ThinkPad: Difference between revisions

John Leach (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Chinese" to "Chinese") |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

=== notes === | === notes === | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:01, 28 October 2024

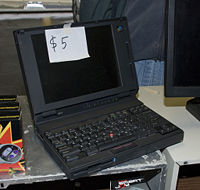

ThinkPad is a professional-oriented brand of laptop and tablet PCs from Lenovo. The product line was a part of the IBM's PC division that was sold to the Chinese company in 2005. The ThinkPad was first conceived as a dedicated tablet without a keyboard, but it emerged mainly as a notebook brand with the successful debut of the models 700 and 700C in October 1992. The 700/C and the subsequent ThinkPad models took the iconic shape of a black rectangular case and a keyboard featuring a red pointing device.

Creation Myth

The ThinkPad's beginning can be traced back to the 1980s when mobile computing was emerging in the form of microcomputers. The earliest form of mobile computing was the portable computer, which incorporated the keyboard and display into the main body in a more conveniently "transportable" package. Although the first portable computer was the IBM 5100 Portable Computer introduced in 1975,[1] it occupied only a small niche among engineers and analysts due to its hefty price tag that ranged from $9,000 to $20,000.[2] While IBM followed up the 5100 with the 5110 portable[3] and the desktop systems 5520 and 5120 from 1978 to 1980,[4][5] much of IBM's focus shifted back to its traditional mainframe business that was more profitable.[6]

The IBM PC

But it was precisely during this period when a new market developed for affordable "home/personal" computers that were up to several thousand dollars cheaper than their corporate counterparts. To be able to compete in this rapidly growing sector of the computing industry, IBM began development of a personal computer coded "Project Chess," which was tasked to a group of at least thirty members headed by P. Don Estridge. They were a skunk works type that tried what was never done before at IBM — an open architecture approach in collaboration with new start-ups Intel and Microsoft. Unlike other IBM products, the IBM PC was built on non-IBM, off-the-shell components and was open to third-party software,[9] as that would allow a shorter development period and result in a low-level entry product with less risk of cannibalizing the more powerful Display Writer.[10] At the time of the IBM PC's release to the public in August 1981, Apple, Commodore, and Tandy controlled 75% of the U.S. market. Although the IBM PC lacked obvious technological edge over the competition, it was able to gain foothold in the market and become the industry standard within 2 years due to IBM's dominant brand and extensive sales force.[6][11][12]

Compatibles & Portables

The PC's open hardware architecture which was part of its initial success also set the rise of competitors as others could apply the same third party components to build cloness that were compatible with the original through reverse engineering. The first and the most successful of these challengers was the Compaq Computer Corporation, which released the Compaq Portable in November 1982. At a price of $ 3,590, the Compaq Portable was not cheap by any means, but it became a success due to its "compact" and lightweight design.[13] The success of the Compaq Portable caught IBM off by surprise and provided the blueprint to success for other "IBM PC Compatible"s to follow. The consequent decline of the PC's market share prompted IBM to make entry into the portable market with the Portable Personal Computer (5155 model 68) in February 1984. Despite the high anticipations and the declines in stocks of competitors preceding its release, the 5155 was neither competitive in terms of the pricing nor the weight factor, providing the Compaq Portables a firm grip on its market dominance.[7]

The Portable PC's failure came in midst of the organizational turmoil that resulted from the restructuring of the IBM's microcomputing business as the executive team began to recognize the growing importance of the PC industry. Products such as the System/32 Datamaster and the IBM DisplayWrite were merged into the entry systems division, which was originally responsible for the Personal Computer, and its two laboratories at Boca Raton and Austin were made to work more closely together in terms of product planning and aligning of software and hardware. The ESD's pregnancy ended with the birth of the IBM PC Convertible at the IBM PC's fifth birthday party in August 1986. Although the Convertible weighed just 5.5 kg (less than 13 lbs) and could be carried by a built-in handle, it did not have a significant presence in the portable market due to its outdated components and lack of a modem. Its featuring the newer 3.5-inch drive also served as a minus for the product, since it would be incompatible with the 5.25-inch drive that was widely adopted. Even when more upgrades were made available to the PC Convertible, it remained outdated as the market moved beyond the "clamshell" form factor with the advent of full-fledged notebook PCs, such as the Compaq LTE and the NEC UltraLite.[14]

At this point, IBM could have easily withdrawn from the portable battle as its sales were a negligible portion of the entire PC market, but it did not "... because Compaq was now making a lot of money in portables and customers were asking for an all-IBM solution to their computing needs, [ and ] IBM executive management acknowledged the need for a portable computer in their product line."[15] The development of portables at IBM was continued by a small "skunksworks" team that was reminiscent of the original taskforce involved in "Project Chess." The team worked with the IBM's Yamato lab in Japan, which would come to play a crucial role in the later development of the ThinkPad. Code-named Aloha, the IBM Personal Systems/2 P70 was announced in May 1989, followed by the P75 486 in November 1990.

The portable market's shift to the notebook form factor also limited the success of the , which were among the last portables from IBM. The P70s were the product of the collaboration between the "skunksworks" team from the ESD and ThinkPad.

Birth of the ThinkPad

I wanted to create a volume as simple as possible and as expressive as possible... and I thought the form of a cigar box, which at that time corresponded to the dimensions... more or less than a laptop computer had to have, would be an expression of what I wanted to do. I wanted to make an object that looks like a black cigar box and that shows on the outside nothing of being what it is... except for the logo of the producer. Then, when you open it, you see this is not a cigar box, but it is a computer, and you see all the complicated stuff inside. And that would create a surprise, and this is the basic concept of the ThinkPad.

- Richard Sapper

Notable ThinkPads

Popular Legacy

notes

- ↑ Tech Republic staff. "Photos: Dinosaur Sightings: 1970s computers." cnet news. 12 Oct. 2007. Web. 12 Sept. 2009.

- ↑ "IBM 5100 Portable Computer." IBM Archives. IBM. Web. 12 Sept. 2009.

- ↑ "IBM 5110." IBM Archives. IBM. Web. 12 Sept. 2009.

- ↑ "IBM 5520." IBM Archives. IBM. Web. 12 Sept. 2009.

- ↑ "IBM 5120." IBM Archives. IBM. Web. 12 Sept. 2009.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Reilly, Edwin D. "IBM Corporation." The ACM Digital Library. University of Rochester. Web. 12 Sept. 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 SANDBERG-DIMENT, ERIK. "Advertise on NYTimes.com PERSONAL COMPUTERS; RIVALS STAY ONE STEP AHEAD OF I.B.M. PORTABLE." The New York Times 13 Mar. 1984. www.nytimes.com. Web. 12 Sept. 2009.

- ↑ Deborah and Purdy, 2000. pp. 19-39.

- ↑ "The History Of The IBM Personal Computer." COMPUTE MAGAZINE. 02 Mar. 2009. Web.

- ↑ Van, 2008. pp. 240.

- ↑ Taylor, Alexander L., and Frederick Ungeheuer. "IBM Is Homeward Bound." Time Magazine 24 Aug. 1981. Time. Web. 12 Sept. 2009.

- ↑ Moritz, Michael, and Alexander L. Taylor III. "Now No. 2, Apple Tries Harder." Time Magazine 26 Sept. 1983. TIME.COM. Time Inc. Web. 13 Sept. 2009.

- ↑ "Computer." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 12 Sep. 2009.

- ↑ Deborah and Purdy, 2000. pp 41-47.

- ↑ Deborah and Purdy, 2000. pp. 65.