Latino history: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen (add ww2) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Latino history''' is the history of Mexicans and other Hispanics in the United States from 1846 to the present. | {{subpages}} | ||

'''Latino history''' is the history of Mexicans and other [[Hispanics]] in the United States from 1846 to the present. By 2005 the Latino population reached 41.3 million,of whom 64% were Mexican, 10% Puerto Rican, 3% Cuban, 3% Dominican, 3% Salvadoran, and the remaining 17% from smaller groups.<ref> See Census Bureau press release, July 16, 2007 at [http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/010327.html]</ref> About 12 million undocumented ("illegal") immigrants live in the U.S., a number that has grown since the [[9/11 Attack|9/11]] attack of 2001. | |||

==19th century== | ==19th century== | ||

When Mexico took over control from Spain in the early 1820s, the new government ignored and isolated the "norteños" (inhabitants of Mexico's northern provinces), except to break up the mission system in [[California]]. The systematic [[Navajo]] and [[Apache]] raids on [[New Mexico]] villages and ranches were ignored, as was the vulnerability of California, as the central government pulled back its soldiers to use them in recurrent civil wars and factional battles. When [[Republic of Texas|Texas]] seemed too independent, [[Santa Anna]] led an army to massacre the villagers and destroy the American settlements. After initial victories and massacres at The Alamo and Goliad, Santa Anna was decisively defeated by the Texans, who declared independence. The Tejanos in Texas joined the revolution and supported the new Republic of Texas; The Hispanics in New Mexico and California were localistic and did not identify with the regime in Mexico City. The "norteños" played a minor role in the [[Mexican American War]] of 1846-48, and when offered the choice of repatriating to Mexico or remaining and becoming full citizens of the United States, the great majority remained. Only when large numbers of Americans arrived did they develop a sense of "lo mexicano," that is of "being Mexican," and that new identification had little to do with far-off Mexico. <ref> David G. Gutiérrez, "Migration, Emergent Ethnicity, and the "Third Space": The Shifting Politics of Nationalism in Greater Mexico" ''Journal of American History'' 1999 86(2): 481-517. ISSN: 0021-8723 [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8723(199909)86%3A2%3C481%3AMEEAT%22%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V in JSTOR]</ref> American entrepreneurs often cultivated alliances and partnerships with the Mexican propertied elites in the states of Texas and California, and the territories of New Mexico and Arizona. The Californios--who only numbered 10,000 in 1848, remained in California but were soon overwhelmed by the immigration of hundreds of thousands of newcomers to California, and largely became invisible to Anglos. The Latino culture of the rest of the Southwest, especially New Mexico and southern Texas, called itself "Spanish" (rather than "Mexican") to distinguish themselves from "los norteamericanos". The Latinos emphasized their own religion, language, customs and kinship ties, and drew into enclaves, rural | When Mexico took over control from Spain in the early 1820s, the new government ignored and isolated the "norteños" (inhabitants of Mexico's northern provinces), except to break up the mission system in [[California (U.S. state)]]. The systematic [[Navajo]] and [[Apache]] raids on [[New Mexico (U.S. state)|New Mexico]] villages and ranches were ignored, as was the vulnerability of California, as the central government pulled back its soldiers to use them in recurrent civil wars and factional battles. When [[Republic of Texas|Texas]] seemed too independent, Mexico's President [[Santa Anna]] led an army to massacre the villagers and destroy the American settlements. After initial victories and massacres at The Alamo and Goliad, Santa Anna was decisively defeated by the Texans, who declared independence. The Tejanos in Texas joined the revolution and supported the new Republic of Texas; The Hispanics in New Mexico and California were localistic and did not identify with the regime in Mexico City. The "norteños" played a minor role in the [[Mexican American War]] of 1846-48, and when offered the choice of repatriating to Mexico or remaining and becoming full citizens of the United States, the great majority remained. Only when large numbers of Americans arrived did they develop a sense of "lo mexicano," that is of "being Mexican," and that new identification had little to do with far-off Mexico. <ref> David G. Gutiérrez, "Migration, Emergent Ethnicity, and the "Third Space": The Shifting Politics of Nationalism in Greater Mexico" ''Journal of American History'' 1999 86(2): 481-517. ISSN: 0021-8723 [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8723(199909)86%3A2%3C481%3AMEEAT%22%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V in JSTOR]</ref> American entrepreneurs often cultivated alliances and partnerships with the Mexican propertied elites in the states of Texas and California, and the territories of New Mexico and Arizona. The Californios--who only numbered 10,000 in 1848, remained in California but were soon overwhelmed by the immigration of hundreds of thousands of newcomers to California, and largely became invisible to Anglos. The Latino culture of the rest of the Southwest, especially New Mexico and southern Texas, called itself "Spanish" (rather than "Mexican") to distinguish themselves from "los norteamericanos". The Latinos emphasized their own religion, language, customs and kinship ties, and drew into enclaves, rural colonies and urban barrios, which norteamericanos seldom entered; intermarriage rates were low. | ||

==20th century== | |||

{{Image|Texas-1905-Mexicans.jpg|right|250px|Mexican American field workers picking carrots in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, about 1905}} | |||

After 1911 the ferocious civil wars in Mexico led 600,000 to 1 million refugees to flee north across the border, which was generally open. Well educated middle class families as well as poor peons. | After 1911 the ferocious civil wars in Mexico led 600,000 to 1 million refugees to flee north across the border, which was generally open. Well educated middle class families emigrated, as well as poor peons. | ||

