Public goods: Difference between revisions

imported>Stephen Saletta (added externality section) |

imported>Caesar Schinas m (Bot: Update image code) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

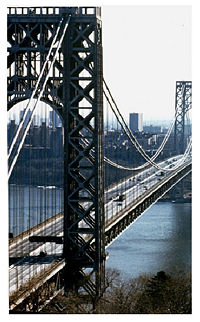

{{Image|Suspension bridge photo.jpg|right|200px|Bridges and roads are frequently classified as public goods.}} | |||

In [[economics]] the term '''public good''' is used to describe a service or commodity which is any commodity which is non-rivalrous and, to some extent, non-excludable.<ref>Pindyck, R and Rubinfeld, D (2001) ''Microeconomics'' ISBN 0130165832</ref> '''Non-rivalrous''' means that if one person is using the commodity, another individual may use it simultaneously without reducing the enjoyment the first person. A good example of a non-rivalrous commodity would be a radio station, because one person listening to his radio in the car doesn't prevent anyone else from listening to the same station. '''Non-excludable''' means that it is impossible (or very expensive) to exclude people from using the commodity. Clean air is an example of a non-excludable commodity because it would be very difficult to try and control how much air people breathe. | In [[economics]] the term '''public good''' is used to describe a service or commodity which is any commodity which is non-rivalrous and, to some extent, non-excludable.<ref>Pindyck, R and Rubinfeld, D (2001) ''Microeconomics'' ISBN 0130165832</ref> '''Non-rivalrous''' means that if one person is using the commodity, another individual may use it simultaneously without reducing the enjoyment the first person. A good example of a non-rivalrous commodity would be a radio station, because one person listening to his radio in the car doesn't prevent anyone else from listening to the same station. '''Non-excludable''' means that it is impossible (or very expensive) to exclude people from using the commodity. Clean air is an example of a non-excludable commodity because it would be very difficult to try and control how much air people breathe. | ||

Revision as of 07:47, 8 June 2009

In economics the term public good is used to describe a service or commodity which is any commodity which is non-rivalrous and, to some extent, non-excludable.[1] Non-rivalrous means that if one person is using the commodity, another individual may use it simultaneously without reducing the enjoyment the first person. A good example of a non-rivalrous commodity would be a radio station, because one person listening to his radio in the car doesn't prevent anyone else from listening to the same station. Non-excludable means that it is impossible (or very expensive) to exclude people from using the commodity. Clean air is an example of a non-excludable commodity because it would be very difficult to try and control how much air people breathe.

Public goods and externalities

The study of public goods is intimately linked to the economic concept of [externality]. An [externality] can be thought of as an extra benefit (or cost) provided to others that results from some activity which may or may not be related to the externality. One example of an externality is the Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) system which individuals can use to help find their way in a new city or out in the wilderness. The original purpose of GPS was to provide navigation and targeting capabilities to the U.S. military. However, once the satellites were in orbit to provide the service to the military, consumer electronics firms started making GPS devices for everyday civilian use. The benefit provided to people around the globe who can find their way with GPS is an example of an externality, because it is a spillover benefit, or side-effect resulting from the GPS program implemented to benefit the military.

An externality can also be something as simple as the enjoyment neigbors derive from a homeowner who keeps a neat lawn and garden. In this case the homeowner spends time and effort on mowing, fertilizer, etc... and neighbors derive utility in the form of higher property values, and their own enjoyment of living in a more aesthetically pleasing environment.

Externalities can be positive as well as negative. A good example of a negative externality is soot from a factory that makes it hard for people to breathe. The key feature of an externality is the difference between what the provider pays, and what the public receives. In the case of GPS, there is additional value provided to everyone who owns a GPS device not to mention the firms that produce and sell them at a profit) above and beyond what the US government pays for the value provided to the military, and in the case of pollution, the factory does not pay for the value of clean air that is lost by individuals who are affected by the soot.

Economic theory generally holds that if a good or service that conveys a positive externality, it will be underprovided. What this means is that individuals who value the externality would pay to get more of it than is provided at the market equilibrium.

The free-rider problem and the Tragedy of the Commons

In most cases, when people want more of something and are willing to pay for it, the market generally responds by increasing production. In the case of those goods which are non-excludable, it may be difficult if not impossible for people to voluntarily pay for something which they can get for free.

Conclusion

While a pure public good is strictly non-rivalrous and non-excludable, the more general usage of the term is that public goods should conform to both properties to a reasonable extent. For example if everyone tries to use a bridge at the same time, there will be a traffic jam, but the bridge is still considered a public good because once it has been built so that one person can use it, the marginal cost of allowing everyone to use it is zero.[2] Similarly, a tollbooth can be constructed to exclude people from using the bridge. Strictly speaking a bridge is a marketable public good or club good, but because of the expense involved in collecting tolls, many bridges are operated by the government as public goods.

References

- ↑ Pindyck, R and Rubinfeld, D (2001) Microeconomics ISBN 0130165832

- ↑ Hirshleifer, J and Hirshleifer, D (1997) Price Theory and Applications ISBN 0131907786