Los Alamos National Laboratory: Difference between revisions

imported>Ro Thorpe mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (48 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Image|LANL site.jpg|right|300px|Aerial view of Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1995}} | {{Image|LANL site.jpg|right|300px|Aerial view of Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1995}} | ||

'''Los Alamos National Laboratory''' (LANL) is | '''Los Alamos National Laboratory''' (LANL), located in [[Los Alamos]], [[New Mexico (U.S. state)|New Mexico]], is one of several [[U.S. Department of Energy]] (DOE) national laboratories. It is noteworthy as the site where the first atomic weapon was developed under a heavy cloak of secrecy during [[World War II]], and has been known variously as '''''Site Y''''', '''''Los Alamos Laboratory''''', and '''''Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory'''''. Today, it is recognized as one of the world's leading science and technology institutes. | ||

LANL's | Since 2006, LANL has been managed and operated by [[Los Alamos National Security, LLC]] (LANS).<ref name=LANS/> | ||

LANL's self-stated mission is to ensure the safety, security, and reliability of the nation's nuclear deterrent.<ref name=LANL-Mission/> Its research work serves to advance [[Biology|bioscience]], [[chemistry]], [[computer science]], [[Earth science|earth]] and [[environmental science]]s, [[materials science]], and [[physics]] disciplines.<ref name=LANL-About/><ref name=LANL-Overview/> | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

===''World War II and the Manhattan Project''=== | ===''World War II and the Manhattan Project''=== | ||

{{Image|Trinity test.jpg|right|250px|Trinity test of an | {{Image|Trinity test.jpg|right|250px|Trinity test of an atomic bomb]] on July 15, 1945 at 0.016 seconds after detonation. The fireball was about 200 metres wide.}} | ||

The [[Manhattan Project]] was the secret [[United States]] project conducted primarily during [[World War II]] with the participation of the [[United Kingdom]] and [[Canada]] that culminated in developing the world's first | The [[Manhattan Project]] was the secret [[United States of America]] project conducted primarily during [[World War II]] with the participation of the [[United Kingdom]] and [[Canada]] that culminated in developing the world's first nuclear weapon, commonly referred to at that time as an ''atomic bomb''. | ||

The project was initiated in 1939 by [[U.S. President]] [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt]] after he received a letter from physicist [[Albert Einstein]] (drafted by fellow physicist [[Leó Szilárd]]) urging the study of [[nuclear fission]] for military purposes, under fears that [[Nazi Germany]] would be first to develop nuclear weapons. Roosevelt started a small investigation into the matter which eventually became the massive [[Manhattan Project]] that employed more than 130,000 people at universities across the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada as well as at the three major design, development and production facilities | The project was initiated in 1939 by [[U.S. President]] [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt]] after he received a letter from physicist [[Albert Einstein]] (drafted by fellow physicist [[Leó Szilárd]]) urging the study of [[nuclear fission]] for military purposes, under fears that [[Nazi Germany]] would be first to develop nuclear weapons. Roosevelt started a small investigation into the matter, which eventually became the massive [[Manhattan Project]] that employed more than 130,000 people at universities across the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada as well as at the three major design, development and production facilities: Los Alamos; Hanford, Washington; and Oak Ridge, Tennessee. | ||

The weapons design and development facility was headquartered at Los Alamos, New Mexico, which was known then as '''''Site Y''''', later to become the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. It was here that 90 eminent scientists (20 of whom were or later became Nobel Laureates)<ref name=Scientists/> from the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Hungary, Italy, and elsewhere worked to develop a workable atomic weapon. The scientific director of the Los Alamos site was the American physicist [[J. Robert Oppenheimer]]. The [[Hanford Site]] in eastern [[Washington (U.S. state)|Washington state]] was the [[plutonium]] production facility and the [[Oak Ridge, Tennessee]] site was the [[uranium]] enrichment facility. | |||

President Roosevelt died in mid-April 1945 and was succeeded by President [[Harry S. Truman]] just a few weeks before the war against [[Germany]] and [[Italy]] in [[Europe]] ended in May 1945. | President Roosevelt died in mid-April 1945 and was succeeded by President [[Harry S. Truman]] just a few weeks before the war against [[Germany]] and [[Italy]] in [[Europe]] ended in May 1945. | ||