In | In Texas a band of radicals issued the manifesto "[[Plan de San Diego]]" in 1915 in South Texas calling on Hispanics to reconquer the Southwest and kill all the Anglo men. Rebels assassinated opponents and killed several dozen people in attacks on railroads and ranches before the Texas Rangers smashed the insurrection. Tejanos strongly repudiated the Plan and affirmed their American loyalty by founding the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). LULAC, headed by professionals, businessmen and modernizers, became the central Tejano organization promoting civic pride and civil rights.<ref> Benjamin H. Johnson, ''Revolution in Texas: how a forgotten rebellion and its bloody suppression turned Mexicans into Americans''. (2003). </ref> | ||

From 1945 to the early 1970s, large numbers of Latinos moved out of dead-end, low-wage work into higher-paying and higher-status skilled blue-collar occupations.<ref> 43% of the men were still unskilled workers or farm laborers in 1950; by 1960, the proportion had fallen to 33%.</ref> They and their children experienced steady gains in virtually all major socioeconomic indicators, including income, occupational status, English-language proficiency, years of education, and geographic mobility. The opportunities were in the cities; there was little upward mobility for those who remained in the California farmland or in the chronically depressed lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas, and in the isolated rural hamlets of Colorado and New Mexico.<ref> Bean and Tienda, ''The Hispanic Population of the United States'' (1987), 17-22, 280-337. </ref> | Over 500,000 returned after 1930, but many stayed. The consulates of the Mexican government in major cities in the Southwest organized a network of "juntas patrioticas" (patriotic councils) and "comisiónes honoríficos" (honorary committees) to celebrate Mexican national holidays such as the [[Cinco de Mayo]]; the target audience was the Latino middle class.<ref> In Mexico itself, the emergence of a national identity for the average person was the work of the 20th century. After 1920 the national government promoted "true" mexicanismo by stirring up anti-American sentiment; promoting contemporary Mexican art, music, and literature; extolling and placing new emphasis on the value of the nation's indigenous peoples and the heritage of mestizaje. Gutiérrez (1999)</ref> | ||

In borderlands towns such as Brownsville, Corpus Christi, Laredo, San Antonio, El Paso, Tucson, Yuma, San Diego, and Los Angeles, local Latino leaders wanted to restrict the influx of immigrants, because the newcomers directly competed with resident Latinos for jobs and housing and because they reinforced negative stereotypes regarding a lazy and violent lifestyle. In 1929 the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was formed on the premise that full acceptance of American social, educational and political values was the only way Latinos could reasonably expect to improve their political, economic, and social position in American society. Some upwardly mobile families joined [[Protestant]] churches, but most remained devout, conservative [[Roman Catholicism|Roman Catholics]]. From the early 1930s through the 1960s, LULAC's political agenda focused on citizenship training and naturalization of "foreign-born Mexicans," English-language training, active support of antidiscriminatory litigation and legislation (particularly regarding public schools), and strict control of further immigration from Mexico. LULAC promoted the liberal rhetoric of "equality" and "rights" and the mutual obligations of [[Republicanism, U.S.|republican civic duty]]. However, voting levels were quite low, and especially in South Texas the Latino vote was controlled by local "bosses." There was little in the way of radical movements. | |||

==World War II== | |||

World War II was a watershed for all the Latino groups. Some 500,000 were drafted; even larger numbers of the women and older men worked in high paying munitions plants, ending the hardship years of the [[Great Depression|depression]] and inspiring demands for upward mobility and political rights. The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and El Congreso de Pueblos de Hablan Española (the Spanish-Speaking Peoples' Congress), founded before the war, expanded their membership and more successfully demanded full integration for their middle class constituents. Labor unions opened their membership rolls and Luisa Moreno became the first Latina to hold a national union office, as vice-president of the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), and affiliate of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). | |||

===Post 1945=== | |||

From 1945 to the early 1970s, large numbers of Latinos moved out of dead-end, low-wage work into higher-paying and higher-status skilled blue-collar occupations.<ref> 43% of the men were still unskilled workers or farm laborers in 1950; by 1960, the proportion had fallen to 33%.</ref> They and their children experienced steady gains in virtually all major socioeconomic indicators, including income, occupational status, English-language proficiency, years of education, and geographic mobility. The opportunities were in the cities; there was little upward mobility for those who remained in the California farmland or in the chronically depressed lower [[Rio Grande]] Valley of Texas, and in the isolated rural hamlets of [[Colorado (U.S. state)|Colorado]] and [[New Mexico (U.S. state)|New Mexico]].<ref> Bean and Tienda, ''The Hispanic Population of the United States'' (1987), 17-22, 280-337. </ref> | |||

===Seasonal migration=== | |||

A common pattern emerged after 1940 of men working summers in the U.S. and spending the winter season in the village back in Mexico. While this became illegal in 1965, the numbers involved kept growing. By 2007 there were 12 million or so undocumented workers in the U.S.; they had jobs, often using fake identity cards. They made money in the U.S. but returned to the villages to spend it, attend [[fiesta]]s, tend to family business, and participate in extended kinship rituals such as [[baptism]]s, weddings, and funerals. After the increased border security following the [[9/11 Attack|9/11]] attack in 2001, the [[seasonal migration|back-and-forth pattern]] became dangerous. People kept coming north, but they stayed in the U.S. and sent money home every month. Locked into the American economy year-round, millions of these undocumented workers moved out of season agricultural jobs into year-round jobs in restaurants, hotels, construction, landscaping and semiskilled factory work, such as meat packing. Most paid federal social security taxes into imaginary accounts (and thus were not eligible for benefits.) Few had high enough incomes to pay federal or state income taxes, but all paid local and state sales taxes on their purchases as well as local property taxes (via their rent payments to landlords). | |||

