Tennessee (U.S. state): Difference between revisions

imported>Pat Palmer (adding when the state began) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) (removing unused ref) |

||

| (38 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{TOC|right}} | |||

{{dambigbox|Tennessee (U.S. state)|Tennessee}} | |||

{{Image|SE USA.jpg|right|350px|}} | {{Image|SE USA.jpg|right|350px|}} | ||

'''Tennessee''' is a state of | '''Tennessee''' is a landlocked state of southeast of the [[United States of America|United States]]. During colonial times (the 1700's), Tennessee was regarded as a western extension of the [[North Carolina (U.S. state)]] and [[South Carolina (U.S. state)|South Carolina]]. In 1796, Tennessee became the third state to join the union after the original thirteen colonies. In the [[American Civil War]] (1861-1865), Tennessee was one of the eleven states that seceded the United States to form the [[Confederate States of America]]. | ||

Tennessee is contiguous to eight other states in the southeast portion of the country. The state is crossed twice north-south by the [[Tennessee River]], dividing it into three parts (West, Middle and East Tennessee) that are geologically distinct. East Tennessee is mountainous (and includes part of the [[Appalachian Mountains]]). Middle Tennessee is a rugged plateau, and West Tennessee consists of many small rivers with swamps and rugged hills at a lower elevation. | |||

The state's major cities are [[Memphis, Tennessee|Memphis]] (southwest corner), [[Nashville, Tennessee|Nashville]] (the state capital, in the middle of the state), and in East Tennessee, [[Knoxville, Tennessee|Knoxville]] and [[Chattanooga, Tennessee|Chattanooga]]. | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| Line 14: | Line 20: | ||

Only the settlement north of the Holston was on land legally ceded by Indians; this area was governed by Virginia until 1779. The other settlers, who were on Indian land, set up their own government, called the Watauga Association, at first leasing the land from the Cherokees and finally purchasing it under the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in 1775. Under the same treaty, the North Carolina jurist Richard Henderson and his Transylvania Company purchased an immense tract of land in Kentucky and Middle Tennessee from the Cherokees. After Virginia nullified the company's title to Kentucky, Henderson and his associates sponsored the settlement of the Cumberland Valley in the vicinity of Nashville in 1779-1780. | Only the settlement north of the Holston was on land legally ceded by Indians; this area was governed by Virginia until 1779. The other settlers, who were on Indian land, set up their own government, called the Watauga Association, at first leasing the land from the Cherokees and finally purchasing it under the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in 1775. Under the same treaty, the North Carolina jurist Richard Henderson and his Transylvania Company purchased an immense tract of land in Kentucky and Middle Tennessee from the Cherokees. After Virginia nullified the company's title to Kentucky, Henderson and his associates sponsored the settlement of the Cumberland Valley in the vicinity of Nashville in 1779-1780. | ||

== | ===Before the Civil War=== | ||

===After the Civil War=== | |||

====Reconstruction Efforts==== | |||

The years after the Civil War were characterized by tension and unrest between blacks and former Confederates, the worst of which occurred in [[Memphis riots of 1866|Memphis in 1866]].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Ryan |first=James Gilbert |title=The Memphis Riots of 1866: Terror in a Black Community During Reconstruction |journal=The Journal of Negro History |date=July 1977 |volume=62 |issue=3 |pages=243–257 |doi=10.2307/2716953 |jstor=2716953 |publisher=The University of Chicago Press|s2cid=149765241 }}</ref> Because Tennessee had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment before its readmission to the Union, it was the only former secessionist state that did not have a military governor during [[Reconstruction Era|Reconstruction]].{{sfn|Corlew|Folmsbee|Mitchell|1981|pp=333–334}} The [[Radical Republicans]] seized control of the state government toward the end of the war, and appointed [[William G. Brownlow|William G. "Parson" Brownlow]] governor. Under Brownlow's administration from 1865 to 1869, the legislature allowed African American men to vote, disenfranchised former Confederates, and took action against the [[Ku Klux Klan]], which was founded in December 1865 in [[Pulaski, Tennessee|Pulaski]] as a vigilante group to advance former Confederates' interests.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Coulter |first1=E. Merton |author1-link=E. Merton Coulter |title=William G. Brownlow: Fighting Parson of the Southern Highlands |date=1999 |publisher=University of Tennessee Press |location=Knoxville, TN |isbn=978-1-57233-050-4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=egskEhcF5gkC |access-date=May 12, 2021 |via=Google Books}}</ref> In 1870, [[Southern Democrats]] regained control of the state legislature,{{sfn|Lamon|1980|pp=46-48}} and over the next two decades, passed [[Jim Crow laws]] to enforce [[racial segregation]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Folmsbee |first1=Stanley J. |title=The Origin of the First "Jim Crow" Law |journal=The Journal of Southern History |date=May 1949 |volume=15 |issue=2 |pages=235–247 |doi=10.2307/2197999 |jstor=2197999 |publisher=Southern Historical Association |location=Atlanta}}</ref> | |||