The Manhattan project culminated with the detonation of the first nuclear weapon, known as the [[Trinity test]], | The Manhattan project culminated with the detonation of the first nuclear weapon, known as the [[Trinity test]], | ||

in July 1945 at [[White Sands]], [[New Mexico]]. Since [[Japan]] | in July 1945 at [[White Sands]], [[New Mexico (U.S. state)|New Mexico]]. Since the U.S. was still at war with [[Japan]] in the [[Pacific]], President Truman decided to use atomic bombs on Japanese cities. The atomic bombs were dropped by air on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. The Japanese surrendered shortly thereafter (August 14, 1945), and the war in the Pacific ended.<ref name=LANL-Overview/><ref name=HiroshimaBombing/> A formal surrender ceremony took place aboard the [[USS Missouri]] in [[Tokyo Bay]] on September 2, 1945.<ref name=TokyoBaySurrender/> | ||

===''Post World War II''=== | ===''Post World War II''=== | ||

As soon as the war ended, many of the scientists returned to their prewar universities. [[J. Robert Oppenheimer]], who had served as the Director of the Los Alamos site for the duration of the Manhattan project and the war, asked physicist [[Norris Edwin Bradbury]] to succeed him. Bradbury accepted and, during his | As soon as the war ended, many of the scientists returned to their prewar universities. [[J. Robert Oppenheimer]], who had served as the Director of the Los Alamos site for the duration of the Manhattan project and the war, asked physicist [[Norris Edwin Bradbury]] to succeed him. Bradbury accepted and, during his 1945–1970 tenure as Director, he became the acknowledged architect of the modern Los Alamos National Laboratory.<ref name=BradburyYears/><ref name=BradburyObituary/> | ||

A short four years later the [[Soviet Union]] detonated | A short four years later the [[Soviet Union]] detonated its first atomic bomb in August 1949. That event was viewed by the United States and its allies as a new peril facing the world and intensified the era of mutual distrust and antagonism between the Soviet Union and the United States that became known as the [[Cold War]], which lasted until 1991. | ||

The atomic bombs that had been developed by the end of 1949 were based on the energy released by [[nuclear fission]] reactions or, more simply, the splitting of atoms. Some research had already begun at the Los Alamos site by physicists [[Hans Bethe]] and [[Edward Teller]] as well as mathematician [[Stanislaw Ulam]] on what became known as [[Fusion device|thermonuclear]] weapons (also referred to as [[ | The atomic bombs that had been developed by the end of 1949 were based on the energy released by [[nuclear fission]] reactions or, more simply, the splitting of atoms. Some research had already begun at the Los Alamos site by physicists [[Hans Bethe]] and [[Edward Teller]] as well as mathematician [[Stanislaw Ulam]] on what became known as [[Fusion device|thermonuclear]] weapons (also referred to as [[hydrogen bomb]]s or [[H-bomb]]s). Thermonuclear weapons are based on the energy released by [[Fusion device|nuclear fusion]] reactions or, more simply, the fusion of atoms. | ||

A thermonuclear weapon generates vastly more energy, per unit of weight of the physical weapon, than does a pure fission bomb. In January | A thermonuclear weapon generates vastly more energy, per unit of weight of the physical weapon, than does a pure fission bomb. In January 1950, faced with the fact that the Soviet Union had successfully detonated an atomic bomb, President Truman announced that the United States was going to develop thermonuclear weapons of all kinds.<ref name=BradburyColleagues/> Almost three years later, on October 31, 1952 (local time), the United States detonated its first full-scale thermonuclear test device, code-named [[Operation Ivy|Ivy Mike]], on [[Enewetak Atoll]], located in the [[Marshall Islands]] of the Pacific Ocean. The test device was based on a design developed by Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam and it produced an energy yield of 10.4 megatonnes of [[TNT equivalent]],<ref name=TNTequiv group=note/> which was equal to the energy yield of 800 atomic bombs such as had been used on Hiroshima.<ref name=NucWpnsJournal/> The Ivy Mike thermonuclear device was specifically designed as a test device to validate the concept of creating a nuclear fusion weapon. It weighed about 74 [[tonne]]s (82 [[U.S. customary units|short tons]]) and was much too large and unwieldy to be used as a deliverable bomb or weapon.<ref name=NucWpnsJournal/> | ||

