American Civil War: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen (import from Wiki (much by RJ)) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) (adding some links to the lede) |

||

| (141 intermediate revisions by 32 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | |||

{{Image|Civil war map.png|right|350px|Map depicting slave and free states during the war.}} | |||

The '''Civil War''' (1861-65), between the '''[[United States of America|U.S.A.]]''' and eleven Southern states that attempted to form a new nation, had a death toll of over 600,000 lives that exceeded all other wars the U.S. has ever engaged in. The war began over tensions about whether slaves escaping into non-slave stated had to be captured and extradited to their origin state, and whether new territories would allow slavery to be legal. The Union (U.S. government) eventually defeated the rebelling [[Confederate States of America|Confederacy]], and slavery was abolished everywhere in the U.S.. | |||

{{ | {{TOC|right}} | ||

== Outline of the war == | |||

The war began because southern secessionists had come to the conclusion that their way of life was threatened by the elected Republican national majority. Prior to the war, the South had enjoyed for a time legislative majorities in both houses, routine victories in the presidential elections, and control of the Supreme Court. By 1860, because of changes brought by the market and transportation revolutions, immigration, and industrialization, Northern states had routinely maintained their electoral majorities in both houses. In 1854, the [[Republican Party (United States), history |Republican Party]] was formed. It was pledged to halting the further expansion of slavery. And by 1860, the Republican Party, solely on the strength of the electoral power of the Northern states elected [[Abraham Lincoln]] president. With their complete loss of power in the national government to a party hostile to the institution through which white southerners derived their identity (slavery), seven states from the deep south formed the [[Confederate States of America]] and proclaimed their independence from the United States. (see the [[Secession Crisis]]) | |||

Fighting began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces attacked a small U.S. military installation at [[Fort Sumter]] in Charleston, South Carolina. Lincoln called for an invasion force to recapture the fort. Four more states seceded. These states were from the upper south, and they rejected Lincoln's coercion and felt that their political future lay more closely with the Confederacy than with the Union. With their inclusion, the Confederacy had eleven states in all. | |||

During the first year, the Union asserted control of the border states and established a [[Union Blockade|naval blockade]], as a means of [[economic warfare]] rather than stopping military reinforcements, as both sides raised large armies. In 1862 large, bloody battles began, causing massive casualties as both sides fought heroically. In September 1862, Lincoln's [[Emancipation Proclamation]] made the freeing of slaves in the South a war goal, so as to ruin the economic base of the Confederacy, despite opposition from northern [[Copperheads]] who tolerated secession and slavery. [[War Democrats]] reluctantly accepted emancipation as part of total war needed to save the Union. Emancipation ended the likelihood of intervention from Britain and France on behalf of the Confederacy. Emancipation allowed the Union to recruit 190,000 blacks (both free and ex-slave) for reinforcements, a resource that the Confederacy did not dare exploit until it was too late. | |||

In the East in 1862, Confederate general [[Robert E. Lee]] assumed command of the [[Army of Northern Virginia]] and rolled up a series of victories over the [[Army of the Potomac]], but his best General, [[Stonewall Jackson|Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson]], was killed at the [[Battle of Chancellorsville]] in May 1863. Lee's invasion of the North was repulsed at the [[Battle of Gettysburg]] in Pennsylvania in July 1863; he barely managed to escape back to Virginia. The [[United States Navy|Union Navy]] captured the port of New Orleans in 1862, and [[Ulysses S. Grant]] seized control of the [[Mississippi River]] by defeating multiple uncoordinated Confederate armies and capturing [[Battle of Vicksburg|Vicksburg, Mississippi]] in July 1863, thus splitting the Confederacy. | |||

By 1864, long-term Union advantages in geography, manpower, industry, finance, political organization and transportation were overwhelming the Confederacy. Grant fought a remarkable series of bloody battles with Lee in Virginia in the summer of 1864. Lee's defensive tactics resulted in higher casualties for Grant's army, but Lee lost strategically overall as he could not replace his casualties and was forced to retreat into trenches around his capital, Richmond, Virginia. Meanwhile, in the West, [[William Tecumseh Sherman]] captured Atlanta, Georgia. [[Sherman's March to the Sea]] destroyed a hundred-mile-wide swath of Georgia. In 1865, the Confederacy collapsed after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House; all slaves in the Confederacy were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. Slaves in the border states and Union controlled parts of the South were freed by state action or by the [[Thirteenth Amendment]]. | |||

The full restoration of the Union was the work of a highly contentious postwar era known as [[Reconstruction]] (1863-1877). The war produced about 970,000 military casualties (3% of the population), including approximately 620,000 soldier deaths—two-thirds by disease, making it the deadliest war in American history in terms of American losses. Slavery and state's rights were the main causes, but the nuances continue to be debated, along with the reasons for Union victory, and even the name of the war itself.<ref> For a century afterwards southerners called it the "war between the states." The official Union name was the "War of the Rebellion."</ref> The main results of the war were the restoration and strengthening of the Union, and the end of [[slavery]] in the United States. The South became much poorer than the rest of the U.S. for a century. | |||

== | ==Causes of the War== | ||

''Main article: [[U.S. Civil War, Origins]]'' | |||

The direct cause of the Civil War was that the Union refused to allow any state to break away without permission of Congress, so to understand the cause of the War depends on understanding the causes of secession. Basically, the South became alienated from the nation, arguing that it was being treated as an inferior, in violation of the letter and the spirit of the Constitution. The maltreatment always involved issues of slavery --the North was increasingly hostile to slavery and the South held that slavery was an integral part of the social, economic and constitutional system. A serious threat to slavery meant that South had to be an independent nation. As the North was growing faster, and thus gaining in political power and electoral votes, Southerners realized by 1860 it was now or never to split away, and the election of Lincoln gave them reason. | |||

The inferior treatment was primarily because of slavery, which had been abolished in the North, flourished in the deep South, and was alive but weak in the border states. The new Republican party, founded in 1854, was committed to stopping the expansion of slavery, so that it would be contained and eventually die away. As Lincoln said in his 1858 "House Divided Speech", Republicans wanted to "arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction". Much of the political battle in the 1850s focused on the expansion of slavery into the newly created territories. Both North and South assumed that if slavery could not expand it would wither and die. | |||

Southern fears of losing control of the federal government to antislavery forces, and Northern fears that the [[slave power]] already controlled the government, brought the crisis to a head in the late 1850s. Sectional disagreements over the morality of slavery, the scope of democracy and the economic merits of free labor vs. slave plantations caused the [[Whig Party]] and "[[Know Nothing]]" parties to collapse, and new ones to arise: (the [[Free Soil Party]] in 1848, the [[Republican Party (United States), history |Republicans]] in 1854, the [[Constitutional Union Party]] in 1860). In 1860, the last remaining national political party, the [[Democratic Party (United States), history|Democratic Party]], split along sectional lines. | |||

Other dimensions of the slavery debate included the threat that abolitionist would stir up large-scale slave revolts, as indeed was attempted by [[John Brown]] in 1859. Modernization was a factor, as the South was locked into a traditional economy with most of its investment money going into slaves and land, while the North invested in machinery, infrastructure and education. States Rights was a way to phrase the issue in Constitutional terms. Economic issues united the North and South more than it split it. The business community opposed war. Tariff issues were debated at length, but were not a cause of secession because the South wrote the tariffs to its advantage--most recently in 1857. The overseas expansion of slavery was debated, as a brief, failed effort was made to purchase Cuba, which already had slavery. (Spain refused to sell. See [[Ostend Manifesto]] of 1854) | |||

Earlier, the debate over annexation of Texas in 1844-45 saw antislavery elements in the North angered as they felt the country was dragged into war for the benefit of slavery expansion. | |||

Politicians attempted numerous compromises to head off the growing threat of disunion. The [[Compromise of 1820]] kept the equal political balance in the Senate by admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state. The | |||

[[Compromise of 1850]] resolved the problems created by annexation of new territory in Texas, New Mexico and California. However it also produced a stronger [[Fugitive Slave Law]] that forced northern law officials to seize and return runaway slaves. Antislavery sentiment was excited by the runaway success of the novel and play ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'', by [[Harriet Beecher Stowe]], which focused on the heroic efforts of a slave to run away from cruel treatment by Simon Legree.<ref> In reality fewer than 1000 slaves a year succeeded in escaping the South, out of 4 million slaves.</ref> | |||

