User:John R. Brews/Sample2: Difference between revisions

imported>John R. Brews No edit summary |

imported>John R. Brews No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{TOC|right}} | {{TOC|right}} | ||

[[Image:Block Diagram for Feedback.svg|thumb|Figure 1: Ideal negative feedback model|300px|right]] | |||

== | A '''negative feedback amplifier''' (or more commonly simply a '''feedback amplifier''') is an amplifier a fraction of the output of which is combined with the input so that a [[negative feedback]] opposes the original signal. The applied negative feedback improves performance (gain stability, linearity, frequency response, [[step response]]) and reduces sensitivity to parameter variations due to manufacturing or environment. Because of these advantages, negative feedback is used in this way in many amplifiers and control systems.<ref name=Kuo>{{cite book | ||

|author=Kuo, Benjamin C & Farid Golnaraghi | |||

|title=Automatic control systems | |||

|edition=Eighth edition | |||

|page=46 | |||

|year= 2003 | |||

|publisher=Wiley | |||

|location=NY | |||

|isbn=0471134767 | |||

|url=http://worldcat.org/isbn/0471134767}} | |||

</ref> | |||

A negative feedback amplifier is a system of three elements (see Figure 1): an ''amplifier'' with gain ''A''<sub>OL</sub>, an attenuating ''feedback network'' with a constant β < 1 and a summing circuit acting as a ''subtractor'' (the circle in the figure). The amplifier is the only obligatory; the other elements may be omitted in some cases. For example, in a voltage ([[Emitter follower|emitter]], [[Common drain|source]], [[Operational amplifier applications#Voltage follower|op-amp]]) follower the feedback network and the summing circuit are not necessary. | |||

== Overview == | |||

Fundamentally, all electronic devices used to provide power gain (e.g. [[vacuum tube]]s, [[BJT|bipolar transistors]], [[FET|MOS transistors]]) are [[nonlinear]]. Negative feedback allows [[gain]] to be traded for higher linearity (reducing [[distortion]]), amongst other things. If not designed correctly amplifiers with negative feedback can become unstable, resulting in unwanted behavior, such as [[oscillation]]. The [[Nyquist stability criterion]] developed by [[Harry Nyquist]] of [[Bell Laboratories]] can be used to study the stability of feedback amplifiers. | |||

Feedback amplifiers share these properties:<ref name=Palumbo> | |||

{{cite book | |||

|author=Palumbo, Gaetano & Salvatore Pennisi | |||

|title=Feedback amplifiers: theory and design | |||

|page=64 | |||

|year= 2002 | |||

|publisher=Kluwer Academic | |||

|location=Boston/Dordrecht/London | |||

|isbn=0792376439 | |||

|url=http://worldcat.org/isbn/0792376439}} | |||

</ref> | |||

Pros: | |||

*Can increase or decrease input [[Electrical impedance|impedance]] (depending on type of feedback) | |||

*Can increase or decrease output impedance (depending on type of feedback) | |||

*Reduces distortion (increases linearity) | |||

*Increases the bandwidth | |||

*Desensitizes gain to component variations | |||

*Can control [[step response]] of amplifier | |||

Cons: | |||

*May lead to instability if not designed carefully | |||

*The gain of the amplifier decreases | |||

*The input and output impedances of the amplifier with feedback (the '''closed-loop amplifier''') become sensitive to the gain of the amplifier without feedback (the '''open-loop amplifier'''); that exposes these impedances to variations in the open loop gain, for example, due to parameter variations or due to nonlinearity of the open-loop gain | |||

The | ==History== | ||

The negative feedback amplifier was invented by [[Harold Stephen Black]] (US patent 2,102,671 (issued in 1937)<ref>{{cite web | title=.| url=http://eepatents.com/patents/2102671.pdf | accessdate = 2005-10-24}} {{Dead link|date=October 2010|bot=H3llBot}}</ref> ) while a passenger on the Lackawanna Ferry (from Hoboken Terminal to Manhattan) on his way to work at [[Bell Laboratories]] (historically located in Manhattan instead of New Jersey in 1927) on August 2, 1927. Black had been toiling at reducing [[distortion]] in [[repeater]] amplifiers used for telephone transmission. On a blank space in his copy of The New York Times,<ref>Currently on display at Bell Laboratories in Mountainside, New Jersey</ref> he recorded the diagram found in Figure 1, and the equations derived below.<ref name=Waldhauer> | |||

{{cite book | |||

|author=Waldhauer, Fred | |||

|title=Feedback | |||

|page=3 | |||

|year= 1982 | |||

|publisher=Wiley | |||

|location=NY | |||

|isbn=0471053198 | |||

|url=http://worldcat.org/isbn/0471053198}} | |||

</ref> | |||

Black submitted his invention to the U. S. Patent Office on August 8, 1928, and it took more than nine years for the patent to be issued. Black later wrote: "One reason for the delay was that the concept was so contrary to established beliefs that the Patent Office initially did not believe it would work."<ref name=Black> | |||

{{cite news | |||

|author=Black, Harold | |||

|title=Inventing the negative feedback amplifier | |||

|date= Dec. 1977 | |||

|publisher=IEEE Spectrum}} | |||

</ref> | |||

==Classical feedback== | |||

=== Gain reduction === | |||

Below, the voltage gain of the amplifier with feedback, the '''closed-loop gain''' ''A''<sub>fb</sub>, is derived in terms of the gain of the amplifier without feedback, the '''open-loop gain''' ''A''<sub>OL</sub> and the '''feedback factor''' β, which governs how much of the output signal is applied to the input. See Figure 1, top right. The open-loop gain ''A''<sub>OL</sub> in general may be a function of both frequency and voltage; the feedback parameter β is determined by the feedback network that is connected around the amplifier. For an [[operational amplifier]] two resistors forming a voltage divider may be used for the feedback network to set β between 0 and 1. This network may be modified using reactive elements like [[capacitor]]s or [[inductor]]s to (a) give frequency-dependent closed-loop gain as in equalization/tone-control circuits or (b) construct oscillators. The gain of the amplifier with feedback is derived below in the case of a voltage amplifier with voltage feedback. | |||

Without feedback, the input voltage ''V'<sub>in</sub>'' is applied directly to the amplifier input. The according output voltage is | |||

:<math>V_{out} = A_{OL}\cdot V'_{in}</math> | |||

Suppose now that an attenuating feedback loop applies a fraction β.''V<sub>out</sub>'' of the output to one of the subtractor inputs so that it subtracts from the circuit input voltage ''V<sub>in</sub>'' applied to the other subtractor input. The result of subtraction applied to the amplifier input is | |||

</math> | :<math>V'_{in} = V_{in} - \beta \cdot V_{out}</math> | ||

Substituting for ''V'<sub>in</sub>'' in the first expression, | |||

:<math>V_{out} = A_{OL} (V_{in} - \beta \cdot V_{out})</math> | |||

Rearranging | |||

:<math>V_{out} (1 + \beta \cdot A_{OL}) = V_{in} \cdot A_{OL}</math> | |||

Then the gain of the amplifier with feedback, called the closed-loop gain, ''A<sub>fb</sub>'' is given by, | |||

:<math>A_\mathrm{fb} = \frac{V_\mathrm{out}}{V_\mathrm{in}} = \frac{A_{OL}}{1 + \beta \cdot A_{OL}}</math> | |||

If ''A''<sub>OL</sub> >> 1, then ''A''<sub>fb</sub> ≈ 1 / β and the effective amplification (or closed-loop gain) ''A''<sub>fb</sub> is set by the feedback constant β, and hence set by the feedback network, usually a simple reproducible network, thus making linearizing and stabilizing the amplification characteristics straightforward. Note also that if there are conditions where β ''A''<sub>OL</sub> = −1, the amplifier has infinite amplification – it has become an oscillator, and the system is unstable. The stability characteristics of the gain feedback product β ''A''<sub>OL</sub> are often displayed and investigated on a [[Nyquist plot]] (a polar plot of the gain/phase shift as a parametric function of frequency). A simpler, but less general technique, uses [[Bode plot#Gain margin and phase margin|Bode plot]]s. | |||

The combination ''L'' = β ''A''<sub>OL</sub> appears commonly in feedback analysis and is called the '''loop gain'''. The combination ( 1 + β ''A''<sub>OL</sub> ) also appears commonly and is variously named as the '''desensitivity factor''' or the '''improvement factor'''. | |||

::< | ===Bandwidth extension=== | ||

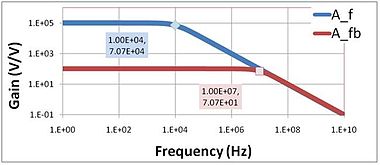

[[Image:Bandwidth comparison.JPG|thumb|380px|Figure 2: Gain vs. frequency for a single-pole amplifier with and without feedback; corner frequencies are labeled.]] | |||

Feedback can be used to extend the bandwidth of an amplifier (speed it up) at the cost of lowering the amplifier gain.<ref>[http://bwrc.eecs.berkeley.edu/classes/ee140/Lectures/10_stability.pdf RW Brodersen ''Analog circuit design: lectures on stability'' ]</ref> Figure 2 shows such a comparison. The figure is understood as follows. Without feedback the so-called '''open-loop''' gain in this example has a single time constant frequency response given by | |||

::<math> A_{OL}(f) = \frac {A_0} { 1+ j f / f_C } \ , </math> | |||

</math> | |||

: | where ''f<sub>C</sub>'' is the [[cutoff frequency|cutoff]] or [[corner frequency]] of the amplifier: in this example ''f<sub>C</sub>'' = 10<sup>4</sup> Hz and the gain at zero frequency A<sub>0</sub> = 10<sup>5</sup> V/V. The figure shows the gain is flat out to the corner frequency and then drops. When feedback is present the so-called '''closed-loop''' gain, as shown in the formula of the previous section, becomes, | ||

::<math> A_{fb} (f) = \frac { A_{OL} } { 1 + \beta A_{OL} } </math> | |||

::<math> | ::::<math> = \frac { A_0/(1+jf/f_C) } { 1 + \beta A_0/(1+jf/f_C) } </math> | ||

\ | ::::<math> = \frac {A_0} {1+ jf/f_C + \beta A_0} </math> | ||

::::<math> = \frac {A_0} {(1 + \beta A_0) \left(1+j \frac {f} {(1+ \beta A_0) f_C } \right)} | |||

\ . | |||

</math> | </math> | ||

( | The last expression shows the feedback amplifier still has a single time constant behavior, but the corner frequency is now increased by the improvement factor ( 1 + β A<sub>0</sub> ), and the gain at zero frequency has dropped by exactly the same factor. This behavior is called the '''[[gain-bandwidth product|gain-bandwidth tradeoff]]'''. In Figure 2, ( 1 + β A<sub>0</sub> ) = 10<sup>3</sup>, so ''A<sub>fb</sub>''(0)= 10<sup>5</sup> / 10<sup>3</sup> = 100 V/V, and ''f<sub>C</sub>'' increases to 10<sup>4</sup> × 10<sup>3</sup> = 10<sup>7</sup> Hz. | ||

===Multiple poles=== | |||

When the open-loop gain has several poles, rather than the single pole of the above example, feedback can result in complex poles (real and imaginary parts). In a two-pole case, the result is peaking in the frequency response of the feedback amplifier near its corner frequency, and [[ringing artifacts|ringing]] and [[overshoot (signal)|overshoot]] in its [[step response]]. In the case of more than two poles, the feedback amplifier can become unstable, and oscillate. See the discussion of [[Bode plot#Gain margin and phase margin|gain margin and phase margin]]. For a complete discussion, see Sansen.<ref name=Sansen> | |||

{{cite book | |||

|author=Willy M. C. Sansen | |||

|title=Analog design essentials | |||

|year= 2006 | |||

|pages=§0513-§0533, p. 155–165 | |||

|publisher=Springer | |||

|location=New York; Berlin | |||

|isbn=0-387-25746-2 | |||

|url=http://worldcat.org/isbn/0-387-25746-2}} | |||

</ref> | |||

==Asymptotic gain model== | |||

{{main|asymptotic gain model}} | |||

In the above analysis the feedback network is [[Electronic amplifier#Unilateral or bilateral|unilateral]]. However, real feedback networks often exhibit '''feed forward''' as well, that is, they feed a small portion of the input to the output, degrading performance of the feedback amplifier. A more general way to model negative feedback amplifiers including this effect is with the [[asymptotic gain model]]. | |||

==Feedback and amplifier type== | |||

Amplifiers use current or voltage as input and output, so four types of amplifier are possible. See [[Electronic amplifier#Input and output variables|classification of amplifiers]]. Any of these four choices may be the open-loop amplifier used to construct the feedback amplifier. The objective for the feedback amplifier also may be any one of the four types of amplifier, not necessarily the same type as the open-loop amplifier. For example, an op amp (voltage amplifier) can be arranged to make a current amplifier instead. The conversion from one type to another is implemented using different feedback connections, usually referred to as series or shunt (parallel) connections.<ref>[http://www.ece.mtu.edu/faculty/goel/EE-4232/Feedback.pdf Ashok K. Goel ''Feedback topologies'']</ref><ref>[http://centrevirtuel.creea.u-bordeaux.fr/ELAB/docs/freebooks.php/virtual/feedback-amplifier/textbook_feedback.html#1.2 Zimmer T & Geoffreoy D: ''Feedback amplifier'']</ref> See the table below. | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="background:white;text-align:center " | |||

!Feedback amplifier type | |||

!Input connection | |||

!Output connection | |||

!Ideal feedback | |||

!Two-port feedback | |||

|- | |||

|-valign="top" | |||

| '''Current''' | |||

| '''Shunt''' | |||

| '''Series''' | |||

| '''CCCS''' | |||

| '''g-parameter''' | |||

|- | |||

|-valign="top" | |||

| '''Transresistance''' | |||

| '''Shunt''' | |||

| '''Shunt''' | |||

| '''CCVS''' | |||

| '''y-parameter''' | |||

|- | |||

|-valign="top" | |||

| '''Transconductance''' | |||

| '''Series''' | |||

| '''Series | |||

| '''VCCS''' | |||

| '''z-parameter''' | |||

|- | |||

|-valign="top" | |||

| '''Voltage''' | |||

| '''Series''' | |||

| '''Shunt''' | |||

| '''VCVS''' | |||

| '''h-parameter''' | |||

|} | |||

The feedback can be implemented using a [[two-port network]]. There are four types of two-port network, and the selection depends upon the type of feedback. For example, for a current feedback amplifier, current at the output is sampled and combined with current at the input. Therefore, the feedback ideally is performed using an (output) current-controlled current source (CCCS), and its imperfect realization using a two-port network also must incorporate a CCCS, that is, the appropriate choice for feedback network is a g-parameter two-port. | |||

==Two-port analysis of feedback== | |||

One approach to feedback is the use of [[return ratio]]. Here an alternative method used in most textbooks<ref>[http://organics.eecs.berkeley.edu/~viveks/ee140/lectures/section10p4.pdf Vivek Subramanian: ''Lectures on feedback'' ]</ref><ref name=Gray-Meyer1> | |||

