Schröder-Bernstein theorem: Difference between revisions

imported>Peter Schmitt (→Details: decreasing) |

imported>John Stephenson m (moved Schröder-Bernstein theorem/Draft to Schröder-Bernstein theorem: citable version policy) |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} {{TOC|right}} | {{subpages}} {{TOC|right}} | ||

The '''Schröder-Bernstein theorem''' (sometimes '''Cantor-Schröder-Bernstein theorem''') is a fundamental theorem of [[set theory]]. | <onlyinclude> | ||

The '''[[Schröder-Bernstein theorem]]''' (sometimes '''Cantor-Schröder-Bernstein theorem''') is a fundamental theorem of [[set theory]]. | |||

Essentially, it states that if two sets are such that each one has at least as many elements as the other | Essentially, it states that if two sets are such that each one has at least as many elements as the other | ||

then the two sets have equally many elements. | then the two sets have equally many elements. | ||

| Line 9: | Line 10: | ||

In analogy to this theorem the term [[Schröder-Bernstein property]] is used | In analogy to this theorem the term [[Schröder-Bernstein property]] is used | ||

in other contexts to describe similar properties. | in other contexts to describe similar properties. | ||

<noinclude> | |||

== The Schröder-Bernstein theorem == | == The Schröder-Bernstein theorem == | ||

</noinclude> | |||

'''Theorem.''' | '''Theorem.''' | ||

If for two sets ''A'' and ''B'' there are | If for two sets ''A'' and ''B'' there are | ||

| Line 29: | Line 30: | ||

'''Remark.''' | '''Remark.''' | ||

It is of theoretical interest that the proof of the theorem does not depend on the [[Axiom of Choice]]. | It is of theoretical interest that the proof of the theorem does not depend on the [[Axiom of Choice]]. </onlyinclude> | ||

== History == | |||

As it is often the case in mathematics, the name of this theorem does not truly reflect its history. | |||

The traditional name "Schröder-Bernstein" is based on two proofs published independently in 1898. | |||

Cantor is often added because he first stated the theorem in 1895, | |||

while Schröder's name is often omitted because his proof turned out to be flawed | |||

while the name of the mathematician who first proved it is not connected with the theorem. | |||

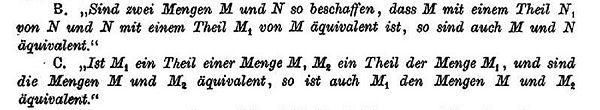

{{Image|Cantor1895.MA46.484-BC.jpg|right|600px|Georg Cantor (1895) states the theorem (B.)}} | |||

In reality, the history was more complicated: | |||

* '''1887''' [[Richard Dedekind]] proves the theorem but does not publish it. | |||

* '''1895''' [[Georg Cantor]] states the theorem in his first paper on set theory and transfinite numbers (as an easy consequence of the linear order of cardinal numbers which he was going to prove later). | |||

* '''1896''' [[Ernst Schröder]] announces a proof (as a corollary of a more general statement). | |||

* '''1897''' [[Felix Bernstein]], a young student in Cantor's Seminar, presents his proof. | |||

* '''1897''' After a visit by Bernstein, Dedekind independently proves it a second time. | |||

* '''1898''' Bernstein's proof is published by [[Émile Borel]] in his book on functions. (Communicated by Cantor at the 1897 congress in Zürich.) | |||

Both proofs of Dedekind are based on his famous memoir ''Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen?'' | |||

and derive it as a corollary of a proposition equivalent to statement C in Cantor's paper: | |||

:<math> | |||

A \subset B \subset C \quad\textrm{and}\quad |A|=|C| \qquad\Rightarrow\qquad |A|=|B|=|C| | |||