Senator [[Stephen A. Douglas]], the most powerful Democrat in the 1850s, had been the chief sponsor of the Compromise of 1850. In 1854 he suddenly reversed himself and proclaimed "popular sovereignty", whereby people democratically would make the basic decisions. Douglas passed the extremely controversial [[Kansas Nebraska Act]] that opened Kansas up to settlers who would choose to make it a free state or a slave state. Instead of a flowering of democracy the result was a bloody small-scale civil war in Kansas as both sides supported and armed their own settlers. The Republican party formed as a result, and the Democratic party was ripped apart. | |||

The polarizing effect of slavery split the largest religious denominations (the Methodist, Baptist and Presbyterian churches) the worst cruelties of slavery (whippings, mutilations and families split apart) raised abolitionist attacks. | |||

By 1860 the Southerns were developing a sense of nationalism and apartness, and had broken most of the cultural, religious and political ties with the North. Only business ties remained, and the Union itself. Southern separatists insisted the South had all the makings of a great, strong, rich nation. They though "Cotton is King!"--that is the Southern monopoly of raw cotton would force British and European industrialists to support southern independence. What they did not realize was that American nationalism was also growing in the North, and would not tolerate disruption of the Union. | |||

In 1860 neither civil rights nor voting rights for blacks were stated as goals by the North; they became important only later, during [[Reconstruction]]. The Republican party sought the long-term end of slavery, by blocking its expansion and by the superiority of free labor as more productive and profitable. Immediate emancipation was the goal of only a small number of abolitionists, who had little or no real power in the 1850s, although Southerners greatly exaggerated their influence. | |||

===States' rights=== | |||

Questions such as whether the Union was older than the states or the other way around fueled the debate over states' rights. Whether the federal government was supposed to have substantial powers or whether it was merely a voluntary federation of sovereign states added to the controversy. According to historian Kenneth M. Stampp, each section used states' rights arguments when convenient, and shifted positions when convenient.<ref>Stampp, ''Causes of the Civil War,'' page 59</ref> | |||

Southerners argued that States Rights meant the federal government was strictly limited and could not abridge the rights of states, and so had no power to prevent slaves from being carried into new territories. States' rights advocates also cited the Constitution's fugitive slave clause to demand federal jurisdiction over slaves who escaped into the North. The South's leading theorist [[John C. Calhoun]] regarded the territories as the "common property" of sovereign states, and said that Congress was acting merely as the "joint agents" of the states.<ref>McPherson, ''Battle Cry,'' page 57</ref> | |||

Before 1860, all presidents (except John Quincy Adams) were either Southern or pro-South on slavery questions. Lincoln's election changed that and the North's growing population implied northern control of future presidential elections. The South as a minority had special rights, said Calhoun, for, he explained, "Governments were formed to protect minorities, for majorities could take care of themselves".<ref> Allan Nevins, ''Ordeal of the Union: Fruits of Manifest Destiny 1847-1852,'' 1:155</ref> Jefferson Davis,calling on the traditions of [[Republicanism, U.S.|republicanism]] said the fight for "liberty" against "the tyranny of an unbridled majority" gave the southern states a right to secede.<ref>Jefferson Davis' "Second Inaugural Address" Feb. 22, 1862 in Dunbar Rowland, ed., ''Jefferson Davis, Constitutionalist,'' 5:198-203. </ref> | |||

The Supreme Court decision of 1857 in [[Dred Scott v. Sandford|''Dred Scott v. Sandford'']] tried to resolve the slavery question but instead inflamed the North and escalated tensions. [[Roger Taney|Chief Justice Roger B. Taney's]] decision said that slaves were "so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect",<ref>David Potter, ''The Impending Crisis'', p 275</ref> and that slaves could be taken to free states and territories. Lincoln warned that "the next ''Dred Scott'' decision" could threaten northern states with slavery.<ref>First Lincoln Douglas Debate at Ottawa, Illinois August 21, 1858</ref> | |||

The | |||

====Slavery as a cause of the war==== | |||

As historian Allan Nevins explained, "As the fifties wore on, an exhaustive, exacerbating and essentially futile conflict over slavery raged to the exclusion of nearly all other topics."<ref>Nevins, ''Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847-1852'', page 163</ref> Lincoln said in 1860, "this question of Slavery was more important than any other; indeed, so much more important has it become that no other national question can even get a hearing just at present."<ref>Abraham Lincoln, Speech at New Haven, Conn., March 6, 1860</ref> | |||

The | The plantation owners in the 1860 election generally voted for the more moderate Constitutional Union party, which rejected secession. After the election, however, most planters changed and supported secession. Thus there was a strong correlation between the number of plantations in a region and the degree of support for secession. The states of the deep south had the greatest concentration of plantations and were the first to secede. The upper South slave states of Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee had fewer plantations and rejected secession until the [[Battle of Fort Sumter|Fort Sumter]] crisis forced them to choose sides. Border states had fewer plantations still and never seceded.<ref>McPherson, ''Battle Cry of Freedom'' p 242, 255, 282-3. Maps on page 101 (The Southern Economy) and page 236 (The Progress of Secession) are also relevant</ref> | ||

In 1861 secession replaced slavery as the defining issue, as 8 slave states refused to join the original seven Confederate states until Lincoln called for volunteers to invade South Carolina in April, when 4 more joined. Lincoln made a deliberate effort to mollify the slave-owners in the border states (offering to buy their slaves for cash), to keep them from supporting the enemy. They rejected the offers, however. The North rallied in spring 1861 against secession, and the attack on the national flag at Ft. Sumter, not against slavery as such. Thus Ulysses S. Grant (who had recently owned a slave himself), rallied to the flag and raised troops to fight. By 1862, most northerners were coming to the position that slavery was so critical to the Confederacy that its abolition would speed the collapse of the rebellion. | |||

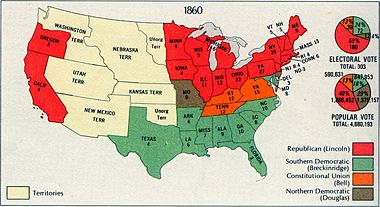

{{Image|US Presidential election 1960.jpg|right|380px|election of 1860}} | |||

===Rejection of compromise=== | ===Rejection of compromise=== | ||

Until | Until December 20, 1860, the political system had always successfully handled inter-regional crises. All but one crisis involved slavery, starting with debates on the three-fifths clause in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Congress had solved the crisis over the admission of Missouri as a slave state in 1819-21, the controversy over South Carolina's nullification of the tariff in 1832, the acquisition of [[Texas (U.S. state)|Texas]] in 1845, and the status of slavery in the territory acquired from Mexico in 1850.<ref> William E. Gienapp, "The Crisis of American Democracy: The Political System and the Coming of the Civil War." in Boritt ed. ''Why the Civil War Came'' 79-123</ref> | ||

However, in 1854, the old [[Second Party System]] broke down after passage of the [[Kansas Nebraska Act]]. The [[Whig Party (United States)|Whig Party]] disappeared, and the new [[Republican Party (United States), history |Republican Party]] arose in its place. It was the nation's first major party with only sectional appeal and a commitment to stop the expansion of slavery. | |||

Republican leader Senator Charles Sumner was violently attacked at his desk in the Senate by Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina, violating the sanctuary of Congress and emphasizing the increased resort to violence. Sumner recovered and became a dominant force in the Senate during the war and Reconstruction. | |||

Open warfare in the [[Kansas Territory]] ("[[Bleeding Kansas]]"), the [[Dred Scott v. Sandford|''Dred Scott'' decision]] of 1857, [[John Brown (abolitionist)|John Brown's raid]] in 1859 and the split in the [[U. S. Democratic Party, history |Democratic Party]] in 1860 polarized the nation between North and South. The election of Lincoln in 1860 was the final trigger for secession for the deep South Cotton states. During the secession crisis, many sought compromise—of these attempts, the best known was the "[[Crittenden Compromise]]"—but all failed. | |||