{{Image|Castle Bravo H-Bomb, 1954.jpg|left|230px|Fireball of Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test}} | {{Image|Castle Bravo H-Bomb, 1954.jpg|left|230px|Fireball of Castle Bravo 1 megaton hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll, March 1, 1954}} | ||

Two years later, the United States conducted | Two years later, the United States conducted its first test of a deliverable thermonuclear hydrogen bomb. The test was code-named [[Castle Bravo]] and it took place on March 1, 1954 (local time) on [[Bikini Atoll]] in the Marshall Islands of the Pacific Ocean. The bomb weighed 10.70 tonnes (11.75 short tons) and had an energy yield of 15 megatonnes of TNT equivalent. The Bravo crater in the atoll had a diameter of 1.98 km, with a depth of 76 m. Within one minute, the mushroom cloud had reached 15 km, breaking 30 km two minutes later. Eight minutes after the test the cloud had reached its full dimensions with a diameter of 100 km, a stem 7 km thick, and a cloud bottom rising above 16.5 km. It was the most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated by the United States.<ref name=NucWpnsJournal/><ref name=CastleBravo/> LANL played a major role in the design and construction of the thermonuclear test devices and bombs. | ||

The success of the Ivy Mike and Castle Bravo tests inaugurated a new era of developing smaller nuclear weapons having increased destructive power. From the mid-1950s until the early 1970s, the focus was upon miniaturizing the thermonuclear weapons to make them deliverable by aircraft and, later, to fit into long-range missiles.<ref name=LANL-Postwar/> | The success of the Ivy Mike and Castle Bravo tests inaugurated a new era of developing smaller nuclear weapons having increased destructive power. From the mid-1950s until the early 1970s, the focus was upon miniaturizing the thermonuclear weapons to make them deliverable by aircraft and, later, to fit into long-range missiles.<ref name=LANL-Postwar/> | ||

By the early | By the early 1970s, the focus on designing and building new weapons began to wane and the emphasis shifted to the stewardship and upgrading of the weapons already in the stockpile. It became important to make sure that nuclear weapons would only detonate on command and not by accident.<ref name=Accidents group=note/> Many of the underground nuclear tests conducted by the United States in the 1980s and early 1990s were safety tests of stockpiled weapons. With the current [[Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty|ban on nuclear weapon tests]], computer simulation and other methods are now used to ensure the safety of the stockpiled weapons.<ref name=LANL-Postwar/> | ||

Just exactly when LANL began to focus a significant part of | Just exactly when LANL began to focus a significant part of its work on scientific and technological fields other than nuclear weapons is not very clear. In 2010, 65 percent of LANL's annual expenditure was on weapons programs, working on nonproliferation of weapons, and maintaining security of equipment and information (see the section below on "Personnel and operating costs"). The remaining 35 percent of its expenditure was for scientific and technological fields other than nuclear weapons. | ||

The [[University of California]] has managed the Los Alamos Laboratory for much of the laboratory's history. However, in 2003 the Department of Energy opened the management contract up to other bidders. In June | The [[University of California]] has managed the Los Alamos Laboratory for much of the laboratory's history. However, in 2003 the Department of Energy opened the management contract up to other bidders. In June 2006 management of the laboratory was taken over by Los Alamos National Security, LLC, a private company of partners that include the University of California, [[Bechtel National Corporation]], [[Babcock & Wilcox Company]], and [[URS Corporation]].<ref name=LANS-2009Report/> | ||

==LANL Organization== | ==LANL Organization== | ||

Los Alamos National Laboratory is managed by Los Alamos National Security, LLC (LANS), which is a private limited liability company formed by the University of California, Bechtel National Corporation, Babcock & Wilcox Company, and URS Corporation. As agreed by the four LANS partners, a Board of Governors is charged with oversight and governance of LANS. The Board includes three individuals appointed by the University of California and three individuals appointed by Bechtel, as well as five independent Governors who are selected for their expertise and experience in fields pertinent to LANL operations. The Board includes an Executive Committee that consists of the six University of California and Bechtel appointees.<ref name=LANS-Board/> | |||

