Leidenfrost effect: Difference between revisions

imported>Charles Blackham mNo edit summary |

imported>Matt Mahlmann m (added wikilinks) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

:[[Image:Leidenfrost.PNG|frame|The Leidenfrost effect]] | :[[Image:Leidenfrost.PNG|frame|The Leidenfrost effect]] | ||

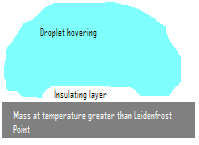

The Leidenfrost effect was first noted by Johann Gottlob Leidenfrost in 1756 in ''A Tract About Some Properties of Common Water''. The phenomenon occurs when a liquid drop comes into contact with a mass which is hotter than the Leidenfrost point (which is significantly greater than the boiling point) of the liquid. On hitting the mass, a thin insulating layer of vapour forms which dramatically slows the evaporation of the remainder of the droplet and it thus appears to hover over the plate as it slowly becomes smaller and smaller. The effect occurs due to the worse conduction of heat through a vapour than through liquid. | The '''Leidenfrost effect''' was first noted by Johann Gottlob Leidenfrost in 1756 in ''A Tract About Some Properties of Common Water''. The phenomenon occurs when a [[liquid]] drop comes into contact with a [[mass]] which is hotter than the [[Leidenfrost point]] (which is significantly greater than the [[boiling point]]) of the liquid. On hitting the mass, a thin insulating layer of vapour forms which dramatically slows the [[evaporation]] of the remainder of the droplet and it thus appears to hover over the plate as it slowly becomes smaller and smaller. The effect occurs due to the worse conduction of heat through a vapour than through liquid. | ||

The effect may be demonstrated at home by heating up a frying pan. If when drops of oil or water are sprinkled onto the surface they skitter across it as small balls, then the pan is hot enough - this is the Leidenfrost effect in action. It is also responsible fo one being able to put a wet hand into molten lead without burning it or take a mouthful of liquid nitrogen (without breathing it in, of course). | The effect may be demonstrated at home by heating up a frying pan. If when drops of oil or water are sprinkled onto the surface they skitter across it as small balls, then the pan is hot enough - this is the Leidenfrost effect in action. It is also responsible fo one being able to put a wet hand into molten lead without burning it or take a mouthful of liquid nitrogen (without breathing it in, of course). | ||

Revision as of 20:20, 17 April 2007

The Leidenfrost effect was first noted by Johann Gottlob Leidenfrost in 1756 in A Tract About Some Properties of Common Water. The phenomenon occurs when a liquid drop comes into contact with a mass which is hotter than the Leidenfrost point (which is significantly greater than the boiling point) of the liquid. On hitting the mass, a thin insulating layer of vapour forms which dramatically slows the evaporation of the remainder of the droplet and it thus appears to hover over the plate as it slowly becomes smaller and smaller. The effect occurs due to the worse conduction of heat through a vapour than through liquid.

The effect may be demonstrated at home by heating up a frying pan. If when drops of oil or water are sprinkled onto the surface they skitter across it as small balls, then the pan is hot enough - this is the Leidenfrost effect in action. It is also responsible fo one being able to put a wet hand into molten lead without burning it or take a mouthful of liquid nitrogen (without breathing it in, of course).

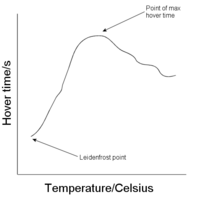

It may be seen how the Leidenfrost point varies for different liquids. It may be seen to rise as the carbon chain length increases in organic homologous series. For water it is about 230°C. It may also be observed how the time for which a droplet hovers (of a certain size) before having evaporated completely for a particular liquid. The temperature for which this time is a maximum follows the same trend as the Leidenfrost point for a homologous series.