Photosynthesis: Difference between revisions

imported>Anthony.Sebastian (→Overview: attribute figure adaptation) |

imported>Anthony.Sebastian m (→Overview) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

{|align="left" cellpadding="5'" style="background:#ffcc99; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:10px; font-size: 85%; font-family: Gill Sans MT;" | {|align="left" cellpadding="5'" style="background:#ffcc99; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:10px; font-size: 85%; font-family: Gill Sans MT;" | ||

| | | | ||

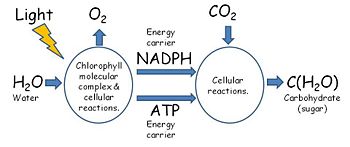

<b>Figure legend:</b> Photosynthesis divides into two components, an ''energy transduction'' component, shown on the left-hand side of the figure, and a ''carbon assimilation'' component, shown on the right-hand side of the figure. The former comprises the ''light-dependent'' reactions, the latter, the ''light-independent'' reactions. The carbon assimilation component converts [[Oxidation|oxidized]] carbon dioxide (CO<sub>2</sub>) into energy-rich [[Oxidation|reduced]] carbon compounds, such as carbohydrates, that have had electrons donated to them in order to build carbon-carbon bonds and other covalent carbon bonds. The ATP produced in the energy transduction process supplies energy for carbon assimilation, and the NADPH — the 'reducing' power — supplies the electrons. Thus, both [[ATP]] and [[NADPH]] serve as carriers of the energy harvested from the sun, the special role of NADPH as electron donor for the reduction of carbon dioxide to carbohydrate. (Figure adapted from Hopkins (2006)). | <b>Figure legend:</b> Photosynthesis divides into two components, an ''energy transduction'' component, shown on the left-hand side of the figure, and a ''carbon assimilation'' component, shown on the right-hand side of the figure. The former comprises the ''light-dependent'' reactions, the latter, the ''light-independent'' reactions. The carbon assimilation component converts [[Oxidation|oxidized]] carbon dioxide (CO<sub>2</sub>) into energy-rich [[Oxidation|reduced]] carbon compounds, such as carbohydrates, that have had electrons donated to them in order to build carbon-carbon bonds and other covalent carbon bonds. The ATP produced in the energy transduction process supplies energy for carbon assimilation, and the NADPH — the 'reducing' power — supplies the electrons. Thus, both [[ATP]] and [[NADPH]] serve as carriers of the energy harvested from the sun, the special role of NADPH as electron donor for the reduction of carbon dioxide to carbohydrate. (Figure adapted from Hopkins (2006)<ref name=hopkins2006>Hopkins WG. (2006) ''Photosynthesis and Respiration''. Chelsea House. ISBN 978-0-7910-8561-5.</ref>). | ||

|} | |} | ||

{{col-end}} | {{col-end}} | ||

Revision as of 17:38, 26 June 2010

In the light-initiated and light-driven physico-chemical process of photosynthesis, an activity performed by certain types of living systems, an organism synthesizes its own constituent, energy-rich organic compounds from inorganic starting materials using sunlight as the ultimate energy source to enable the metabolic work required to implement the synthetic process. Most but not all photosynthesis-capable organisms generate not only their own constituent organic compounds but also generate the oxygen required to release the energy from those compounds that enables the work of living, with enough oxygen leftover to replenish the oxygen in the atmosphere consumed by non-photosynthesis-capable organisms. At the same time they contribute to removing carbon dioxide discharged into the atmosphere by those non-photosynthesis capable organisms, carbon dioxide serving as the inorganic carbon source for the light-energy-driven synthesis of organic carbon compounds.[1] [2]

Metaphorically, the photosynthesis-capable organism sustains its living state by harvesting and eating the sun,[3] qualifying it as a so-called autotroph, specifically a photoautotroph,[4] eating a diet solely of inorganic compounds using solar energy — the 'inorg-an' equivalent of a 'veg-an'. In so doing it serves as a source of energy-rich organic compounds, as food, for Earth's non-photosynthesis-capable organisms, referred to as heterotrophs.

The term 'photosynthesis' derives from Greek roots for 'light' and 'putting together' or 'assembling', referring to sunlight energy utilized to assemble organic compounds.

Our current scientific understanding considers the oxygen-generating-carbon-dioxide consuming-type of photosynthesis our biosphere's most important bio-physico-chemical process, necessary for maintaining biosphere vitality by modulating the composition of the atmosphere and providing a food source for non-photosynthesis-capable organisms, among other services it offers the biosphere.[5] A photosynthesis-capable organism resides in a downhill energy gradient — a downhill flow of energetic solar photons — harvesting some of it to perform the work of living, reducing its internal entropy through self-organization, remaining for a lifetime far from the equilibrium state wherein the organism becomes lifeless. Its natural lifespan may never actualize, as it enters the food chain of the non-photosynthesis-capable organisms abundant in the biosphere.

In sum, a photosynthesis-capable organism captures a portion of the energy of sunlight, converting (transducing) it to, and storing it as, chemical energy (in the form of energy-rich organic compounds), which the organism uses in its cellular processes for growth, maintenance, and reproduction, thereby obviating any need for the organism, a so-called autotroph, to feed on other organisms for organic matter to meet its substrate and energy needs.[1] [2] A large number and variety of organisms (e.g., plants, algae and certain bacteria — so-called phototrophic bacteria) carry out a type of photosynthesis, and in so constructing themselves from inorganic chemicals supply the source of food for the rest of the living world. An estimated half the genera of organisms alive 65 million years ago purportedly perished due to a temporary shutting down of photosynthesis caused by a global blocking of sunlight reaching Earth's surface due to a dense atmospheric dust produced by an asteroid impacting the planet — indicating the fundamental importance of photosynthetic organisms in sustaining the living world.[6] (See also Blankenship (2002), Chapter 1, page 1[2])

Overview

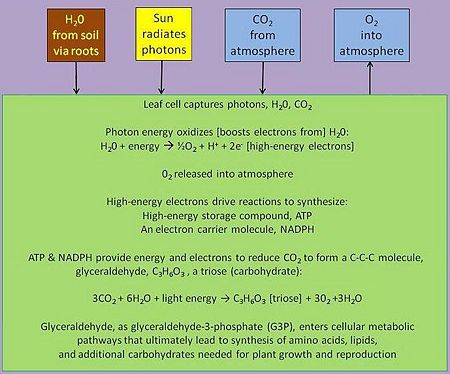

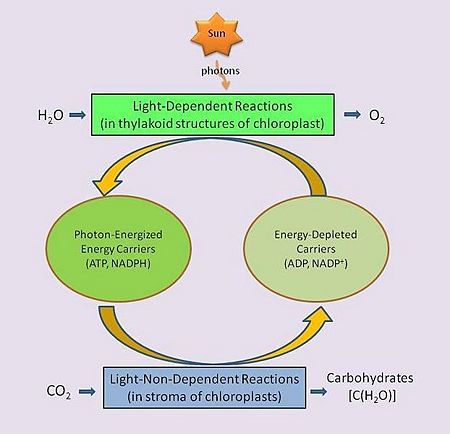

In the familiar example of green plants, but also in phototropic algae and bacteria, the photosynthetic process utilizes special photon-absorbing pigment molecules, called chlorophylls, to enable the energy of photons radiated from the sun to energize electrons in those molecules, electrons ultimately supplied by the splitting of water molecules in a reaction that also converts water's oxygen atoms to molecular oxygen for release into the atmosphere and for use by the plant. The energized electrons subsequently transfer their energy in chemical reactions to energy-carrier molecules — generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) [see figure below], the energy therein used to synthesize organic compounds using the inorganic carbon compound, carbon dioxide, as the carbon source starting material. Besides water and carbon dioxide, the photosynthesizing organism also draws from the environment other inorganic material (e.g., phosphorus, nitrogen, sulfur) needed to synthesize organic compounds.

|

The major starting and replenishing materials — water (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2) — abound in the environment, H2O providing the electrons for the initial photon-driven electron energizing mechanisms, releasing the H2O´s oxygen into the environment, CO2 providing the carbon source for the energy-storing reduction mechanisms (addition of electrons) that generate the organic molecules. The photosynthesizing organisms, and the non-photosynthesizing organisms that feed on them, ultimately use those energy-rich organic molecules as cellular building blocks and energy sources, enabling the cellular structures and functions that maintain the activities of living for nearly every living system on Earth.[8] Living systems on Earth, with notable exceptions, are "solar powered".