{{cite book | |||

|author=P R Gray, P J Hurst, S H Lewis, and R G Meyer | |||

|title=Analysis and Design of Analog Integrated Circuits | |||

|year= 2001 | |||

|pages=586–587 | |||

|edition=Fourth Edition | |||

|publisher=Wiley | |||

|location=New York | |||

|isbn=0-471-32168-0 | |||

|url=http://worldcat.org/isbn/0471321680}}</ref><ref name=Sedra1> | |||

{{cite book | |||

|author=A. S. Sedra and K.C. Smith | |||

|title=Microelectronic Circuits | |||

|year= 2004 | |||

|edition=Fifth Edition | |||

|pages=Example 8.4, pp. 825–829 and PSpice simulation pp. 855–859 | |||

|publisher=Oxford | |||

|location=New York | |||

|isbn=0-19-514251-9 | |||

|url=http://worldcat.org/isbn/0-19-514251-9 | |||

|nopp=true}} | |||

</ref> is presented by means of an example treated in the article on [[Asymptotic gain model#Two-stage transistor amplifier|asymptotic gain model]]. | |||

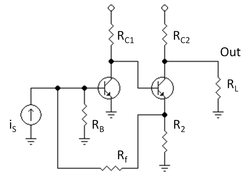

[[Image:Two-transistor feedback amp.PNG|thumbnail|250px|Figure 3: A ''shunt-series'' feedback amplifier]] | |||

Figure 3 shows a two-transistor amplifier with a feedback resistor ''R<sub>f</sub>''. The aim is to analyze this circuit to find three items: the gain, the output impedance looking into the amplifier from the load, and the input impedance looking into the amplifier from the source. | |||

===Replacement of the feedback network with a two-port=== | |||

The first step is replacement of the feedback network by a [[two-port network|two-port]]. Just what components go into the two-port? | |||

On the input side of the two-port we have ''R<sub>f</sub>''. If the voltage at the right side of ''R<sub>f</sub>'' changes, it changes the current in ''R<sub>f</sub>'' that is subtracted from the current entering the base of the input transistor. That is, the input side of the two-port is a dependent current source controlled by the voltage at the top of resistor ''R<sub>2</sub>''. | |||

One might say the second stage of the amplifier is just a [[voltage follower]], transmitting the voltage at the collector of the input transistor to the top of ''R<sub>2</sub>''. That is, the monitored output signal is really the voltage at the collector of the input transistor. That view is legitimate, but then the voltage follower stage becomes part of the feedback network. That makes analysis of feedback more complicated. | |||

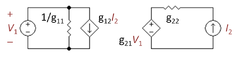

[[Image:G-equivalent circuit.PNG|thumbnail|250px|Figure 4: The g-parameter feedback network]] | |||

An alternative view is that the voltage at the top of ''R<sub>2</sub>'' is set by the emitter current of the output transistor. That view leads to an entirely passive feedback network made up of ''R<sub>2</sub>'' and ''R<sub>f</sub>''. The variable controlling the feedback is the emitter current, so the feedback is a current-controlled current source (CCCS). We search through the four available [[two-port network]]s and find the only one with a CCCS is the g-parameter two-port, shown in Figure 4. The next task is to select the g-parameters so that the two-port of Figure 4 is electrically equivalent to the L-section made up of ''R<sub>2</sub>'' and ''R<sub>f</sub>''. That selection is an algebraic procedure made most simply by looking at two individual cases: the case with ''V<sub>1</sub>'' = 0, which makes the VCVS on the right side of the two-port a short-circuit; and the case with ''I<sub>2</sub>'' = 0. which makes the CCCS on the left side an open circuit. The algebra in these two cases is simple, much easier than solving for all variables at once. The choice of g-parameters that make the two-port and the L-section behave the same way are shown in the table below. | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="background:white;text-align:center " | |||

!g<sub>11</sub> | |||

!g<sub>12</sub> | |||

!g<sub>21</sub> | |||

!g<sub>22</sub> | |||

|- | |||

|-valign="center" | |||

| '''<math>\frac {1} {R_f+R_2}</math>''' | |||

| '''<math> - \frac {R_2}{R_2+R_f}</math>'' | |||

| '''<math> \frac {R_2} {R_2+R_f} </math>''' | |||

| '''<math>R_2//R_f \ </math>''' | |||

|} | |||

[[Image:Small-signal current amplifier with feedback.PNG|thumbnail|400px|Figure 5: Small-signal circuit with two-port for feedback network; upper shaded box: main amplifier; lower shaded box: feedback two-port replacing the ''L''-section made up of ''R''<sub>f</sub> and ''R''<sub>2</sub>.]] | |||

===Small-signal circuit=== | |||

The next step is to draw the small-signal schematic for the amplifier with the two-port in place using the [[hybrid-pi model]] for the transistors. Figure 5 shows the schematic with notation ''R<sub>3</sub>'' = ''R<sub>C2</sub> // R<sub>L</sub>'' and ''R<sub>11</sub>'' = 1 / ''g<sub>11</sub>'', ''R<sub>22</sub>'' = ''g<sub>22</sub>'' . | |||

===Loaded open-loop gain=== | |||

Figure 3 indicates the output node, but not the choice of output variable. A useful choice is the short-circuit current output of the amplifier (leading to the short-circuit current gain). Because this variable leads simply to any of the other choices (for example, load voltage or load current), the short-circuit current gain is found below. | |||

First the loaded '''open-loop gain''' is found. The feedback is turned off by setting ''g<sub>12</sub> = g<sub>21</sub>'' = 0. The idea is to find how much the amplifier gain is changed because of the resistors in the feedback network by themselves, with the feedback turned off. This calculation is pretty easy because ''R<sub>11</sub>, R<sub>B</sub>, and r<sub>π1</sub>'' all are in parallel and ''v<sub>1</sub> = v<sub>π</sub>''. Let ''R<sub>1</sub>'' = ''R<sub>11</sub> // R<sub>B</sub> // r<sub>π1</sub>''. In addition, ''i<sub>2</sub> = −(β+1) i<sub>B</sub>''. The result for the open-loop current gain ''A<sub>OL</sub>'' is: | |||

::<math> A_{OL} = \frac { \beta i_B } {i_S} = g_m R_C \left( \frac { \beta }{ \beta +1} \right) | |||

\left( | |||

\frac {R_1} {R_{22} + | |||

\frac {r_{ \pi 2} + R_C } {\beta + 1 } } \right) \ . </math> | |||

===Gain with feedback=== | |||

In the classical approach to feedback, the feedforward represented by the VCVS (that is, ''g<sub>21</sub> v<sub>1</sub>'') is neglected.<ref>If the feedforward is included, its effect is to cause a modification of the open-loop gain, normally so small compared to the open-loop gain itself that it can be dropped. Notice also that the main amplifier block is [[Electronic amplifier#Unilateral or bilateral|unilateral]].</ref> That makes the circuit of Figure 5 resemble the block diagram of Figure 1, and the gain with feedback is then: | |||

::<math> | ::<math> A_{FB} = \frac { A_{OL} } {1 + { \beta }_{FB} A_{OL} } </math> | ||

:::<math> = \frac {A_{OL} } {1 + \frac {R_2} {R_2+R_f} A_{OL} } \ , </math> | |||

where the feedback factor β<sub>FB</sub> = −g<sub>12</sub>. Notation β<sub>FB</sub> is introduced for the feedback factor to distinguish it from the transistor β. | |||

:: | ===Input and output resistances=== | ||

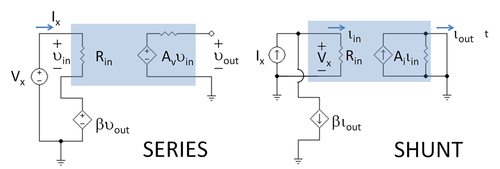

[[Image:Feedback amplifier input resistance.PNG|thumb|500px|Figure 6: Circuit set-up for finding feedback amplifier input resistance]] | |||

First, a digression on how two-port theory approaches resistance determination, and then its application to the amplifier at hand. | |||

and | ====Background on resistance determination==== | ||

Figure 6 shows an equivalent circuit for finding the input resistance of a feedback voltage amplifier (left) and for a feedback current amplifier (right). These arrangements are typical [[Miller theorem#Applications|Miller theorem applications]]. | |||

In | In the case of the voltage amplifier, the output voltage β''V<sub>out</sub>'' of the feedback network is applied in series and with an opposite polarity to the input voltage ''V<sub>x</sub>'' travelling over the loop (but in respect to ground, the polarities are the same). As a result, the effective voltage across and the current through the amplifier input resistance ''R''<sub>in</sub> decrease so that the circuit input resistance increases (one might say that ''R''<sub>in</sub> apparently increases). Its new value can be calculated by applying [[Miller theorem#Miller theorem (for voltages)|Miller theorem]] (for voltages) or the basic circuit laws. Thus [[Kirchhoff's circuit laws|Kirchhoff's voltage law]] provides: | ||

::<math> V_x = I_x R_{in} + \beta v_{out} \ , </math> | |||

{{ | |||

where ''v''<sub>out</sub> = ''A''<sub>v</sub> ''v''<sub>in</sub> = ''A''<sub>v</sub> ''I''<sub>x</sub> ''R''<sub>in</sub>. Substituting this result in the above equation and solving for the input resistance of the feedback amplifier, the result is: | |||

:: | ::<math> R_{in}(fb) = \frac {V_x} {I_x} = \left( 1 + \beta A_v \right ) R_{in} \ . </math> | ||

The general conclusion to be drawn from this example and a similar example for the output resistance case is: | |||

''A series feedback connection at the input (output) increases the input (output) resistance by a factor ( 1 + β ''A''<sub>OL</sub> )'', where ''A''<sub>OL</sub> = open loop gain. | |||

On the other hand, for the current amplifier, the output current β''I<sub>out</sub>'' of the feedback network is applied in parallel and with an opposite direction to the input current ''I<sub>x</sub>''. As a result, the total current flowing through the circuit input (not only through the input resistance ''R''<sub>in</sub>) increases and the voltage across it decreases so that the circuit input resistance decreases (''R''<sub>in</sub> apparently decreases). Its new value can be calculated by applying the [[Miller theorem#Dual Miller theorem (for currents)|dual Miller theorem]] (for currents) or the basic Kirchhoff's laws: | |||

