Joan of Arc: Difference between revisions

imported>Meg Taylor m (spelling: annointed -> anointed) |

imported>John Stephenson m (moved Joan of Arc/Draft to Joan of Arc: citable version policy) |

Revision as of 04:39, 4 September 2013

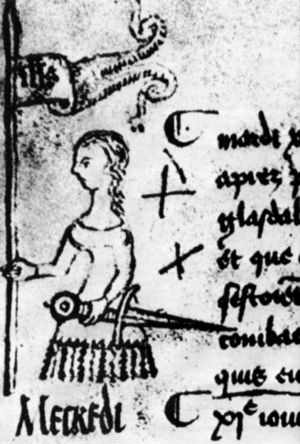

Joan of Arc[1] (ca. 1412 – 30 May 1431)[2] was a French peasant girl who, while still a teenager, and in obedience to what she asserted to be a command from God, led her nation's armies to several spectacular military victories which turned the tide in the Hundred Years' War at a time when the French cause was tottering on the brink of collapse. Soon thereafter, she was captured and tried by an English-backed Church court which convicted her of heresy and had her burnt at the stake.

Following the Hundred Years' War, Joan was posthumously exonerated by a Papal commission which denied the legality of her original trial and overturned the verdict. A French national heroine due to her life and deeds, in 1920 she was canonized as a Saint by the Roman Catholic Church.

Background

Since 1337, the French and English had been locked in a protracted war, punctuated by intermittent periods of tense peace, known to history as the Hundred Years' War. The fighting had left the French economy devastated and the French themselves divided into factions known as the Armagnacs and the Burgundians.

In 1420, the Burgundians and the English entered into the Treaty of Troyes, in which Charles, the Dauphin and heir to the French throne, was disinherited and the French royal succession was granted to the heirs of King Henry V of England. In 1422 Henry V died leaving an infant son as heir to both the English and French thrones.

By the Fall of 1428, the English and their Burgundian allies controlled nearly all of France north of the Loire River as well as Aquitaine in the southwest and had laid siege to Orléans, the only French city on the Loire still loyal to Charles. The fall of Orléans was imminently expected, opening the way to an invasion of the remaining French territory. This was the situation when Joan of Arc first stepped onto the stage of world history.

Life

Childhood

Joan of Arc was one of five children (3 boys and 2 girls) born to Jacques d'Arc and Isabelle Romée in Domrémy, then a small village on the banks of the River Meuse in northeastern France. The village, which remained loyal to the French crown, was in an area of patchwork loyalties surrounded by Burgundian lands. Several local raids occurred during Joan of Arc's childhood and on one occasion her village was burned.

Her parents were prosperous peasants who had a small landholding and her father, in addition to his farming work, held a minor position of authority in the local village.

Joan herself had an outwardly normal, unremarkable childhood. She experienced a religious upbringing from her devout mother and was noted for being of a good nature, simple and pious. She spent her time engaged in typical activities for girls of that time and place - spinning, weaving, and tending or watching over the animals.

One other noteworthy event in Joan's childhood occurred when she was hailed to Toul to answer a breach of promise case in re marriage. The judge dismissed the case against her, ruling that Joan had in fact not made such a promise. The outcome of this case disappointed her parents who would have preferred to see her married. But Joan was acting in obedience to a higher calling.

Divine calling

According to Joan's testimony at her Trial in Rouen, some time in the summer of her thirteenth year (which would be in 1424 or possibly 1425), an event occurred which was to be the harbinger of one of the most remarkable sequence of events in recorded history. For it was then that Joan, in her father's garden, first heard the voices which set in motion her subsequent journey and activity and which later figured so prominently in the minds of her contemporaries and also of modern students of history.

Initially frightened by the experience, she decided that the voice was that of an angel and had been sent to her from God. Before long, she had identified that voice as that of St. Michael who told Joan that she should expect further visits from St. Catherine and St. Margaret and that they would provide her with guidance and counsel.

By 1428, this guidance and counsel had coalesced to, among other matters concerned with good character and the like, telling her to go the the King's court to, in her words, "raise the siege of Orléans and lead the Dauphin to Reims to be crowned and anointed".

The Road to Orléans

Before going to the King's court at Chinon, Joan, at the behest of her voices, first had to go to Vaucouleurs in order to gain an escort from the captain of that garrison town, Robert de Baudricourt. In the spring of 1428, she left Domrémy in secret, accompanied by a kinsman, Durand Laxart, for Vaucouleurs. Her petition to Sir Robert was rebuffed and she returned to Domrémy.

She returned the following January and gained support from two men of standing: Jean de Metz and Bertrand de Poulengy. Under their auspices she was granted a second interview with Baudricourt at which time she gained his support.[3] Several days later, Joan left Vaucouleurs with an escort of six men for Chinon to meet with the Dauphin.