==Politics== | ==Politics== | ||

Latinos engaged in national politics for the first time in 1960 when hundreds of "[[Viva Kennedy]]" clubs were created. As a result of military service in World War II the slowly improving civil rights atmosphere of the 1950s, Mexican Americans had tasted some limited successes in access to employment, education (particularly through the benefits of the G.I. Bill), and the election of a few government officials at the state and local levels. Moreover, with the establishment of new, aggressive Mexican American advocacy organizations in the Southwest between 1947 and 1959, community activists symbolically announced that Mexican Americans would henceforth be a political force with which to reckon. About 85% of the Mexican American vote went to Kennedy, slightly higher than other Catholic ethnics. The Latinos took credit for carrying California and Texas by razor-thin margins. President Kennedy, however, made some symbolic appointments but showed minimal interest in Mexican American issues. | Latinos engaged in national politics for the first time in 1960 when hundreds of "[[Viva Kennedy]]" clubs were created. As a result of military service in World War II the slowly improving civil rights atmosphere of the 1950s, Mexican Americans had tasted some limited successes in access to employment, education (particularly through the benefits of the G.I. Bill), and the election of a few government officials at the state and local levels. Moreover, with the establishment of new, aggressive Mexican American advocacy organizations in the Southwest between 1947 and 1959, community activists symbolically announced that Mexican Americans would henceforth be a political force with which to reckon. About 85% of the Mexican American vote went to Kennedy, slightly higher than other Catholic ethnics. The Latinos took credit for carrying California and Texas by razor-thin margins. President Kennedy, however, made some symbolic appointments but showed minimal interest in Mexican American issues. | ||

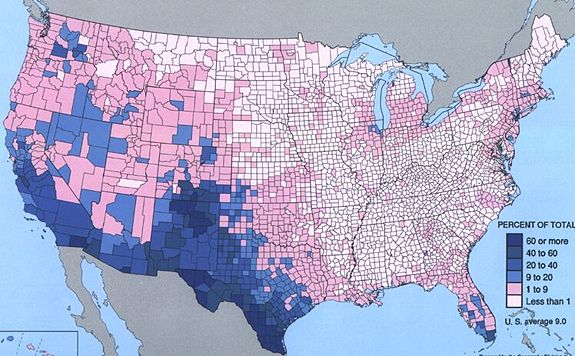

[[Image:Hispanic-US-1990.jpg|thumb|575px|Hispanic population 1990]] | |||

In 2000 and 2004 presidential elections, [[George W. Bush]] made a systematic effort to reach Latino voters, obtaining 40% of their vote. Most remained Democrats and in the 2008 presidential election, heavily favored [[Hillary Clinton]] over [[Barack Obama]] for the nomination. | |||

==Demography== | ==Demography== | ||

California in 2006 had the largest Hispanic population of any state as of 2006 (13.1 million), followed by Texas (8.4 million) and Florida (3.6 million). Texas had the largest numerical increase between 2005 and 2006 (305,000), with California (283,000) and Florida (161,000) following. In New Mexico, Hispanics comprised the highest proportion of the total population (44%), with California and Texas (36% each) next in line. The Hispanic population in 2006 was much younger, with a median age of 27.4 compared with the population as a whole at 36.4. About a third of the Hispanic population was younger than 18, compared with one-fourth of the total population.<ref> See Census report May 17, 2007 at [http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/population/010048.html] with details at [http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/cb07-70tbl2.xls]</ref> | California in 2006 had the largest Hispanic population of any state as of 2006 (13.1 million), followed by Texas (8.4 million) and Florida (3.6 million). Texas had the largest numerical increase between 2005 and 2006 (305,000), with California (283,000) and Florida (161,000) following. In New Mexico, Hispanics comprised the highest proportion of the total population (44%), with California and Texas (36% each) next in line. The Hispanic population in 2006 was much younger, with a median age of 27.4 compared with the population as a whole at 36.4. About a third of the Hispanic population was younger than 18, compared with one-fourth of the total population.<ref> See Census report May 17, 2007 at [http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/population/010048.html] with details at [http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/cb07-70tbl2.xls]</ref> | ||

The rapid growth of the Hispanic population after 1972 began in the Southwest, but spread nationwide by 2000. The diffusion of Latinos across the country was dramatic by 2008, and became a major issue in the presidential election, with Republicans echoing nativist hostilities. In Georgia, for example, there were barely 60,000 Latinos in 1980, and 100,000 in 1990, less than 2%. By the 2000 Census the number had surged to 435,000, or 5%, with continuing rapid growth to 700,000 in 2006.<ref> Bullock and Hood (2006)</ref> | |||

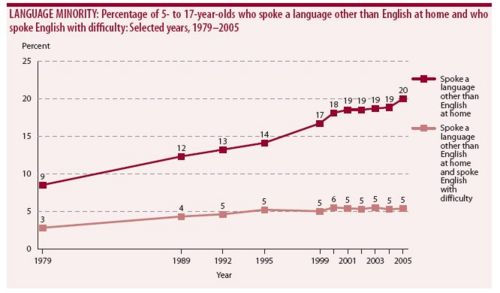

In 1972 Hispanics comprised 6% of public school students, and more than tripled to 20% in 2005. However, despite fears that assimilation would be difficult, the proportion of students who spoke English with difficulty has been flat at 5%, according to graph 1. | |||

