World War II, Homefront, U.S.: Difference between revisions

imported>Derek Hodges No edit summary |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{TOC|right}} | |||

The '''United States home front during World War II''' covers all the developments inside the United States, 1940-1945. For comparisons with other nations see [[World War II, Homefront]] | The '''United States home front during World War II''' covers all the developments inside the United States, 1940-1945. For comparisons with other nations see [[World War II, Homefront]] | ||

Revision as of 21:05, 25 June 2009

The United States home front during World War II covers all the developments inside the United States, 1940-1945. For comparisons with other nations see World War II, Homefront

Economic mobilization

Financier Bernard Baruch argued that in modern war there was little room for free enterprise. He said Washington must control all aspects of the economy and that both business and unions must be subservient to the nation's security interest. Furthermore, price controls were essential to prevent inflation and to maximize military power per dollar. He wanted labor to be organized to facilitate optimum production. Baruch believed labor should be cajoled, coerced, and controlled as necessary: a central government agency would orchestrate the allocation of labor. He supported what was known as a "work or fight" bill. Baruch advocated the creation of a permanent superagency similar to his old Industries Board. Thus Baruch proposed to freeze economic freedom during war in order to preserve it for peace. His approach enhanced the role of civilian businessmen and industrialists in determining what was needed and who would produce it.[1] Baruch's ideas were largely adopted, with James Byrnes appointed to carry them out.

Baruch was a consultant on economic matters and proposed or supported a number of measures including a pay-as-you-go tax plan as proposed by Beardsley Ruml and worked out by Milton Friedman.

Baruch proposed to stockpile rubber and tin; and started an emergency synthetic rubber program to replace natural rubber, the sources of which were under Japanese control. To conserve rubber, gasoline was rationed (because that was easier than rationing tires.)

Munitions

The mobilization of industry was guided by the rhetoric of mass production, yet most aircraft factories traditionally relied on more traditional hand-crafted processes that allowed for quick production acceleration and frequent design changes, but required highly skilled workers who produced a limited output. To build a thousand planes a day entirely new methods were needed, with gigantic factories and a large, much less skilled workforce (many of whom were women). Mass production was implemented by Henry Ford and his B-24 bomber plant, yet Grumman and General Motors' Eastern Aircraft, while largely shunned Detroit-style production methods nevertheless manufactured the bulk of the US Navy's carrier aircraft. (Ferguson, 2005)

Civilian consumption and rationing

| 1937 | 1939 | 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | 100 | 107 | 109 | 111 | 108 | 99 | 93 | 78 |

| Germany | 100 | 108 | 117 | 108 | 105 | 95 | 94 | 85 |

| USA | 100 | 96 | 103 | 108 | 116 | 115 | 118 | 122 |

| Source: Jerome B Cohen, Japan's Economy in War and Reconstruction (1949) p 354 | ||||||||

Civilian consumption increased 22% during the war, though there were many shortages in critical areas. Production stopped on many civilian items, such as automobiles, new houses, and new appliances. Many commodities, such as meat, sugar, butter, coffee, gasoline, tires, shoes and clothing were rationed. Local schools set up stations where people could get their ration coupons (with teachers handling the paperwork.) Each person (regardless of age) received the same food and clothing coupons. To purchase an item three things were needed: the storekeeper had to have the item in the first place, the purchaser had to have the cash, and had to have the coupons. Most automobile drivers received coupons for 3 gallons a week; those who could document special needs received extra gasoline coupons. (There was plenty of gasoline; the rationing was an efficient way to ration automobile tires, with rubber in very short supply.) Bread, milk and beer were not rationed. People eating in restaurants had to pay with cash and ration coupons. Rationing was generally supported by the civilian population, although there was some black market activity, that is, purchase of an item without the coupons. The government hunted down and prosecuted black marketeers. There was much "gray market" activity--that is family and neighbors selling or trading ration coupons; that was technically illegal but rarely prosecuted.

The main result was a striking egalitarianism of consumption, especially regarding food. Rationing was needed due to the needs of the men and women serving overseas. The commodities mentioned above were a very important key to the success of the US war effort. Also, rationing was also needed due to the limited shipping capabilities during the war. Many cargo ships were converted from public use to military use to aid in the war effort.