Travelling much of the time at night and in male attire to avoid detection, Joan arrived at the King's castle in Chinon in early March of 1429. Soon after her arrival, she met in private with the Dauphin. This meeting, and the sign which she gave to Charles as a token of her authenticity, has become the subject of intense speculation beginning with her Trial in Rouen and continuing through the centuries since.[4]

Following this initial meeting, Charles elected to send her to Poitiers in order that she be examined by theologians appointed for this purpose. Among other matters, the prelates at Poitiers questioned Joan about her assumption of male attire, inquired into her character, way of life, and sincerity, and considered the question of her faith and orthodoxy. Although the records of the Poitiers examination have not survived, it is known that the theologians charged with the investigation found no fault with her on any of these points. Upon consideration by the King's council, the report of the Poitiers investigators was approved. Joan would appeal to the record of the Poitiers investigation on several occasions during her Trial in Rouen.

In the meantime, Charles had been assembling a relief force for the purpose of lifting the siege at Orléans. When Joan returned from Poitiers, she was outfitted with the accoutrements of a knight and sent with this force to Orléans where she arrived on the 29th of April.

Military successes

Joan's position in the French forces at Orléans was initially viewed with mixed feelings by her fellow commanders. Many regarded her very lightly, others were hostile. In the week following her arrival at Orléans, a number of heated discussions took place regarding military plans and tactics with Joan always opting for a very aggressive military approach in contrast to previous French tactics.

Following some preliminary engagements wherein some of the smaller English fortifications were captured, a French force led by Joan assaulted and captured the English position in front of the stronghold of Les Tourelles, leaving the English garrison in the Tourelles isolated.

In opposition to the other military commanders who wanted to wait for reinforcements before undertaking further action, Joan prepared for a direct assault on the fortress the next day (May 7). After an entire day of fighting, with the assault having to be renewed in the evening, the fortress was taken with all its defenders either killed or captured. The following day, the English forces in the remaining forts abandoned the field and the siege of Orléans was over.

In the weeks following the victory at Orléans, the French army benefitted from a great upsurge in morale and enthusiasm. While volunteers swelled the ranks and materiel was being gathered, the French commanders debated what course of action should be undertaken next. In the end, it was decided that the remaining English strongholds in the Loire River valley should be cleared as a prelude to Joan's proposal of an advance northwards to Reims so that Charles might be crowned in accordance with traditional coronation ceremonies.

In the space of about a week beginning in the middle of June, the remaining major English positions in the Loire River valley - at Jargeau, Meung-sur-Loire, and Beaugency - were cleared.

Meanwhile, an English relief force under the command of Sir John Fastolf was approaching the area and arrived just north of Beaugency on the 18th, though too late to aid in the relief of that garrison. As this relief force retreated northwards, they were pursued by the French army and in an engagement which has been compared to the Battle of Agincourt, though with a reversal of results, the English were routed at Patay.

During the military actions at Orléans and in the Loire valley, Joan twice sustained wounds (an arrow wound at Orléans and the other when she was struck on the head by a stone cannonball while climbing a scaling ladder). It was also as a result of the actions up to this time that Joan won the support of the major French military commanders. This set the stage for the march north to Reims and the coronation of Charles VII as King of France.

The French held a war council in late June in order to determine what course of action should be undertaken next. Many of those concerned favored a thrust into English Normandy, but Joan urged a march through Burgundian held territory to Reims in order to coronate the King and complete the mission she claimed to have from God. Having decided in favor of this latter approach, the army left Gien for Reims on June 29.

En route to Reims, the army received the submission of several Burgundian towns with only a brief holdup at Troyes. There a French war council briefly considered retreating but, after consulting with Joan, the French forces began siege operations and soon thereafter the Anglo-Burgundian garrison abandoned the city. The keys to the city of Reims were given to the King on July 16 and he entered the city on that date, accompanied by Joan. The coronation was held the following day, with Joan standing at the King's side.

Setbacks, capture and imprisonment

Following the coronation, Charles pursued a policy of attempting to drive a wedge into the Anglo-Burgundian alliance. In pursuit of this, he entered into secret negotiations with the Burgundians, the result of which was, in early August, the conclusion of a two week truce. Joan, for her part, was intent on taking Paris and, when she found out about the truce, expressed her strong disapproval.

Throughout the rest of the month of August, the rival armies maneuvered in and around Paris, avoiding any direct major battles, but with numerous cities and towns surrendering peacefully to the cause of Charles. Then, in late August, a four month armistice was concluded between Charles and the Burgundians. However, Paris was not included in the terms of this agreement and the French army gathered before Paris in early September.

