Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882 – April 12, 1945), often called FDR, was 32nd President of the United States of America from 1933 to 1945. He is best known for confronting the Great Depression of the 1930s with a series of activist federal programs called the "New Deal", for leading the Allies of World War II to victory over Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany, and for defining modern American liberalism and building a coalition of voters called the New Deal Coalition that proved dominated national and state elections 1932-48 and remained powerful into the 1960s. A central figure of the 20th century, Roosevelt has consistently been ranked as one of the three greatest presidents of all time by experts.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Roosevelt created the New Deal to provide relief for the unemployed, recovery for the economy, and reform of the economic system so it would never happen again. His most famous legacies still in operation are the Social Security system and the Securities and Exchange Commission (which regulates Wall Street).

His aggressive use of an active federal government, his powerful radio speeches, and his support for labor unions and big city machines re-energized the Democratic Party. The millions of new voters he attracted caused a realignment that formed the Fifth Party System. His legacy continued in the New Deal coalition. He and his highly visible wife Eleanor Roosevelt remain touchstones for modern American liberalism. The conservatives vehemently fought back, but Roosevelt consistently prevailed until he tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937. Thereafter, the new Conservative coalition successfully ended New Deal expansion, and during World War II closed the major relief programs like the WPA and Civilian Conservation Corps, arguing that unemployment had disappeared.

After 1938, Roosevelt championed re-armament and led the nation away from isolationism as the world headed into the war. He provided extensive support in terms of money and munition and ships (but not soldiers) to Winston Churchill and the British war effort before the attack on Pearl Harbor (Dec. 7, 1941) pulled the U.S. into the fighting. During the war, Roosevelt, working closely with his aide Harry Hopkins and his chief of staff, Fleet Admiral William Leahy, provided decisive leadership against Nazi Germany and made the United States the principal arms supplier and financier of the Allies. American forces played the major role in defeating Hitler in western Europe (as Stalin's Russia played the major role in the East). U.S. forces played the major role in defeating Japan in the Pacific, and gave strong support to the Nationalist government of China. Roosevelt pushed through a draft in 1940 and used executive orders to give African Americans access to high-paying war jobs. Roosevelt led the United States as it became the Arsenal of Democracy and put 16 million American men into uniform.

On the homefront his term saw the vast expansion of industry, the elimination of unemployment, restoration of prosperity, new taxes that affected all income groups, price controls and rationing, 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans sent to relocation camps, and new opportunities open for African Americans and women. As the Allies neared victory, Roosevelt played a critical role in shaping the post-war world, particularly through the Yalta Conference and the creation of the United Nations.

Roosevelt's administration redefined liberalism for subsequent generations and realigned the Democratic Party based on his New Deal coalition of labor unions, farmers, ethnic, religious and racial minorities, intellectuals, the South, big city machines, and the poor and workers on relief.

Personal life

Early life

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was born on January 30, 1882 in Hyde Park, in the Hudson Valley in upstate New York. His father, James Roosevelt, Sr., and his mother, Sara Ann Delano, were each from wealthy old New York families, of Dutch and French ancestry respectively. Franklin was their only child. Roosevelt grew up in an atmosphere of privilege. Sara was a possessive mother, while James was an elderly and remote father (he was 54 when Franklin was born). Sara was the dominant influence in Franklin's early years.[1] Frequent trips to Europe made Roosevelt conversant in German and French. He learned to ride, shoot, row, and play polo and lawn tennis.

Roosevelt went to Groton School, an Episcopal boarding school in Massachusetts. He was heavily influenced by the headmaster, Endicott Peabody, who preached the duty of Christians to help the less fortunate and urged his students to enter public service. Roosevelt completed his undergraduate studies at Harvard College, where he lived in luxurious Adams House. While at Harvard, he saw his distant cousin Theodore Roosevelt become president, and Theodore's vigorous leadership style and reforming zeal made him Franklin's role model and hero. In 1902, he met his future wife Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, Theodore's niece, at a White House reception. Eleanor and Franklin were fifth cousins, once removed.[2]

Franklin and Eleanor married in 1905.

Roosevelt entered Columbia University Law School in 1905, and, never took a degree because he had passed the New York State Bar exam. In 1908 he took a job with the prestigious Wall Street firm of Carter, Ledyard and Milburn, dealing mainly with corporate law.

Marriage and family life

Roosevelt married Eleanor over the resistance of his mother. They were married March 17, 1905, with Eleanor's uncle, President Theodore Roosevelt standing in for Eleanor's deceased father. The young couple moved into a house bought for them by Roosevelt's mother, who became a frequent house guest, much to Eleanor's chagrin. Roosevelt was a charismatic, handsome, and socially active man. In contrast, Eleanor was shy and disliked social life, and at first stayed at home to raise their children. They had six children in rapid succession:

- Anna Eleanor (1906–1975)

- James (1907–1991)

- Franklin Delano, Jr. (March 3–November 7, 1909)

- Elliott (1910–1990)

- a second Franklin Delano, Jr. (1914–1988)

- John Aspinwall (1916–1981)

The five surviving Roosevelt children all led tumultuous lives overshadowed by their famous parents. They had among them nineteen marriages, fifteen divorces and twenty-nine children. All four sons were officers in World War II and were decorated, on merit, for bravery. Their postwar careers, whether in business or politics, were disappointing. Two of them were elected to the U.S. House of Representatives (FDR, Jr. served three terms representing the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and James served six terms representing the 26th district in California) but none were elected to higher office despite several attempts.

Roosevelt found romantic outlets outside his marriage. One of these was with Eleanor's social secretary Lucy Mercer, with whom Roosevelt began an affair soon after she was hired in early 1914. In September 1918, Eleanor found letters in Franklin's luggage that revealed the affair. Eleanor confronted him with the letters and demanded a divorce. While the marriage survived, Eleanor established a separate house in Hyde Park at Valkill.

