Telescope: Difference between revisions

imported>Thomas Simmons |

imported>Thomas Simmons |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

He published a number of works during his lifetime that clearly established him as a mathematician and student of astronomy with a pronounced ability in application but his achievements were expanded and revised by his son Thomas and published after Leonard's death, some of the work for the first time. Historically, it is difficult to separate the works of Leonard and Thomas due to the manner in which Thomas edited and published his father's works. | He published a number of works during his lifetime that clearly established him as a mathematician and student of astronomy with a pronounced ability in application but his achievements were expanded and revised by his son Thomas and published after Leonard's death, some of the work for the first time. Historically, it is difficult to separate the works of Leonard and Thomas due to the manner in which Thomas edited and published his father's works. | ||

There is clear evidence that he and his son Thomas did understand the design and function of telescopes. However the only evidence that Leonard actually used a telescope is offered by his son Thomas. For this reason, Hans Lipperhey is credited by many authorities with having invented the telescope | There is clear evidence that he and his son Thomas did understand the design and function of telescopes. However the only evidence that Leonard actually used a telescope is offered by his son Thomas. For this reason, Hans Lipperhey is credited by many authorities with having invented the telescope.<ref name=Gribbin>Gribbin, J. (2002) Science: A history. London: Penguin</ref><ref name=JohnstonDigges>[http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/staff/saj/thesis/digges.htm Thomas Digges: Gentleman and mathematician] Stephen Johnston (1994) chapter 2 (pp. 50-106) of, ‘Making mathematical practice: gentlemen, practitioners and artisans in Elizabethan England’ Ph.D. thesis, Cambridge. Available through University of Oxford, Museum of History of Science</ref><ref name=MacTutorThosDigges>[http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Digges.html Thomas Digges] O'Connor, J. J. and Robertson, E. F. (2002) MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, School of Math and Statistics, University of St. Andrews.</ref><ref>[http://galileo.rice.edu/Catalog/NewFiles/digges_leo.html Leonard Digges] Richard S. Westfall, Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Indiana University for the Galileo Project, Rice University</ref><ref name=RonanDiggesBJAA>[http://www.chocky.demon.co.uk/oas/diggeshistory.html Did the reflecting telescope have English origins?] Colin A Ronan (1991). ''Leonard and Thomas Digges.'' Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 101, 6</ref> | ||

===Thomas Digges (1543-1595)=== | ===Thomas Digges (1543-1595)=== | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Thomas’s publication, ''Alae seu scalae mathematicae'', in 1573, was a Latin text prompted by the new star of 1572, a supernova.<ref> sometimes referred to as ''Tycho's Supernova'' See reference to NASA/ESA Space Telescope cited below.</ref> Thomas's observations were employed by Tycho Brahe in his work. The supernova created quite a stir worldwide and certainly in Europe. There was a tremendous increase in astronomical and astrological work and publications. Tycho Brahe's supernova was significant because it encouraged astronomers in the 16th-century to question their perception that the heavans were immutable, that is, unchanging. Thomas's contribution was to determined the nova's position and his conclusion that its appearance was a challenge to traditional cosmology of the day. | Thomas’s publication, ''Alae seu scalae mathematicae'', in 1573, was a Latin text prompted by the new star of 1572, a supernova.<ref> sometimes referred to as ''Tycho's Supernova'' See reference to NASA/ESA Space Telescope cited below.</ref> Thomas's observations were employed by Tycho Brahe in his work. The supernova created quite a stir worldwide and certainly in Europe. There was a tremendous increase in astronomical and astrological work and publications. Tycho Brahe's supernova was significant because it encouraged astronomers in the 16th-century to question their perception that the heavans were immutable, that is, unchanging. Thomas's contribution was to determined the nova's position and his conclusion that its appearance was a challenge to traditional cosmology of the day. | ||