[[Image:Language.jpg|thumb|500px|Graph 1: Trends in students from foreign language homes and proportion speaking English with difficulty]] | |||

==Puerto Ricans== | ==Puerto Ricans== | ||

The U.S. acquired Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898, and engaged in a massive modernization program involving disease control, sanitation, transportation, internal improvements, and medical care, along with corporate investment in sugar plantations. The island was overpopulated, so a systematic effort was made to assist migration. Over 5000 migrated to Hawaii (also acquired in 1898) to work in sugar plantations. By 1920 Puerto Ricans had full U.S. citizenship and had a presence in 45 states. New York City was the destination of 60%; children born anywhere on the mainland were dubbed "Nuyorican."<ref> Ruiz (2006)</ref> | The U.S. acquired Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898, and engaged in a massive modernization program involving disease control, sanitation, transportation, internal improvements, and medical care, along with corporate investment in sugar plantations. The island was overpopulated, so a systematic effort was made to assist migration. Over 5000 migrated to Hawaii (also acquired in 1898) to work in sugar plantations. By 1920 Puerto Ricans had full U.S. citizenship and had a presence in 45 states. New York City was the destination of 60%; children born anywhere on the mainland were dubbed "Nuyorican."<ref> Ruiz (2006)</ref> | ||

==Historiography== | ==Historiography== | ||

The study of Latino history raises a issues regarding the definition and boundaries of "Latino." Are Latinos a "group" and if so, what are its defining boundaries and characteristics? Is speaking Spanish a requirement to be Latino? Are indigenous peoples from Latin America part of the group? Do Latinos consider themselves a group? Do they cluster along lines of geographical origin? What is the relationship between old established settlements and new arrivals? How does the presence of 12 million undocumented ("illegal") arrivals affect the 25 million "legal" residents of the U.S. How has nativism and the hostility of Anglos and blacks shaped the group identity and opportunity? What impact is the rapid diffusion across the country having on local communities, schools, labor markets. Will the Latinos start voting in large numbers and become a political force? What is the impact of high dropout rates? Will majority-Latino communities change the national culture? Does Latino immigration follow or alter traditional patterns of assimilation? | The study of Latino history raises a issues regarding the definition and boundaries of "Latino." Are Latinos a "group" and if so, what are its defining boundaries and characteristics? Is speaking Spanish a requirement to be Latino? Are indigenous peoples from Latin America part of the group? Do Latinos consider themselves a group? Do they cluster along lines of geographical origin? What is the relationship between old established settlements and new arrivals? How does the presence of 12 million undocumented ("illegal") arrivals affect the 25 million "legal" residents of the U.S. How has nativism and the hostility of Anglos and blacks shaped the group identity and opportunity? What impact is the rapid diffusion across the country having on local communities, schools, labor markets. Will the Latinos start voting in large numbers and become a political force? What is the impact of high dropout rates? Will majority-Latino communities change the national culture? Does Latino immigration follow or alter traditional patterns of assimilation? | ||

== | ==Chicago== | ||

Fernandez (2005) documents the history of Mexican and Puerto Rican immigration and community formation in Chicago after World War II. Beginning with World War II, Mexican and Puerto Rican workers traveled to the Midwest through varying migrant streams to perform unskilled labor. They settled in separate areas of Chicago. These parallel migrations created historically unique communities where both groups encountered one another in the mid-twentieth century. By the 1950s and 1960s, both groups experienced repeated displacements and dislocations from the Near West Side, the Near North Side and the Lincoln Park neighborhood. At the macro level, Mexican and Puerto Rican workers' life chances were shaped by federal policies regarding immigration, labor, and citizenship. At the local level, they felt the impact of municipal government policies, which had specific racial dimensions. As these populations relocated from one neighborhood to the next, they made efforts to shape their own communities and their futures. During the period of the Civil Rights Movement, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans engaged in social struggles, both in coalition with one another but also as separate, distinct, national minorities. They created organizations and institutions such as Casa Aztlán , the Young Lords Organization, Mujeres Latinas en Acción , the Latin American Defense Organization, and El Centro de la Causa. These organizations drew upon differing strategies based on notions of nation, gender, and class, and at times produced inter-ethnic and inter-racial coalitions.<ref> Lilia Fernández, "Latina/o Migration and Community Formation in Postwar Chicago: Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Gender, and Politics, 1945-1975." PhD dissertation U. of California, San Diego 2005. 302 pp. DAI 2006 66(10): 3779-A. DA3191767 Fulltext: [[ProQuest Dissertations & Theses]]. See also Mérida M. Rúa, "Claims to `the City': Puerto Rican Latinidad amid Labors of Identity, Community, and Belonging in Chicago." PhD dissertation U. of Michigan 2004. 219 pp. DAI 2005 65(10): 3877-A. DA3150079 | |||

Fulltext: [[ProQuest Dissertations & Theses]]</ref> | |||

==Further reading== | |||

See the more detailed guide at the Bibliography subpage | |||

* Aranda, José, Jr. ''When We Arrive: A New Literary History of Mexican America.'' U. of Arizona Press, 2003. 256 pp. | * Aranda, José, Jr. ''When We Arrive: A New Literary History of Mexican America.'' U. of Arizona Press, 2003. 256 pp. | ||