Early political career

State Senator

In 1910, Roosevelt ran for the New York State Senate from the district around Hyde Park, which had not elected a Democrat since 1884. The Roosevelt name, with its associated wealth, prestige and influence in the Hudson Valley, and the Democratic landslide that year carried him to the state capital of Albany, New York, where he became a leader of a group of reformers who opposed Manhattan's Tammany Hall machine which dominated the state Democratic Party. Roosevelt soon became a popular figure among New York Democrats.

Roosevelt served 1913-20 as Assistant Secretary of the Navy under Woodrow Wilson.

In 1914, he was defeated in the Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate by Tammany Hall-backed James W. Gerard. Roosevelt worked to expand the Navy and founded the United States Navy Reserve. Wilson sent the Navy and Marines to intervene in Central American and Caribbean countries. In his 1920 campaign for Vice President, Roosevelt claimed that he had played a significant role in Latin American politics and had even written the constitution which the U.S. imposed on Haiti in 1915.[3]

Roosevelt developed a life-long affection for the Navy. He showed great administrative talent and quickly learned to negotiate with Congressional leaders and other government departments to get budgets approved, and with officials like Joseph P. Kennedy at Navy yards and commercial shipyards to get the ships built. He became an enthusiastic advocate of the submarine and also of means to combat the German submarine menace to Allied shipping: he proposed building a mine barrier across the North Sea from Norway to Scotland. In 1918, he visited Britain and France to inspect American naval facilities; during this visit he met Winston Churchill for the first time. With the end of World War I in November 1918, he was in charge of demobilization, although he opposed plans to completely dismantle the Navy.

Campaign for Vice-President

The 1920 Democratic National Convention chose Roosevelt as the candidate for Vice President on the ticket headed by Governor James M. Cox of Ohio, helping build a national base. The Cox-Roosevelt ticket lost in a huge landslide to Republican Warren Harding. Roosevelt then retired to a New York City legal practice, but few doubted that he would soon run for public office again.

Paralytic illness

In August 1921, while the Roosevelts were vacationing at Campobello Island, New Brunswick, Roosevelt contracted an illness, at the time believed to be polio[4], which resulted in Roosevelt's total and permanent paralysis from the waist down. For the rest of his life, Roosevelt refused to accept that he was permanently paralyzed. He tried a wide range of therapies, including hydrotherapy, and, in 1926, he purchased a resort at Warm Springs, Georgia, where he founded a hydrotherapy center for the treatment of polio patients which still operates as the Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation. After he became President, he helped to found the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (now known as the "March of Dimes"). His leadership in this organization is one reason he is commemorated on the dime coin.

At a time, when media intrusion in the private lives of public figures was much less intense than it is today, Roosevelt was able to convince many people that he was in fact getting better, which he believed was essential if he was to run for public office again. Fitting his hips and legs with iron braces, he laboriously taught himself to walk a short distance by swiveling his torso while supporting himself with a cane. In private, he used a wheelchair, but he was careful never to be seen in it in public. He usually appeared in public standing upright, supported on one side by an aide or one of his sons.

Governor of New York, 1928-1932

By 1928, Roosevelt believed he had recovered sufficiently to resume his political career. He had been careful to maintain his contacts in the Democratic Party and had allied himself with Al Smith, the current governor and the Democratic presidential nominee in 1928.

To gain the Democratic nomination for the election, Roosevelt had to make his peace with the Tammany Hall machine, which he did with some reluctance. Roosevelt was elected Governor by a narrow margin, and came to office in 1929 as a reform Democrat. As Governor, he established a number of new social programs, and began gathering the team of advisors he would bring with him to Washington four years later, including Frances Perkins and Harry Hopkins.

The main weakness of Roosevelt's gubernatorial administration was the corruption of the Tammany Hall machine in New York City. Roosevelt had made his name as an opponent of Tammany, but needed the machine's goodwill to be re-elected in 1930. As the 1930 election approached, Roosevelt set up a judicial investigation into the corrupt sale of offices. In 1930, Roosevelt was elected to a second term by a margin of more than 700,000 votes, defeating Republican Charles H. Tuttle.

1932 presidential election

Roosevelt's strong base in the most populous state made him an obvious candidate for the Democratic nomination, which was hotly contested since it seemed clear that incumbent Herbert Hoover would be defeated at the 1932 election. Al Smith was supported by some city bosses, but had lost control of the New York Democratic party to Roosevelt. Roosevelt built his own national coalition with personal allies such as newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, Irish leader Joseph P. Kennedy, and California leader William G. McAdoo. When Texas leader John Nance Garner switched to FDR, he was given the vice presidential nomination.

The election campaign was conducted under the shadow of the Great Depression. During the campaign, Roosevelt said: "I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people", coining a slogan that was later adopted for his legislative program as well as his new coalition.

Economist Marriner Eccles observed that "given later developments, the campaign speeches often read like a giant misprint, in which Roosevelt and Hoover speak each other's lines."[5] Roosevelt denounced Hoover's failures to restore prosperity or even halt the downward slide, and he ridiculed Hoover's huge deficits. Roosevelt campaigned on an economy platform. On September 23, Roosevelt made the gloomy evaluation that, "Our industrial plant is built; the problem just now is whether under existing conditions it is not overbuilt. Our last frontier has long since been reached." Hoover damned that pessimism as a denial of "the promise of American life . . . the counsel of despair."[6] The prohibition issue solidified the wet vote for Roosevelt, who noted that repeal would bring in new tax revenues.

Roosevelt won 57% of the vote and carried all but six states. The anti-Smith rebellion in the South was over, and the region was "Solid South" again for the Democrats. Most of the new Catholic voters that Smith had mobilized in 1928 turned out again to vote Democratic. Labor unions were weak, but Roosevelt made gains in the previously Republican industrial belt.

After the election, Roosevelt refused Hoover's requests for a meeting to come up with a joint program to stop the downward spiral, claiming it would tie his hands. The economy spiralled downward until the banking system began a complete nationwide shutdown as Hoover's term ended. In February 1933, an assassin, fired five shots at Roosevelt, missing him but killing Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak; historians agree that FDR was the target, not the mayor.