Bentley (1998) argues that wartime food rationing encouraged planners, consumers, and producers alike to focus on the communitarian dimensions of the American war effort. Rationing drew women into the national wartime effort, but the result was "simultaneously to elevate women's status and to maintain gender hierarchies." The Office of Price Administration instituted food rationing to combat high inflation while ensuring equitable distribution of scarce resources; from the start, it saw women as essential collaborators in a new, and democratic, practice. Rationing mobilized women as "wartime homemakers," especially as consumers who faced the challenge of providing meals while restricting sugar and meat consumption. (Ironically, although women worked in them, too, victory gardens and food production were more often viewed as men's work.) Women's work as food preparers also held the power to remind Americans daily of what the nation was collectively fighting for ("Freedom from want").

Conversion to war effort

The War and Navy departments purchased vast quantities of supplies; together with other war agencies they accounted for 40% of GNP by 1944. Automobile plants ceased production of passenger cars, creating a shortage of them in the consumer market. Wartime efforts were focused on aircraft engines, army trucks and tanks. Industrial production of wartime needs was established more quickly than any time before in history, however in many plants, periodic shortages of parts would bring the assembly lines to a halt, then require overtime from the employees (to meet quotas) when the parts arrived.[2]

The War Production Board (WPB) was established in 1942 by executive order of Franklin D. Roosevelt. The purpose of the board was to regulate the production and allocation of materials and fuel during World War II in the United States. It rationed such things as gasoline, heating oil, metals, rubber, and plastics. It was dissolved shortly after the defeat of Japan in 1945.

Taxes and controls

Federal tax policy was highly contentious during the war, with a liberal Roosevelt battling a conservative Congress. Everyone agreed on the need for high taxes to pay for the war. Roosevelt tried to impose a 100% tax on incomes over $25,000 (which failed to pass), while Congress enlarged the base downward. By 1944 nearly every employed person was paying federal income taxes (compared to 10% in 1940).

Many controls were put on the economy. The most important were price controls, imposed on most products, and monitored by the OPA. Wages were also controlled. In addition the military, which purchased upwards of 40% of the GNP, imposed priorities that largely shaped industrial production.[3]

Labor

The unemployment problem ended in the United States with the beginning of World War II, as stepped up wartime production created millions of new jobs, and the draft pulled young men out.[4]

In the United States, women also joined the workforce to replace men who had joined the forces, though in fewer numbers. Franklin D. Roosevelt stated that the efforts of civilians at home to support the war through personal sacrifice was as critical to winning the war as the efforts of the soldiers themselves. "Rosie the Riveter" became the symbol of women laboring in manufacturing. The war effort brought about significant changes in the role of women in society as a whole. Upon the end of the war, many of the munitions factories simply closed. Other women were replaced by returning veterans. However most women who wanted to continue working did so.

Labor shortages were felt in agriculture, even though most farmers were given an occupational exemption and few were drafted. Beekeepers also gained exemptions and favored treatment, because beeswax was considered a critical wartime need for rustproof coatings on vehicles and weapons going abroad. However large numbers of farm hands and rural residents volunteered for military service or moved to cities for factory jobs. At the same time many agricultural commodities were more needed for the military and for the civilian populations of allies. In some areas schools were temporarily closed at harvest time to enable students to work. Several hundred thousand enemy prisoners of war were used as farm laborers.

Labor Unions

The war mobilization also changed the CIO's relationship with both employers and the national government; much less is known about the rival AFL during the war.[5]

Nearly all the unions that belonged to the CIO were fully supportive of both the war effort and of the Roosevelt administration. However the coal miners led by John L Lewis, who had taken an isolationist stand in the years leading up to the war in a show of solidarity with the Soviet Union. Because Roosevelt was helping to defeat Germany, and Germany was allied to Russia, the left wing unionists tried to slow down the war effort through strikes in 1940-41. As soon as Russia was attacked by Germany they changed positions and became all-out supporters of the war. Indeed the leftists tried to stop rank-and-file members from striking for higher wages because that would slow the flow of war material to Russia. The CIO supported a wartime no-strike pledge that aimed to eliminate not only major strikes for new contracts, but also the innumerable small strikes called by shop stewards and local union leadership to protest particular grievances.

The CIO did not, on the other hand, strike over wages during the war. In return for labor's no-strike pledge, the government offered arbitration to determine the wages and other terms of new contracts. Wages went up, and so did prices. The union members made very high incomes thanks to overtime (paid at 150%), and rapid promotions to higher-paid positions, as well as jobs for all family members who wanted one.