[[ | |||

===Economics=== | ===Economics=== | ||

Historians generally agree that economic conflicts were not a major cause of the war. Economic historian Lee A. Craig | Historians generally agree that economic conflicts were not a major cause of the war. Economic historian Lee A. Craig wrote in 1996 that "numerous studies by economic historians over the past several decades reveal that economic conflict was not an inherent condition of North-South relations during the antebellum era and did not cause the Civil War."<ref>Lee A. Craig in Woodworth, ed., ''The American Civil War: A Handbook of Literature and Research'' (1996), 505.</ref> Even Americans at the time understood how insignificant economic differences were in the secession crisis. This is evident in the exertions of numerous groups which tried during the 1860-61 winter to find a compromise and avert war. They did not turn to economic policies as a means to avert war. Except for slavery, which in the American context was mostly a cultural and social institution and only partially an economic institution, economics played no significant role as a cause for the Civil War. | ||

====Regional economic differences==== | ====Regional economic differences==== | ||

The South, Midwest, and Northeast had quite different economic structures. They traded with each other and each became more prosperous by staying in the Union, a point many businessmen made in 1860-61. However [[Charles Beard]] in the 1920s made a highly influential argument to the effect that these differences caused the war (rather than slavery or constitutional debates). He saw the industrial Northeast forming a coalition with the agrarian Midwest against the Plantation South. | The South, Midwest, and Northeast had quite different economic structures. They traded with each other and each became more prosperous by staying in the Union, a point many businessmen made in 1860-61. However, [[Charles Beard]] in the 1920s made a highly influential argument to the effect that these differences caused the war (rather than slavery or constitutional debates). He saw the industrial Northeast forming a coalition with the agrarian Midwest against the Plantation South. Beard's critics pointed out that his image of a unified Northeast was incorrect because the region was highly diverse with many different competing economic interests. In 1860-61, most business interests in the Northeast opposed war. After 1950, only a few mainstream historians accepted the Beard interpretation, though it was accepted by libertarian economists.<ref>Woodworth, ed. ''The American Civil War: A Handbook of Literature and Research'' (1996), 145, 151, 505, 512, 554, 557, and 684; Richard Hofstadter, ''The Progressive Historians: Turner, Beard, Parrington'' (1969); for one dissenter, see Marc Egnal, "The Beards Were Right: Parties in the North, 1840-1860," ''Civil War History'' 47, no. 1. (2001): 30-56.</ref>As Historian Kenneth Stampp—who abandoned Beardianism after 1950&mdashsummed up the scholarly consensus: "Most historians ... now see no compelling reason why the divergent economies of the North and South should have led to disunion and civil war; rather, they find stronger practical reasons why the sections, whose economies neatly complemented one another, should have found it advantageous to remain united."<ref>Kenneth M. Stampp, ''The Imperiled Union: Essays on the Background of the Civil War'' (1981), 198. Here's the full passage: | ||

Most historians...now see no compelling reason why the divergent economies of the North and South should have led to disunion and civil war; rather, they find stronger practical reasons why the sections, whose economies neatly complemented one another, should have found it advantageous to remain united. Beard oversimplified the controversies relating to federal economic policy, for neither section unanimously supported or opposed measures such as the protective tariff, appropriations for internal improvements, or the creation of a national banking system.... During the 1850s, Federal economic policy gave no substantial cause for southern disaffection, for policy was largely determined by pro-Southern Congresses and administrations. Finally, the characteristic posture of the conservative northeastern business community was far from anti-Southern. Most merchants, bankers, and manufacturers were outspoken in their hostility to antislavery agitation and eager for sectional compromise in order to maintain their profitable business connections with the South. The conclusion seems inescapable that if economic differences, real though they were, had been all that troubled relations between North and South, there would be no substantial basis for the idea of an irrepressible conflict.</blockquote></ref> | <blockquote>Most historians ... now see no compelling reason why the divergent economies of the North and South should have led to disunion and civil war; rather, they find stronger practical reasons why the sections, whose economies neatly complemented one another, should have found it advantageous to remain united. Beard oversimplified the controversies relating to federal economic policy, for neither section unanimously supported or opposed measures such as the protective tariff, appropriations for internal improvements, or the creation of a national banking system .... During the 1850s, Federal economic policy gave no substantial cause for southern disaffection, for policy was largely determined by pro-Southern Congresses and administrations. Finally, the characteristic posture of the conservative northeastern business community was far from anti-Southern. Most merchants, bankers, and manufacturers were outspoken in their hostility to antislavery agitation and eager for sectional compromise in order to maintain their profitable business connections with the South. The conclusion seems inescapable that if economic differences, real though they were, had been all that troubled relations between North and South, there would be no substantial basis for the idea of an irrepressible conflict.</blockquote></ref> | ||

====Free labor vs. pro-slavery arguments==== | ====Free labor vs. pro-slavery arguments==== | ||

Historian | Historian Eric Foner has argued that a free-labor ideology (which emphasized economic opportunity) dominated thinking in the North. By contrast, Southerners described free labor as "greasy mechanics, filthy operators, small-fisted farmers, and moonstruck theorists".<ref>James McPherson, "Antebellum Southern Exceptionalism: A New Look at an Old Question," ''Civil War History'' 50, No. 4 (December 2004), 421.</ref> They strongly opposed the homestead laws that were proposed to give free farms in the west, fearing the small farmers would oppose plantation slavery. Indeed, opposition to homestead laws was far more common in [[Secessionist#Confederate States of America|secessionist]] rhetoric than opposition to tariffs.<ref>Richard Hofstadter, "The Tariff Issue on the Eve of the Civil War", ''The American Historical Review'' Vol. 44, No. 1 (1938), 50-55 [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-8762%28193810%2944%3A1%3C50%3ATTIOTE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-B full text in JSTOR]</ref> Southerners such as Calhoun argued that slavery was "a positive good", and that slaves were more civilized and morally and intellectually improved because of slavery.<ref>John C. Calhoun, "[http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=71 Slavery a Positive Good]," February 6, 1837.</ref> | ||

History | |||

Southerners such as Calhoun argued that slavery was "a positive good", and that slaves were more civilized and morally and intellectually improved because of slavery.<ref>John Calhoun, | |||

In a broader sense, the North was rapidly modernizing in a manner deeply threatening to the South. The North was not only becoming more economically powerful, but it was also developing new modern, urban values. As James McPherson argues, "The ascension to power of the Republican Party, with its ideology of competitive, egalitarian free-labor capitalism, was a signal to the South that the Northern majority had turned irrevocably towards this frightening, revolutionary future."<ref>James McPherson, "Antebellum Southern Exceptionalism: A New Look at an Old Question," ''Civil War History'' 29 (Sept. 1983)</ref> The South, on the other hand, was clinging more and more to the old, rural traditional values of the Jeffersonian yeoman.<ref>J. Mills Thornton III, ''Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860'' (1978)</ref> And while the slave-owning elite were, relatively speaking, the most modern people in the South, the poor and middling whites who owned few or no slaves were the most beholden to the traditionalist values. This poor & middle class, called the [[Plain Folk of the Old South]], supported secession and war because they supported states' rights and feared the impact of freed slaves on their own prospects.<ref>J. Mills Thornton III, ''Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860'' (1978); Samuel C. Hyde Jr., "Plain Folk Reconsidered: Historiographical Ambiguity in Search of Definition" ''Journal of Southern History'' 71, no. 4 (November 2005).</ref> | |||

==Secession begins== | ==Secession begins== | ||

===Secession winter=== | ===Secession winter=== | ||

Before Lincoln took office, seven states declared their secession from the Union, and established a Southern government, the | Before Lincoln took office, seven states declared their secession from the Union, and established a Southern government, the Confederate States of America, on February 9, 1861. They took control of federal forts and other properties within their boundaries, with little resistance from President Buchanan, whose term ended on March 3, 1861. Buchanan asserted, "The South has no right to secede, but I have no power to prevent them." One quarter of the U.S. Army—the entire garrison in Texas—was surrendered to state forces by its commanding general, David E. Twiggs, who then joined the Confederacy. Secession allowed the North to pass bills for projects that had been blocked by Southern Senators before the war, including the [[Morrill Tariff]], land grant colleges (the [[Morrill Act]]), a [[Homestead Act]], a trans-continental railroad (the [[Pacific Railway Acts]]) and the [[National Banking Acts]]. | ||

===The Confederacy=== | ===The Confederacy=== | ||

{{main|Confederate States of America}} | {{main|Confederate States of America}} | ||