First term, 1933-1937

- See also: New Deal

When Roosevelt was inaugurated in March 1933, the U.S. was at the nadir of the worst depression in its history. A quarter of the workforce was unemployed. Farmers were in deep trouble as prices fell by 60%. Industrial production had fallen by more than half since 1929. In a country with limited government social services outside the cities, two million were homeless. The banking system had collapsed completely. Beginning with his inauguration address, Roosevelt blamed the economic downturn on businessmen, the quest for profit, and the self-interest basis of capitalism:

Primarily this is because rulers of the exchange of mankind's goods have failed through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence, have admitted their failure, and have abdicated. Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men. True they have tried, but their efforts have been cast in the pattern of an outworn tradition. Faced by failure of credit they have proposed only the lending of more money. Stripped of the lure of profit by which to induce our people to follow their false leadership, they have resorted to exhortations, pleading tearfully for restored confidence. They know only the rules of a generation of self-seekers. They have no vision, and when there is no vision the people perish. The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.

Historians categorized Roosevelt's program as "relief, recovery and reform". Relief was urgently needed by tens of millions of unemployed. Recovery meant boosting the economy back to normal. Reform meant long-term fixes of what was wrong, especially with the financial and banking systems. Roosevelt's series of radio talks, known as fireside chats, presented his proposals directly to the American public.[7]

First New Deal, 1933-1934

Roosevelt's "First 100 Days" concentrated on the first part of his strategy: immediate relief. From March 9 to June 16, 1933, he sent Congress a record number of bills, all of which passed easily. To propose programs, Roosevelt relied on leading senators, especially George Norris, Robert F. Wagner and Hugo Black, as well as his own Brain Trust of academic advisers. Like Hoover, he saw the Depression as partly a matter of confidence, caused in part by people no longer spending or investing because they were afraid to do so. He therefore set out to restore confidence through a series of dramatic gestures.

FDR's natural air of confidence and optimism did much to reassure the nation. His inauguration on March 4, occurred in the middle of a bank panic, hence the backdrop for his famous words: "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself."[8] The very next day he announced a plan to allow banks to reopen, which they largely did by the end of the month. This was his first proposed step to recovery.

- Relief measures included the continuation of Hoover's major relief program for the unemployed under the new name, Federal Emergency Relief Administration. The most popular of all New Deal agencies, and Roosevelt's favorite, was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which hired 250,000 unemployed young men to work on rural local projects. Congress provided mortgage relief to millions of farmers and homeowners. Roosevelt expanded a Hoover agency, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, making it a major source of financing to railroads and industry. Roosevelt made agriculture relief a high priority and set up the first Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). The AAA tried to force higher prices for commodities by paying farmers to take land out of crops and to cut herds.

- Reform of the economy was the goal of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933. It tried to end cutthroat competition by forcing industries to come up with codes that established the rules of operation for all firms within specific industries, such as minimum prices, agreements not to compete, and production restrictions. Industry leaders negotiated the codes which were then approved by NIRA officials. Industry needed to raise wages as a condition for approval. Provisions encouraged unions and suspended anti-trust laws. The NIRA was found to be unconstitutional by unanimous decision of the Supreme Court on May 27, 1935. Roosevelt opposed the decision, but realized the NRA had failed and did not try to revive it. [9] In 1933, major new banking regulations were passed. In 1934, the Securities and Exchange Commission was created to regulate Wall Street, with 1932 campaign fundraiser Joseph P. Kennedy in charge.

- Recovery was pursued through "pump-priming" (that is, federal spending). The NIRA included $3.3 billion of spending through the Public Works Administration to stimulate the economy, which was to be handled by Interior Secretary Harold Ickes. Roosevelt worked with Republican Senator George Norris to create the largest government-owned industrial enterprise in American history, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which built dams and power stations, controlled floods, and modernized agriculture and home conditions in the poverty-stricken Tennessee Valley.

Roosevelt keot his campaign promise by cutting the regular federal budget, including 40% cuts to veterans' benefits and cuts in overall military spending. He removed 500,000 veterans and widows from the pension rolls and slashed benefits for the remainder. Protests erupted, led by the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Roosevelt held his ground, but when the angry veterans formed a coalition with Senator Huey Long and passed a huge bonus bill over his veto, he was defeated. He succeeded in cutting federal salaries and the military and naval budgets. He reduced spending on research and education—there was no New Deal for science until World War II began.

Roosevelt also kept his promise to push for repeal of Prohibition. In April 1933, he issued an Executive Order redefining 3.2% alcohol as the maximum allowed, thus allowing real beer; Congress and the states quickly the 21st Amendment ending prohibition.

Second New Deal, 1935-1936

After the 1934 Congressional elections, which gave Roosevelt large majorities in both houses, there was a fresh surge of legislation called the Second New Deal.. These measures included the Works Progress Administration (WPA) which set up a national relief agency that employed two million family heads. However, even at the height of WPA employment in 1938, unemployment was still 12.5% according to figures from Michael Darby.[10]The Social Security Act established Social Security and promised economic security for the elderly, the poor and the sick. Senator Wagner wrote the Wagner Act, which officially became the National Labor Relations Act. The act established the federal rights of workers to organize unions, to engage in collective bargaining, and to launch strikes.