The CIO unions grew much larger and stronger during the war. The government put pressure on employers to recognize unions to avoid the sort of turbulent struggles over union recognition of the 1930s, while unions were generally able to obtain maintenance of membership clauses, a form of union security, through arbitration and negotiation. Workers also won benefits, such as vacation pay, that had been available only to a few in the past while wage gaps between higher skilled and less skilled workers narrowed.

The experience of bargaining on a national basis, while restraining local unions from striking, also tended to accelerate the trend toward bureaucracy within the larger CIO unions. Some, such as the Steelworkers, had always been centralized organizations in which authority for major decisions resided at the top. The UAW, by contrast, had always been a more grassroots organization, but it also started to try to rein in its maverick local leadership during these years.

The CIO also had to confront deep racial divides in its own membership, particularly in the UAW plants in Detroit, where white workers sometimes struck to protest the promotion of black workers to production jobs, but also in shipyards in Alabama, mass transit in Philadelphia, and steel plants in Baltimore. The CIO leadership, particularly those in further left unions such as the Packinghouse Workers, the UAW, the NMU and the Transport Workers, undertook serious efforts to suppress hate strikes, to educate their membership and to support the Roosevelt Administration's tentative efforts to remedy racial discrimination in war industries through the Fair Employment Practices Commission. Those unions contrasted their relatively bold attack on the problem with the timidity and racism of the AFL.

The CIO unions were progressive in dealing with gender discrimination in wartime industry, which now employed many more women workers in nontraditional jobs. Unions that had represented large numbers of women workers before the war, such as the UE and the Food and Tobacco Workers, had fairly good records of fighting discrimination against women. Most union leaders saw women as temporary wartime replacements for the men in the armed forces. It was important that the wages of these women be kept high so that the veterans would get high wages.

Civilian support for war effort

A major government policy was to create official-sounding roles for civilians so they could have a sense of participation in the war. This was especially important for middle class citizens who did not work in munitions industries. Most of the "jobs" were artificial--such as hundreds of spotters in Illinois looking for enemy aircraft (which presumaby had been missed by the hundreds of spotters in Indiana and points East. In any case the government knew full well that no German planes had the range to approach the U.S. coastline.) The Civil Air Patrol was established, which enrolled civilian spotters in reconnaissance. Towers were built in coastal and border towns, and spotters were trained to recognize enemy aircraft, so as to report if any were seen. Blackouts were practiced in every city, even those far from the coast. All lighting had to be extinguished to avoid helping the enemy in targeting at night. The main purpose was to remind people that there was a war on and to provide activities that would engage the civil spirit of millions of people not otherwise involved in the war effort. In large part, this effort was successful, sometimes almost to a fault, such as the Plains states where many dedicated aircraft spotters took up their posts night after night watching the skies in an area of the country that no enemy aircraft of that time could possibly hope to reach.[6] The United Service Organizations, or USO, was founded in 1941 in response to a request from President Franklin D. Roosevelt to provide morale and recreation services to uniformed military personnel. This request led six civilian agencies -- the Salvation Army, Young Men's Christian Association, Young Women's Christian Association, National Catholic Community Service, National Travelers Aid Association and the National Jewish Welfare Board -- to unite in support of the troops.

The draft

In 1940 Congress passed the first draft legislation, which was led by Grenville Clark. It was renewed (by one vote) in summer 1941. It involved questions as who should control the draft, the size of the army, and the need for deferments. The system worked through local draft boards comprising community leaders who were given quotas and then decided how to fill them. There was very little draft resistance.[7]

The nation went from a surplus manpower pool with high unemployment and relief in 1940 to a severe manpower shortage by 1943. Industry realized that the army urgently desired production of essential war materials and foodstuffs more than soldiers. (Large numbers of soldiers were not used until the invasion of Europe in summer 1944.) In 1940-43 the Army often transferred soldiers to civilian status in the Enlisted Reserve Corps in order to increase production. Those transferred would return to work in essential industry, although they could be called back to active duty if the army needed them. Others were discharged completely if their civilian work was deemed absolutely essential. There were instances of mass releases of men to increase production in various industries---copper, for example.

Burning issues included the drafting of fathers, which was avoided as much as possible. The drafting of 18-year olds was desired by the military but vetoed by public opinion. Blacks and Asians were drafted at the same rate as whites. The experience of World War I regarding men needed by industry was particularly unsatisfactory--too many skilled mechanics and engineers became privates. Farmers demanded and were generally given occupational deferments (many volunteered anyway--but those who stayed at home lost postwar veterans benefits.)