====Lynchings==== | |||

Between 1882 and 1940, Tennessee had 251 [[lynching]]s, with 47 white victims, and 204 African American victims.<ref name=lynching /> There exists an online catalog<ref name=lynchcatTN /> of the names/dates/locations of confirmed lynching victims in the state. During those years (1882-1940), annually an average of nearly one white person was lynched and about four black people were lynched. It is safe to say that blacks, and sometimes white people who befriended blacks, lived in fear of becoming a target themselves. The lynchings occurred mostly in West and Middle Tennessee, likely because these farming areas had a larger population of African Americans than mountainous East Tennessee. | |||

====Epidemics==== | |||

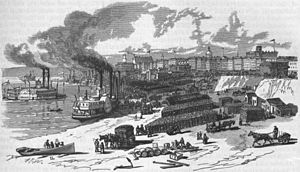

[[File:AmCyc Memphis (Tennessee).jpg|thumb|right|alt=1879 illustration of Memphis, showing the city's cotton industry|Memphis became known as the "Cotton Capital of the World" in the years following the Civil War]] | |||

A number of epidemics swept through Tennessee in the years after the Civil War, including [[cholera]] in 1873, which devastated the Nashville area,<ref>{{cite book|last=Barnes|first=Joseph K.|date=1875|title=The Cholera Epidemic of 1873 in the United States|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HwwPAAAAYAAJ|location=Washington, D.C.|publisher=U.S. Government Printing Office|page=478|author-link=Joseph Barnes (American physician)|access-date=May 23, 2021 |via=Google Books}}</ref> and [[yellow fever]] in 1878, which killed more than one-tenth of Memphis's residents.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Baker |first1=Thomas H. |title=Yellowjack: The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878 in Memphis, Tennessee |journal=Bulletin of the History of Medicine |date=May–June 1968 |volume=42 |issue=3 |pages=241–264 |jstor=44450733 |publisher=[[The Johns Hopkins University Press]] |location=Baltimore|pmid=4874077 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Webb |first1=Gina |title=Yellow fever epidemic changes course of Memphis history in 'Fever Season' |url=https://www.ajc.com/entertainment/yellow-fever-epidemic-changes-course-memphis-history-fever-season/IRFeaGgIt83vD2I8kgJ6WN/ |access-date=May 23, 2021 |work=The Atlanta Journal-Constitution |date=October 20, 2012}}</ref> Arriving with the dispersal of World War I troops back to their home countries, the so-called Spanish flu (which actually had nothing in particular to do with Spain) arrived in the U.S. in August 1918 and spread rapidly across the country within two months. Although the officially confirmed count of Tennessee deaths was less than 8000, this is a vast underestimation. Nearly 6000 were known to have died just in Chattanooga.<ref name=SFChat>[https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/world-war-i/ World War I (1914-1918)] by Margaret Ripley Wolfe, Tennessee Encyclopedia online.</ref> All the cities, and every rural town also, were hard hit.<ref name=SpanFluTN>[https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/influenza-pandemic-of-1918-19/ Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19] by Allen R. Coggins, Tennessee Encyclopedia online.</ref> Normal life was completely disrupted for a few months, with schools and all gathering places closed, and makeshift clinics for the sick hastily assembled. | |||

====Sharecroppers==== | |||

Despite New South promoters' efforts, agriculture continued to dominate Tennessee's economy.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=McKenzie |first1=Robert Tracy |title=Freedmen and the Soil in the Upper South: The Reorganization of Tennessee Agriculture, 1865-1880 |journal=The Journal of Southern History |date=February 1993 |volume=59 |issue=1 |pages=63–84 |doi=10.2307/2210348 |jstor=2210348 |publisher=Southern Historical Association |location=Atlanta}}</ref> The majority of freed slaves were forced into [[sharecropping]] during the latter 19th century, and many others worked as agricultural wage laborers.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Winters |first1=Donald L. |title=Postbellum Reorganization of Southern Agriculture: The Economics of Sharecropping in Tennessee |journal=Agricultural History |date=Autumn 1988 |volume=62 |issue=4 |pages=1–19 |jstor=3743372 |publisher=Agricultural History Society}}</ref> | |||