While the First New Deal of 1933 had broad support from most sectors, the Second New Deal challenged the business community. Conservative Democrats, led by Al Smith, fought back with the American Liberty League, but it failed to mobilize much grass roots support. By contrast, the labor unions, energized by the Wagner Act, signed up millions of new members and became a major backer of Roosevelt's reelections in 1936, 1940 and 1944.[11]

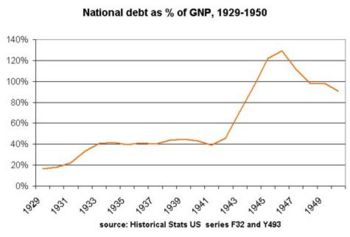

Economic challenges

Government spending increased from 8.0% of gross national product (GNP) under Hoover in 1932 to 10.2% of the GNP in 1936; the national debt, which doubled under Hoover from 18% to 40% of GNP, remained constant under FDR until the war came. [12]

Deficit spending had been recommended by some economists, most notably by British economist John Maynard Keynes, but Roosevelt ignored them. Some economists in retrospect have argued that the National Labor Relations Act and Agricultural Adjustment Administration were ineffective policies because they relied on price fixing.[13] The GNP was 34% higher in 1936 than in 1932 and 58% higher in 1940 on the eve of war. That is, the economy grew 58% from 1932 to 1940 in 8 years of peacetime, and then grew 56% from 1940 to 1945 in 5 years of wartime. Total employment during Roosevelt's term expanded by 18 million jobs, with an average annual increase in jobs during his administration of 5.3%. However, the economic recovery did not absorb all the unemployment Roosevelt inherited. In his first term, unemployment fell by two-thirds from 25% when he took office to 9.1% in 1937 but then stayed high until it vanished during the war.

During the war, the economy operated under such different conditions that comparison is impossible with peacetime. However, Roosevelt in his 1944 State of the Union Address, he advocated that Americans should think of basic economic rights as a "Second Bill of Rights".

Roosevelt made no significant changes to the income tax. In 1932, Hoover proposed and Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1932, increasing the top marginal tax rate on individual incomes from 25% to 63%, and enacted a wide range of additional excise taxes. In 1936, Congress added a higher top rate of 79% on individual income greater than $5 million, and that rate was increased again in 1939. Before the war only the richest 10% paid federal income taxes. During the war the base was expanded to 90% of Americans, and the top marginal tax rate was moved up to 91%, and federal taxes were withheld from paychecks (instead of being due in March the following year).

| Unemployment (% Labor Force) | ||

| Year | Lebergott | Darby[14] |

| 1933 | 24.9 | 20.6 |

| 1934 | 21.7 | 16.0 |

| 1935 | 20.1 | 14.2 |

| 1936 | 16.9 | 9.9 |

| 1937 | 14.3 | 9.1 |

| 1938 | 19.0 | 12.5 |

| 1939 | 17.2 | 11.3 |

| 1940 | 14.6 | 9.5 |

| 1941 | 9.9 | 8.0 |

| 1942 | 4.7 | 4.7 |

| 1943 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| 1944 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 1945 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

Foreign policy, 1933-36

The rejection of the League of Nations treaty in 1919 marked the dominance of isolationism from world organizations in American foreign policy. Despite Roosevelt's Wilsonian background, he and Secretary of State Cordell Hull acted with great care not to provoke isolationist sentiment. Roosevelt's "bombshell" message to the world monetary conference in 1933 effectively ended any major efforts by the world powers to collaborate on ending the worldwide depression, and allowed Roosevelt a free hand in economic policy.[15]

The main foreign policy initiative of Roosevelt's first term was the Good Neighbor Policy, which was a re-evaluation of U.S. policy towards Latin America. Since the Monroe Doctrine of 1823. American forces were withdrawn from Haiti, and new treaties with Cuba and Panama ended their status as protectorates. In December 1933, Roosevelt signed the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, renouncing the right to intervene unilaterally in the affairs of Latin American countries.[16]

Landslide re-election, 1936

In the 1936 presidential election, Roosevelt campaigned on his New Deal programs against Kansas Governor Alf Landon, who accepted much of the New Deal but objected that it was hostile to business and involved too much waste. Roosevelt and Garner won 61% of the vote and carried every state except Maine and Vermont. The New Deal Democrats won even larger majorities in Congress. Roosevelt was backed by a coalition of voters which included traditional Democrats across the country, small farmers, the "Solid South", Catholics, big city machines, labor unions, northern African Americans, Jews, intellectuals and political liberals. This "New Deal coalition" remained largely intact for the Democratic party until the 1960s.[17]

Second term, 1937-1941

In dramatic contrast to the first term, very little major legislation was passed in the second term. There was a United States Housing Authority (1937), a second Agricultural Adjustment Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which created the minimum wage. When the economy began to deteriorate again in late 1937, Roosevelt responded with an aggressive program of stimulation, asking Congress for $5 billion for WPA relief and public works. This managed to eventually create a peak of 3.3 million WPA jobs by 1938.

The Supreme Court was the main obstacle to Roosevelt's programs during his first term, overturning many of his programs. In particular in 1935 the Court unanimously ruled that the National Recovery Act (NRA) was an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the president. Roosevelt stunned Congress in early 1937 by proposing a law allowing him to appoint five new justices, a "persistent infusion of new blood". [18] This "court packing" plan ran into intense political opposition from his own party, led by Vice President Garner, since it seemed to upset the separation of powers and give the President control over the Court. Roosevelt's proposals were defeated. The Court also drew back from confrontation with the administration by finding the Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act to be constitutional. Deaths and retirements on the Supreme Court soon allowed Roosevelt to make his own appointments to the bench with little controversy. Between 1937 and 1941, he appointed eight liberal justices to the court.[19]

Roosevelt had massive support from the rapidly growing labor unions, but by 1936 they had split into bitterly feuding American Federation of Labor and Committee for Industrial Organization factions, the latter led by John L. Lewis.[20]

Determined to overcome the opposition of conservative Democrats in Congress (mostly from the South), Roosevelt involved himself in the 1938 Democratic primaries, actively campaigning for challengers who were more supportive of New Deal reform. His targets denounced Roosevelt for trying to take over the Democratic party and used the argument that they were independent to win reelection. Roosevelt failed badly, managing to defeat only one target, a conservative Democrat from New York City. [21]