Population movements

The war saw large-scale migration to industrial centers, especially on the West Coast. Millions of wives followed their husbands to military camps. Many new military training bases were established or enlarged, especially in the South. Large numbers of African Americans left the cotton fields, headed for the cities. Housing was increasingly difficult to find in industrial centers; commuting by car was limited by gasoline rationing. People car pooled or took public transportation, which was seriously overcrowded. Trains were heavily booked, so people limited vacation and long-distance travel. also people had to recycle many things such as tin cans glass metal steel etc.

Role of women

Women took on an active role in World War II.[8]

Employment

First, women took on many paid jobs in temporary new munitions factories, and in old factories that had been converted from civilian products like automobiles. This was the "Rosie the Riveter" phenomenon.

Second, they filled many traditionally female jobs that were created by the war boom--as waitresses, for example. Third they broke into jobs that had almost always been held by men--such as bank teller or shoe salesperson. In general when they replaced men they came with fewer skills. Industry retooled its machine jobs so that unskilled workers (women and men too) could handle them. (This opened many jobs for men who had been unemployed in the 1930s). Some unions tried to maintain the same pay scale as men had because they expected men to resume their jobs after the war.

Married women continued their usual household duties of cleaning, cooking, purchasing and nursing the sick, and added the new role of full-time paid worker. After 1945 they gave up their jobs and became housewives again. Historians also debate how much of that was voluntary and how much was involuntary.

Volunteer activities

Women staffed millions of jobs in community service roles, such as USO and Red Cross.[9]

Baby boom

Marriage and motherhood came back as prosperity empowered couples who had postponed marriage. The birth rate started shooting up in 1941, paused in 1944-45 as 12 million men were in uniform, then continued to soar until reaching a peak in the late 1950s. This was the "Baby Boom."

In a New-Deal-like move, the federal government set up the "EMIC" program that provided free prenatal and natal care for the wives of servicemen below the rank of sergeant.

Housing shortages, especially in the munitions centers, forced millions of couples to live with parents or in makeshift facilities. Little housing had been built in the depression years, so the shortages grew steadily worse until about 1948, when a massive housing boom finally caught up with demand. (After 1944 much of the new housing was supported by the GI bill.)

Federal law made it difficult to divorce absent servicemen, so the number of divorces peaked when they returned in 1946. In long-range terms, the divorce rates changed little.[10]

Housewives

The traditional role of housewife became easier because there was so much spending money available, and harder because of rationing, shortages, cutbacks in automobile and bus service, and migration from farms and towns to munitions centers. Those housewives who worked found the dual role difficult to handle.

The worst psychological pressure came when sons, husbands, brothers and fiances were drafted and sent to faraway training camps, preparing for a war in which nobody knew how many would be killed. Millions of wives tried to relocate near their husbands' training camps.[11]

Role of minorities

FEPC

The FEPC was created by a 1941 executive order #8802 by President Roosevelt requiring companies with government contracts not to discriminate on the basis of race or religion. It assisted African Americans in obtaining jobs in industry. It said "there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin." In 1943 Roosevelt greatly strengthened FEPC with a new executive order, #9346. It required that all government contracts have a non-discrimination clause. FEPC was the most significant breakthrough ever for Blacks and women on the job front. During the war the federal government operated airfield, shipyards, supply centers, ammunition plants and other facilities that employed millions. FEPC rules applied and guaranteed equality of employment rights. Of course, these facilities shut down when the war ended. In the private sector the FEPC was generally successful in enforcing non-discrimination in the North, it did not attempt to challenge segregation in the South, and in the border region its intervention led to hate strikes by angry white workers.[12]

African American: Double V campaign

The African American community in the United States resolved on a "Double V" campaign: Victory over Fascism abroad, and victory over discrimination at home. Large numbers migrated from poor Southern farms to munitions centers. Racial tensions were high in overcrowded cities like Chicago; Detroit and Harlem experienced race riots in 1943.[13]