</math> | |||

Cantor observed this property as early as 1882/83 during his studies in set theory and transfinite numbers | |||

and therefore (implicitly) relying on the Axiom of Choice. | |||

== Proof == | == Proof == | ||

| Line 50: | Line 77: | ||

if performed on ''A''<sub>1</sub>, gives ''A''<sub>1</sub> as a result. (Thus ''A''<sub>1</sub> is a ''fixed point''.) | if performed on ''A''<sub>1</sub>, gives ''A''<sub>1</sub> as a result. (Thus ''A''<sub>1</sub> is a ''fixed point''.) | ||

: Take a subset of ''A'', find its image under ''f'' in ''B'', take the complement, find its image under ''g'' in ''A'', and, finally, take the complement. | : Take a subset of ''A'', find its image under ''f'' in ''B'', take the complement, find its image under ''g'' in ''A'', and, finally, take the complement. | ||

This defines a mapping of subsets of ''A'' to subsets of ''A'' that is | This defines a mapping of subsets of ''A'' to subsets of ''A'' that is increasing, and such a mapping always has a fixed point. | ||

=== Proof === | === Proof === | ||

| Line 63: | Line 90: | ||

\sigma (S) := A \setminus g_\ast ( B \setminus f_\ast (S) ) \quad ( S \subset A ) | \sigma (S) := A \setminus g_\ast ( B \setminus f_\ast (S) ) \quad ( S \subset A ) | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

on the power set of ''A'' is monotone | on the power set of ''A'' is monotone increasing | ||

: <math> S_1 \subset S \subset A | : <math> S_1 \subset S \subset A | ||

\Rightarrow \sigma (S_1) \subset \sigma (S) | \Rightarrow \sigma (S_1) \subset \sigma (S) | ||

| Line 86: | Line 113: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

(2) σ is a monotone function on the power set of ''A'': | (2) σ is a monotone increasing function on the power set of ''A'': | ||

: <math> | : <math> | ||

S_1 \subset S | S_1 \subset S | ||

| Line 101: | Line 128: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

(3) Any monotone | (3) Any monotone increasing function on a power set has a fixed point ''A''<sub>1</sub>: | ||

: <math> \sigma(A) \in \mathcal A := \{ \sigma(S) \mid \sigma(S) \subset S \subset A \} | : <math> \sigma(A) \in \mathcal A := \{ \sigma(S) \mid \sigma(S) \subset S \subset A \} | ||

\Rightarrow \mathcal A \not= \emptyset | \Rightarrow \mathcal A \not= \emptyset | ||

| Line 117: | Line 144: | ||

\Rightarrow \sigma (A_1) = A_1 | \Rightarrow \sigma (A_1) = A_1 | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

(4) ''h'' is well-defined and injective because ''f'' and ''g'' are injective and ''g''<sup>−1</sup> is defined on the complement of ''A''<sub>1</sub>: | |||

: <math> | |||

A \setminus ( g_\ast ( B \setminus f_\ast (A_1) ) ) = \sigma (A_1) = A_1 = A \setminus ( A \setminus A_1 ) | |||

</math> | |||

:: <math> | |||

\Rightarrow g_\ast ( B \setminus f_\ast (A_1) ) = A \setminus A_1 | |||

</math> | |||

: Moreover, this also shows that ''h'' is bijective because it follows that the image of A under ''h'' is | |||

:: <math> | |||

f_\ast (A_1) \cup g^{-1} ( A \setminus A_1 ) = f_\ast (A_1) \cup ( B \setminus f_\ast (A_1) ) = B | |||

</math> | |||

: In other words, ''A''<sub>1</sub> induces a decomposition of ''A'' and ''B'' as described in the outline of the proof: | |||

:: <math> | |||

A_1 , \qquad | |||

A_2 := A \setminus A_1 , \qquad | |||

B_1 := f_\ast (A_1) , \qquad | |||

B_2 := B \setminus B_1 | |||

</math> | |||

: that has the desired properties. | |||

Revision as of 14:39, 23 September 2013

The Schröder-Bernstein theorem (sometimes Cantor-Schröder-Bernstein theorem) is a fundamental theorem of set theory.