* | * Bean, Frank D., and Marta Tienda. ''The Hispanic Population of the United States'' (1987), statistical analysis of demography and social structure | ||

* | * Bogardus, Emory S. ''The Mexican in the United States'' (1934), sociological | ||

* | * De León, Arnoldo. ''Mexican Americans in Texas: A Brief History'', 2nd ed. (1999) | ||

* | * De Leon, Arnoldo, and Richard Griswold Del Castillo. ''North to Aztlan: A History of Mexican Americans in the United States'' (2006) | ||

* Burt, Kenneth C. ''The Search for a Civic Voice: California Latino Politics,'' Regina Books, 2007. [http://www.amazon.com/gp/reader/1930053509/ref=sib_dp_bod_bc/103-4827826-5463040?ie=UTF8&p=S0CO#reader-link Excerpts and online search from Amazon.com] | * Burt, Kenneth C. ''The Search for a Civic Voice: California Latino Politics,'' Regina Books, 2007. [http://www.amazon.com/gp/reader/1930053509/ref=sib_dp_bod_bc/103-4827826-5463040?ie=UTF8&p=S0CO#reader-link Excerpts and online search from Amazon.com] | ||

* Dolan, Jay P. and Gilberto M. Hinojosa; ''Mexican Americans and the Catholic Church, 1900-1965'' (1994) | * Dolan, Jay P. and Gilberto M. Hinojosa; ''Mexican Americans and the Catholic Church, 1900-1965'' (1994) | ||

* | * García, María Cristina. ''Havana, USA: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959–1994'' (1996); [http://www.amazon.com/Havana-USA-Americans-Florida-1959-1994/dp/0520211170/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1197274078&sr=8-1 excerpt and text search] | ||

* | * Gomez-Quiñones, Juan. ''Mexican American Labor, 1790-1990.'' (1994). | ||

* Gomez-Quinones, Juan. ''Chicano Politics: Reality and Promise, 1940-1990'' (1990) | |||

* Gómez-Quiñones, Juan. ''Roots of Chicano Politics, 1600-1940'' (1994) | |||

* Gonzales-Berry, Erlinda, David R. Maciel, editors, ''The Contested Homeland: A Chicano History of New Mexico'', 314 pages (2000), ISBN 0-8263-2199-2 | |||

* Grebler, Leo, Joan Moore, and Ralph Guzmán. ''The Mexican American People: The Nation's Second Largest Minority'' (1970), emphasis on census data and statistics | |||

* Gutiérrez, David G. ed. ''The Columbia History of Latinos in the United States Since 1960'' (2004) 512pp[http://www.amazon.com/Columbia-History-Latinos-United-States/dp/0231118090/ref=sr_1_1/103-4827826-5463040?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1190386160&sr=8-1 excerpt and text search] | |||

* Gutiérrez, David G. "Migration, Emergent Ethnicity, and the "Third Space": The Shifting Politics of Nationalism in Greater Mexico" ''Journal of American History'' 1999 86(2): 481-517. [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8723(199909)86%3A2%3C481%3AMEEAT%22%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V in JSTOR] covers 1800 to the 1980s | |||

* Gutiérrez, David G. ''Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity in the Southwest, 1910-1986'' 1995. [http://www.amazon.com/Walls-Mirrors-Americans-Immigrants-Ethnicity/dp/0520202198/ref=sr_1_1/103-4827826-5463040?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1190439733&sr=8-1 excerpt and text search] | * Gutiérrez, David G. ''Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity in the Southwest, 1910-1986'' 1995. [http://www.amazon.com/Walls-Mirrors-Americans-Immigrants-Ethnicity/dp/0520202198/ref=sr_1_1/103-4827826-5463040?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1190439733&sr=8-1 excerpt and text search] | ||

* Gutiérrez; Ramón A. ''When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500-1846'' (1991) | * Gutiérrez; Ramón A. ''When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500-1846'' (1991) | ||

* [http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/index.html ''Handbook of Texas History'' Online] | * [http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/index.html ''Handbook of Texas History'' Online] | ||

* | * Meier, Matt S., and Margo Gutierrez, ed. ''Encyclopedia of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement'' (2000) [http://www.amazon.com/Encyclopedia-Mexican-American-Rights-Movement/dp/0313304254/ref=sr_1_2/103-4827826-5463040?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1190511642&sr=1-2 excerpt and text search] | ||

* Ruiz, Vicki L. “Nuestra América: Latino History as United States History,” ''Journal of American History,'' 93 (Dec. 2006), 655–72. | |||

* Ruiz, Vicki L. ''From Out of the Shadows: Mexican Women in Twentieth-Century America'' (1998) | |||

* Sãnchez Korrol, Virginia E. ''From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City.'' (1994) [http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2g5004p1/?&query=&brand=ucpress complete text online free in California]; [http://www.amazon.com/Colonia-Community-History-American-Society/dp/0520079000/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1197274120&sr=8-2 excerpt and text search] | |||

* Valle, Victor M. and Torres, Rodolfo D. ''Latino Metropolis.'' 2000. 249 pp. on Los Angeles | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* Weber, David J. ''The Mexican Frontier, 1821-1846: The American Southwest under Mexico'' (1982) | * Weber, David J. ''The Mexican Frontier, 1821-1846: The American Southwest under Mexico'' (1982) | ||

* Whalen, Carmen Teresa, and Victor Vásquez-Hernández, eds. '' The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Historical Perspectives'' (2005), | |||

=== | ====notes==== | ||

{{reflist}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

[[Category: | |||

Latest revision as of 11:00, 10 September 2024

Latino history is the history of Mexicans and other Hispanics in the United States from 1846 to the present. By 2005 the Latino population reached 41.3 million,of whom 64% were Mexican, 10% Puerto Rican, 3% Cuban, 3% Dominican, 3% Salvadoran, and the remaining 17% from smaller groups.[1] About 12 million undocumented ("illegal") immigrants live in the U.S., a number that has grown since the 9/11 attack of 2001.