In the November 1938 election, Democrats lost six Senate seats and 71 House seats. Losses were concentrated among pro-New Deal Democrats. When Congress reconvened in 1939, Republicans under Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft formed a Conservative coalition with Southern Democrats, virtually ending Roosevelt's ability to get his domestic proposals enacted into law. The minimum wage law of 1938 was the last substantial New Deal reform act passed by Congress. [22]

Foreign policy, 1937-1941

The rise to power of Adolf Hitler in Germany aroused fears of a new world war. In 1935, at the time of Italy's invasion of Ethiopia, Congress passed the Neutrality Act, applying a mandatory ban on the shipment of arms from the U.S. to any combatant nation. Roosevelt opposed the act on the grounds that it penalized the victims of aggression such as Ethiopia, and that it restricted his right as President to assist friendly countries, but public support was overwhelming so he signed it. In 1937, Congress passed an even more stringent act, but when the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, public opinion favored China, and Roosevelt found various ways to assist that nation.[23]

Prior to 1933, Roosevelt harbored considerable dislike for Adolf Hitler and considered him dangerous. In October 1937, he gave the "Quarantine Speech" aiming to contain aggressor nations. He proposed that warmongering states be treated as a public health menace and be "quarantined." [24]Meanwhile he secretly stepped up a program to build long range submarines that could blockade Japan. In the summer of 1938, sensing war would come, Roosevelt began preparations for hemispheric defense and arms production; he asked for far more airplanes than the Air Corps had envisioned. When World War II broke out in 1939, Roosevelt rejected the Wilsonian neutrality stance and sought ways to assist Britain and France militarily.

Roosevelt turned to Harry Hopkins for foreign policy advice; Hopkins became his chief wartime advisor. They sought innovative ways to help Britain, whose financial resources were exhausted by the end of 1940. Congress, where isolationist sentiment was in retreat, passed the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941, allowing the U.S. to "lend" huge amounts of military equipment in return for "leases" on British naval bases in the Western Hemisphere. In sharp contrast to the loans of World War I, there would be no repayment after the war. Roosevelt was a lifelong free trader and anti-imperialist, and ending European colonialism was one of his objectives. Roosevelt forged a close personal relationship with Churchill, who became Prime Minister of Britain in May 1940.

In May 1940, a stunning German blitzkrieg overran Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and finally France, leaving Britain vulnerable to invasion. Roosevelt, who was determined to defend Britain, took advantage of the rapid shifts of public opinion. A consensus was clear that military spending had to be dramatically expanded. There was no consensus on how much the U.S. should risk war in helping Britain. FDR replaced his cautious war and navy secretaries with pro-war interventionist Republican leaders, Henry L. Stimson and Frank Knox, as Secretaries of War and the Navy respectively. The fall of Paris shocked American opinion, and isolationist sentiment declined. Both parties gave support to his plans to rapidly build up the American military, but the isolationists warned that Roosevelt would get the nation into an unnecessary war with Germany. He successfully urged Congress to enact the first peacetime draft in American history in 1940 (it was renewed in 1941 by one vote in Congress). Roosevelt was supported by the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, and opposed by the isolationist America First Committee.

Roosevelt used his personal charisma to build support for intervention. America should be the "Arsenal of Democracy," he told his fireside audience. In August, Roosevelt's "Destroyers for Bases Agreement" traded 50 old American destroyers to Britain in exchange for base rights in the British Atlantic islands. This was a precursor of the March 1941 "Lend-Lease" agreement which began to direct massive military and economic aid to Britain, the China and the Soviet Union.

After reelection in 1940, with much of Europe under German domination, Roosevelt cautiously prepared for war by extending the Atlantic neutrality zone, pushing the Lend-Lease Act through Congress, and drawing plans for an enlarged army. Roosevelt used the German submarine attacks on the American destroyer "Greer" on 4 September 1941 and the U-boat torpedoing of the destroyer "Kearny" on 16-17 October 1941 as pretexts to extend naval warfare in the Atlantic without congressional approval or the repeal of neutrality legislation. Through the fall of 1941, Roosevelt continued to plan and assemble the necessary military force to combat Hitler, although he never terminated diplomatic relations with Germany and never intended to appeal to Congress for a declaration of war. While there may have been miscalculations, Roosevelt did not provoke the attack on Pearl Harbor as a means of getting into war with Germany.[25]

Third term, 1941-1945

The two-term tradition had been an unwritten rule since George Washington declined to run for a third term in 1796, but Roosevelt, after blocking the presidential ambitions of cabinet members James Farley and Cordell Hull, decided to run for a third term. In his campaign against Republican Wendell Willkie, Roosevelt stressed both his proven leadership experience and his intention to do everything possible to keep the United States out of war. Roosevelt won the 1940 election with 55% of the popular vote and 38 of the 48 states. A shift to the left within the Administration was shown by the naming of Henry A. Wallace as Vice President in place of Garner, who had become a bitter enemy of Roosevelt after 1937.

Roosevelt's third term was dominated by World War II, in Europe and in the Pacific. Roosevelt slowly began re-armament in 1938 since he was facing strong isolationist sentiment from leaders like Senators William Borah and Robert Taft who supported re-armament. By 1940, it was in high gear, with bipartisan support, partly to expand and re-equip the Army and Navy and partly to become the "Arsenal of Democracy" supporting Britain, France, China and (after June 1941), the Soviet Union. As Roosevelt took a firmer stance against the Axis Powers, American isolationists—including Charles Lindbergh and America First—attacked the President as an irresponsible warmonger. Unfazed by these criticisms and confident in the wisdom of his foreign policy initiatives, FDR continued his twin policies of preparedness and aid to the Allied coalition. On December 29, 1940, he delivered his Arsenal of Democracy fireside chat, in which he made the case for involvement directly to the American people, and a week later he delivered his famous Four Freedoms speech in January 1941, further laying out the case for an American defense of basic rights throughout the world.

The military buildup caused nationwide prosperity. By 1941, unemployment had fallen to under 1 million. There was a growing labor shortage in all the nation's major manufacturing centers, accelerating the "Great Migration" of African-American farmers from the Southern states, and of underemployed farmers and workers from all rural areas and small towns. The homefront was subject to dynamic social changes throughout the war, though domestic issues were no longer Roosevelt's most urgent policy concerns.