====Centennial==== | |||

In 1897, Tennessee celebrated its statehood centennial one year late with the [[Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition]] in Nashville.<ref>{{cite book |title=Official Guide To The Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition and City of Nashville |date=1897 |publisher=Marshall & Bruce |location=Nashville |url=https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/officialguidete00tenn |doi=10.5479/sil.999616.39088016962151 |access-date=May 23, 2021 |via=[[Smithsonian Libraries]]}}</ref> A [[Parthenon (Nashville)|full-scale replica]] of the [[Parthenon]] in [[Athens]] was designed by architect [[William Crawford Smith]] and constructed for the celebration, owing to the city's reputation as the "Athens of the South."{{sfn|Corlew|Folmsbee|Mitchell|1981|pp=411–414}}<ref>{{cite journal |last=Coleman |first=Christopher K. |title=From Monument to Museum: The Role of the Parthenon in the Culture of the New South |journal=Tennessee Historical Quarterly |volume=49 |issue=3 |page=140 |jstor=42626877 |date=Fall 1990}}</ref> | |||

====Industrialization and agriculture==== | |||

Reformers worked to modernize Tennessee into a "[[New South]]" economy during this time. With the help of Northern investors, Chattanooga became one of the first industrialized cities in the South.<ref name=jsh/> Memphis became known as the "Cotton Capital of the World" during the late 19th century, and Nashville, Knoxville, and several smaller cities saw modest industrialization.<ref name=jsh>{{cite journal|last=Belissary |first=Constantine G.|date=May 1953|title=The Rise of Industry and the Industrial Spirit in Tennessee, 1865-1885|jstor=2955013 |journal=The Journal of Southern History|volume=19|issue=2|pages=193–215|doi=10.2307/2955013}}</ref> Northerners also began exploiting the coal fields and mineral resources in the Appalachian Mountains. | |||

====Convict Leasing==== | |||

To pay off debts and alleviate overcrowded prisons, the state turned to [[convict leasing]], providing prisoners to mining companies as [[strikebreakers]], which was protested by miners forced to compete with the system.{{sfn|Corlew|Folmsbee|Mitchell|1981|pp=387–389}} An armed uprising in the Cumberland Mountains known as the [[Coal Creek War]] in 1891 and 1892 resulted in the state ending convict leasing.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Cotham |first1=Perry C. |title=Toil, Turmoil & Triumph: A Portrait of the Tennessee Labor Movement |date=1995 |publisher=Hillsboro Press |location=Franklin, Tennessee |isbn=9781881576648 |pages=56–80 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HWiN4VbNBLQC |access-date=May 23, 2021 |via=Google Books}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Shapiro |first1=Karin |title=A New South Rebellion: The Battle Against Convict Labor in the Tennessee Coalfields, 1871-1896 |date=1998 |publisher=[[University of North Carolina Press]] |location=Chapel Hill, North Carolina |isbn=9780807867051 |pages=75–102, 184–205 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nSE6DwAAQBAJ |access-date=May 23, 2021 |via=Google Books}}</ref> | |||

=== 1930 to the present === | |||

==See also== | |||

[[United States of America/Catalogs/States and Territories|U.S. States and Territories]] | |||

==Provenance== | |||

{{WPAttribution}} | |||

==References== | |||

<references> | |||

<ref name=lynching>[https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/lynching/ Lynching] by Kathy Bennett, Tennessee Encyclopedia. Last access 5/31/2023</ref> | |||

<ref name=lynchcatTN> | |||

[https://www.abhmuseum.org/tennessee-lynching-victims-memorial/ Tennessee Lynching Victims Memorial] on abhmuseum.org, last access 5/31/2023. | |||

</ref> | |||

</references> | |||

Revision as of 12:49, 1 July 2024

Tennessee is a landlocked state of southeast of the United States. During colonial times (the 1700's), Tennessee was regarded as a western extension of the North Carolina (U.S. state) and South Carolina. In 1796, Tennessee became the third state to join the union after the original thirteen colonies. In the American Civil War (1861-1865), Tennessee was one of the eleven states that seceded the United States to form the Confederate States of America.