19th century

When Mexico took over control from Spain in the early 1820s, the new government ignored and isolated the "norteños" (inhabitants of Mexico's northern provinces), except to break up the mission system in California (U.S. state). The systematic Navajo and Apache raids on New Mexico villages and ranches were ignored, as was the vulnerability of California, as the central government pulled back its soldiers to use them in recurrent civil wars and factional battles. When Texas seemed too independent, Mexico's President Santa Anna led an army to massacre the villagers and destroy the American settlements. After initial victories and massacres at The Alamo and Goliad, Santa Anna was decisively defeated by the Texans, who declared independence. The Tejanos in Texas joined the revolution and supported the new Republic of Texas; The Hispanics in New Mexico and California were localistic and did not identify with the regime in Mexico City. The "norteños" played a minor role in the Mexican American War of 1846-48, and when offered the choice of repatriating to Mexico or remaining and becoming full citizens of the United States, the great majority remained. Only when large numbers of Americans arrived did they develop a sense of "lo mexicano," that is of "being Mexican," and that new identification had little to do with far-off Mexico. [2] American entrepreneurs often cultivated alliances and partnerships with the Mexican propertied elites in the states of Texas and California, and the territories of New Mexico and Arizona. The Californios--who only numbered 10,000 in 1848, remained in California but were soon overwhelmed by the immigration of hundreds of thousands of newcomers to California, and largely became invisible to Anglos. The Latino culture of the rest of the Southwest, especially New Mexico and southern Texas, called itself "Spanish" (rather than "Mexican") to distinguish themselves from "los norteamericanos". The Latinos emphasized their own religion, language, customs and kinship ties, and drew into enclaves, rural colonies and urban barrios, which norteamericanos seldom entered; intermarriage rates were low.

20th century

After 1911 the ferocious civil wars in Mexico led 600,000 to 1 million refugees to flee north across the border, which was generally open. Well educated middle class families emigrated, as well as poor peons.

In Texas a band of radicals issued the manifesto "Plan de San Diego" in 1915 in South Texas calling on Hispanics to reconquer the Southwest and kill all the Anglo men. Rebels assassinated opponents and killed several dozen people in attacks on railroads and ranches before the Texas Rangers smashed the insurrection. Tejanos strongly repudiated the Plan and affirmed their American loyalty by founding the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). LULAC, headed by professionals, businessmen and modernizers, became the central Tejano organization promoting civic pride and civil rights.[3]

Over 500,000 returned after 1930, but many stayed. The consulates of the Mexican government in major cities in the Southwest organized a network of "juntas patrioticas" (patriotic councils) and "comisiónes honoríficos" (honorary committees) to celebrate Mexican national holidays such as the Cinco de Mayo; the target audience was the Latino middle class.[4]

In borderlands towns such as Brownsville, Corpus Christi, Laredo, San Antonio, El Paso, Tucson, Yuma, San Diego, and Los Angeles, local Latino leaders wanted to restrict the influx of immigrants, because the newcomers directly competed with resident Latinos for jobs and housing and because they reinforced negative stereotypes regarding a lazy and violent lifestyle. In 1929 the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was formed on the premise that full acceptance of American social, educational and political values was the only way Latinos could reasonably expect to improve their political, economic, and social position in American society. Some upwardly mobile families joined Protestant churches, but most remained devout, conservative Roman Catholics. From the early 1930s through the 1960s, LULAC's political agenda focused on citizenship training and naturalization of "foreign-born Mexicans," English-language training, active support of antidiscriminatory litigation and legislation (particularly regarding public schools), and strict control of further immigration from Mexico. LULAC promoted the liberal rhetoric of "equality" and "rights" and the mutual obligations of republican civic duty. However, voting levels were quite low, and especially in South Texas the Latino vote was controlled by local "bosses." There was little in the way of radical movements.

World War II

World War II was a watershed for all the Latino groups. Some 500,000 were drafted; even larger numbers of the women and older men worked in high paying munitions plants, ending the hardship years of the depression and inspiring demands for upward mobility and political rights. The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and El Congreso de Pueblos de Hablan Española (the Spanish-Speaking Peoples' Congress), founded before the war, expanded their membership and more successfully demanded full integration for their middle class constituents. Labor unions opened their membership rolls and Luisa Moreno became the first Latina to hold a national union office, as vice-president of the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), and affiliate of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

Post 1945

From 1945 to the early 1970s, large numbers of Latinos moved out of dead-end, low-wage work into higher-paying and higher-status skilled blue-collar occupations.[5] They and their children experienced steady gains in virtually all major socioeconomic indicators, including income, occupational status, English-language proficiency, years of education, and geographic mobility. The opportunities were in the cities; there was little upward mobility for those who remained in the California farmland or in the chronically depressed lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas, and in the isolated rural hamlets of Colorado and New Mexico.[6]