<ref name=Gribbin>Gribbin, J. (2002) Science: A history. London: Penguin</ref><ref name=JohnstonDigges/><ref name=MacTutorThosDigges/><ref>[http://galileo.rice.edu/Catalog/NewFiles/digges_tho.html Thomas Digges] Richard S. Westfall, Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Indiana University for the Galileo Project, Rice University</ref><ref>[http://www.spacetelescope.org/news/html/heic0415.html heic0415: Stellar survivor from 1572 A.D.] NASA/ESA Space Telescope. On Nov. 11, 1572, Tycho Brahe observed a star in the constellation Cassiopeia as bright as Jupiter which eventually equaled Venus in brightness. It was visible during daylight for about two weeks and eventually faded from unaided view altogether after about 16 months.</ref><ref name=RonanDiggesBJAA/> | <ref name=Gribbin>Gribbin, J. (2002) Science: A history. London: Penguin</ref><ref name=JohnstonDigges/><ref name=MacTutorThosDigges/><ref>[http://galileo.rice.edu/Catalog/NewFiles/digges_tho.html Thomas Digges] Richard S. Westfall, Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Indiana University for the Galileo Project, Rice University</ref><ref>[http://www.spacetelescope.org/news/html/heic0415.html heic0415: Stellar survivor from 1572 A.D.] NASA/ESA Space Telescope. On Nov. 11, 1572, Tycho Brahe observed a star in the constellation Cassiopeia as bright as Jupiter which eventually equaled Venus in brightness. It was visible during daylight for about two weeks and eventually faded from unaided view altogether after about 16 months.</ref><ref name=RonanDiggesBJAA/> | ||

===Hans Lipperhey=== | |||

Lipperhey (or Lippershey) was a Dutch spectacle maker who filed a patent for the refractive telescope in 1608. At that time there were several other patents pending. Lepperhey was apparently employed to make two lenses, one convex and the other concave. When the client appeared to take possession of the lens he positioned them to show how they magnified distant objects when used in tandem. Another claimant to the patent was the son of Sacharias Janssen. Janssen later noted that his father already had a telescope of Italian manufacture, dated 1590. These events predate Lipperhey’s claims.<ref name=RonanDiggesBJAA/> | |||

===[[Galileo Galilei]]=== | ===[[Galileo Galilei]]=== | ||

Revision as of 21:54, 22 March 2008

The word "telescope" comes from two Greek words: tele (τηλε)[1] meaning “far” or “distant”, and skopein (σκοπειν) meaning “to see.” Together they simply mean “to see from far away.[2]

A simple description of telescope is an instrument designed to magnify distant objects so that they can be viewed more easily. Telescopes historically have been constructed of lenses and mirrors which concentrate visible light into a smaller and more defined image.[3]

History of the development of the telescope

Leonard Digges (1520-1559)

Leonard Digges was a writer of mathematics and science in English, one of the first people to popularise work in either field. He was also a surveyor who invented the theodolite, the telescope, the reflecting telescope and possibly the refractive telescope a considerable amount of time before Galileo ever heard of telescopes. His influences in turn may predate his work by about 300 years because there is reason to believe that he encountered Roger Bacon's Opus Majus, (ca 1267) in the library of a friend, John Dee, and learned how lenses could be used to change the appearance of distant objects, specifically the Sun, Moon and stars.

He published a number of works during his lifetime that clearly established him as a mathematician and student of astronomy with a pronounced ability in application but his achievements were expanded and revised by his son Thomas and published after Leonard's death, some of the work for the first time. Historically, it is difficult to separate the works of Leonard and Thomas due to the manner in which Thomas edited and published his father's works.

There is clear evidence that he and his son Thomas did understand the design and function of telescopes. However the only evidence that Leonard actually used a telescope is offered by his son Thomas. For this reason, Hans Lipperhey is credited by many authorities with having invented the telescope.[4][5][6][7][8]

Thomas Digges (1543-1595)

In 1571, Thomas Digges published Leonard Digges's book on the telescope, Pantometria, twelve years after his father's death. Panometria was the first publications to discuss the invention of the telescope in English. Thomas had extended, revised and enhanced the book and he wrote the preface. J J O'Connor and E F Robertson note that while the description of how lenses could be combined to construct a telescope, there is no known evidence that the Diggeses did actually make a telescope and use one. Some authorities take exception to this view and regard the issue to be resolved. How is that the Diggeses knew how to construct a telescope and yet did not? Having constructed a telescope how is it they would not have used it? In his preface to the Pantometria, Thomas notes specifically how his father had observed things on numerous occasions from a considerable distance and with witnesses present. It is clear evidence to some authorities that Thomas he was describing a telescope that had indeed been constructed and used. The absence of specific notes on the use of a telescope are therefore not to be regarded as proof that the Diggeses, father and son, never made nor used a telescope.