On the 8th of September (a holy day, a fact which would be brought up at Joan's Trial in Rouen), the French forces assaulted the city of Paris itself, relying in part on a simultaneous uprising within the city. The assault failed, with Joan being wounded in the leg by a crossbow bolt. Although Joan and many of the commanders wanted to renew the assault on the following day, they were ordered by Charles to break off and the French army then retreated southwards towards the Loire.

Following some minor actions over the winter of 1429-30, the Duke of Burgandy launched an offensive. In May, Joan went to Compiègne to defend against the siege which the Anglo-Burgundian forces had begun. On the 23rd of May, 1430, she was captured by Burgundian forces during a minor skirmish on the outskirts of the town.

Over the course of the next several months, she was held in various castles, on at least two occasions attempting to escape. Meanwhile, earnest negotiations for her transfer to stand trial for heresy took place. Eventually, she was surrendered to the English in exchange for a large sum of money and taken to Rouen, the administrative capital of the English forces in France.

Trial and execution

The proceedings against the captive Joan began on January 9, 1431 in the castle of Rouen. The judge in the case, Pierre Cauchon, had invoked the Inquisition. Under the rules of the Inquisition, in order to formally inaugurate the proces d'office, as it was called, it was first necessary that there be a diffamatio, or public talk of wrongdoing.

In order to support this aspect of the trial, Cauchon ordered an inquiry to be made into her morals, character, and life. This involved an examination in order to determine her virginity as well as envoys who travelled to Domrémy and elsewhere throughout France to collect information from witnesses about Joan. As a result of these inquiries, Cauchon concluded that the conditions for a finding of a diffamatio existed in Joan's case, thus satisfying the necessary preconditions to begin a formal interrogation.

After the necessary preparations for the trial were complete, consisting mainly of assembling the assessors (judges) and others, Joan was brought before her judges for interrogation. This part of the proceedings, which took place preliminary to the filing of formal charges being levelled against her, began on February 21. At first the sessions were held in public, but after it became clear that Joan was gaining sympathy among the people of Rouen, the sessions were transferred to prison and held in secret.

It was only on March 26, after the drafting of 70 articles (charges) were drawn up based on the previous interrogation, that the regular (or ordinary) trial sessions began. By early April, the assessors had re-worked the original 70 articles into a final list of 12 articles (charges). The most important charges concerned the nature of her voices and visions and whether they were from God, her assumption of male attire, and her attitude towards the authority of the Church.

Threatened with immediate execution by burning at the stake and promised transfer to a church prison where she would not be under the guard of English soldiers, Joan signed an abjuration in late May. But upon being returned to the English prison and possibly molested by her captors, and in obedience to her voices who told her that she had done a bad thing (to sign the abjuration), she then renounced her previous abjuration and was brought to trial a second time, this time as a relapsed heretic, the penalty for which was death by burning.

On May 30, 1431, the sentence of death by burning was carried out in the market square of the town of Rouen.

Aftermath and rehabilitation

Fighting in the Hundred Years' War continued for over two decades following Joan's death, but the tide had turned and the impetus to the French cause given by Joan's career would not be stemmed.

Although the English staged a rival coronation in Paris of the young Henry VI, the effect on public opinion was, if anything, negative. The English suffered some military reversals around Paris the following year and negotiations between the Duke of Burgundy and Charles VII were begun shortly thereafter. These negotiations eventually resulted in the Treaty of Arras (1435) which ended the Anglo-Burgundian alliance.

Paris fell to the French in 1437 and, by 1450, the English were routed from their remaining strongholds in Normandy. The final act in the Hundred Years' War was played out at Castillon in July of 1453 when the Engish were finally expelled from Aquitaine, their last remaining foothold in France. Meanwhile, the process leading to Joan's rehabilitation had already begun.

In 1449, the city of Rouen opened its gates to the forces of Charles VII and the trial records became available. With the war drawing to a close, early the following year (15 February 1450), Charles appointed Guillaume Bouillé to study the records to ascertain the facts about the original Trial.

Bouillé took depositions from several participants in the Trial, including Guillaume Manchon, the principal notary at the Trial, and Jean Beaupère, who was the principal interrogator at the Trial. All but one testified to judicial bias, English pressure and numerous procedural violations. Bouillé then drew up a summary and delivered it to Charles.

In February of 1452, Cardinal d'Estouteville, the Papal legate to France, met with Charles and contacted Inquisitor General Jean Bréhal concerning the matter. Later that year, in May, Bréhal produced a critique of the original Trial consisting of 12 articles, including the charge that Cauchon was biased and that he was not legally empowered to conduct the Trial.

Finally, in response to a petition from Joan's mother, Pope Calixtus III authorized an inquiry into the original Trial. On November 7, 1455, a Papal commission headed by Jean Juvénel des Ursins, the Archbishop of Reims, began its work with hearings in Paris.