Seasonal migration

A common pattern emerged after 1940 of men working summers in the U.S. and spending the winter season in the village back in Mexico. While this became illegal in 1965, the numbers involved kept growing. By 2007 there were 12 million or so undocumented workers in the U.S.; they had jobs, often using fake identity cards. They made money in the U.S. but returned to the villages to spend it, attend fiestas, tend to family business, and participate in extended kinship rituals such as baptisms, weddings, and funerals. After the increased border security following the 9/11 attack in 2001, the back-and-forth pattern became dangerous. People kept coming north, but they stayed in the U.S. and sent money home every month. Locked into the American economy year-round, millions of these undocumented workers moved out of season agricultural jobs into year-round jobs in restaurants, hotels, construction, landscaping and semiskilled factory work, such as meat packing. Most paid federal social security taxes into imaginary accounts (and thus were not eligible for benefits.) Few had high enough incomes to pay federal or state income taxes, but all paid local and state sales taxes on their purchases as well as local property taxes (via their rent payments to landlords).

Politics

Latinos engaged in national politics for the first time in 1960 when hundreds of "Viva Kennedy" clubs were created. As a result of military service in World War II the slowly improving civil rights atmosphere of the 1950s, Mexican Americans had tasted some limited successes in access to employment, education (particularly through the benefits of the G.I. Bill), and the election of a few government officials at the state and local levels. Moreover, with the establishment of new, aggressive Mexican American advocacy organizations in the Southwest between 1947 and 1959, community activists symbolically announced that Mexican Americans would henceforth be a political force with which to reckon. About 85% of the Mexican American vote went to Kennedy, slightly higher than other Catholic ethnics. The Latinos took credit for carrying California and Texas by razor-thin margins. President Kennedy, however, made some symbolic appointments but showed minimal interest in Mexican American issues.

In 2000 and 2004 presidential elections, George W. Bush made a systematic effort to reach Latino voters, obtaining 40% of their vote. Most remained Democrats and in the 2008 presidential election, heavily favored Hillary Clinton over Barack Obama for the nomination.

Demography

California in 2006 had the largest Hispanic population of any state as of 2006 (13.1 million), followed by Texas (8.4 million) and Florida (3.6 million). Texas had the largest numerical increase between 2005 and 2006 (305,000), with California (283,000) and Florida (161,000) following. In New Mexico, Hispanics comprised the highest proportion of the total population (44%), with California and Texas (36% each) next in line. The Hispanic population in 2006 was much younger, with a median age of 27.4 compared with the population as a whole at 36.4. About a third of the Hispanic population was younger than 18, compared with one-fourth of the total population.[7]

The rapid growth of the Hispanic population after 1972 began in the Southwest, but spread nationwide by 2000. The diffusion of Latinos across the country was dramatic by 2008, and became a major issue in the presidential election, with Republicans echoing nativist hostilities. In Georgia, for example, there were barely 60,000 Latinos in 1980, and 100,000 in 1990, less than 2%. By the 2000 Census the number had surged to 435,000, or 5%, with continuing rapid growth to 700,000 in 2006.[8]

In 1972 Hispanics comprised 6% of public school students, and more than tripled to 20% in 2005. However, despite fears that assimilation would be difficult, the proportion of students who spoke English with difficulty has been flat at 5%, according to graph 1.

Puerto Ricans

The U.S. acquired Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898, and engaged in a massive modernization program involving disease control, sanitation, transportation, internal improvements, and medical care, along with corporate investment in sugar plantations. The island was overpopulated, so a systematic effort was made to assist migration. Over 5000 migrated to Hawaii (also acquired in 1898) to work in sugar plantations. By 1920 Puerto Ricans had full U.S. citizenship and had a presence in 45 states. New York City was the destination of 60%; children born anywhere on the mainland were dubbed "Nuyorican."[9]

Historiography

The study of Latino history raises a issues regarding the definition and boundaries of "Latino." Are Latinos a "group" and if so, what are its defining boundaries and characteristics? Is speaking Spanish a requirement to be Latino? Are indigenous peoples from Latin America part of the group? Do Latinos consider themselves a group? Do they cluster along lines of geographical origin? What is the relationship between old established settlements and new arrivals? How does the presence of 12 million undocumented ("illegal") arrivals affect the 25 million "legal" residents of the U.S. How has nativism and the hostility of Anglos and blacks shaped the group identity and opportunity? What impact is the rapid diffusion across the country having on local communities, schools, labor markets. Will the Latinos start voting in large numbers and become a political force? What is the impact of high dropout rates? Will majority-Latino communities change the national culture? Does Latino immigration follow or alter traditional patterns of assimilation?