The President of LANS reports directly to the Board of Governors and also serves as the Director of Los Alamos National Laboratory. | The President of LANS reports directly to the Board of Governors and also serves as the Director of Los Alamos National Laboratory. | ||

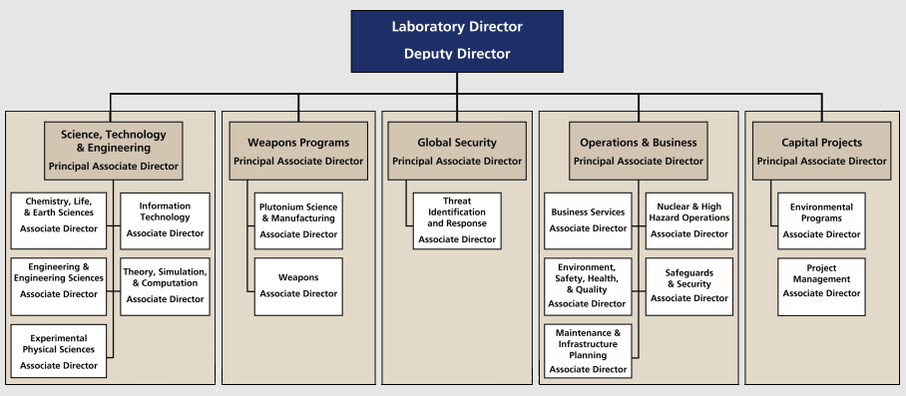

The day-to-day operations of LANL are led by its Director and a Deputy Director assisted by an Executive Director and an Executive Office Manager<ref name=OrgChart1/> | The day-to-day operations of LANL are led by its Director and a Deputy Director assisted by an Executive Director and an Executive Office Manager.<ref name=OrgChart1/> As shown in the organization chart below, five operating divisions, each headed by a Principal Associate Director, report to the Director's office:<ref name=OrgChart2/> | ||

{{Image|LANL Organization.png|center|906px|LANL Organization Chart}} | {{Image|LANL Organization.png|center|906px|LANL Organization Chart (as of 2011)<ref name=OrgChart2/>}} | ||

In addition, these twelve administrative functions report to the Director's office:<ref name=OrgChart1/> | In addition, these twelve administrative functions report to the Director's office:<ref name=OrgChart1/> | ||

| Line 64: | Line 61: | ||

* Community Programs Office | * Community Programs Office | ||

* Chief Prime Contracts | * Chief Prime Contracts | ||

* Office of Equal Opportunity | * Office of Equal Opportunity & Diversity | ||

* Ombudsman Office | * Ombudsman Office | ||

* Government & Community Affairs | * Government & Community Affairs | ||

| Line 99: | Line 96: | ||

LANL participates in a number of collaborative programs such as: | LANL participates in a number of collaborative programs such as: | ||

* | *LANL's ''Center for Nonlinear Studies'', in conjunction with the [[University of New Mexico]] and others, organizes the annual [[International q-bio Conference on Cellular Information Processing]] held at [[St. John's College]] in [[Santa Fe, New Mexico]]. The annual conferences are intended to advance predictive modeling of cellular regulation. The emphasis is on modeling and quantitative experimentation for understanding and predicting the behaviors of regulatory systems that occur in many biological systems, as well as the general principles of cellular information processing.<ref name=q-bio/> | ||

