000). "Birth of the catalytic concept (1800-1900)". Catalysis Letters 67 (1): 1–4.

- ↑ What is Catalysis or Catalysis, So what? From the website of the North American Catalysis Society.