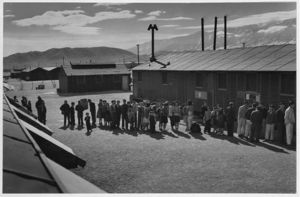

Internment of Japanese Americans

In 1942 the War Department demanded that all enemy nationals be removed from war zones on the West Coast. The question became how to evacuate the estimated 120,000 people of Japanese citizenship living in California. Roosevelt looked at the secret evidence available to him:[14] the Japanese in the Philippines had collaborated with the Japanese invasion troops; most of the adult Japanese in California had been strong supporters of Japan in the war against China. There was evidence of espionage compiled by code-breakers that decrypted messages to Japan from agents in North America and Hawaii before and after Pearl Harbor. On February 19, 1942 Roosevelt issued Executive Order #9066 which set up designated military areas "from which any or all persons may be excluded." The most controversial part of the order included American born children and youth who had dual U.S, and Japanese citizenship. In February 1943, when activating the 442nd Regimental Combat Team --a unit composed of U.S.-born American citizens of Japanese descent living in Hawaii, Roosevelt said, "No loyal citizen of the United States should be denied the democratic right to exercise the responsibilities of his citizenship, regardless of his ancestry. The principle on which this country was founded and by which it has always been governed is that Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart; Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry." In 1944, the Supreme Court upheld the legality of the executive order in the Korematsu v. United States case. The executive order remained in force until December when Roosevelt released the Japanese internees, except for those who announced their intention to return to Japan.

Italy was now an official enemy and citizens of Italy were also forced away from "strategic" coastal areas in California. All together 58,000 Italian citizens were forced to relocate. They relocated on their own and were not put in camps. Known spokesmen for Mussolini were arrested and held in prison. The restrictions were dropped in October 1942, and Italy switched sides in 1943 and became an American ally.

Wartime politics

Roosevelt easily won the bitterly contested 1940 election, but the Conservative coalition maintained a tight grip on Congress. In very light turnout in 1942 the Republicans made major gains. In the 1944 election Roosevelt defeated Tom Dewey in a close race that attracted little attention. Wendell Willkie, the defeated GOP candidate in 1940, became a roving ambassador for Roosevelt. Vice President Henry C. Wallace proved a poor administrator and after a series of squabbles Roosevelt stripped him of his administrative responsibilities and dropped him from the 1944 ticket, choosing instead Senator Harry S. Truman. Truman was best known for investigating waste, fraud and inefficiency in civilian programs.[15]

Propaganda and culture

The media cooperated with the federal government in presenting the official view of the war. All movie scripts had to be pre-approved, but there was no direct censorship of radio, newspapers or magazines.[16] World War II posters helped to mobilize a nation. Inexpensive, accessible, and ever-present, the poster was an ideal agent for making war aims the personal mission of every citizen. Government agencies, businesses, and private organizations issued an array of poster images linking the military front with the home front--calling upon every American to boost production at work and at home. Deriving their appearance from the fine and commercial arts, posters conveyed more than simple slogans. Posters expressed the needs and goals of the people who created them. By definition, wartime posters are naturally propagandistic, but most WW II posters were merely patriotically so. Some, however, resorted to gross racial and ethnic caricitures of the enemy, sometimes as hopelessly bumbling cartoon characters, sometimes as evil, half-human creatures.

One of the most noteworthy areas of civilian involvement during the war was in the area of recycling. Many everyday commodities were vital to the war effort, and drives were organized to recycle such things as rubber, tin, waste kitchen fats (the predominant raw material of explosives and many pharmaceuticals) paper, lumber, steel and many others. A popular phrase promoted by the government at the time was "Get some cash for your trash" (a nominal sum was paid to the donor for many kinds of scrap items) and "Fats" Waller recorded a song by the same title. Such commodities as rubber and tin remained highly important as recycled materials until the end of the war, while others, such as steel, were critically needed at first, but in lesser quantities as damaged war materials were returned from overseas for scrapping, lessening the need for civilian scrap metal drives. Once again, war propaganda played a prominent role in many of these drives.

A strong area of American culture even then was a fascination with celebrities, and many stars of Hollywood and radio gave service above and beyond the call in the donation of their time for everything from being Civilian Defense marshalls to making personal appearances at War Bond drives. Bonds were the money that financed the war, and Bond drives where celebrities appeared were always very successful. Several stars were responsible for personal appearance tours that netted multiple millions of dollars in bond pledges - an astonishing amount in 1943. The public paid roughly 2/3 of the face value of a war bond, and received the full face value back after a set number of years. While this may have represented a rather unspectacular interest rate, the government has never defaulted on payment of a single mature bond. People were challenged again and again to put "at least 10% of every paycheck into Bonds". Compliance was very high, with entire factories of workers earning a special flag to fly over their plant if all workers belonged to the "Ten Percent Club". There were seven major War Loan drives, all of which exceeded their goals. An added advantage was that citizens who were putting their money into War Bonds were not putting it into the home front wartime economy. There was a job for anyone who wanted one during the war, most of them well-paid. Personal income was at an all-time high, and more and more dollars were chasing fewer and fewer goods to purchase. This was a recipe for economic disaster that was largely avoided because Americans - cajoled daily by their government to do so - were also saving money at an all-time high rate, mostly in War Bonds, but also in private savings accounts and insurance policies.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Cantril, Hadley and Mildred Strunk, eds.; Public Opinion, 1935-1946 (1951), massive compilation of many public opinion polls from USA online edition