*The [[Joint Genome Institute]] (JGI) in [[Walnut Creek, California]], supported by the DOE Office of Science, combines the expertise of [[Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory]] (LBNL), [[Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory]] (LLNL), Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), [[Oak Ridge National Laboratory]] (ORNL), and [[Pacific Northwest National Laboratory]] (PNNL) as well as the [[HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology]] in [[Huntsville, Alabama]] to provide fundamental data on key [[gene]]s that may link to biological functions including microbial metabolic pathways and enzymes used to generate fuel molecules, affect plant biomass formation, degrade contaminants, or capture [[carbon dioxide]] (CO<sub>2</sub>).<ref name=JGI/> | *The [[Joint Genome Institute]] (JGI) in [[Walnut Creek, California]], supported by the DOE Office of Science, combines the expertise of [[Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory]] (LBNL), [[Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory]] (LLNL), Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), [[Oak Ridge National Laboratory]] (ORNL), and [[Pacific Northwest National Laboratory]] (PNNL) as well as the [[HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology]] in [[Huntsville, Alabama]] to provide fundamental data on key [[gene]]s that may link to biological functions including microbial metabolic pathways and enzymes used to generate fuel molecules, affect plant biomass formation, degrade contaminants, or capture [[carbon dioxide]] (CO<sub>2</sub>).<ref name=JGI/> | ||

*LANL operates one of the three [[National High Magnetic Field Laboratories]] (NHMFL) in collaboration with two other sites located at the [[Florida State University]] in [[Tallahassee, Florida]] and the [[University of Florida]] in [[Gainesville, Florida]]. The NHMFL operates state-of-the-art, high-magnetic field facilities for researchers and engineers. High magnetic fields are important to fundamental research in a diverse range of disciplines including biology, biochemistry, bioengineering, chemistry, engineering, geochemistry, materials science, medicine and physics.<ref name=NHMFL/> | *LANL operates one of the three [[National High Magnetic Field Laboratories]] (NHMFL) in collaboration with two other sites located at the [[Florida State University]] in [[Tallahassee, Florida]], and the [[University of Florida]] in [[Gainesville, Florida]]. The NHMFL operates state-of-the-art, high-magnetic field facilities for researchers and engineers. High magnetic fields are important to fundamental research in a diverse range of disciplines including biology, biochemistry, bioengineering, chemistry, engineering, geochemistry, materials science, medicine and physics.<ref name=NHMFL/> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

{{reflist|group=note|refs= | {{reflist|group=note|refs= | ||

<ref name=TNTequiv group=note>The yields of nuclear weapons are commonly expressed in units of ''TNT equivalent'', meaning the energy yield from the explosion of a stated amount of trinitrotoluene (TNT). The commonly used units are a kilotonne or a megatonne of TNT equivalent. A kilotonne (kt) of TNT equivalent is equal to 10<sup>12</sup> | <ref name=TNTequiv group=note>The yields of nuclear weapons are commonly expressed in units of ''TNT equivalent'', meaning the energy yield from the explosion of a stated amount of [[trinitrotoluene]] (TNT). The commonly used units are a kilotonne or a megatonne of TNT equivalent. A kilotonne (kt) of TNT equivalent is equal to 4.184 x 10<sup>12</sup> [[joule]]s and a megatonne (Mt) of TNT equivalent is equal to 4.184 x 10<sup>15</sup> joules. The kilotonne and megatonne are often taken to be synonymous with kiloton and megaton.</ref> | ||

<ref name=Accidents group=note>In 1966, a [[ | <ref name=Accidents group=note>In 1966, a [[United States Air Force]] [[B-52 Superfortress|B-52]] aircraft carrying four hydrogen bombs collided with a U.S. Air Force [[KC-135 Stratotanker|KC-135]] aircraft. The conventional explosives in two of the bombs detonated upon impact with the ground, dispersing plutonium over nearby farms. A third bomb landed intact near the coastal town of [[Palomares, Spain]], while the fourth fell 19 km off the coast into the [[Mediterranean Sea]]. In 1968, a B-52 aircraft crashed 11 km from the U.S. Air Force base at [[Thule, Greenland]]. The high-explosive detonators of four hydrogen bombs aboard the B-52 exploded and spread radioactive contamination over a 5-square-kilometre area of [[North Star Bay, Greenland]].</ref> | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 158: | Line 155: | ||

<ref name=BradburyColleagues>[http://www.lanl.gov/history/people/pdf/brad_remember.pdf Bradbury's colleagues remember his era] From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.</ref> | <ref name=BradburyColleagues>[http://www.lanl.gov/history/people/pdf/brad_remember.pdf Bradbury's colleagues remember his era] From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.</ref> | ||

}} | }}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:00, 13 September 2024

Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), located in Los Alamos, New Mexico, is one of several U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) national laboratories. It is noteworthy as the site where the first atomic weapon was developed under a heavy cloak of secrecy during World War II, and has been known variously as Site Y, Los Alamos Laboratory, and Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. Today, it is recognized as one of the world's leading science and technology institutes.