Chicago

Fernandez (2005) documents the history of Mexican and Puerto Rican immigration and community formation in Chicago after World War II. Beginning with World War II, Mexican and Puerto Rican workers traveled to the Midwest through varying migrant streams to perform unskilled labor. They settled in separate areas of Chicago. These parallel migrations created historically unique communities where both groups encountered one another in the mid-twentieth century. By the 1950s and 1960s, both groups experienced repeated displacements and dislocations from the Near West Side, the Near North Side and the Lincoln Park neighborhood. At the macro level, Mexican and Puerto Rican workers' life chances were shaped by federal policies regarding immigration, labor, and citizenship. At the local level, they felt the impact of municipal government policies, which had specific racial dimensions. As these populations relocated from one neighborhood to the next, they made efforts to shape their own communities and their futures. During the period of the Civil Rights Movement, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans engaged in social struggles, both in coalition with one another but also as separate, distinct, national minorities. They created organizations and institutions such as Casa Aztlán , the Young Lords Organization, Mujeres Latinas en Acción , the Latin American Defense Organization, and El Centro de la Causa. These organizations drew upon differing strategies based on notions of nation, gender, and class, and at times produced inter-ethnic and inter-racial coalitions.[10]

Further reading

See the more detailed guide at the Bibliography subpage

- Aranda, José, Jr. When We Arrive: A New Literary History of Mexican America. U. of Arizona Press, 2003. 256 pp.

- Bean, Frank D., and Marta Tienda. The Hispanic Population of the United States (1987), statistical analysis of demography and social structure

- Bogardus, Emory S. The Mexican in the United States (1934), sociological

- De León, Arnoldo. Mexican Americans in Texas: A Brief History, 2nd ed. (1999)

- De Leon, Arnoldo, and Richard Griswold Del Castillo. North to Aztlan: A History of Mexican Americans in the United States (2006)

- Burt, Kenneth C. The Search for a Civic Voice: California Latino Politics, Regina Books, 2007. Excerpts and online search from Amazon.com

- Dolan, Jay P. and Gilberto M. Hinojosa; Mexican Americans and the Catholic Church, 1900-1965 (1994)

- García, María Cristina. Havana, USA: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959–1994 (1996); excerpt and text search

- Gomez-Quiñones, Juan. Mexican American Labor, 1790-1990. (1994).

- Gomez-Quinones, Juan. Chicano Politics: Reality and Promise, 1940-1990 (1990)

- Gómez-Quiñones, Juan. Roots of Chicano Politics, 1600-1940 (1994)

- Gonzales-Berry, Erlinda, David R. Maciel, editors, The Contested Homeland: A Chicano History of New Mexico, 314 pages (2000), ISBN 0-8263-2199-2

- Grebler, Leo, Joan Moore, and Ralph Guzmán. The Mexican American People: The Nation's Second Largest Minority (1970), emphasis on census data and statistics

- Gutiérrez, David G. ed. The Columbia History of Latinos in the United States Since 1960 (2004) 512ppexcerpt and text search

- Gutiérrez, David G. "Migration, Emergent Ethnicity, and the "Third Space": The Shifting Politics of Nationalism in Greater Mexico" Journal of American History 1999 86(2): 481-517. in JSTOR covers 1800 to the 1980s

- Gutiérrez, David G. Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity in the Southwest, 1910-1986 1995. excerpt and text search

- Gutiérrez; Ramón A. When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500-1846 (1991)

- Handbook of Texas History Online

- Meier, Matt S., and Margo Gutierrez, ed. Encyclopedia of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement (2000) excerpt and text search

- Ruiz, Vicki L. “Nuestra América: Latino History as United States History,” Journal of American History, 93 (Dec. 2006), 655–72.

- Ruiz, Vicki L. From Out of the Shadows: Mexican Women in Twentieth-Century America (1998)

- Sãnchez Korrol, Virginia E. From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City. (1994) complete text online free in California; excerpt and text search

- Valle, Victor M. and Torres, Rodolfo D. Latino Metropolis. 2000. 249 pp. on Los Angeles

- Weber, David J. The Mexican Frontier, 1821-1846: The American Southwest under Mexico (1982)

- Whalen, Carmen Teresa, and Victor Vásquez-Hernández, eds. The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Historical Perspectives (2005),

notes

- ↑ See Census Bureau press release, July 16, 2007 at [1]

- ↑ David G. Gutiérrez, "Migration, Emergent Ethnicity, and the "Third Space": The Shifting Politics of Nationalism in Greater Mexico" Journal of American History 1999 86(2): 481-517. ISSN: 0021-8723 in JSTOR

- ↑ Benjamin H. Johnson, Revolution in Texas: how a forgotten rebellion and its bloody suppression turned Mexicans into Americans. (2003).

- ↑ In Mexico itself, the emergence of a national identity for the average person was the work of the 20th century. After 1920 the national government promoted "true" mexicanismo by stirring up anti-American sentiment; promoting contemporary Mexican art, music, and literature; extolling and placing new emphasis on the value of the nation's indigenous peoples and the heritage of mestizaje. Gutiérrez (1999)

- ↑ 43% of the men were still unskilled workers or farm laborers in 1950; by 1960, the proportion had fallen to 33%.

- ↑ Bean and Tienda, The Hispanic Population of the United States (1987), 17-22, 280-337.

- ↑ See Census report May 17, 2007 at [2] with details at [3]

- ↑ Bullock and Hood (2006)

- ↑ Ruiz (2006)

- ↑ Lilia Fernández, "Latina/o Migration and Community Formation in Postwar Chicago: Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Gender, and Politics, 1945-1975." PhD dissertation U. of California, San Diego 2005. 302 pp. DAI 2006 66(10): 3779-A. DA3191767 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. See also Mérida M. Rúa, "Claims to `the City': Puerto Rican Latinidad amid Labors of Identity, Community, and Belonging in Chicago." PhD dissertation U. of Michigan 2004. 219 pp. DAI 2005 65(10): 3877-A. DA3150079 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses