Battle of Iwo Jima: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz (work in progress; previously had been vignettes less context) |

imported>Caesar Schinas m (Robot: Changing template: TOC-right) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{TOC | {{TOC|right}} | ||

{{main|World War II, Pacific}} | {{main|World War II, Pacific}} | ||

Revision as of 04:13, 31 May 2009

The battle of Iwo Jima in February 1945, was a victory by 70,000 American Marines over 22,000 Japanese defenders of a small island in the Western Pacific. The battle became iconic in America as the epitome of heroism in desperate hand-to-hand combat:

Among the men who fought on Iwo Jima, uncommon valor was a common virtue.

—

Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas

Iwo Jima was a small island (only 8 square miles) on the route of the B-29s from Saipan to Japan. Airfields there could provide emergency landing fields for stricken Superfortresses, so Admiral Chester Nimitz ordered United States Fifth Fleet to take it; the invasion was code named "Operation Detachment;" the CINCPAC Operation Plan was No. 11-44. Following a massive naval and air bombardment, 70,000 Marines landed on February 19, 1945.

U.S. strategic justification

Nimitz's major stated goal was to use Iwo Jima as an escort fighter base against the Japanese home islands.[1] In practice, it turned out to be an emergency landing field for damaged B-29s.

To Japan, which considered Iwo Jima part of metropolitan Japan, administered by the Tokyo metropolitan government, it would be a psychological blow: the first foreign invasion of Japan in 4000 years. It also meant that attacks on Okinawa and Japan itself were near. No foreign army had set foot on Japanese soil in 4000 years. Additionally, the loss of Iwo Jima would mean that the battle for Okinawa, and the invasion of Japan itself, was not far off.[2]

Operational context

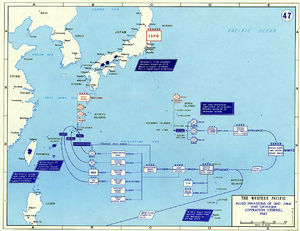

ADM Raymond Spruance, commanding United States Fifth Fleet's Operation Plan No. 13-44 of 31 December 1944 [1]. The Iwo and Okinawa operations were closely linked, as well as the immediately preceding Phillipines operations.

Preparing for Okinawa

Since land-based aircraft would be a major threat to the Okinawa operation, planned for April 1, any attrition to that threat, by the Iwo Jima landing scheduled for February 19, would support both operations. Not only were the battles themselves relevant, but Japanese aircraft production became a high bombing priority. Airbases on the Japanese island of Kyushu would also be attacked.

Carriers scheduled for Iwo Jima needed to be ready to start operations against Kyushu on 18 March and on Okinawa on 23 March.

U.S. Preparations

Spruance, in overall command, established the following organization:

- Joint Expeditionary Force (TF 51)--Vice Admiral R.K. Turner

- Attack Force (TF 53)--Rear Admiral H.W. Hill (also deputy to Turner)

- Fast Carrier Force (TF 58)--Vice Admiral M.A. Mitscher

- Expeditionary Troops (TF 56)--Lt. Gen. [[Holland M. Smith|H.M. "Howlin' Mad" Smith]

- The 54th Amphibious Corps was commanded by Major General Harry Schmidt:

- 3rd Marine Division (MG Graves B. Erskine)

- 4th Marine Division (MG Clifton B. Cates)

- 5th Marine Division (MG Keller E. Rockey)

- Amphibious Support Force (TF 52)--Rear Admiral W.H.P. Blandy.

- Logistic Support Group (TG 50.8)--Rear Admiral D.B. Beary.

- Search and Reconnaissance Group (TG 509.5)--Commodore D. Ketcham.

- Service Squadron 10 (TG 50.9)--Commodore W.R. Cater.

Japanese preparations

Lt. General Tadamichi Kuribayashi was ready with his 21,000 soldiers (far more than expected). His strategy was not to win, but to make the Yankees suffer far more than they could endure. He took advantage of the volcanic island's thousand caves and an ample supply of concrete, to build a vast underground defensive network interconnected by deep tunnels. His hidden artillery, mortars and machine guns survived the bombardment and stunned wave after wave of oncoming Marines. Each pillbox in a mutually-supportive grouping had to be destroyed by frontal assault.