Seven [[Deep South]] cotton states seceded by February 1861, starting with [[South Carolina]], [[Mississippi]], [[Florida]], [[Alabama]], [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]], [[Louisiana]], and [[Texas]]. These seven states formed the [[Confederate States of America]] ( | Seven [[Deep South]] cotton states seceded by February 1861, starting with [[South Carolina (U.S. state)|South Carolina]], [[Mississippi (U.S. state)|Mississippi]], [[Florida (U.S. state)|Florida]], [[Alabama (U.S. state)]], [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]], [[Louisiana (U.S. state)|Louisiana]], and [[Texas (U.S. state)|Texas]]. These seven states formed the [[Confederate States of America]] (February 4, 1861), with [[Jefferson Davis]] as president, and a [[Confederate States Constitution|governmental structure]] closely modeled on the [[U.S. Constitution]]. In April and May 1861, four more slave states seceded and joined the Confederacy: [[Arkansas (U.S. state)]], [[Tennessee (U.S. state)|Tennessee]], [[North Carolina (U.S. state)]] and [[Virginia (U.S. state)|Virginia]]. Virginia was split in two, with the larger eastern portion of that state seceding to the Confederacy and the northwestern part breaking away to join the Union as the new state of [[West Virginia (U.S. state)|West Virginia]] in 1863.<ref> The Union recognized a rump Virginia government headed by Governor Edwards Pierrepont; it approved the secession of West Virginia.</ref> | ||

===The Union states=== | ===The Union states=== | ||

There were 23 states that remained loyal to the Union during the war: California, Connecticut, Delaware (slave), Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky (slave), Maine, Maryland (slave), Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri (slave), New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin. During the war, Nevada and West Virginia (slave) joined as new states of the Union. Most of Tennessee (slave) and Louisiana (slave) came under to Union control early in the war. | |||

There were 23 states that remained loyal to the Union during the war: | |||

The territories of | The territories of Colorado Territory, Dakota Territory, Nebraska Territory, Nevada Territory, New Mexico Territory (slave), Utah Territory, and Washington Territory fought on the Union side. Several slave-holding Native American tribes supported the Confederacy, giving the Indian territory (now Oklahoma) its own full-scale bloody civil war. | ||

===Border states=== | ===Border states=== | ||

The Border states in the Union were West Virginia (slave) (which broke away from Virginia and became a separate state), and four of the five northernmost slave states (Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky). | |||

The | |||

Maryland had numerous pro-Confederate officials who tolerated anti-Union rioting in Baltimore and the burning of bridges. Lincoln responded with [[martial law]] and called for troops. Militia units that had been drilling in the North rushed toward Washington and Baltimore.<ref>McPherson, ''Battle Cry,'' pages 284-287</ref> Before the Confederate government realized what was happening, Lincoln had seized firm control of Maryland (and the separate District of Columbia), by arresting Confederate leaders and holding them without trial for several months. | |||

In Missouri, an elected convention on secession voted decisively to remain within the Union. When pro-Confederate Governor Claiborne F. Jackson called out the state militia, it was attacked by federal forces under General Nathaniel Lyon, who chased the governor and the rest of the State Guard to the southwestern corner of the state. In the resulting vacuum the convention on secession reconvened and took power as the Unionist provisional government of Missouri. | |||

Kentucky did not secede; for a time, it declared itself neutral. However, the Confederates broke the neutrality by seizing the town of Columbus, Kentucky in September 1861. That turned opinion against the Confederacy, and the state reaffirmed its loyal status, while trying to maintain slavery. During a brief invasion by Confederate forces, Confederate sympathizers organized a secession convention, inaugurated a governor, and gained recognition from the Confederacy. The rebel government soon went into exile and never controlled the state. | |||

Counties in the northwestern portion of Virginia opposed secession and formed a pro-Union government shortly after Richmond's secession in 1861. Unlike the remainder of Virginia, residents in this mountainous region were poor subsistence farmers. These counties were admitted to the Union in 1863 as [[West Virginia (U.S. state)|West Virginia]]. Similar secessions appeared in [[East Tennessee]], but were suppressed by the Confederacy. Jefferson Davis arrested over 3,000 men suspected of being loyal to the Union and held them without trial.<ref>Mark Neely, ''Confederate Bastille: Jefferson Davis and Civil Liberties'' 1993 p. 10-11</ref> | |||

[[ | Noel Fisher describes the internal civil war and partisan violence that raged throughout the border states, especially in the mountain areas:<ref> Noel Fisher, " Feelin' Mighty Southern: Recent Scholarship on Southern Appalachia in the Civil War" ''Civil War History'' Volume: 47#4. 2001. pp 334+. </ref> | ||

:Loyalists, secessionists, deserters, and men with little loyalty to either side formed organized bands, fought each other as well as occupying troops, terrorized the population, and spread fear, chaos, and destruction. Military forces stationed in the Appalachian regions, whether regular troops or home guards, frequently resorted to extreme methods, including executing partisans summarily, destroying the homes of suspected bushwhackers, and torturing families to gain information. This epidemic of violence created a widespread sense of insecurity, forced hundreds of residents to flee, and contributed to the region's economic distress, demoralization, and division. | |||

Some 10,000 military engagements took place during the war, 40% of them in Virginia and Tennessee.<ref> Gabor Boritt, ed. ''War Comes Again'' (1995) p 247</ref> Separate articles deal with every major battle and some minor ones. This article only gives the broad outline | ==Phases== | ||

{{Image|USA CSA uniforms and insignia.jpg|right|350px|Uniforms of officers and enlisted men in the United States and Confederate armies.}} | |||

Some 10,000 military engagements took place during the war, 40% of them in Virginia and Tennessee.<ref> Gabor Boritt, ed. ''War Comes Again'' (1995) p 247</ref> Separate articles deal with every major battle and some minor ones. This article only gives the broad outline. | |||

===The war begins=== | ===The war begins=== | ||

Lincoln's victory in the election triggered South Carolina's declaration of secession from the Union. By February 1861, six more Southern states made similar declarations. On February 7, the seven states adopted a provisional constitution for the Confederate States of America and established their temporary capital at [[Montgomery, Alabama]]. A pre-war February [[peace conference of 1861]] met in Washington in a failed attempt at resolving the crisis. The remaining eight slave states rejected pleas to join the Confederacy. Confederate forces seized all but three Federal forts within their boundaries (they did not take Fort Sumter); President Buchanan protested but made no military response aside from a failed attempt to resupply Fort Sumter via the ship [[Star of the West]] (the ship was fired upon by Citadel cadets), and no serious military preparations. However, governors in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania quietly began buying weapons and training militia units. | |||

Lincoln's victory in the | |||

On | On March 4 1861, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as President. In his [[Inauguration|inaugural address]], he argued that the Constitution was a [[Preamble to the United States Constitution|''more perfect union'']] than the earlier [[Articles of Confederation|Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union]], that it was a binding contract, and called any secession "legally void". He stated he had no intent to invade Southern states, nor did he intend to end slavery where it existed, but that he would use force to maintain possession of federal property. His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union.<ref>Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861</ref> | ||

The South sent delegations to Washington and offered to pay for the federal properties and enter into a peace treaty with the United States. Lincoln rejected any negotiations with Confederate agents on the grounds that the Confederacy was not a legitimate government, and that making any treaty with it would be tantamount to recognition of it as a sovereign government. | The South sent delegations to Washington and offered to pay for the federal properties and enter into a peace treaty with the United States. Lincoln rejected any negotiations with Confederate agents on the grounds that the Confederacy was not a legitimate government, and that making any treaty with it would be tantamount to recognition of it as a sovereign government. | ||

[[Fort Sumter]] in Charleston, South Carolina, was one of the three remaining Union-held forts in the Confederacy, and Lincoln was determined to hold it. Under orders from Confederate President | [[Fort Sumter]] in Charleston, South Carolina, was one of the three remaining Union-held forts in the Confederacy, and Lincoln was determined to hold it. Under orders from Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Confederate soldiers under General P.T.G. Beauregard bombarded the fort with artillery on April 12, forcing [[Battle of Fort Sumter|the fort's capitulation]]. Northerners rallied behind Lincoln's call for all of the states to send troops to recapture the forts and to preserve the Union. With the scale of the rebellion apparently small so far, Lincoln called for 74,000 volunteers for 90 days. For months before that, several Northern governors had secretly readied their state militias, built up stocks of weapons, and drawn up emergency plans; they began to move forces to Washington the next day. The Confederates at the state and national level had neglected to make preparations for war.<ref> See the account at [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN1582180016&id=ub8cqVKoXwgC&pg=PA35&lpg=PA34&vq=baltimore&dq=schouler+massachusetts+civil&sig=g5za9rXjH9ttx1vzmWNN39F3YFQ]</ref> | ||