Tennessee is contiguous to eight other states in the southeast portion of the country. The state is crossed twice north-south by the Tennessee River, dividing it into three parts (West, Middle and East Tennessee) that are geologically distinct. East Tennessee is mountainous (and includes part of the Appalachian Mountains). Middle Tennessee is a rugged plateau, and West Tennessee consists of many small rivers with swamps and rugged hills at a lower elevation.

The state's major cities are Memphis (southwest corner), Nashville (the state capital, in the middle of the state), and in East Tennessee, Knoxville and Chattanooga.

History

Pre 1780

Several Native American tribes occupied the area that would become Tennessee. The most prominent were the Cherokee in the east, the Chickasaw in the west, and the Shawnee and Yuchi in the middle region. The first Europeans to visit Tennessee probably were Spaniards, members of the expeditions of Hernando de Soto (1539-1544) and Juan Pardo (1566-1567). The Spanish built several small forts, but they did not colonize the area.

King Charles II of England included the Tennessee country in the Carolina grants of 1663 and 1665. The first Englishmen to visit the region came to East Tennessee in 1673. In the same year two Frenchmen, Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet, landed at the site of Memphis while on a voyage down the Mississippi River. In 1682, another French expedition, under Robert Cavelier, sieur de la Salle, built Fort Prud'homme at the mouth of the Hatchie River in what is now West Tennessee. This rivalry between the British and the French reached a climax in the French and Indian War, which ended in British victory and the withdrawal of the French.

American scouts, notably Daniel Boone, began exploring Tennessee looking for farmland; their first permanent settlement began about 1769. The settlers, coming mainly from the back country of Virginia and North Carolina, were dissatisfied with corrupt and oppressive features of the colonial governments; they were motivated by land hunger and a restless spirit. By 1772, there were four areas of American settlement: one between the forks of the Holston River, near Bristol; another along the Watauga River, in the vicinity of Elizabethton; a third west of the Holston River, near Rogersville; and a fourth along the Nolichucky River, near the present Erwin.

Only the settlement north of the Holston was on land legally ceded by Indians; this area was governed by Virginia until 1779. The other settlers, who were on Indian land, set up their own government, called the Watauga Association, at first leasing the land from the Cherokees and finally purchasing it under the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in 1775. Under the same treaty, the North Carolina jurist Richard Henderson and his Transylvania Company purchased an immense tract of land in Kentucky and Middle Tennessee from the Cherokees. After Virginia nullified the company's title to Kentucky, Henderson and his associates sponsored the settlement of the Cumberland Valley in the vicinity of Nashville in 1779-1780.

Before the Civil War

After the Civil War

Reconstruction Efforts

The years after the Civil War were characterized by tension and unrest between blacks and former Confederates, the worst of which occurred in Memphis in 1866.[1] Because Tennessee had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment before its readmission to the Union, it was the only former secessionist state that did not have a military governor during Reconstruction.Template:Sfn The Radical Republicans seized control of the state government toward the end of the war, and appointed William G. "Parson" Brownlow governor. Under Brownlow's administration from 1865 to 1869, the legislature allowed African American men to vote, disenfranchised former Confederates, and took action against the Ku Klux Klan, which was founded in December 1865 in Pulaski as a vigilante group to advance former Confederates' interests.[2] In 1870, Southern Democrats regained control of the state legislature,Template:Sfn and over the next two decades, passed Jim Crow laws to enforce racial segregation.[3]

Lynchings

Between 1882 and 1940, Tennessee had 251 lynchings, with 47 white victims, and 204 African American victims.[4] There exists an online catalog[5] of the names/dates/locations of confirmed lynching victims in the state. During those years (1882-1940), annually an average of nearly one white person was lynched and about four black people were lynched. It is safe to say that blacks, and sometimes white people who befriended blacks, lived in fear of becoming a target themselves. The lynchings occurred mostly in West and Middle Tennessee, likely because these farming areas had a larger population of African Americans than mountainous East Tennessee.