- Gallup, George Horace, ed. The Gallup Poll; Public Opinion, 1935-1971 3 vol (1972) esp vol 1. summarizes results of each poll as reported to newspapers

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1946 (1947) online

Surveys

- Adams, Michael C.C. The Best War Ever: America and World War II (1993); contains detailed bibliography

- Blum, John Morton V Was for Victory: Politics and American Culture During World War II (1995; original edition (1976)

- Kennedy, David M. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. (1999) online edition

- Polenberg, Richard. War and Society: The United States, 1941-1945 (1980)

- Resch, John Phillips et al eds. Americans at War: Society, Culture, and the Homefront vol 3 (2005), an encyclopedia

- Winkler, Allan M. Home Front U.S.A.: America During World War II (1986). short survey

- 10 Eventful Years: 1937-1946 4 vol. Encyclopedia Britannica, 1947. Highly detailed encyclopedia of events

Economy and labor

- Aruga, Natsuki. "'An' Finish School': Child Labor during World War II." Labor History 29 (1988): 498-530. online

- Campbell, D'Ann. "Sisterhood versus the Brotherhoods: Women in Unions" in Campbell, Women at War With America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (1984).

- Dubofsky, Melvyn and Warren Van Time John L. Lewis (1986). Biography of head of coal miners' union

- Evans Paul. "The Effects of General Price Controls in the United States during World War II." Journal of Political Economy 90 (1983): 944-66. statistical in JSTOR

- Faue, Elizabeth. Community of Suffering & Struggle: Women, Men, and the Labor Movement in Minneapolis, 1915-1945 (1991), social history online edition

- Feagin, Joe R., and Kelly Riddell. "The State, Capitalism and World War II: The U.S. Case." Armed Forces and Society 17 (fall 1990): 53-79. [abstract online

- Ferguson, Robert G. "One Thousand Planes a Day: Ford, Grumman, General Motors and the Arsenal of Democracy." History and Technology 2005 21(2): 149-175. ISSN 0734-1512 Fulltext in Swetswise, Ingenta and Ebsco

- George Q. Flynn; The Mess in Washington: Manpower Mobilization in World War II Greenwood Press. 1979. online edition*Fraser, Steve. Labor Will Rule: Sidney Hillman and the Rise of American Labor (1993). leader of CIO

- Harrison, Mark. "Resource Mobilization for World War II: The U.S.A., UK, U.S.S.R. and Germany, 1938-1945." Economic History Review 41 (1988): 171-92. in JSTOR

- Koistinen, Paul A. C. Arsenal of World War II: The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1940-1945 (2004) excerpt and text search

- Lichtenstein, Nelson. Labor's War at Home: The CIO in World War II (2003)

- Miller, Sally M., and Daniel A. Cornford eds. American Labor in the Era of World War II (1995), essays by historians, mostly on California online edition

- Maines, Rachel. "Wartime Allocation of Textiles and Apparel Resources: Emergency Policy in the Twentieth Century." Public Historian 7 (1985): 29-51.

- Mills, Geofrey, and Hugh Rockoff. "Compliance with Price Controls in the United States and the United Kingdom during World War II." Journal of Economic History 47 (1987): 197-213. in JSTOR

- Reagan, Patrick D. "The Withholding Tax, Beardsley Ruml, and Modern American Public Policy." Prologue 24 (1992): 19-31.

- Rockoff, Hugh. "The Response of the Giant Corporations to Wage and Price Controls in World War II." Journal of Economic History 41 (1981): 123-28. in JSTOR

- Romer, Christina D. "What Ended the Great Depression?" Journal of Economic History 52 (1992): 757-84. in JSTOR

- Tuttle, William M., Jr. "The Birth of an Industry: The Synthetic Rubber 'Mess' in World War II." Technology and Culture 22 (1981): 35-67. in JSTOR

- Vatter, Harold G. The U.S. Economy in World War II (1985) online edition

- Wilcox, Walter W. The farmer in the second world war (1947) online edition

- Yenne, Bill. The American Aircraft Factory in World War II. (St. Paul: Zenith, 2006. 192 pp. isbn 978-0-7603-2300-7.) Heavily illustrated.