Essentially, it states that if two sets are such that each one has at least as many elements as the other

then the two sets have equally many elements.

Though this assertion may seem obvious it needs a proof, and it is crucial for the definition of cardinality to make sense.

Remark: In analogy to this theorem the term Schröder-Bernstein property is used in other contexts to describe similar properties.

The Schröder-Bernstein theorem

Theorem. If for two sets A and B there are an injective function from A into B and an injective function from B into A then there is a bijective function from A onto B.

In terms of cardinal numbers this is equivalent to:

Corollary. If |A| ≤ |B| and |B| ≤ |A| then |A| = |B|.

Here |A| and |B| denote the cardinal numbers corresponding to the sets A and B.

The corollary shows that ≤ is a partial order for cardinal numbers.

(The order is indeed a linear order, but this aspect is not touched by the theorem

since the existence of injective functions between the two sets is assumed in its statement.)

Remark. It is of theoretical interest that the proof of the theorem does not depend on the Axiom of Choice.

History

As it is often the case in mathematics, the name of this theorem does not truly reflect its history. The traditional name "Schröder-Bernstein" is based on two proofs published independently in 1898. Cantor is often added because he first stated the theorem in 1895, while Schröder's name is often omitted because his proof turned out to be flawed while the name of the mathematician who first proved it is not connected with the theorem.

In reality, the history was more complicated:

- 1887 Richard Dedekind proves the theorem but does not publish it.

- 1895 Georg Cantor states the theorem in his first paper on set theory and transfinite numbers (as an easy consequence of the linear order of cardinal numbers which he was going to prove later).

- 1896 Ernst Schröder announces a proof (as a corollary of a more general statement).

- 1897 Felix Bernstein, a young student in Cantor's Seminar, presents his proof.

- 1897 After a visit by Bernstein, Dedekind independently proves it a second time.

- 1898 Bernstein's proof is published by Émile Borel in his book on functions. (Communicated by Cantor at the 1897 congress in Zürich.)

Both proofs of Dedekind are based on his famous memoir Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen? and derive it as a corollary of a proposition equivalent to statement C in Cantor's paper:

Cantor observed this property as early as 1882/83 during his studies in set theory and transfinite numbers and therefore (implicitly) relying on the Axiom of Choice.

Proof

The bijective function between the two sets can be explicitly constructed from the two injective functions given. Therefore the Axiom of Choice is not needed in the proof. (There are many versions of the proof.)

Outline

We denote by f the injective function from A to B, and by g the injective function from B to A.

The proof is based on a simple observation:

If A is the disjoint union of two sets, A1 and A2, and B the disjoint union of two sets, B1 and B2,

such that B1 is the image of A1 under f and A2 is the image of B2 under g

then a bijection from A onto B is obtained by taking f on A1 and g−1 on A2.

Such a dissection is characterized by the property that the following process, if performed on A1, gives A1 as a result. (Thus A1 is a fixed point.)

- Take a subset of A, find its image under f in B, take the complement, find its image under g in A, and, finally, take the complement.

This defines a mapping of subsets of A to subsets of A that is increasing, and such a mapping always has a fixed point.

Proof

By assumption, there are injective functions

They induce two (injective) image mappings between the power sets

The mapping

on the power set of A is monotone increasing

and

is a fixed point of σ

Thus the function h defined as

is a bijective function between A and B.

Details

(1) Recalling the definition of the image of a set under a function, the induced image mappings are

(2) σ is a monotone increasing function on the power set of A:

(3) Any monotone increasing function on a power set has a fixed point A1:

(4) h is well-defined and injective because f and g are injective and g−1 is defined on the complement of A1:

-

- Moreover, this also shows that h is bijective because it follows that the image of A under h is

- In other words, A1 induces a decomposition of A and B as described in the outline of the proof:

- that has the desired properties.