Since 2006, LANL has been managed and operated by Los Alamos National Security, LLC (LANS).[1] LANL's self-stated mission is to ensure the safety, security, and reliability of the nation's nuclear deterrent.[2] Its research work serves to advance bioscience, chemistry, computer science, earth and environmental sciences, materials science, and physics disciplines.[3][4]

History

World War II and the Manhattan Project

on July 15, 1945 at 0.016 seconds after detonation. The fireball was about 200 metres wide.]]

The Manhattan Project was the secret United States of America project conducted primarily during World War II with the participation of the United Kingdom and Canada that culminated in developing the world's first nuclear weapon, commonly referred to at that time as an atomic bomb.

The project was initiated in 1939 by U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt after he received a letter from physicist Albert Einstein (drafted by fellow physicist Leó Szilárd) urging the study of nuclear fission for military purposes, under fears that Nazi Germany would be first to develop nuclear weapons. Roosevelt started a small investigation into the matter, which eventually became the massive Manhattan Project that employed more than 130,000 people at universities across the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada as well as at the three major design, development and production facilities: Los Alamos; Hanford, Washington; and Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The weapons design and development facility was headquartered at Los Alamos, New Mexico, which was known then as Site Y, later to become the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. It was here that 90 eminent scientists (20 of whom were or later became Nobel Laureates)[5] from the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Hungary, Italy, and elsewhere worked to develop a workable atomic weapon. The scientific director of the Los Alamos site was the American physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. The Hanford Site in eastern Washington state was the plutonium production facility and the Oak Ridge, Tennessee site was the uranium enrichment facility.

President Roosevelt died in mid-April 1945 and was succeeded by President Harry S. Truman just a few weeks before the war against Germany and Italy in Europe ended in May 1945.

The Manhattan project culminated with the detonation of the first nuclear weapon, known as the Trinity test, in July 1945 at White Sands, New Mexico. Since the U.S. was still at war with Japan in the Pacific, President Truman decided to use atomic bombs on Japanese cities. The atomic bombs were dropped by air on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. The Japanese surrendered shortly thereafter (August 14, 1945), and the war in the Pacific ended.[4][6] A formal surrender ceremony took place aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945.[7]

Post World War II

As soon as the war ended, many of the scientists returned to their prewar universities. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who had served as the Director of the Los Alamos site for the duration of the Manhattan project and the war, asked physicist Norris Edwin Bradbury to succeed him. Bradbury accepted and, during his 1945–1970 tenure as Director, he became the acknowledged architect of the modern Los Alamos National Laboratory.[8][9]

A short four years later the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb in August 1949. That event was viewed by the United States and its allies as a new peril facing the world and intensified the era of mutual distrust and antagonism between the Soviet Union and the United States that became known as the Cold War, which lasted until 1991.

The atomic bombs that had been developed by the end of 1949 were based on the energy released by nuclear fission reactions or, more simply, the splitting of atoms. Some research had already begun at the Los Alamos site by physicists Hans Bethe and Edward Teller as well as mathematician Stanislaw Ulam on what became known as thermonuclear weapons (also referred to as hydrogen bombs or H-bombs). Thermonuclear weapons are based on the energy released by nuclear fusion reactions or, more simply, the fusion of atoms.

