Frontier Thesis: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen (changes) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}}{{TOC|right}} | |||

Turner | The '''Frontier Thesis''' or '''Turner Thesis''' is the conclusion of [[Frederick Jackson Turner]] that the wellsprings of American character and vitality have always been the [[American frontier]], the region between civilized society and the untamed wilderness. In the thesis, the frontier created freedom, "breaking the bonds of custom, offering new experiences, [and] calling out new institutions and activities." | ||

==Origins== | |||

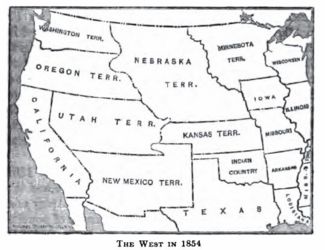

[[Image:West1854.jpg|thumb|325px]] | |||

Writers such as [[Ralph Waldo Emerson]] had speculated on the importance of the west, and [[Theodore Roosevelt]] wrote a full-scale history of the Tennessee frontier that argued the experience formed a new "race"—the American people. Turner drew on his knowledge of evolution, and his own research into the [[fur trade]] frontier. He first announced his thesis in a paper entitled "The Significance of the Frontier in American History," delivered to the [[American Historical Association]] in 1893 at the [[World Columbian Exposition]] in Chicago. This thesis dominated much of the scholarship on the history of the United States until the 1960s. It was then challenged by the "New Western Historians," who ignored its valid conclusions but instead charged that it ignored ethnic minorities and women and was too praiseworthy of the pioneers. | |||

==Evolutionary model== | |||

Turner set up an evolutionary model (he had studied evolution with a leading geologist), using the time dimension of American history, and the geographical space of the land that became the United States. His argument was that the new environment had caused a rapid evolution of social and political characteristics, thereby creating the true "American." The first settlers who arrived on the east coast in the 17th century acted and thought like Europeans. They encountered a new environmental challenge that was quite different from what they had known. The most important difference was vast amounts of unused high quality farmland (some of which was used by a few thousand Indians for hunting grounds.) They adapted to the new environment in certain ways—the sum of all the adaptations over the years would make them Americans. The next generation moved further inland. It discarded more European aspects that were no longer useful, for example established churches, established aristocracies, intrusive government, and control of the best land by a small gentry class. Every generation moved further west and became more American, and the settlers became more democratic and less tolerant of hierarchy. They became more violent, more individualistic, more distrustful of authority, less artistic, less scientific, and more dependent on ad-hoc organizations they formed themselves. In broad terms, the further west, the more American the community. | |||

[[Merle Curti]], one of Turner's last students in 1944 won the [[Pulitzer Prize]] in history for ''The Growth of American Thought.'' Curti adapted Turner's frontier thesis to intellectual history, arguing, "Because the American environment, physical and social, differed from that of Europe, Americans, confronted by different needs and problems, adapted the European intellectual heritage in their own way. And because American life came increasingly to differ from European life, American ideas, American agencies of intellectual life, and the use made of knowledge likewise came to differ in America from their European counterparts." (p vi) His book was not so much a history of American thought as a social history of American thought, with strong attention to the social and economic forces that shaped that thought. | |||

- | ==Impact of thesis== | ||

< | Turner's thesis quickly became popular among intellectuals, as well as spokesmen for the west. It explained why the American people and American government were so different from Europeans. It sounded an alarming note about the future, since the U.S. Census of 1890 had officially stated that the American frontier line (separating the more-settled and lightly settled zones) had broken up. The idea that the source of America's power and uniqueness was gone was a distressing concept for some intellectuals. Some talked about overseas expansion as a new frontier; others (like [[John F. Kennedy]]) called for a "new frontier" of achievement. Despite criticism, Turner's theory entered its second century "in remarkably good shape."<ref> Limerick (1995) p 697</ref> | ||

== Provenance == | |||

{{WPAttribution}} | |||

[[Category: | |||

==Notes== | |||

<references/>[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:01, 19 August 2024

The Frontier Thesis or Turner Thesis is the conclusion of Frederick Jackson Turner that the wellsprings of American character and vitality have always been the American frontier, the region between civilized society and the untamed wilderness. In the thesis, the frontier created freedom, "breaking the bonds of custom, offering new experiences, [and] calling out new institutions and activities."

Origins

Writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson had speculated on the importance of the west, and Theodore Roosevelt wrote a full-scale history of the Tennessee frontier that argued the experience formed a new "race"—the American people. Turner drew on his knowledge of evolution, and his own research into the fur trade frontier. He first announced his thesis in a paper entitled "The Significance of the Frontier in American History," delivered to the American Historical Association in 1893 at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. This thesis dominated much of the scholarship on the history of the United States until the 1960s. It was then challenged by the "New Western Historians," who ignored its valid conclusions but instead charged that it ignored ethnic minorities and women and was too praiseworthy of the pioneers.

Evolutionary model

Turner set up an evolutionary model (he had studied evolution with a leading geologist), using the time dimension of American history, and the geographical space of the land that became the United States. His argument was that the new environment had caused a rapid evolution of social and political characteristics, thereby creating the true "American." The first settlers who arrived on the east coast in the 17th century acted and thought like Europeans. They encountered a new environmental challenge that was quite different from what they had known. The most important difference was vast amounts of unused high quality farmland (some of which was used by a few thousand Indians for hunting grounds.) They adapted to the new environment in certain ways—the sum of all the adaptations over the years would make them Americans. The next generation moved further inland. It discarded more European aspects that were no longer useful, for example established churches, established aristocracies, intrusive government, and control of the best land by a small gentry class. Every generation moved further west and became more American, and the settlers became more democratic and less tolerant of hierarchy. They became more violent, more individualistic, more distrustful of authority, less artistic, less scientific, and more dependent on ad-hoc organizations they formed themselves. In broad terms, the further west, the more American the community.

Merle Curti, one of Turner's last students in 1944 won the Pulitzer Prize in history for The Growth of American Thought. Curti adapted Turner's frontier thesis to intellectual history, arguing, "Because the American environment, physical and social, differed from that of Europe, Americans, confronted by different needs and problems, adapted the European intellectual heritage in their own way. And because American life came increasingly to differ from European life, American ideas, American agencies of intellectual life, and the use made of knowledge likewise came to differ in America from their European counterparts." (p vi) His book was not so much a history of American thought as a social history of American thought, with strong attention to the social and economic forces that shaped that thought.

Impact of thesis

Turner's thesis quickly became popular among intellectuals, as well as spokesmen for the west. It explained why the American people and American government were so different from Europeans. It sounded an alarming note about the future, since the U.S. Census of 1890 had officially stated that the American frontier line (separating the more-settled and lightly settled zones) had broken up. The idea that the source of America's power and uniqueness was gone was a distressing concept for some intellectuals. Some talked about overseas expansion as a new frontier; others (like John F. Kennedy) called for a "new frontier" of achievement. Despite criticism, Turner's theory entered its second century "in remarkably good shape."[1]

Provenance

- Some content on this page may previously have appeared on Wikipedia.

Notes

- ↑ Limerick (1995) p 697