The Commission took testimony from over a hundred witnesses, including noted jurists and theologians, those who were present at the original Trial, as well as her childhood friends and acquaintances who were questioned about her piety and virtue, her activities as a child, and other matters which had been examined at the Trial. The original list of 12 articles was expanded to 27 points and submitted to theologians and canon law experts who pronounced in favor of Joan.

After the verdict of the nullification Trial was released, the original 12 articles of indictment were formally read and termed "iniquitous, false, prepared in a lying manner without reference to Joan's confessions".

Notes

- ↑ At her Trial in 1431, when asked about her name and surname, Joan replied, "in my own country, I was called Jeannette, and after I came to France, I was called Jeanne". The name by which she is commonly known today in the English speaking world - Joan of Arc - is an Anglicization of Jeanne Darc (the latter with a wide variety of spellings) and was not known to Joan herself in either its French or Anglicized versions. See Pernoud and Clin, pp. 220–221 for a more complete discussion of Joan's name.

- ↑ A birthdate of 6 January for Joan is often cited. At her Trial in 1431, Joan of Arc herself stated that she was "about" or "around" 19 years of age, not giving a precise date of birth. In testimony given during the rehabilitation hearings of the 1450s, numerous witnesses who had known Joan in Domrémy, or who were present at her birth, used a similar formula to state their (or Joan's) age: that is, so many years of age, or thereabouts. This was in fact the typical way of reporting one's age at the time. It was not common for parish records to record births of those who were not noble until many years later. The date of 6 January is based on the testimony of a single witness, not from Domrémy.

- ↑ A story has gained currency in some quarters that Baudricourt's support was gained as a result of her (Joan's) prediction concerning a French military reversal, a prediction which, according to this version, was confirmed when news of the Battle of the Herrings arrived some time later. The story is not accepted in all quarters.

- ↑ There are two main points of speculation or interest in this regard. The first concerns the story, which is very widely repeated and has garnered a considerable amount of credibility, that the Dauphin had hidden himself, incognito, among the courtiers as a test to see whether or not Joan could recognize him in spite of the subterfuge. When she did so, according to this report, her stock at court rose considerably. The second main question concerns the nature of the sign given by Joan to Charles, a question which greatly interested the assessors at her Trial, who repeatedly questioned Joan in that regard. This question (as to the nature of the "sign" given to Charles) has also been the subject of much interest and speculation among present-day historians, though, as can be expected in such matters, no firm conclusions are likely ever to be drawn.

Further reading

- Kelly DeVries, Joan of Arc: a Military Leader. Sutton Publishing Ltd, Great Britain, 1999. ISBN 0-7509-1805-5.

- Fresh Verdicts on Joan of Arc, edited by Bonnie Wheeler and Charles T. Wood. Garland Publishing, Inc, New York and London, 1996. ISBN 0-8153-3664-0.

- Régine Pernoud, Joan of Arc, by Herself and Her Witnesses. Scarborough House, Lanham, MD, 1994. ISBN 0-8128-1260-3.

- Régine Pernoud and Marie Veronique-Clin, Joan of Arc: Her Story (revised and translated by Jeremy Duquesnay Adams and edited by Bonnie Wheeler). St. Martins Press, New York, 1998. ISBN 0-312-21442-1.

- Stephen Richey, Joan of Arc: the Warrior Saint. Praeger Publishers, 2003. ISBN 0275981037.

- Donald Spoto, Joan: the Mysterious Life of the Heretic who became a Saint. HarperSanFrancisco, 2007. ISBN 0-06-081517-5

- Marina Warner, Joan of Arc, the Image of Female Heroism. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 1981. ISBN 0-520-22464-7.

- Timothy Wilson-Smith, Joan of Arc: Maid, Myth, and History, Sutton Publishing, 2006, ISBN 0-7509-4341-6

See also

Internet resources

- The text of the condemnation trial

- International Joan of Arc Society (Bonnie Wheeler, Director)

- Catholic Encyclopedia entry for St. Joan of Arc.

- The Jeanne d'Arc Centre biography and research.

- Jeanne-darc.dk Various materials including a complete English translation of the rehabilitation trial transcript.

- Joan of Arc Archive by Allen Williamson. Includes a biography, translations, and other original research.

- Joan of Arc Museum in Rouen, France.

- Journal of Joan of Arc Studies Academic journal.

- St. Joan of Arc Center of Albuquerque, New Mexico, maintained by Virginia Frohlick.

- Editable Main Articles with Citable Versions

- CZ Live

- History Workgroup

- Military Workgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- History Content

- Military Content

- History tag

- Military tag

- History Workgroup Draft

- Religion Workgroup Draft

- Military Workgroup Draft

- Pages using ISBN magic links