A thermonuclear weapon generates vastly more energy, per unit of weight of the physical weapon, than does a pure fission bomb. In January 1950, faced with the fact that the Soviet Union had successfully detonated an atomic bomb, President Truman announced that the United States was going to develop thermonuclear weapons of all kinds.[10] Almost three years later, on October 31, 1952 (local time), the United States detonated its first full-scale thermonuclear test device, code-named Ivy Mike, on Enewetak Atoll, located in the Marshall Islands of the Pacific Ocean. The test device was based on a design developed by Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam and it produced an energy yield of 10.4 megatonnes of TNT equivalent,[note 1] which was equal to the energy yield of 800 atomic bombs such as had been used on Hiroshima.[11] The Ivy Mike thermonuclear device was specifically designed as a test device to validate the concept of creating a nuclear fusion weapon. It weighed about 74 tonnes (82 short tons) and was much too large and unwieldy to be used as a deliverable bomb or weapon.[11]

Two years later, the United States conducted its first test of a deliverable thermonuclear hydrogen bomb. The test was code-named Castle Bravo and it took place on March 1, 1954 (local time) on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands of the Pacific Ocean. The bomb weighed 10.70 tonnes (11.75 short tons) and had an energy yield of 15 megatonnes of TNT equivalent. The Bravo crater in the atoll had a diameter of 1.98 km, with a depth of 76 m. Within one minute, the mushroom cloud had reached 15 km, breaking 30 km two minutes later. Eight minutes after the test the cloud had reached its full dimensions with a diameter of 100 km, a stem 7 km thick, and a cloud bottom rising above 16.5 km. It was the most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated by the United States.[11][12] LANL played a major role in the design and construction of the thermonuclear test devices and bombs.

The success of the Ivy Mike and Castle Bravo tests inaugurated a new era of developing smaller nuclear weapons having increased destructive power. From the mid-1950s until the early 1970s, the focus was upon miniaturizing the thermonuclear weapons to make them deliverable by aircraft and, later, to fit into long-range missiles.[13]

By the early 1970s, the focus on designing and building new weapons began to wane and the emphasis shifted to the stewardship and upgrading of the weapons already in the stockpile. It became important to make sure that nuclear weapons would only detonate on command and not by accident.[note 2] Many of the underground nuclear tests conducted by the United States in the 1980s and early 1990s were safety tests of stockpiled weapons. With the current ban on nuclear weapon tests, computer simulation and other methods are now used to ensure the safety of the stockpiled weapons.[13]

Just exactly when LANL began to focus a significant part of its work on scientific and technological fields other than nuclear weapons is not very clear. In 2010, 65 percent of LANL's annual expenditure was on weapons programs, working on nonproliferation of weapons, and maintaining security of equipment and information (see the section below on "Personnel and operating costs"). The remaining 35 percent of its expenditure was for scientific and technological fields other than nuclear weapons.

The University of California has managed the Los Alamos Laboratory for much of the laboratory's history. However, in 2003 the Department of Energy opened the management contract up to other bidders. In June 2006 management of the laboratory was taken over by Los Alamos National Security, LLC, a private company of partners that include the University of California, Bechtel National Corporation, Babcock & Wilcox Company, and URS Corporation.[14]

LANL Organization

Los Alamos National Laboratory is managed by Los Alamos National Security, LLC (LANS), which is a private limited liability company formed by the University of California, Bechtel National Corporation, Babcock & Wilcox Company, and URS Corporation. As agreed by the four LANS partners, a Board of Governors is charged with oversight and governance of LANS. The Board includes three individuals appointed by the University of California and three individuals appointed by Bechtel, as well as five independent Governors who are selected for their expertise and experience in fields pertinent to LANL operations. The Board includes an Executive Committee that consists of the six University of California and Bechtel appointees.[15]

The President of LANS reports directly to the Board of Governors and also serves as the Director of Los Alamos National Laboratory.

The day-to-day operations of LANL are led by its Director and a Deputy Director assisted by an Executive Director and an Executive Office Manager.[16] As shown in the organization chart below, five operating divisions, each headed by a Principal Associate Director, report to the Director's office:[17]

In addition, these twelve administrative functions report to the Director's office:[16]

|

|

Personnel and operating costs

As of May 2011 there were a total of 11,782 personnel in the Los Alamos National Laboratory with the following breakdown:[18]

- 9,685 Los Alamos National Security (LANS) personnel

- 477 contract guard force personnel

- 524 personnel working for various other contractors

- 1,116 students

The operating costs for the fiscal year of 2010 was about $2,000,000,000 with the following breakdown:[18]

- 51% for National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) weapons programs