Four states in the upper South | Four states in the upper South, Tennessee, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Virginia, which had repeatedly rejected Confederate overtures, now refused to send forces against their neighbors, declared their secession, and joined the Confederacy. To reward Virginia, the Confederate capital was moved to [[Richmond, Virginia|Richmond]]. The city became the symbol of the Confederacy; if it fell, the new nation would lose legitimacy. Richmond was in a highly vulnerable location at the end of a tortuous supply line. Although Richmond was heavily fortified, supplies for the city were be reduced by Sherman's capture of Atlanta and cut off almost entirely when Grant besieged [[Petersburg, Virginia|Petersburg]] and its railroads that supplied the Southern capital. | ||

===Anaconda Plan and blockade, 1861=== | ===Anaconda Plan and naval blockade, 1861-62=== | ||

[[Winfield Scott]], the commanding general of the U.S. Army, devised the [[Anaconda Plan]] | [[Winfield Scott]], the commanding general of the U.S. Army, devised the [[Anaconda Plan]] to win the war with as little bloodshed as possible. His idea was that a [[Union blockade]] of the main ports would weaken the Confederate economy; then the capture of the Mississippi River would split the South. Lincoln adopted the plan, but overruled Scott's warnings against an immediate attack on Richmond. Lincoln had to capture Richmond to destroy's the Confederacy's legitimacy as a nation. | ||

In May 1861, Lincoln proclaimed the [[Union blockade]] of all southern ports, which immediately shut down almost all international shipping to the Confederate ports. Violators risked seizure of the ship and cargo, and insurance probably would not cover the losses. Almost no large ships were owned by Confederate interests. By late 1861, the blockade shut down most local port-to-port traffic as well. Although few naval battles were fought and few men were killed, the blockade shut down | In May 1861, Lincoln proclaimed the [[Union blockade]] of all southern ports, which immediately shut down almost all international shipping to the Confederate ports. Violators risked seizure of the ship and cargo, and insurance probably would not cover the losses. Almost no large ships were owned by Confederate interests. By late 1861, the blockade shut down most local port-to-port traffic as well. Although few naval battles were fought and few men were killed, the blockade shut down "King Cotton" and ruined the southern economy. Some British investors built small, very fast "blockade runners" that brought in military supplies (and civilian luxuries) from Cuba and the Bahamas and took out high-priced cotton and tobacco. When the U.S. Navy did capture blockade runners, the ships and cargo were sold and the proceeds given to the Union sailors. The British crews were released. In March 1862 the Confederate navy sent its ironclad [[CSS Virginia|CSS ''Virginia'']] (the rebuilt USS ''Merrimac'') to attack the blockade; it seemed unstoppable but the next day it had to fight the new Union warship [[USS Monitor|USS ''Monitor'']] in the "Battle of the Ironclads". It was a strategic Union victory, for the blockade was sustained, and the Union built many copies of the ''Monitor'' while the Confederacy sank its own ship and lacked the technology to build more. The Confederacy turned to Britain to purchase warships, which the Union diplomats tried to stop. The Union won a series of naval battles in the rivers and harbors, taking control of the excellent waterway system to move its forces at will, while Confederates had to march overland. Union victory at the Fort Fisher in January 1865 closed the last useful rebel port and virtually ended blockade running. | ||

As the blockade became increasingly effective, the South had a shortage of almost everything, including food. When added to the effects of foraging by Northern armies and impressment of crops by Confederate armies, the result was hyper-inflation and even bread riots. | As the blockade became increasingly effective, the South had a shortage of almost everything, including food. When added to the effects of foraging by Northern armies and impressment of crops by Confederate armies, the result was hyper-inflation and even bread riots. | ||

===Eastern Theater 1861–1863=== | ===Eastern Theater 1861–1863=== | ||

The first major battle was a Confederate victory at [[First Battle of Bull Run]] , or ''First Manassas'' on July 1, 1861. It was here that Confederate General [[Stonewall Jackson]] received the nickname of "Stonewall" because he stood like a stone wall against Union troops. Alarmed at the loss, and in an attempt to prevent more border slave states from leaving the Union, the U.S. Congress passed the [[Crittenden-Johnson Resolution]] on July 25, 1861, which stated that the war was being fought to preserve the Union and not to end slavery. | |||

Major General [[George B. McClellan]] took command of the Union [[Army of the Potomac]] on July 26 (he was briefly general-in-chief of all the Union armies, but was subsequently relieved of that post in favor of Henry W. Halleck), and the war began in earnest in 1862. | |||

Upon the strong urging of President Lincoln to begin offensive operations, McClellan attacked Virginia in the spring of 1862 by way of the peninsula between the York River and James River, southeast of Richmond. Although McClellan's army reached the gates of Richmond in the [[Peninsula Campaign]], Confederate General [[Joseph E. Johnston]] halted his advance at the [[Battle of Seven Pines]], then General Robert E. Lee defeated him in the [[Seven Days Battles]] and forced his retreat. McClellan resisted Halleck's orders to send reinforcements to John Pope's Union [[Army of Virginia]], which made it easier for Lee's Confederates to defeat twice the number of combined enemy troops. Pope threw his troops piecemeal at the enemy, the Union's Irvin McDowell and Fitz John Porter did little, and Confederate [[James Longstreet|Longstreet's]] troops reinforced Stonewall Jackson's Confederates. The [[Northern Virginia Campaign]], which included the [[Second Battle of Bull Run]], ended in yet another victory for the South. | |||

====[[Battle of Antietam|Antietam]] to Chancellorsville==== | |||

Emboldened by Second Bull Run, the Confederacy made its first invasion of the North, when General Lee led 45,000 men of the [[Army of Northern Virginia]] across the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5. Lincoln then restored Pope's troops to McClellan. McClellan and Lee fought at the [[Battle of Antietam]] near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, the bloodiest single day in American military history. Lee's army, almost trapped, managed to escape and return to Virginia. Antietam was a strategic Union victory because it halted Lee's invasion of the North and provided an opportunity for Lincoln to announce his [[Emancipation Proclamation]]. | |||

When the cautious McClellan failed to follow up on Antietam, he was replaced by Maj. Gen. [[Ambrose Burnside]]. Burnside was soon defeated at the [[Battle of Fredericksburg]] on December 13, 1862, when over twelve thousand Union soldiers were killed or wounded. After the battle, Burnside was replaced by Maj. Gen. [[Joseph Hooker]]. Hooker, too, proved unable to defeat Lee's army; despite outnumbering the Confederates by more than two to one, he was humiliated in the [[Battle of Chancellorsville]] in May 1863. | |||

===Gettysburg=== | |||

see [[Gettysburg Campaign]] | |||

Hooker was replaced by Maj. Gen. [[George Meade]] during Lee's second invasion of the North, in June. Meade defeated Lee at the [[Gettysburg Campaign|Battle of Gettysburg]]<ref>McPherson, ''Battle Cry'', pages 653-663</ref> (July 1 to July 3, 1863), the bloodiest battle in United States history. Gettysburg is considered the turning point of the American Civil War by some historians; others argue the South was doomed after Antietam in 1862. Pickett's Charge on July 3 is often recalled as the high-water mark of the Confederacy, not just because its failure signaled the end of Lee's plan to pressure Washington from the north, but also because Vicksburg, Mississippi, the key stronghold to control of the Mississippi fell the following day. Lee's army suffered some 28,000 casualties (versus Meade's 23,000). However, Lincoln was angry that Meade failed to intercept Lee's retreat, and after Meade's inconclusive fall campaign, Lincoln decided to turn to the Western Theater for new leadership. | |||

===Western Theater 1861–1863=== | ===Western Theater 1861–1863=== | ||

While the Confederate forces had many successes in the Eastern theater, they were often defeated in the West. They were driven from Missouri early in the war as a result of the [[Battle of Pea Ridge]]. [[Leonidas Polk]]'s invasion of Columbus, Kentucky ended Kentucky's policy of neutrality and turned that state against the Confederacy. | |||

While the Confederate forces had | |||

[[Nashville, Tennessee]], fell to the Union early in 1862. Most of the [[Mississippi River|Mississippi]] was opened with the taking of [[Battle of Island Number Ten|Island No. 10]] and [[New Madrid, Missouri]], and then [[Memphis, Tennessee]]. The | [[Nashville, Tennessee]], fell to the Union early in 1862. Most of the [[Mississippi River|Mississippi]] was opened with the taking of [[Battle of Island Number Ten|Island No. 10]] and [[New Madrid, Missouri]], and then [[Memphis, Tennessee]]. The Union Navy captured [[New Orleans, Louisiana|New Orléans]] without a major fight in May 1862, allowing the Union forces to begin moving up the Mississippi as well. Only the fortress city of [[Vicksburg, Mississippi]], prevented unchallenged Union control of the entire river. | ||

General | General Braxton Bragg's second Confederate invasion of Kentucky ended with a meaningless victory over Major General [[Don Carlos Buell]] at the [[Battle of Perryville]], although Bragg was forced to end his attempt at liberating Kentucky and retreat due to lack of support for the Confederacy in that state. Bragg was narrowly defeated by Major General William Rosecrans at the [[Battle of Stones River]] in Tennessee. | ||

The one clear Confederate victory in the West was the [[Battle of Chickamauga]]. Bragg, reinforced by Lt. Gen. [[James Longstreet]]'s corps (from Lee's army in the east), defeated Rosecrans, despite the heroic defensive stand of | The one clear Confederate victory in the West was the [[Battle of Chickamauga]]. Bragg, reinforced by Lt. Gen. [[James Longstreet]]'s corps (from Lee's army in the east), defeated Rosecrans, despite the heroic defensive stand of Major General George Henry Thomas. Rosecrans retreated to [[Chattanooga, Tennessee|Chattanooga]], which Bragg then besieged. | ||

The Union's key strategist and tactician in the West was Maj. Gen. [[Ulysses S. Grant]], who won victories at Forts [[Battle of Fort Henry|Henry]] and [[Battle of Fort Donelson|Donelson]], by which the Union seized control of the [[Tennessee River|Tennessee]] and [[Cumberland River|Cumberland]] Rivers; [[Battle of Shiloh|the Battle of Shiloh]]; | The Union's key strategist and tactician in the West was Maj. Gen. [[Ulysses S. Grant]], who won victories at Forts [[Battle of Fort Henry|Henry]] and [[Battle of Fort Donelson|Donelson]], by which the Union seized control of the [[Tennessee River|Tennessee]] and [[Cumberland River|Cumberland]] Rivers; [[Battle of Shiloh|the Battle of Shiloh]]; the [[Battle of Vicksburg]], cementing Union control of the Mississippi River and considered one of the "turning points" of the war. Grant marched to the relief of Rosecrans and defeated Bragg at the [[Battle of Chattanooga III|Third Battle of Chattanooga]], driving Confederate forces out of Tennessee and opening a route to Atlanta and the heart of the Confederacy. | ||

===Trans-Mississippi Theater 1861–1865=== | ===Trans-Mississippi Theater 1861–1865=== | ||

Although geographically isolated from the battles to the east, a few small-scale military actions took place west of the Mississippi River. Confederate incursions into Arizona and New Mexico were repulsed in 1862. Guerrilla activity turned much of Missouri and Indian Territory (Oklahoma) into a battleground. Late in the war, the Union [[Red River Campaign]] was a failure. Texas remained in Confederate hands throughout the war, but was cut off from the rest of the Confederacy after the capture of Vicksburg in 1863 gave the Union control of the Mississippi River. | |||

===End of the war 1864–1865=== | ===End of the war 1864–1865=== | ||

{{Image|Lincoln and his advisors.jpg|right|350px|Abraham Lincoln meets with military advisors. Left to right: Gens. William T. Sherman, Ulysses S. Grant, Lincoln, and Adm. David S. Porter.}} | |||

At the beginning of 1864, Lincoln made Grant commander of all Union armies. Grant made his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, and put Major General [[William Tecumseh Sherman]] in command of most of the western armies. Grant understood the concept of "total war" and believed, along with Lincoln and Sherman, that only the utter defeat of Confederate forces and their economic base would end the war.<ref>Mark E. Neely Jr. (2004) Was the Civil War a Total War? ''Civil War History'', 50:434+</ref> | |||

Grant devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the entire Confederacy from multiple directions: Generals George Meade and [[Benjamin Franklin Butler (politician)|Benjamin Butler]] were ordered to move against Lee near Richmond; General [[Franz Sigel]] (and later [[Philip Sheridan]]) were to [[Valley Campaigns of 1864|attack the Shenandoah Valley]]; General Sherman was to capture Atlanta and march to the sea (the Atlantic Ocean); Generals George Crook and William W. Averell were to operate against railroad supply lines in [[West Virginia (U.S. state)|West Virginia]]; and Maj. Gen. [[Nathaniel Prentice Banks|Nathaniel P. Banks]] was to capture [[Mobile, Alabama]]. | |||

Union forces in the East attempted to maneuver past Lee and fought several battles during that phase ("Grant's [[Overland Campaign]]") of the Eastern campaign. Grant's battles of attrition at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor resulted in heavy Union losses, but forced Lee's Confederates to fall back again and again. An attempt to outflank Lee from the south failed under Butler, who was trapped inside the [[Bermuda Hundred Campaign|Bermuda Hundred]] river bend. Grant was tenacious and, despite astonishing losses (over 66,000 casualties in six weeks), kept pressing Lee's Army of Northern Virginia back to Richmond. He pinned down the Confederate army in the [[Siege of Petersburg]], where the two armies engaged in [[trench warfare]] for over nine months. | |||

Grant finally found a commander, General [[Philip Sheridan]], aggressive enough to prevail in the [[Valley Campaigns of 1864]]. Sheridan defeated Maj. Gen. [[Jubal Anderson Early|Jubal A. Early]] in a series of battles, including a final decisive defeat at [[Battle of Cedar Creek|the Battle of Cedar Creek]]. Sheridan then proceeded to destroy the agricultural base of the [[Shenandoah Valley]], a strategy similar to the tactics Sherman later employed in Georgia. | |||

Meanwhile, Sherman marched from Chattanooga to Atlanta, defeating Confederate Generals [[Joseph E. Johnston]] and [[John Bell Hood]] along the way. [[Battle of Atlanta|The fall of Atlanta]],<ref>McPherson, Battle Cry, pages 773-775</ref> on September 2 1864, was a significant factor in the reelection of Lincoln as president. Hood left the Atlanta area to menace Sherman's supply lines and invade Tennessee in the [[Franklin-Nashville Campaign]]. Union Maj. Gen. [[John M. Schofield]] defeated Hood at [[Battle of Franklin|the Battle of Franklin]], and [[George H. Thomas]] dealt Hood a massive defeat at [[Battle of Nashville|the Battle of Nashville]], effectively destroying Hood's army. | |||

Leaving Atlanta, and his base of supplies, Sherman's army marched with an unknown destination, laying waste to about 20% of the farms in Georgia in his "[[Sherman's March to the Sea|March to the Sea]]". He reached the Atlantic Ocean at [[Savannah, Georgia]] in December 1864. Sherman's army was followed by thousands of freed slaves; there were no major battles along the March. Sherman turned north through South Carolina and North Carolina to approach the Confederate Virginia lines from the south, increasing the pressure on Lee's army. | |||

Lee's army, thinned by desertion and casualties, was now much smaller than Grant's. Union forces won a decisive victory at the [[Battle of Five Forks]] on April 1, forcing Lee to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond. The Confederate capital fell to the Union XXV Corps, comprised of black troops. The remaining Confederate units fled west and after a defeat at Sayler's Creek, it became clear to Lee that continued fighting was hopeless. | |||

Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, at [[Appomattox Court House]]. As a mark of Grant's respect and anticipation of folding the Confederacy back into the Union with dignity and peace, Lee's men kept their horses and side arms. Johnston surrendered his troops to Sherman on April 2, 1865, in Durham, North Carolina. One after another the Confederate units surrendered; there was no guerrilla warfare, but many Confederate leaders were allowed to escape the country.<ref>On June 23 1865, at Fort Towson in the Choctaw Nations' area of the Oklahoma Territory, [[Stand Watie]] signed a cease-fire agreement with Union representatives, becoming the last Confederate general to stand down. The last Confederate naval force to surrender was the CSS ''Shenandoah'' on November 4, 1865, in Liverpool, England.</ref> | |||

Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia on | |||

==Slavery during the war== | ==Slavery during the war== | ||

{{main| | {{main|Slavery, U.S}} | ||

At the beginning of the war some Union commanders thought they were supposed to return escaped slaves to their masters. By 1862, when it became clear that this would be a long war, the question of what to do about slavery became more general. The Southern economy and military effort depended on slave labor. It began to seem unreasonable to protect slavery while blockading Southern commerce and destroying Southern production. As one Congressman put it, the slaves "…cannot be neutral. As laborers, if not as soldiers, they will be allies of the rebels, or of the Union."<ref>MacPherson, ''Battle Cry of Freedom'' page 495</ref> The same Congressman—and his fellow Radical Republicans—put pressure on Lincoln to rapidly emancipate the slaves, whereas Conservative Republicans came to accept gradual, compensated emancipation and colonization. | At the beginning of the war some Union commanders thought they were supposed to return escaped slaves to their masters. By 1862, when it became clear that this would be a long war, the question of what to do about slavery became more general. The Southern economy and military effort depended on slave labor. It began to seem unreasonable to protect slavery while blockading Southern commerce and destroying Southern production. As one Congressman put it, the slaves "…cannot be neutral. As laborers, if not as soldiers, they will be allies of the rebels, or of the Union."<ref>MacPherson, ''Battle Cry of Freedom'' page 495</ref> The same Congressman—and his fellow Radical Republicans—put pressure on Lincoln to rapidly emancipate the slaves, whereas Conservative Republicans came to accept gradual, compensated emancipation and colonization. | ||

In 1861 Lincoln expressed the fear that premature attempts at emancipation would mean the loss of the border states, and that "to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game."<ref>Lincoln's letter to O. H. Browning, Sep 22, 1861</ref> At first Lincoln reversed attempts at emancipation by Secretary of War | In 1861 Lincoln expressed the fear that premature attempts at emancipation would mean the loss of the border states, and that "to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game."<ref>Lincoln's letter to O. H. Browning, Sep 22, 1861</ref> At first Lincoln reversed attempts at emancipation by Secretary of War Simon Cameron and Generals [[John C. Fremont]] (in Missouri) and [[David Hunter]] (in the South Carolina Sea Islands) in order to keep the loyalty of the border states and the War Democrats. Lincoln then tried to persuade the border states to accept his plan of gradual, compensated emancipation and voluntary colonization, while warning them that stronger measures would be needed if the moderate approach was rejected. Only the District of Columbia accepted Lincoln's gradual plan, and Lincoln issued his final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1 of 1863. In his letter to Hodges, Lincoln explained his belief that "If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong … And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling ... I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me."<ref> Lincoln's Letter to A. G. Hodges, April 4, 1864</ref> | ||

The Emancipation Proclamation, | The Emancipation Proclamation, announced in September 1862 and put into effect four months later, greatly reduced the Confederacy's hope of getting aid from Britain or France. Lincoln's moderate approach succeeded in getting border states, War Democrats and emancipated slaves fighting on the same side for the Union. | ||

The Union-controlled border states (Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia) were not covered by the Emancipation Proclamation. All abolished slavery on their own, except Kentucky. The great majority of the 4 million slaves were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, as Union armies moved South. The | The Union-controlled border states (Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia) were not covered by the Emancipation Proclamation. All abolished slavery on their own, except Kentucky. The great majority of the 4 million slaves were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, as Union armies moved South. The 13th amendment, ratified December 6, 1865, finally freed the remaining 40,000 slaves in Kentucky.<ref> It also freed 1,000 or so slaves in Delaware and some lifetime servants in West Virginia and black slaves owned by Indians in Oklahoma.</ref> | ||

==Threat of international intervention== | ==Threat of international intervention== | ||

Entry into the war by Britain and France on behalf of the Confederacy would have greatly increased the South's chances of winning independence from the Union. The Union, under Lincoln and Secretary of State [[William Henry Seward]] worked to block this, and threatened war if any country officially recognized the existence of the Confederate States of America (none ever did). In 1861, Southerners voluntarily embargoed cotton shipments, hoping to start an economic depression in Europe that would force Britain to enter the war in order to get cotton. [[Cotton diplomacy]] proved a failure as Europe had a surplus of cotton, while the 1860-62 crop failures in Europe made the North's grain exports of critical importance. It was said that "King Corn was more powerful than King Cotton", as US grain went from a quarter of the British import trade to almost half. | Entry into the war by Britain and France on behalf of the Confederacy would have greatly increased the South's chances of winning independence from the Union. The Union, under Lincoln and Secretary of State [[William Henry Seward]] worked to block this, and threatened war if any country officially recognized the existence of the Confederate States of America (none ever did). In 1861, Southerners voluntarily embargoed cotton shipments, hoping to start an economic depression in Europe that would force Britain to enter the war in order to get cotton. [[Cotton diplomacy]] proved a failure as Europe had a surplus of cotton, while the 1860-62 crop failures in Europe made the North's grain exports of critical importance. It was said that "King Corn was more powerful than King Cotton", as US grain went from a quarter of the British import trade to almost half. | ||

When | When Britain did face a cotton shortage in 1862, it was temporary; being replaced by sales from the U.S. (which purchased cotton from compliant planters), and from increased production in Egypt and India. The war created employment for arms makers, iron workers, and shipbuilders.<ref>Allen Nevins, ''War for the Union 1862-1863'', pages 263-264</ref> | ||

[[Charles Francis Adams | [[Charles Francis Adams Sr.|Charles Francis Adams]] proved particularly adept as minister to Britain for the Union, and Britain was reluctant to boldly challenge the Union's blockade. Independent British maritime interests built and operated highly profitable blockade runners — commercial ships flying the British flag and carrying supplies to the Confederacy by slipping through the blockade. The officers and crews were British and when captured they were released. The Confederacy purchased several warships from commercial ship builders in Britain; the most famous, the CSS ''Alabama'', did considerable damage and led to serious postwar disputes. However, public opinion against slavery created a political liability for European politicians, especially in Britain. War loomed in late 1861 between the U.S. and Britain over the [[Trent Affair]], when the U.S., Navy violated international law by boarding a British mail steamer to seize two Confederate diplomats, James Mason and John Slidell. However, London and Washington were able to smooth over the crisis after Lincoln released the two. | ||

In 1862, the British considered | In 1862, the British considered mediation—-though even such an offer would have risked war with the U.S. The Union victory in the [[Battle of Antietam]] caused [[Lord Palmerston]] to delay this decision. The [[Emancipation Proclamation]] made direct support of the Confederacy and slavery politically impossible in Britain. Despite some sympathy for the Confederacy, France's own seizure of Mexico ultimately deterred them from war with the Union. Confederate offers late in the war to end slavery in return for diplomatic recognition were not seriously considered by London or Paris. | ||

==Destruction== | |||

===War dead=== | |||

The war produced about 970,000 military casualties (3% of the population), including approximately 620,000 soldier deaths—two-thirds by disease. The 10,500 battles and engagements produced about 1,1 million killed and wounded. The Union army and navy lost 110,100 killed in action (including mortally wounded who died in hospitals), and another 224,580 who died of disease. The Confederate army 94,000 in battle and another 164,000 who died of disease. Official counts of the wounded are far too low, at 275,000 for the Union and 194,000 for the Confederacy.<ref> For details see Thomas L. Livermore, ''Numbers and Losses in the Civil War in America 1861-65'' (1901) [http://books.google.com/books?id=jthCAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=intitle:Numbers+intitle:and+intitle:Losses+intitle:in+intitle:the+intitle:Civil+intitle:War&lr=&num=30&as_brr=0 full text online]; and William F. Fox, ''Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1867-1865'' (1889). see also [http://www.civilwarhome.com/links13.htm#casualties websites dealing with the casualty count]</ref> | |||

===Civilian destruction=== | |||

The number of civilian deaths is unknown. Most of the war was fought in Virginia and Tennessee, but every Southern state was affected as well as Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky Missouri, and Indian Territory; Pennsylvania was the only northerner state to be the scene of major action, during the Gettysburg campaign. In the Confederacy there was little military action in Texas and Florida. Of 645 counties in 9 Confederate states (excluding Texas and Florida), there was Union military action in 56% of them, containing 63% of the whites and 64% of the slaves in 1860; however by the time the action took place some people had fled to safer areas, so the exact population exposed to war is unknown. | |||

The Confederacy in 1861 had 297 towns and cities with 835,000 people; of these 162 with 681,000 people were at one point occupied by Union forces. Eleven were destroyed or severely damaged by war action, including Atlanta (with an 1860 population of 9,600), Charleston, Columbia, and Richmond (with prewar populations of 40,500, 8,100, and 37,900, respectively); the eleven contained 115,900 people in the 1860 census, or 14% of the urban South. Historians have not estimated their population when they were invaded. The number of people who lived in the destroyed towns represented just over 1% of the Confederacy's population. In addition, 45 court houses were burned (out of 830). The South's agriculture was not highly mechanized. The value of farm implements and machinery in the 1860 Census was $81 million; by 1870, there was 40% less, of $48 million worth. Many old tools had broken through heavy use and could not be replaced; even repairs were difficult. | |||

The economic calamity suffered by the South during the war affected every family. Except for land, most assets and investments had vanished with slavery, but debts were left behind. Worst of all were the human deaths and amputations. Most farms were intact but most had lost their horses, mules and cattle; fences and barns were in disrepair. Prices for cotton had plunged. The rebuilding would take years and require outside investment because the devastation was so thorough. One historian has summarized the collapse of the transportation infrastructure needed for economic recovery:<ref> John Samuel Ezell, ''The South since 1865'' 1963 pp 27-28</ref> | |||

:One of the greatest calamities which confronted Southerners was the havoc wrought on the transportation system. Roads were impassable or nonexistent, and bridges were destroyed or washed away. The important river traffic was at a standstill: levees were broken, channels were blocked, the few steamboats which had not been captured or destroyed were in a state of disrepair, wharves had decayed or were missing, and trained personnel were dead or dispersed. Horses, mules, oxen, carriages, wagons, and carts had nearly all fallen prey at one time or another to the contending armies. The railroads were paralyzed, with most of the companies bankrupt. These lines had been the special target of the enemy. On one stretch of 114 miles in Alabama, every bridge and trestle was destroyed, cross-ties rotten, buildings burned, water-tanks gone, ditches filled up, and tracks grown up in weeds and bushes. . . . Communication centers like Columbia and Atlanta were in ruins; shops and foundries were wrecked or in disrepair. Even those areas bypassed by battle had been pirated for equipment needed on the battlefront, and the wear and tear of wartime usage without adequate repairs or replacements reduced all to a state of disintegration. | |||

Railroad mileage was of course located mostly in rural areas. The war followed the rails, and over two-thirds of the South's rails, bridges, rail yards, repair shops and rolling stock were in areas reached by Union armies, which systematically destroyed what it could. The South had 9400 miles of track and 6500 miles was in areas reached by the Union armies. About 4400 miles were in areas where Sherman and other Union generals adopted a policy of systematic destruction of the rail system. Even in untouched areas, the lack of maintenance and repair, the absence of new equipment, the heavy over-use, and the deliberate movement of equipment by the Confederates from remote areas to the war zone guaranteed the system would be virtually ruined at war's end.<ref> Paul F. Paskoff, "Measures of War: A Quantitative Examination of the Civil War's Destructiveness in the Confederacy," ''Civil War History'' 54.1 (2008) 35-62</ref> | |||

==Analysis of the outcome== | ==Analysis of the outcome== | ||

Since the war's end, | Since the war's end, historians have tried to devise scenarios whereby the South could have won independence. In every scenario that requires military intervention by Britain. Absent that intervention, experts argue that the Union held an insurmountable advantage in terms of industrial strength, population, and the determination to win. Confederate victories on the battlefield, they argue, could only delay defeat. Southern historian [[Shelby Foote]] expressed this view succinctly: "I think that the North fought that war with one hand behind its back.… If there had been more Southern victories, and a lot more, the North simply would have brought that other hand out from behind its back. I don't think the South ever had a chance to win that War."<ref>Ward 1990 p 272</ref> The Confederacy strategy was to rely on war-weariness in the North and victory by Copperheads. However, after Atlanta fell and Lincoln defeated McClellan by a massive landslide in the election of 1864, those slim hopes evaporated. At that point, Lincoln had succeeded in getting the support of the border states and War Democrats, and kept Britain and France neutral. By defeating the Democrats and McClellan, he also defeated the [[Copperheads]] and their peace platform. Lincoln now had found military leaders like Grant and Sherman who would press the Union's numerical advantage in battle over the Confederate Armies. Generals who didn't shy from bloodshed won the war, and from the end of 1864 onward there was no hope for the South. Lincoln offered peace terms to top Confederate officials in February 1865, involving reunion and purchase of the slaves for cash. The Confederates insisted on independence and fought to the bitter end. | ||

The goals were not symmetric. To win independence, the South had to convince the North it could not win, but the South ''did not'' have to invade the North. To restore the Union, the North had to conquer and occupy vast stretches of territory. In the short run (a matter of months), the two sides were evenly matched. But in the long run (a matter of years), the North had advantages that increasingly came into play, while it prevented the South from gaining diplomatic recognition in Europe. | The goals were not symmetric. To win independence, the South had to convince the North it could not win, but the South ''did not'' have to invade the North. To restore the Union, the North had to conquer and occupy vast stretches of territory. In the short run (a matter of months), the two sides were evenly matched. But in the long run (a matter of years), the North had advantages that increasingly came into play, while it prevented the South from gaining diplomatic recognition in Europe. | ||

Also important were Lincoln's eloquence in rationalizing the national purpose and his skill in keeping the border states committed to the Union cause. Although Lincoln's approach to emancipation was slow, the Emancipation Proclamation was an effective use of the President's war powers.<ref>[http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jala/9/fehrenbacher.html Lincoln' | Also important were Lincoln's eloquence in rationalizing the national purpose and his skill in keeping the border states committed to the Union cause. Although Lincoln's approach to emancipation was slow, the Emancipation Proclamation was an effective use of the President's war powers.<ref>Don E. Fehrenbacher, "Lincoln's Wartime Leadership: The First Hundred Days." [http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jala/9/fehrenbacher.html ''Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association'' 9.1 (1987): online]</ref> | ||

===Long-term economic factors=== | ===Long-term economic factors=== | ||

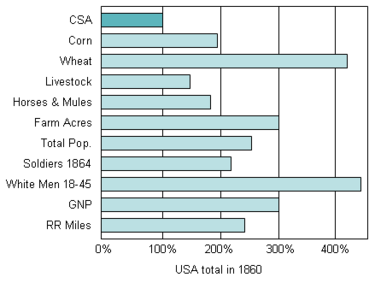

{{Image|USA Advantages.png|right|375px|USA economic advantages; graph shows USA value with CSA = 100; the longer the bar, the greater the North's advantage. Data shown is at start of the war, but USA advantages increased every month. Source: ''Census of 1860''}} | |||

The more industrialized economy of the North aided in the production of arms, munitions and supplies, as well as finances, and transportation. These advantages widened rapidly during the war, as the Northern economy grew, and Confederate territory shrank and its economy weakened. The Union population was 22 million and the South 9 million in 1861; the Southern population included more than 3.5 million slaves and about 5.5 million whites, thus leaving the South's white population outnumbered by more than four to one. The disparity grew as the Union controlled more and more southern territory with garrisons, and cut off the trans-Mississippi part of the Confederacy. The Union at the start controlled over 80% of the shipyards, steamships, river boats, and the Navy. It augmented these by a massive shipbuilding program. This enabled the Union to control the river systems and to blockade the entire southern coastline. Excellent railroad links between Union cities allowed for the quick and cheap movement of troops and supplies. Transportation was much slower and more difficult in the South which was unable to augment its much smaller rail system, repair damage, or even perform routine maintenance. | |||

====Logistics and supply==== | |||