Colin Ronan and Gilbert Satterthwaite built a telescope from a description provided in a report on military and naval inventions, written in 1578 William Bourne, for Lord Burghley, Elizabeth I's Secretary of State. Essentially it is noted as an invention that predates the claims for the invention by the Hans Lipperhey by about 30 years. Considering that the Pantometria was published 12 years after Leonard's death it is not unreasonable to assume that the telescope may have been invented by as much if not more than a half century before Hans Lipperhey.

Thomas’s publication, Alae seu scalae mathematicae, in 1573, was a Latin text prompted by the new star of 1572, a supernova.[9] Thomas's observations were employed by Tycho Brahe in his work. The supernova created quite a stir worldwide and certainly in Europe. There was a tremendous increase in astronomical and astrological work and publications. Tycho Brahe's supernova was significant because it encouraged astronomers in the 16th-century to question their perception that the heavans were immutable, that is, unchanging. Thomas's contribution was to determined the nova's position and his conclusion that its appearance was a challenge to traditional cosmology of the day. [4][5][6][10][11][8]

Hans Lipperhey

Lipperhey (or Lippershey) was a Dutch spectacle maker who filed a patent for the refractive telescope in 1608. At that time there were several other patents pending. Lepperhey was apparently employed to make two lenses, one convex and the other concave. When the client appeared to take possession of the lens he positioned them to show how they magnified distant objects when used in tandem. Another claimant to the patent was the son of Sacharias Janssen. Janssen later noted that his father already had a telescope of Italian manufacture, dated 1590. These events predate Lipperhey’s claims.[8]

Galileo Galilei

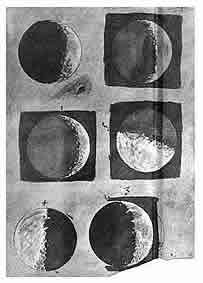

Galileo first heard of the telescope in 1609 and was able construct his own model from the description given him about the device patented by a spectacle maker in the Netherlands, Hans Lipperhey. He made several models including an 8-power telescope and a 20-power.[12] Galileo went on to make observations of the Moon, the Sun, the planets and stars [13]

Types of telescopes

References

- ↑ for example, télothen (τηλóθν), “from a distance” télourós (τηλουρóς), “far off.”

- ↑ [1], [2] & [3] S.C. Woodhouse (1910) Woodhouse's English-Greek Dictionary, The University of Chicago Library

- ↑ [4] from World Book at NASA for students adapted from "Telescope." The World Book Student Discovery Encyclopedia. Chicago: World Book, Inc., 2005.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gribbin, J. (2002) Science: A history. London: Penguin

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Thomas Digges: Gentleman and mathematician Stephen Johnston (1994) chapter 2 (pp. 50-106) of, ‘Making mathematical practice: gentlemen, practitioners and artisans in Elizabethan England’ Ph.D. thesis, Cambridge. Available through University of Oxford, Museum of History of Science

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Thomas Digges O'Connor, J. J. and Robertson, E. F. (2002) MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, School of Math and Statistics, University of St. Andrews.

- ↑ Leonard Digges Richard S. Westfall, Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Indiana University for the Galileo Project, Rice University

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Did the reflecting telescope have English origins? Colin A Ronan (1991). Leonard and Thomas Digges. Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 101, 6

- ↑ sometimes referred to as Tycho's Supernova See reference to NASA/ESA Space Telescope cited below.

- ↑ Thomas Digges Richard S. Westfall, Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Indiana University for the Galileo Project, Rice University

- ↑ heic0415: Stellar survivor from 1572 A.D. NASA/ESA Space Telescope. On Nov. 11, 1572, Tycho Brahe observed a star in the constellation Cassiopeia as bright as Jupiter which eventually equaled Venus in brightness. It was visible during daylight for about two weeks and eventually faded from unaided view altogether after about 16 months.

- ↑ Drake, Stillman (1973). "Galileo's Discovery of the Law of Free Fall". Scientific American v. 228, #5: 84-92

- ↑ Galilei, Galileo (1610). The Starry Messenger (Sidereus Nuncius). In Drake (1957):22-58