- 8% for nonproliferation programs

- 11% for environmental management programs

- 4% for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science

- 5% for energy and other programs

- 6% for safeguards and security

- 15% for other work

Participation in collaborative programs

LANL participates in a number of collaborative programs such as:

- LANL's Center for Nonlinear Studies, in conjunction with the University of New Mexico and others, organizes the annual International q-bio Conference on Cellular Information Processing held at St. John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The annual conferences are intended to advance predictive modeling of cellular regulation. The emphasis is on modeling and quantitative experimentation for understanding and predicting the behaviors of regulatory systems that occur in many biological systems, as well as the general principles of cellular information processing.[19]

- The Joint Genome Institute (JGI) in Walnut Creek, California, supported by the DOE Office of Science, combines the expertise of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) as well as the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology in Huntsville, Alabama to provide fundamental data on key genes that may link to biological functions including microbial metabolic pathways and enzymes used to generate fuel molecules, affect plant biomass formation, degrade contaminants, or capture carbon dioxide (CO2).[20]

- LANL operates one of the three National High Magnetic Field Laboratories (NHMFL) in collaboration with two other sites located at the Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida, and the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida. The NHMFL operates state-of-the-art, high-magnetic field facilities for researchers and engineers. High magnetic fields are important to fundamental research in a diverse range of disciplines including biology, biochemistry, bioengineering, chemistry, engineering, geochemistry, materials science, medicine and physics.[21]

Notes

- ↑ The yields of nuclear weapons are commonly expressed in units of TNT equivalent, meaning the energy yield from the explosion of a stated amount of trinitrotoluene (TNT). The commonly used units are a kilotonne or a megatonne of TNT equivalent. A kilotonne (kt) of TNT equivalent is equal to 4.184 x 1012 joules and a megatonne (Mt) of TNT equivalent is equal to 4.184 x 1015 joules. The kilotonne and megatonne are often taken to be synonymous with kiloton and megaton.

- ↑ In 1966, a United States Air Force B-52 aircraft carrying four hydrogen bombs collided with a U.S. Air Force KC-135 aircraft. The conventional explosives in two of the bombs detonated upon impact with the ground, dispersing plutonium over nearby farms. A third bomb landed intact near the coastal town of Palomares, Spain, while the fourth fell 19 km off the coast into the Mediterranean Sea. In 1968, a B-52 aircraft crashed 11 km from the U.S. Air Force base at Thule, Greenland. The high-explosive detonators of four hydrogen bombs aboard the B-52 exploded and spread radioactive contamination over a 5-square-kilometre area of North Star Bay, Greenland.

References

- ↑ About LANS From the website of Los Alamos National Security, LLC.

- ↑ LANL History Overview] From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- ↑ About LANL From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Los Alamos Overview. From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- ↑ Manhattan Project Hall of Fame Directory From the website of the The Manhattan Project Heritage Preservation Association.

- ↑ The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima

- ↑ Tokyo Bay: The Formal Surrender of the Empire of Japan on Board USS Missouri, 2 September 1945 From the website of the Naval History & Heritage Command.

- ↑ The Bradbury Years, 1945 - 1970 Norris Bradbury was the architect of the modern Los Alamos National Laboratory. Bradbury served until his retirement in 1970. (From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory).

- ↑ Former Los Alamos Director Norris Bradbury dies Obituary and biography of Norris Edwin Bradbury, from the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- ↑ Bradbury's colleagues remember his era From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Nuclear Weapons Journal, Issue 1, 2006 Scroll down to pdf page 31 of 31 pages.

- ↑ Operation Castle: 1954 - Pacific Proving Ground Scroll down to "Castle Bravo" section.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Postwar World From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- ↑ 2009 LANS Board of Governors Report

- ↑ LANS Board of Governors

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Organization Chart 1 From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Organization Chart 2 From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Fast Facts From the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

- ↑ The Fifth Annual q-bio Conference on Cellular Information Processing

- ↑ The DOE Joint Genome Institute

- ↑ NSF-Supported Research Structure From the website of the National Science Foundation (NSF). Scroll down to pdf page 70 of 148 pages.