User:Milton Beychok/Sandbox: Difference between revisions

imported>Milton Beychok |

imported>Milton Beychok No edit summary |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

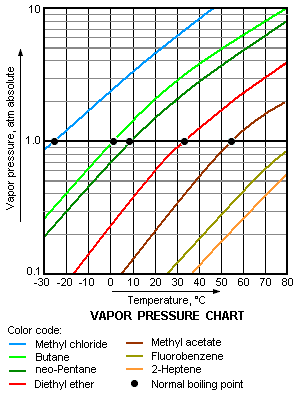

The higher is the vapor pressure of a liquid, the higher is the volatility and the lower is the normal boiling point of the liquid. The adjacent vapor pressure chart graphs the dependency of vapor pressure upon temperature for a variety of liquids<ref>{{cite book|author=R.H. Perry and D.W. Green (Editors)|title=Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook | edition=7th Edition|publisher=McGraw-Hill|year=1997|id=ISBN 0-07-049842-5}}</ref> and also confirms that liquids with higher vapor pressures have lower normal boiling points. | The higher is the vapor pressure of a liquid, the higher is the volatility and the lower is the normal boiling point of the liquid. The adjacent vapor pressure chart graphs the dependency of vapor pressure upon temperature for a variety of liquids<ref>{{cite book|author=R.H. Perry and D.W. Green (Editors)|title=Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook | edition=7th Edition|publisher=McGraw-Hill|year=1997|id=ISBN 0-07-049842-5}}</ref> and also confirms that liquids with higher vapor pressures have lower normal boiling points. | ||

For example, at any given temperature, methyl chloride (CH<sub>3</sub>Cl) has the highest vapor pressure of any of the liquids graphed in the chart. It also has the lowest normal boiling point (− 24 °C), which is where its vapor pressure curve (the blue line) intersects the horizontal pressure line of one [[atmosphere (unit)|atmosphere]] (atm) of absolute vapor pressure. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 11:21, 20 September 2010

In chemistry and physics, volatility is a term used to characterize the tendency of a substance to vaporize.[1] It is directly related to a substance' s vapor pressure. At a given temperature, a substance with a higher vapor pressure will vaporize more readily than a vapor with a lower vapor pressure.[2][3][4]

Any substance with a significant vapor pressure at temperatures of about 20 – 25 °C (68 – 77 °F) is very often referred to as being volatile.

In common usage, the term applies primarily to liquids. However, it may also be used to characterize the process of sublimation by which certain solid substances such as ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) and dry ice, which is solid carbon dioxide (CO2), change directly from their solid form to a vapor without becoming a liquid.

Any substance with a significant vapor pressure at temperatures of about 20 – 25 °C (68 – 77 °F) is very often referred to as being volatile.

Vapor Pressure, temperature and boiling point

The vapor pressure of a substance is the pressure at which its gaseous (vapor) phase is in equilibrium with its liquid or solid phase. It is a measure of the tendency of molecules and atoms to escape from a liquid or solid. A liquid's boiling point at atmospheric pressure corresponds to the temperature at which its vapor pressure is equal to the surrounding atmospheric pressure and is very commonly referred to as the normal boiling point.

The higher is the vapor pressure of a liquid, the higher is the volatility and the lower is the normal boiling point of the liquid. The adjacent vapor pressure chart graphs the dependency of vapor pressure upon temperature for a variety of liquids[5] and also confirms that liquids with higher vapor pressures have lower normal boiling points.

For example, at any given temperature, methyl chloride (CH3Cl) has the highest vapor pressure of any of the liquids graphed in the chart. It also has the lowest normal boiling point (− 24 °C), which is where its vapor pressure curve (the blue line) intersects the horizontal pressure line of one atmosphere (atm) of absolute vapor pressure.

References

- ↑ Note: To vaporize means to become a vapor.

- ↑ Gases and Vapor (University of Kentucky website)

- ↑ James G. Speight (2006). The Chemistry and Technology of Petroleum, 4th Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-9067-2.

- ↑ Kister, Henry Z. (1992). Distillation Design, 1st Edition. McGraw-hill. ISBN 0-07-034909-6.

- ↑ R.H. Perry and D.W. Green (Editors) (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook, 7th Edition. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049842-5.

Bibliography:

- Lawrence K. Wang, Norman C. Pereira and Yung-Tse Hung (Editors) (2004). Air Pollution Control Engineering, 1st Edition. Humana Press. ISBN 1-58829-161-8.