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Roosevelt extended Lend-Lease to the Soviets. During 1941, Roosevelt also agreed that the U.S. Navy would escort British convoys as far east as Britain and would fire upon German ships or submarines if they attacked Allied shipping within the U.S. Navy zone. Moreover, by 1941, U.S. Navy aircraft carriers were secretly ferrying British fighter planes between Britain and the Mediterranean war zones, and the British Royal Navy was receiving supply and repair assistance at American naval bases.

Thus, by mid-1941, Roosevelt had committed the U.S. to the Allied side with a policy of "all aid short of war." Roosevelt met with Churchill in August 1941, to write the Atlantic Charter in what was to be the first of several wartime conferences. The War Department's "Victory Program," provided the President with the estimates necessary for the total mobilization of manpower, industry, and logistics to defeat Germany and Japan.[26] The program also planned to dramatically increase aid to the Allied nations and to have ten million men in arms, half of whom would be ready for deployment abroad in 1943. Roosevelt was firmly committed to the Allied cause but his war plans were published by the isolationist Chicago Tribune days before Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.[27]

Pearl Harbor

Roosevelt's goals in the Pacific were to aid China against Japanese aggression and to deter Japan from attacking the Soviets through Siberia. After Japan occupied northern French Indo-China in late 1940, he authorized increased aid to the China. In July 1941, after Japan occupied the remainder of Indo-China, the U.S. cut off the sales of oil.[28] Japan thus lost more than 90% of its oil supply and had to rely on stockpiles. Roosevelt continued negotiations with the Japanese government in the hope of averting war. Meanwhile he started shifting the long-range B-17 bomber force to the Philippines, where it could threaten the fire-bombing of Japanese cities.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor, destroying or damaging all the battleships and killing more than 2,400 Americans. Antiwar sentiment in the United States evaporated overnight and the country united behind Roosevelt. The Japanese moved quickly to occupy the Philippines and the British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia, taking Singapore in February 1942 and advancing through Burma to the borders of British India by May, cutting off the overland supply route to China.

Despite the wave of anger that swept across the U.S. in the wake of Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt decided from the start that the defeat of Nazi Germany had to take priority. On December 11, 1941, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States and the U.S. declared war on them. Churchill came to Washington in late December and planned a broad informal alliance between the U.S., Britain, China and the Soviet Union, with the objectives of halting the German advances in Russia and in North Africa; bombarding Germany with strategic air power; eventually launching an invasion of western Europe with the aim of crushing Nazi Germany between two fronts; and saving China and defeating Japan.

War strategy

The "Big Three" (Roosevelt, Churchill, and Joseph Stalin), together with Chiang Kai-shek, oversaw an alliance in which British, American and Allied concentrated in the West, Russian troops fought on the Eastern front, and Chinese, British and American troops fought Japan. The Allies formulated strategy in a series of high profile conferences as well as contact through diplomatic and military channels. Roosevelt guaranteed that the U.S. would be the "Arsenal of Democracy" by shipping $50 billion of Lend Lease supplies, primarily to Britain and also to the USSR, China and other Allies.

The Pentagon (that is the Joint Chiefs of Staff) took the view that the quickest way to defeat Germany was to open a western front in France across the English Channel. Churchill, wary of the casualties he feared this would entail, favored a more indirect approach, advancing northwards from the Mediterranean Sea. Roosevelt rejected this plan. Stalin advocated opening a Western front at the earliest possible time, as the bulk of the land fighting in 1942-44 was on Soviet soil.

The Allies undertook the invasions of French Morocco and Algeria (Operation Torch) in November 1942, of Sicily (Operation Husky) in July 1943, and of Italy (Operation Avalanche) in September 1943. The strategic bombing campaign was escalated in 1944, pulverizing all major German cities and cutting off oil supplies. Strategic bombing was a 50-50 British-American operation. Roosevelt picked Dwight D. Eisenhower, and not George Marshall, to head the Allied cross-channel invasion, Operation Overlord that began on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Some of the most costly battle of the war ensued after the invasion, and the Allies were blocked on the German border in the "Battle of the Bulge" in December 1944; when Roosevelt died Allied forces were closing in on Berlin.

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, the Japanese advance reached its maximum extent by June 1942, when the U.S. Navy scored a decisive victory at the Battle of Midway. American (and Australian) forces then began a slow and costly progress through the Pacific islands, with the objective of gaining bases from which strategic air power could be brought to bear on Japan and from which Japan could ultimately be invaded. Roosevelt gave way in part to insistent demands from the public and Congress that more effort be devoted against Japan; he always insisted on Germany first.

Post-war planning

By late 1943, it was apparent that the Allies would ultimately defeat Nazi Germany, and it became increasingly important to make high-level political decisions about the course of the war and the postwar future of Europe. Roosevelt met with Churchill and Chiang Kai-shek at the Cairo Conference in November 1943, and then went to Persia (Iran) to confer with Churchill and Stalin. At the Tehran Conference, Roosevelt and Churchill told Stalin about the plan to invade France in 1944, and Roosevelt also discussed his plans for a postwar international organization. For his part, Stalin insisted on the redrawing of the eastern frontier of Poland along the so-called Curzon line, to reunited eastern and western Ukraine. Stalin was evidently pleased that the western Allies had abandoned any idea of moving into the Balkans or central Europe via Italy, and he went along with Roosevelt's plan for the United Nations. He also agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan when Germany was defeated.

By the beginning of 1945, however, with the Allied armies advancing into Germany and the Soviets in control of Poland, the issues had to come out into the open. In February, Roosevelt, despite his steadily deteriorating health, traveled to Yalta, in the Soviet Crimea, to meet again with Stalin and Churchill at the Yalta Conference. The Soviet Union was soon to occupy all of eastern Europe, and there was little Roosevelt and Churchill could do to prevent Stalin from taking permanent control.

Fourth term, 1945

Although Roosevelt was only 62 in 1944, his health had been in decline since at least 1940. The strain of his paralysis and the physical exertion needed to compensate for it for over 20 years had taken their toll, as had many years of stress and a lifetime of chain-smoking. He had been diagnosed with high blood pressure and long-term heart disease and was advised to modify his diet (although not to stop smoking). Aware of the risk that Roosevelt would die during his fourth term, the party regulars insisted that Henry A. Wallace, who was seen as too pro-Soviet, be dropped as Vice President. After considering James F. Byrnes of South Carolina and being turned down by Indiana Governor Henry F. Schricker, Roosevelt replaced Wallace with the little known Senator Harry S. Truman. In the 1944 election, Roosevelt and Truman won 53% of the vote and carried 36 states, against New York Governor Thomas Dewey.

After the Yalta conference in February 1945, relations between the western Allies and Stalin deteriorated rapidly, and so did Roosevelt's health. When he addressed Congress on his return from Yalta, many were shocked to see how old, thin and sick he looked. He spoke while seated in the well of the House, an unprecedented concession to his physical incapacity. But mentally he was still in full command. "The Crimean Conference," he said firmly, "ought to spell the end of a system of unilateral action, the exclusive alliances, the spheres of influence, the balances of power, and all the other expedients that have been tried for centuries — and have always failed. We propose to substitute for all these, a universal organization in which all peace-loving nations will finally have a chance to join."[29]

During March and early April 1945, he sent strongly worded messages to Stalin accusing him of breaking his Yalta commitments over Poland, Germany, prisoners of war and other issues. When Stalin accused the western Allies of plotting a separate peace with Hitler behind his back, Roosevelt replied: "I cannot avoid a feeling of bitter resentment towards your informers, whoever they are, for such vile misrepresentations of my actions or those of my trusted subordinates."[30]

Death

On March 30, 1945, Roosevelt went to Warm Springs to rest before his anticipated appearance at the founding conference of the United Nations. On April 12 he suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage and died. Lucy Mercer, his former mistress, was with him at the time of his death. In his latter years at the White House, Roosevelt was increasingly overworked and his daughter Anna Roosevelt Boettiger had moved in to provide her father companionship and support. Anna had also arranged for her father to meet with the now widowed Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd.

Roosevelt's death was met with shock and grief across the U.S. and around the world. At a time when the press did not pry into the health or private lives of presidents, his declining health had not been known to the general public. Roosevelt had been President for more than 12 years, longer than any other person, and had led the country through some of its greatest crises to the impending defeat of Nazi Germany and to within sight of the defeat of Japan as well.

Less than a month later, on May 8, came the moment Roosevelt fought for: V-E Day. President Harry Truman dedicated V-E Day and its celebrations to Roosevelt's memory, paying tribute to his commitment towards ending the war in Europe.

Civil rights issues

Roosevelt's record on civil rights has been the subject of much controversy. He was a hero to large minority groups, especially African-Americans, Catholics and Jews. African-Americans and Native Americans fared well in the New Deal relief programs, although they were not allowed to hold significant leadership roles in the WPA and CCC. Roosevelt needed the support of Southern Democrats for his New Deal programs, and therefore decided not to push for anti-lynching legislation that might threaten his ability to pass his highest priority programs. Roosevelt was highly successful in attracting large majorities of African-Americans, Jews and Catholics into his New Deal Coalition. Beginning in 1941 Roosevelt issued a series of FEPC executive orders designed to guarantee racial, religious and ethnic minorities a fair share of the new wartime jobs. He pushed for admission of African-Americans into better positions in the military. In 1942 Roosevelt made the final decision in ordering the internment of Japanese citizens (including the American-citizen children) and other enemy aliens. Beginning in the 1960s he was charged[31] with not acting decisively enough to prevent or stop the Holocaust which killed 6 million Jews. Critics cite episodes such as when in 1939, the 950 Jewish refugees on board the SS St. Louis were denied asylum and U.S. laws did not allow them entry.

Legacy

A 1999 survey of academic historians by CSPAN found that historians consider Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and Roosevelt the three greatest presidents by a wide margin, and other surveys are consistent.[32] Roosevelt is the sixth most admired person in the 20th century, according to Gallup.[33]

Both during and after his terms, critics of Roosevelt from left and right attacked his policies. The right said he went to far, the lefdt said he missed the opportunity to go much further. The rapid creation of new government programs that occurred during Roosevelt's term redefined the role of the government in the United States, and Roosevelt's advocacy of government social programs was instrumental in redefining liberalism for coming generations.[34] Roosevelt's energy, enthusiasm for government intervention, support for the little man and labor unions, encouragement of African Americans, and distrust of big business, and new directions continue to shape liberalism.

Conservatives salute Roosevelt for firmly establishing American leadership on the world stage, with the destruction of Nazism and Japanese militarism his highest priority.

His widow Eleanor Roosevelt continued to be a forceful presence in U.S. and world politics. Many members of his administration played leading roles in the administrations of Truman, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson, each of whom embraced Roosevelt's political legacy.[35]

Roosevelt's home in Hyde Park is now a National historic site and home to his Presidential library. His "Little White House" at Warm Springs, Georgia is a museum operated by the state of Georgia. The Roosevelt memorial has been established in Washington, D.C. next to the Jefferson Memorial on the Tidal Basin, and his image appears on the Roosevelt dime. Many parks, schools, roads, an aircraft carrier. along with sites in Europe, Twelve days after his death in 1945, Thomas Jefferson College in Chicago was renamed Roosevelt University.