Pre-landing bombardment

Iwo Jima received the heaviest air and naval bombardment of any objective in the Pacific. [3] While the preparation certainly damaged the Japanese, many of their installations were deeply buried, and effectively immune from the types of weapons used.

Marine commanders asked for a longer Naval preparation than was provided; the Navy rationale for not granting the request was: The Navy's major considerations in turning down Marine requests may be summarized as follows:

- "The initial surface bombardment must be simultaneous with the first carrier attack upon the Tokyo area by the Fast Carrier Force (TF 58). The carrier attacks were to continue for three days but unforeseen conditions might force TF 58 to withdraw earlier. Therefore, if preparation fires at Iwo commenced on D-minus-4 and the carriers were forced to abandon their operations against the Empire in two days or less, the enemy would have sufficient time to recover and launch air attacks against United States invasion shipping off Iwo Jima.

- The limitations on the availability of ships, difficulty in replenishing ammunition, and loss of surprise interposed serious obstacles to a protracted preparation.

- The Navy plan for three days of firing would accomplish all the desired objectives.

- The prolonged air bombardment might be considered at least as effective as one day of additional surface bombardment"[4]

Landings

After the grueling experience of cave warfare on other islands such as Peleliu, the Marines were ready with new tactics and new weapons, especially "bazooka" man-portable rocket-launchers using shaped charges, and both backpack and tank-mounted flame throwers.

2nd Battalion, 27th Marine Regiment (2/27 Marines), part of the 5th Marine Division, landed on Beach Red 2 on D-Day and spent 17 days and nights in combat. Of its 954 men, 216 were killed, 538 wounded, and 94 others were evacuated for sickness. Only 106 survived unscathed.

On D+4 the 28th Marines planted the Stars and Stripes on Mount Suribachi; watching in awe, Navy Secretary James Forrestal exclaimed that this dramatic moment guaranteed "there will be a Marine Corps for the next 500 years!" Associated Press reporter Joe Rosenthal's photograph of six soldiers raising the American flag on February 23, 1945 is often cited as the most reproduced photograph of all time. (It was not faked or staged.) The photograph become the archetypal representation not only of that battle, but of the entire Pacific war. Of the six soldiers in Rosenthal's photo, only three survived the battle.

The Japanese fought to the last man, killing 6,000 Marines and wounding 20,000 more. Seven Marines won the Medal of Honor by throwing themselves atop grenades to save their comrades; a total of 27 American fighting men received this highest direction for valor. Japanese analysis of the battle, and American public opinion, suggested their most effective strategy would be to inflict maximum casualties.

The iconic memory of Iwo Jima comprises the flag raising ceremony and memories of combat; the Japanese perspective was brought vividly to life in the film by Clint Eastwood, Letters from Iwo Jima (2007). The flag raising is often a theme in editorial cartoons, including both calls for heroism and parodies.[5]

Controversies

Should Iwo Jima have been bypassed? Over 25,000 airmen eventually made emergency landings on Iwo, but most would have survived without the island. It was also possible to launch fighter and reconnaissance sorties from the island, but the necessity was questioned. The subsequent nuclear attack missions flew from Tinian.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff had recommended the use of chemical weapons on Iwo Jima, prior to the landing. Franklin D. Roosevelt personally refused the request, which could have killed Japanese that survived conventional warfare. There certainly would have been political and propaganda consequences from the U.S. making first use of chemical weapons, although it is not clear that the Axis powers could have made effective retaliatory use.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Headquarters of the Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, I. Narrative, Amphibious Operations: Capture of Iwo Jima, 16 February to 16 March 1945, COMINCH P-0012

- ↑ The 1945 Battle for Iwo Jima

- ↑ Bartley, Whitman S. (1954), Chapter II: Plans and Preparations, High-Level Planning ,p. 39

- ↑ Bartley, p. 40

- ↑ Janis L. Edwards, and Carol K. Winkler, "Representative Form and the Visual Ideograph: the Iwo Jima Image in Editorial Cartoons." Quarterly Journal of Speech 1997 83(3): 289-310. Issn: 0033-5630