The draft

- Blackstone, Robert C. "Democracy's Army: The American People and Selective Service in World War II." PhD dissertation : U. of Kansas 2005. 296 pp. DAI 2006 66(11): 4152-4153-A. DA3196030 online at ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Blum, Albert A. Drafted Or Deferred: Practices Past and Present Ann Arbor: Bureau of Industrial Relations, Graduate School of Business Administration, University of Michigan, 1967.

- Dechter, Aimée R., and Glen H. Elder, Jr. "World War II Mobilization in Men's Work Lives: Continuity or Disruption for the Middle Class?" American Journal of Sociology, volume 110 (2004), pages 761–793 online

- Flynn George Q. "American Medicine and Selective Service in World War II." Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 42 (1987): 305-26.

- Flynn George Q. The Draft, 1940-1973 (1993) (ISBN 0-7006-1105-3)

Gender and minorities

- Bailey, Beth, and David Farber; "The 'Double-V' Campaign in World War II Hawaii: African Americans, Racial Ideology, and Federal Power, " Journal of Social History Volume: 26. Issue: 4. 1993. pp 817+. in JSTOR

- Campbell, D'Ann. Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (1984)

- Dalfiume, Richard M. "The 'Forgotten Years'" of the Negro Revolution," Journal of American History, 55#1 (June 1968), 90-106. in JSTOR

- Daniel, Clete. Chicano Workers and the Politics of Fairness: The FEPC in the Southwest, 1941-1945 University of Texas Press, 1991

- Collins, William J. "Race, Roosevelt, and Wartime Production: Fair Employment in World War II Labor Markets," American Economic Review 91:1 (March 2001), pp. 272-286. in JSTOR

- Costello, John. Virtue Under Fire: How World War II Changed Our Social and Sexual Attitudes (1986), US and Britain

- Dower, John W. et al. eds. Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States, 1931–1945. (2006) 376 pp.; 400 color illustrations

- Garfinkel, Herbert. When Negroes March: The March on Washington and the Organizational Politics for FEPC (1959).

- Hartmann, Susan M. Home Front and Beyond: American Women in the 40's (1982)

- Kryder, Daniel.Divided Arsenal: Race and the American State During World War II (2001)

- Lees, Lorraine M. "National Security and Ethnicity: Contrasting Views during World War II." Diplomatic History 11 (1987): 113-25.

- Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944)

- Records of the Women's Bureau (1997), short essay on women at work

- Ward, Barbara McLean ed. Produce and Conserve, Share and Play Square: The Grocer and the Consumer on the Home-Front Battlefield during World War II, Portsmouth, NH: Strawbery Banke Museum

- Wynn, Neil A. The Afro-American and the Second World War (1993) online edition

Politics and Washington

- Brinkley, David. Washington Goes to War (1988).

- Burns, James MacGregor. Roosevelt: Soldier of Freedom 1940-1945 (1970), vol. 2: excerpt and text search vol 2; major interpretive scholarly biography, emphasis on politics; vol 2 is on war years and is online at ACLS e-books

- Freidel, Frank. Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Rendezvous with Destiny (1990), One-volume scholarly biography; covers entire life excerpt and text search 2006 reprint edition

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II (1995), joint biography by scholar excerpt and text search

- Graham, Otis L. and Meghan Robinson Wander, eds. Franklin D. Roosevelt: His Life and Times. (1985). encyclopedia

- Hooks Gregory. The Military Industrial Complex: World War II's Battle of the Potomac (1991).

- Jeffries John W. "The 'New' New Deal: FDR and American Liberalism, 1937-1945." Political Science Quarterly (1990): 397-418. in JSTOR

- Leff Mark H. "The Politics of Sacrifice on the American Home Front in World War II." Journal of American History 77 (1991): 1296-1318. in JSTOR

- Rhodes Richard. The Making of the Atomic Bomb (1986).