Further reading

see the detailed guide at Franklin D. Roosevelt/Bibliography

- Alter, Jonathan. The Defining Moment: FDR's Hundred Days and the Triumph of Hope (2006), popular excerpt and text search

- Beschloss, Michael R. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941-1945 (2002). excerpt and text search

- Black, Conrad. Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom (2003). popular excerpt and text search

- Burns, James MacGregor. vol 1: Roosevelt" The Lion and the Fox (1956); excerpt and text search vol 1; vol. 2: Roosevelt: Soldier of Freedom 1940-1945 (1970), excerpt and text search vol 2; major interpretive scholarly biography, emphasis on politics; vol 2 is on war years and is online at ACLS e-books

- Dallek, Robert. Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932-1945 (2nd ed. 1995) scholarly survey of foreign policy excerpt and text search

- Freidel, Frank. Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Rendezvous with Destiny (1990), One-volume scholarly biography; covers entire life excerpt and text search 2006 reprint edition

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II (1995), joint biography by scholar excerpt and text search

- Graham, Otis L. and Meghan Robinson Wander, eds. Franklin D. Roosevelt: His Life and Times. (1985). encyclopedia by scholars

- Jenkins, Roy. Franklin Delano Roosevelt (2003) short popular bio from British perspective

- Kennedy, David M. Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. (1999), wide-ranging survey of national affairs by scholar online edition

- Larrabee, Eric. Commander in Chief: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, His Lieutenants, and Their War. History of how FDR handled the war excerpt and text search

- Leuchtenberg, William E. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940. (1963). Remains the standard scholarly interpretive history of era. excerpt and text search

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr., The Age of Roosevelt, 3 vols, (1957-1960), the classic narrative history. Strongly supports FDR.

- Smith, Jean Edward. FDR, (2007) 858pp. Most recent scholarly bio.

notes

- ↑ Eleanor and Franklin, Lash (1971), 111 et seq.

- ↑ They were both descended from Claes Martensz van Rosenvelt who arrived in New Amsterdam (Manhattan) from the Netherlands in the 1640s. Roosevelt's two grandsons, Johannes and Jacobus, began the Oyster Bay (Theodore Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt) and Hyde Park (FDR) branches of the Roosevelt family. Eleanor was descended from the Johannes branch, while FDR was descended from the Jacobus branch. See [1]

- ↑ Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., The Crisis of the Old Order, 364; Roosevelt's actual role is unclear but his claims was at best an overstatement and caused some controversy in the campaign.

- ↑ It has been recently speculated that his condition was actually Guillain–Barré syndrome [2]

- ↑ Kennedy, 102.

- ↑ More, The Politics of Economic Growth in Postwar America, (2002) p. 5.

- ↑ Leuchtenburg, (1963) ch 1, 2

- ↑ See the text of the address at Wikisource.[3].

- ↑ Ellis Hawley, The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly (1966) p. 124

- ↑ Michael R. Darby, "Three and a half million U.S. Employees have been mislaid: or, an Explanation of Unemployment, 1934-1941." Journal of Political Economy 84, no. 1 (1976): 1-16.

- ↑ Leuchtenberg 1963

- ↑ Historical Statistics (1976) series Y457, Y493, F32. The increase in debt during the depression and World War II are shown on the chart below.

- ↑ Parker.

- ↑ Derby counts WPA workers as employed; Lebergott as unemployed source: Historical Statistics US (1976) series D-86; Smiley 1983 Smiley, Gene, "Recent Unemployment Rate Estimates for the 1920s and 1930s," Journal of Economic History, June 1983, 43, 487-93.

- ↑ Leuchtenberg (1963) pp 199-203.

- ↑ Leuchtenberg (1963) pp 203-210.

- ↑ Leuchtenberg (1963) pp 183-196.

- ↑ Pusey, Merlo J. F.D.R. vs. the Supreme Court, American Heritage Magazine, April 1958, Volume 9, Issue 3

- ↑ Leuchtenberg (1963) pp 231-39

- ↑ Leuchtenberg (1963) pp 239-43.

- ↑ Leuchtenberg (1963)

- ↑ Leuchtenberg (1963) ch 11.

- ↑ Leuchtenberg (1963) ch 12.

- ↑ See [4] for text

- ↑ Freidel

- ↑ Mark Skinner Watson, Chief of Staff: Prewar Plans and Preparations, (1950), 331-366 online at [5]

- ↑ The Tribune later revealed the top secret that the Navy had cracked the Japanese code, but Tokyo did not get the news. Roosevelt did not prosecute because that would alert Tokyo. Dina Goren, "Communication Intelligence and the Freedom of the Press. The Chicago Tribune's Battle of Midway Dispatch and the Breaking of the Japanese Naval Code," Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Oct., 1981), pp. 663-690 online at JSTOR

- ↑ Historians are unsure whether Roosevelt intended to cut off all oil supplies, or whether Dean Acheson and other subordinates made the decision to do so. Irvine H. Anderson, Jr. "The 1941 De Facto Embargo on Oil to Japan: A Bureaucratic Reflexm" The Pacific Historical Review Vol. 44, No. 2 (May, 1975), pp. 201-231 at JSTOR

- ↑ Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932-1945, Robert Dallek (1995) at 520.

- ↑ War in Italy 1943-1945, Richard Lamb (1996) at 287.

- ↑ In works such as Arthur Morse's While Six Million Died: A Chronicle of American Apathy (New York, 1968), David S. Wyman's Paper Walls: America and the Refugee Crisis, 1938-1941 (Boston, 1968), and Henry L. Feingold's The Politics of Rescue: The Roosevelt Administration and the Holocaust, 1938-1945 (New Brunswick, NJ, 1970).

- ↑ American PresidentsSee, also, for example:

- Opinion Journal

- Gvsu.edu, website of Grand Valley State University

- The Washington Post found Washington, Lincoln, and Roosevelt to be the only "great" presidents.

- ↑ Leuchtenburg, William E. The FDR Years: On Roosevelt and His Legacy, Chapter 1, Columbia University Press, 1997.

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur Jr, Liberalism in America: A Note for Europeans from The Politics of Hope, 1962.

- ↑ William E Leuchtenburg, In the Shadow of FDR: From Harry Truman to George W. Bush (2001).