Epidemics

A number of epidemics swept through Tennessee in the years after the Civil War, including cholera in 1873, which devastated the Nashville area,[6] and yellow fever in 1878, which killed more than one-tenth of Memphis's residents.[7][8] Arriving with the dispersal of World War I troops back to their home countries, the so-called Spanish flu (which actually had nothing in particular to do with Spain) arrived in the U.S. in August 1918 and spread rapidly across the country within two months. Although the officially confirmed count of Tennessee deaths was less than 8000, this is a vast underestimation. Nearly 6000 were known to have died just in Chattanooga.[9] All the cities, and every rural town also, were hard hit.[10] Normal life was completely disrupted for a few months, with schools and all gathering places closed, and makeshift clinics for the sick hastily assembled.

Despite New South promoters' efforts, agriculture continued to dominate Tennessee's economy.[11] The majority of freed slaves were forced into sharecropping during the latter 19th century, and many others worked as agricultural wage laborers.[12]

Centennial

In 1897, Tennessee celebrated its statehood centennial one year late with the Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition in Nashville.[13] A full-scale replica of the Parthenon in Athens was designed by architect William Crawford Smith and constructed for the celebration, owing to the city's reputation as the "Athens of the South."Template:Sfn[14]

Industrialization and agriculture

Reformers worked to modernize Tennessee into a "New South" economy during this time. With the help of Northern investors, Chattanooga became one of the first industrialized cities in the South.[15] Memphis became known as the "Cotton Capital of the World" during the late 19th century, and Nashville, Knoxville, and several smaller cities saw modest industrialization.[15] Northerners also began exploiting the coal fields and mineral resources in the Appalachian Mountains.

Convict Leasing

To pay off debts and alleviate overcrowded prisons, the state turned to convict leasing, providing prisoners to mining companies as strikebreakers, which was protested by miners forced to compete with the system.Template:Sfn An armed uprising in the Cumberland Mountains known as the Coal Creek War in 1891 and 1892 resulted in the state ending convict leasing.[16][17]

1930 to the present

See also

Provenance

- Some content on this page may previously have appeared on Wikipedia.

References

- ↑ Ryan, James Gilbert (July 1977). "The Memphis Riots of 1866: Terror in a Black Community During Reconstruction". The Journal of Negro History 62 (3): 243–257. DOI:10.2307/2716953. Research Blogging.

- ↑ (1999) William G. Brownlow: Fighting Parson of the Southern Highlands. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-050-4.

- ↑ (May 1949) "The Origin of the First "Jim Crow" Law". The Journal of Southern History 15 (2): 235–247. DOI:10.2307/2197999. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Lynching by Kathy Bennett, Tennessee Encyclopedia. Last access 5/31/2023

- ↑ Tennessee Lynching Victims Memorial on abhmuseum.org, last access 5/31/2023.

- ↑ Barnes, Joseph K. (1875). The Cholera Epidemic of 1873 in the United States. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ (May–June 1968) "Yellowjack: The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878 in Memphis, Tennessee". Bulletin of the History of Medicine 42 (3): 241–264. PMID 4874077.

- ↑ Yellow fever epidemic changes course of Memphis history in 'Fever Season', The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 20, 2012.

- ↑ World War I (1914-1918) by Margaret Ripley Wolfe, Tennessee Encyclopedia online.

- ↑ Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19 by Allen R. Coggins, Tennessee Encyclopedia online.

- ↑ (February 1993) "Freedmen and the Soil in the Upper South: The Reorganization of Tennessee Agriculture, 1865-1880". The Journal of Southern History 59 (1): 63–84. DOI:10.2307/2210348. Research Blogging.

- ↑ (Autumn 1988) "Postbellum Reorganization of Southern Agriculture: The Economics of Sharecropping in Tennessee". Agricultural History 62 (4): 1–19.

- ↑ (1897) Official Guide To The Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition and City of Nashville. Nashville: Marshall & Bruce. DOI:10.5479/sil.999616.39088016962151.

- ↑ Coleman, Christopher K. (Fall 1990). "From Monument to Museum: The Role of the Parthenon in the Culture of the New South". Tennessee Historical Quarterly 49 (3).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Belissary, Constantine G. (May 1953). "The Rise of Industry and the Industrial Spirit in Tennessee, 1865-1885". The Journal of Southern History 19 (2): 193–215. DOI:10.2307/2955013. Research Blogging.

- ↑ (1995) Toil, Turmoil & Triumph: A Portrait of the Tennessee Labor Movement. Franklin, Tennessee: Hillsboro Press, 56–80. ISBN 9781881576648.

- ↑ (1998) A New South Rebellion: The Battle Against Convict Labor in the Tennessee Coalfields, 1871-1896. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 75–102, 184–205. ISBN 9780807867051.