- Steele Richard W. "The Great Debate: Roosevelt, the Media, and the Coming of the War, 1940-1941." Journal of American History 71 (1994): 69-92. in JSTOR

Propaganda, advertising, media, public opinion

- Bentley, Amy. Eating for Victory: Food Rationing and the Politics of Domesticity. U. of Illinois Press, 1998. 238

- Bredhoff, Stacey. Powers of Persuasion: Poster Art from World War II, (1994)

- Cantril, Hadley, and Mildred Strunk, eds. Public Opinion: 1935-1946 (1951), massive compilation of polling data; online edition

- Fox, Frank W. Madison Avenue Goes to War: The Strange Military Career of American Advertising, 1941-45, (1975)

- Fyne, Robert The Hollywood Propaganda of World War II, (1994),

- Gregory, G.H. Posters of World War II, (1993)

- Gallup, George H. The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion 1935- 1971, Vol. 1, 1935-1948, (1972), short summary of every poll

- M. Paul Holsinger and Mary Anne Schofield; Visions of War: World War II in Popular Literature and Culture (1992) online edition

- Jones, John Bush. The Songs That Fought the War: Popular Music and the Home Front, 1939–1945. (2006) isbn 978-1-58465-443-8

- Steele Richard W. "The Great Debate: Roosevelt, the Media, and the Coming of the War, 1940-1941." Journal of American History 71 (1994): 69-92. in JSTOR

- Witkowski, Terrence H. "World War II Poster Campaigns: Preaching Frugality to American Consumers" Journal of Advertising, Vol. 32, 2003

Social, state and local history

- Brown DeSoto. Hawaii Goes to War. Life in Hawaii from Pearl Harbor to Peace. 1989.

- Clive Alan. State of War: Michigan in World War II University of Michigan Press, 1979.

- Daniel Pete. "Going among Strangers: Southern Reactions to World War II." Journal of American History 77 (1990): 886-911.

- Gleason Philip. "Pluralism, Democracy, and Catholicism in the Era of World War II." Review of Politics 49 (1987): 208-30.

- Hartzel, Karl Drew. The Empire State At War (1949), on upstate New York online edition

- Johnson Marliynn S. "War as Watershed: The East Bay and World War II." Pacific Historical Review 63 (1994): 315-41.

- T. A Larson. Wyoming's war years, 1941-1945 (1993)

- Lichtenstein Nelson. "The Making of the Postwar Working Class: Cultural Pluralism and Social Structure in World War II." Historian 51 (1988): 42-63.

- Lee James Ward, Carolyn N. Barnes, and Kent A. Bowman, eds. 1941: Texas Goes to War University of North Texas Press, 1991.

- Miller Marc. The Irony of Victory. World War II and Lowell, Massachusetts University of Illinois Press, 1988.

- Nash Gerald D. The American West Transformed. The Impact of the Second World War Indiana University Press, 1985.

- Smith C. Calvin. War and Wartime Changes: The Transformation of Arkansas, 1940-1945 University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

- Tuttle Jr. William M.; Daddy's Gone to War: The Second World War in the Lives of America's Children Oxford University Press, 1995 online edition

- O'Brien, Kenneth Paul and Lynn Hudson Parsons, eds. The Home-Front War: World War II and American Society (1995) online essays by scholars

- Watters, Mary. Illinois in the Second World War. 2 vol (1951)

External links

- Academic Data Related to the Roosevelt Administration

- FDR Cartoon Archive

- National Museum of the Civil Air Patrol (online, WWII section)

- Powers of Persuasion: Poster Art from World War II, National Archives

- Northwestern U Library World War II Poster Collection

- War Ration Book Records and Related Information

References

- ↑ Bernard Baruch, The Public Years, (1957) pp 321?28; Kerry E. Irish, "Apt Pupil: Dwight Eisenhower and the 1930 Industrial Mobilization Plan" The Journal of Military History 70.1 (2006) 31-61.

- ↑ Vatter, The U.S. Economy in World War II 1985.

- ↑ Koistinen, Arsenal of World War II (2004); Vatter, The U.S. Economy in World War II 1985.

- ↑ Miller and Cornford eds. American Labor in the Era of World War II (1995)

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Labor's War at Home: The CIO in World War II (2003)

- ↑ Campbell, Women at War with America (1984)

- ↑ Flynn, The Draft, 1940-1973 (1993)

- ↑ Campbell, Women at War with America (1984)

- ↑ Campbell, Women at War with America (1984)

- ↑ Campbell, Women at War with America (1984)

- ↑ Campbell, Women at War with America (1984)

- ↑ Garfinkel. When Negroes March (1959).

- ↑ Wynn. The Afro-American and the Second World War (1977)

- ↑ Keith Robar, Intelligence, Internment & Relocation: Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066: How Top Secret "MAGIC" Intelligence Led to Evacuation (2000)

- ↑ Brinkley, Washington Goes to War (1988)

- ↑ Fox, Madison Avenue Goes to War (1975)