{{ | ::<math> I_x = \frac {V_{in}} {R_{in}} + \beta i_{out} \ . </math> | ||

where ''i''<sub>out</sub> = ''A''<sub>i</sub> ''i''<sub>in</sub> = ''A''<sub>i</sub> ''V''<sub>x</sub> / ''R''<sub>in</sub>. Substituting this result in the above equation and solving for the input resistance of the feedback amplifier, the result is: | |||

::<math> \frac { | ::<math> R_{in}(fb) = \frac {V_x} {I_x} = \frac { R_{in} } { \left( 1 + \beta A_i \right ) } \ . </math> | ||

The general conclusion to be drawn from this example and a similar example for the output resistance case is: | |||

''A parallel feedback connection at the input (output) decreases the input (output) resistance by a factor ( 1 + β ''A''<sub>OL</sub> )'', where ''A''<sub>OL</sub> = open loop gain. | |||

These conclusions can be generalized to treat cases with arbitrary [[Norton's theorem|Norton]] or [[Thevenin's theorem|Thévenin]] drives, arbitrary loads, and general [[two-port network|two-port feedback networks]]. However, the results do depend upon the main amplifier having a representation as a two-port – that is, the results depend on the ''same'' current entering and leaving the input terminals, and likewise, the same current that leaves one output terminal must enter the other output terminal. | |||

A broader conclusion to be drawn, independent of the quantitative details, is that feedback can be used to increase or to decrease the input and output impedances. | |||

====Application to the example amplifier==== | |||

These resistance results now are applied to the amplifier of Figure 3 and Figure 5. The ''improvement factor'' that reduces the gain, namely ( 1 + β<sub>FB</sub> A<sub>OL</sub>), directly decides the effect of feedback upon the input and output resistances of the amplifier. In the case of a shunt connection, the input impedance is reduced by this factor; and in the case of series connection, the impedance is multiplied by this factor. However, the impedance that is modified by feedback is the impedance of the amplifier in Figure 5 with the feedback turned off, and does include the modifications to impedance caused by the resistors of the feedback network. | |||

Therefore, the input impedance seen by the source with feedback turned off is ''R''<sub>in</sub> = ''R''<sub>1</sub> = ''R''<sub>11</sub> // ''R''<sub>B</sub> // ''r''<sub>π1</sub>, and with the feedback turned on (but no feedforward) | |||

= | ::<math> R_{in} = \frac {R_1} {1 + { \beta }_{FB} A_{OL} } \ , </math> | ||

{{ | |||

< | where ''division'' is used because the input connection is ''shunt'': the feedback two-port is in parallel with the signal source at the input side of the amplifier. A reminder: ''A''<sub>OL</sub> is the ''loaded'' open loop gain [[Negative feedback amplifier#Loaded open-loop gain|found above]], as modified by the resistors of the feedback network. | ||

<ref name= | The impedance seen by the load needs further discussion. The load in Figure 5 is connected to the collector of the output transistor, and therefore is separated from the body of the amplifier by the infinite impedance of the output current source. Therefore, feedback has no effect on the output impedance, which remains simply ''R<sub>C2</sub>'' as seen by the load resistor ''R<sub>L</sub>'' in Figure 3.<ref>The use of the improvement factor ( 1 + β<sub>FB</sub> A<sub>OL</sub>) requires care, particularly for the case of output impedance using series feedback. See Jaeger, note below.</ref><ref name=Jaeger>{{cite book | title = Microelectronic Circuit Design | author =R.C. Jaeger and T.N. Blalock | publisher = McGraw-Hill Professional | year = 2006 |edition=Third Edition |page=Example 17.3 pp. 1092–1096| isbn = 978-0-07-319163-8 | url = http://worldcat.org/isbn/978-0-07-319163-8 | nopp = true }}</ref> | ||

<ref | If instead we wanted to find the impedance presented at the ''emitter'' of the output transistor (instead of its collector), which is series connected to the feedback network, feedback would increase this resistance by the improvement factor ( 1 + β<sub>FB</sub> A<sub>OL</sub>).<ref>That is, the impedance found by turning off the signal source ''I<sub>S</sub>'' = 0, inserting a test current in the emitter lead ''I<sub>x</sub>'', finding the voltage across the test source ''V<sub>x</sub>'', and finding ''R<sub>out</sub> = V<sub>x</sub> / I<sub>x</sub>''.</ref> | ||

</ref> | |||

===Load voltage and load current=== | |||

The | The gain derived above is the current gain at the collector of the output transistor. To relate this gain to the gain when voltage is the output of the amplifier, notice that the output voltage at the load ''R<sub>L</sub>'' is related to the collector current by [[Ohm's law]] as ''v<sub>L</sub> = i<sub>C</sub> (R<sub>C2</sub> // R<sub>L</sub>)''. Consequently, the transresistance gain ''v<sub>L</sub> / i<sub>S</sub>'' is found by multiplying the current gain by ''R<sub>C2</sub> // R<sub>L</sub>'': | ||

</ | |||

< | ::<math> \frac {v_L} {i_S} = A_{FB} (R_{C2}//R_L ) \ . </math> | ||

</ | |||

Similarly, if the output of the amplifier is taken to be the current in the load resistor ''R<sub>L</sub>'', [[current division]] determines the load current, and the gain is then: | |||

< | ::<math> \frac {i_L} {i_S} = A_{FB} \frac {R_{C2}} {R_{C2} + R_L} \ . </math> | ||

</ | |||

}} | {{Howto|section|date=March 2011}} | ||

{{Unreferenced|section|date=March 2011}} | |||

=== Is the main amplifier block a two port? === | |||

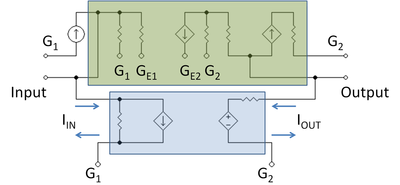

[[Image:Two-port ground arrangement.PNG|thumbnail|400px|Figure 7: Amplifier with ground connections labeled by ''G''. The feedback network satisfies the port conditions.]] | |||

Some complications follow, intended for the attentive reader. | |||

Figure 7 shows the small-signal schematic with the main amplifier and the feedback two-port in shaded boxes. The two-port satisfies the [[Two-port network|port conditions]]: at the input port, ''I''<sub>in</sub> enters and leaves the port, and likewise at the output, ''I''<sub>out</sub> enters and leaves. The main amplifier is shown in the upper shaded box. The ground connections are labeled. | |||

< | |||

< | Figure 7 shows the interesting fact that the main amplifier does not satisfy the port conditions at its input and output unless the ground connections are chosen to make that happen. For example, on the input side, the current entering the main amplifier is ''I''<sub>S</sub>. This current is divided three ways: to the feedback network, to the bias resistor ''R''<sub>B</sub> and to the base resistance of the input transistor ''r''<sub>π</sub>. To satisfy the port condition for the main amplifier, all three components must be returned to the input side of the main amplifier, which means all the ground leads labeled ''G''<sub>1</sub> must be connected, as well as emitter lead ''G''<sub>E1</sub>. Likewise, on the output side, all ground connections ''G''<sub>2</sub> must be connected and also ground connection ''G''<sub>E2</sub>. Then, at the bottom of the schematic, underneath the feedback two-port and outside the amplifier blocks, ''G''<sub>1</sub> is connected to ''G''<sub>2</sub>. That forces the ground currents to divide between the input and output sides as planned. Notice that this connection arrangement ''splits the emitter'' of the input transistor into a base-side and a collector-side – a physically impossible thing to do, but electrically the circuit sees all the ground connections as one node, so this fiction is permitted. | ||

< | |||

< | |||

</ | |||

Of course, the way the ground leads are connected makes no difference to the amplifier (they are all one node), but it makes a difference to the port conditions. That is a weakness of this approach: the port conditions are needed to justify the method, but the circuit really is unaffected by how currents are traded among ground connections. | |||

<ref | However, if there is '''no possible arrangement''' of ground conditions that will lead to the port conditions, the circuit might not behave the same way.<ref>The equivalence of the main amplifier block to a two-port network guarantees that performance factors work, but without that equivalence they may work anyway. For example, in some cases the circuit can be shown to be equivalent to another circuit that is a two port, by "cooking up" different circuit parameters that are functions of the original ones. There is no end to creativity!</ref> The improvement factors ( 1 + β<sub>FB</sub> A<sub>OL</sub>) for determining input and output impedance might not work. This situation is awkward, because a failure to make a two-port may reflect a real problem (it just is not possible), or reflect a lack of imagination (for example, just did not think of splitting the emitter node in two). As a consequence, when the port conditions are in doubt, at least two approaches are possible to establish whether improvement factors are accurate: either simulate an example using [[SPICE|Spice]] and compare results with use of an improvement factor, or calculate the impedance using a test source and compare results. | ||

</ | |||

A more radical choice is to drop the two-port approach altogether, and use [[return ratio]]s. That choice might be advisable if small-signal device models are complex, or are not available (for example, the devices are known only numerically, perhaps from measurement or from [[SPICE]] simulations). | |||

==References== | |||

{{Reflist}} | |||

}} | |||

Revision as of 18:05, 23 June 2011

A negative feedback amplifier (or more commonly simply a feedback amplifier) is an amplifier a fraction of the output of which is combined with the input so that a negative feedback opposes the original signal. The applied negative feedback improves performance (gain stability, linearity, frequency response, step response) and reduces sensitivity to parameter variations due to manufacturing or environment. Because of these advantages, negative feedback is used in this way in many amplifiers and control systems.[1]

A negative feedback amplifier is a system of three elements (see Figure 1): an amplifier with gain AOL, an attenuating feedback network with a constant β < 1 and a summing circuit acting as a subtractor (the circle in the figure). The amplifier is the only obligatory; the other elements may be omitted in some cases. For example, in a voltage (emitter, source, op-amp) follower the feedback network and the summing circuit are not necessary.