The origin and evolution of photosynthesis rank as major steps in the evolution of living systems, pumping oxygen into the atmosphere, absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and for organisms that cannot generate their own food, serving as a source of chemical energy and organic matter. In the absence of photosynthesis, nearly all life on earth as we know it would perish.

Without photosynthesis the luxuriant, awe-inspiring variety of living systems we see in the terrestrial and marine world about us would not exist. Nearly all living systems on Earth depend directly or indirectly on the energy captured by photosynthesis from light energy radiating to our planet from our sun (see below). For us humans photosynthesis indirectly provides essentially all of our food-energy, as well the bulk of our non-food energy resources, inasmuch as ancient photosynthesizing organisms produced the energy-rich carbon-containing molecules we combust as fossil fuels — oil, natural gas, coal and wood — to generate electricity and other forms of energy we use to support human activity.

Nearly every oxygen atom that we inhale from the atmosphere emerged through photosynthetic liberation from a water molecule, among the countless water molecules covering 70% of the Earth´s surface. The chemical energy our bodies generate using that oxygen in biochemically combusting our food represents, almost literally, the energy that photosynthesis secured from the energy in sunlight.[9] Likewise, the energy we generate with that oxygen in combusting fuels — oil, coal, wood, natural gas — owes its origin to photosynthetic capture of the energy of sunlight. The sun offers the energy of life, and the living process of photosynthesis accepts the offer and distributes it.

Aims of article

This article will classify the differing types of photosynthesizing organisms, and describe the details of the differing photosynthetic mechanisms employed by them. It focuses on those photosynthetic organisms and processes that employ chlorophyll molecules for photon absorption, but will briefly discuss a different form of photosynthesis by certain bacteria using a rhodopsin-type molecule, and consider organisms that derive only a part of their energy from light. It will also discuss the implications of photosynthesis in the sciences of biology, geology, oceanography, climatology, and other areas of importance to the life of planet Earth, since without photosynthesis nearly every species on Earth would perish.[8][2][10][11][12][13][14] [3]

Chlorophyll-based photosynthesis

Photosynthesis based on chlorophyll-type pigment molecules is the most common type of photosynthesis, using photon-driven energizing and transferring of electrons. Chlorophyll-based photosynthesis is carried out by plants, algae, cyanobacteria, and certain organisms that differ in virtue of not generating oxygen during the process. A simplified overview of chlorophyll-based oxygen-generating photosynthesis is shown in the accompanying illustration.

In green plants, the biological process of photosynthesis typically occurs in leaf cells but also in all green parts of the plant (.e.g., the stems). They capture the energy from photons in sunlight, use it to energize electrons split from water and release a largely 'waste' product, oxygen (O2) — thus defining 'oxygenic' photosynthesis. The captured and transformed energy is then used to drive a set of biochemical reactions that converts carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) to a carbohydrate compound, a triose, a 3-carbon sugar.[15].

Triose, as triose phosphates, exit the leaf cell's organelles that synthesizes them — viz., a chloroplast, condense themselves into six-carbon hexose phosphates, ultimately forming dimers like sucrose, or polymers like starch or cellulose, the so-called reduced forms of carbon. Thus, the mass of plants, and their predators in the food chain, is from the enrichment of water's electrons energized by captured photons and the subsequent formation of energy-rich carbon compounds from the carbon dioxide in the air.

Between these two steps, a variety of energy-rich intermediates are formed, some of which can be metabolized by the photosynthetic organism. Light reactions can generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a recirculating and recyclable energy currency of cells. The process also produces other recyclable forms of circulating energy currency (e.g., NADPH). Photosynthesizing cells thus convert light energy to the life-sustaining chemical energy that drives life-sustaining cellular processes.

Organisms that photosynthesize operate as autotrophs — viz., organisms that generate their own source of food-energy — specifically referred to as photoautotrophs. They draw on minerals and other inorganic compounds from the environment and produce an ultimately photon-energy-derived complement of carbohydrates, proteins, lipids and nucleic acids that self-organize the photoautotophic organism. In doing so they directly, though blindly, offer themselves as a source of food-energy (e.g., as vegetables, fruits) for consumption by us humans and other organisms, so-called heterotrophs — viz., organisms that feed on other organisms or on their energy-rich structural components — and indirectly provide a source of food-energy in the form of the non-human heterotrophs that we humans consume (e.g., chicken, fish and other animals). Photosynthesizing cells also supply the sufficient amounts of oxygen they and we need to generate ATP and NADPH, and they consume the 'waste' CO2 produced in the process of generating ATP.

Not all photosynthesizing organisms produce oxygen. The specific physico-chemical reactions of those that do biologists refer to as oxygenic photosynthesis, and those that do not as 'anoxygenic' photosynthesis. As noted above, oxygenic photosynthesis accounts for nearly all of the oxygen in the atmosphere.

Solar energy

Photosynthesizing organisms do not eat all of the photons available to them....

References Cited and Notes in Text

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hall DO, Rao KK. (1999) Photosynthesis. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64257-4. | Google Books preview.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Blankenship RE (2002) Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0632043210; ISBN 978-0632043217

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 O. Morton (2008) Eating the Sun: How Plants Power the Planet. Harper Collins. ISBN 0007163649 , ISBN 978-0007163649

- ↑ phototroph: ‘an organism that obtains energy from light’. Beatty JT. (2002) On the natural selection and evolution of the aerobic phototrophic bacteria. Photosynthesis Research 73:109-114. | For the quote, Beatty cites: Madigan MT, Martinko JM and Parker J (2000) Brock Biology of Microorganisms. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

- ↑ Some ocean bottom organisms can utilize energy released by radioactive chemical elements, originating deep below the ocean bottom, to assemble their organic constituents, so a fringe of the biosphere might remain vital in the absence of sunlight.

- ↑ Alvarez LW, Alvarez W, Asaro F, Michel HV. (1980) Extraterrestrial Cause for the Cretaceous-Tertiary Extinction. Science 208:1095-1108.

- ↑ Hopkins WG. (2006) Photosynthesis and Respiration. Chelsea House. ISBN 978-0-7910-8561-5.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 W. Vermass (2007) An Introduction to Photosynthesis and Its Applications.

- ↑ H.M. Weiss (2008), Appreciating Oxygen. The Journal of Chemical Education 85(9):1218-1219. This article stresses the importance of oxygen as an energy source in chemistry and bioligy.

- ↑ M.J. Farabee (2007), What is photosynthesis? Online Biology Book Detailed teatment of photosynthesis in an online biology course textbook. Includes an illustrated glossary.

- ↑ Photosynthesis Encyclopedia Britannica, Free Full-Text Article

- ↑ John Whitmarsh, Govindjee. The Photosynthetic Process In: Concepts in Photobiology: Photosynthesis and Photomorphogenesis, Edited by G.S. Singhal, G. Renger, S.K. Sopory, K-D Irrgang and Govindjee, Narosa Publishers/New Delhi; and Kluwer Academic/Dordrecht, pp. 11-51. The online text is a revised and modified version of Photosynthesis by J. Whitmarsh and Govindjee (1995), published in Encyclopedia of Applied Physics (Vol. 13, pp. 513-532) by VCH Publishers, Inc. A detailed, comprehensive treatment of photosynthesis in a book chapter online. Includes history and research aspects.

- ↑ P.H. Raven, R.F. Evert and S.E. Eichhorn (1999), Photosynthesis, Light, and Life'. Chapter 7. In: Biology of Plants, 6th ed., New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 1-57259-041-6; ISBN 1-57259-611-2

- ↑ N.C. Kiang, J. Siefert, Govindjee and R.E. Blankenship (2007). Full text available at Spectral Signatures of Photosynthesis. I. Review of Earth Organisms An overview of: how photosynthesis works, the diversity of photosynthetic organisms, a synthesis of photosynthetic surface spectral signatures, and evolutionary rationales for photosynthetic surface reflectance spectra.

- ↑ Note: Summary equations typically depict glucose as the carbohydrate end-product of photosynthesis, whereas photosynthesizing cells generate very little glucose per se; the three-carbon trioses represent the more immediate photosynthetic carbohydrate.