Overview

Fundamentally, all electronic devices used to provide power gain (e.g. vacuum tubes, bipolar transistors, MOS transistors) are nonlinear. Negative feedback allows gain to be traded for higher linearity (reducing distortion), amongst other things. If not designed correctly amplifiers with negative feedback can become unstable, resulting in unwanted behavior, such as oscillation. The Nyquist stability criterion developed by Harry Nyquist of Bell Laboratories can be used to study the stability of feedback amplifiers.

Feedback amplifiers share these properties:[2]

Pros:

- Can increase or decrease input impedance (depending on type of feedback)

- Can increase or decrease output impedance (depending on type of feedback)

- Reduces distortion (increases linearity)

- Increases the bandwidth

- Desensitizes gain to component variations

- Can control step response of amplifier

Cons:

- May lead to instability if not designed carefully

- The gain of the amplifier decreases

- The input and output impedances of the amplifier with feedback (the closed-loop amplifier) become sensitive to the gain of the amplifier without feedback (the open-loop amplifier); that exposes these impedances to variations in the open loop gain, for example, due to parameter variations or due to nonlinearity of the open-loop gain

History

The negative feedback amplifier was invented by Harold Stephen Black (US patent 2,102,671 (issued in 1937)[3] ) while a passenger on the Lackawanna Ferry (from Hoboken Terminal to Manhattan) on his way to work at Bell Laboratories (historically located in Manhattan instead of New Jersey in 1927) on August 2, 1927. Black had been toiling at reducing distortion in repeater amplifiers used for telephone transmission. On a blank space in his copy of The New York Times,[4] he recorded the diagram found in Figure 1, and the equations derived below.[5] Black submitted his invention to the U. S. Patent Office on August 8, 1928, and it took more than nine years for the patent to be issued. Black later wrote: "One reason for the delay was that the concept was so contrary to established beliefs that the Patent Office initially did not believe it would work."[6]

Classical feedback

Gain reduction

Below, the voltage gain of the amplifier with feedback, the closed-loop gain Afb, is derived in terms of the gain of the amplifier without feedback, the open-loop gain AOL and the feedback factor β, which governs how much of the output signal is applied to the input. See Figure 1, top right. The open-loop gain AOL in general may be a function of both frequency and voltage; the feedback parameter β is determined by the feedback network that is connected around the amplifier. For an operational amplifier two resistors forming a voltage divider may be used for the feedback network to set β between 0 and 1. This network may be modified using reactive elements like capacitors or inductors to (a) give frequency-dependent closed-loop gain as in equalization/tone-control circuits or (b) construct oscillators. The gain of the amplifier with feedback is derived below in the case of a voltage amplifier with voltage feedback.

Without feedback, the input voltage V'in is applied directly to the amplifier input. The according output voltage is

Suppose now that an attenuating feedback loop applies a fraction β.Vout of the output to one of the subtractor inputs so that it subtracts from the circuit input voltage Vin applied to the other subtractor input. The result of subtraction applied to the amplifier input is

Substituting for V'in in the first expression,

Rearranging

Then the gain of the amplifier with feedback, called the closed-loop gain, Afb is given by,

If AOL >> 1, then Afb ≈ 1 / β and the effective amplification (or closed-loop gain) Afb is set by the feedback constant β, and hence set by the feedback network, usually a simple reproducible network, thus making linearizing and stabilizing the amplification characteristics straightforward. Note also that if there are conditions where β AOL = −1, the amplifier has infinite amplification – it has become an oscillator, and the system is unstable. The stability characteristics of the gain feedback product β AOL are often displayed and investigated on a Nyquist plot (a polar plot of the gain/phase shift as a parametric function of frequency). A simpler, but less general technique, uses Bode plots.

The combination L = β AOL appears commonly in feedback analysis and is called the loop gain. The combination ( 1 + β AOL ) also appears commonly and is variously named as the desensitivity factor or the improvement factor.

Bandwidth extension

Feedback can be used to extend the bandwidth of an amplifier (speed it up) at the cost of lowering the amplifier gain.[7] Figure 2 shows such a comparison. The figure is understood as follows. Without feedback the so-called open-loop gain in this example has a single time constant frequency response given by

where fC is the cutoff or corner frequency of the amplifier: in this example fC = 104 Hz and the gain at zero frequency A0 = 105 V/V. The figure shows the gain is flat out to the corner frequency and then drops. When feedback is present the so-called closed-loop gain, as shown in the formula of the previous section, becomes,

The last expression shows the feedback amplifier still has a single time constant behavior, but the corner frequency is now increased by the improvement factor ( 1 + β A0 ), and the gain at zero frequency has dropped by exactly the same factor. This behavior is called the gain-bandwidth tradeoff. In Figure 2, ( 1 + β A0 ) = 103, so Afb(0)= 105 / 103 = 100 V/V, and fC increases to 104 × 103 = 107 Hz.

Multiple poles

When the open-loop gain has several poles, rather than the single pole of the above example, feedback can result in complex poles (real and imaginary parts). In a two-pole case, the result is peaking in the frequency response of the feedback amplifier near its corner frequency, and ringing and overshoot in its step response. In the case of more than two poles, the feedback amplifier can become unstable, and oscillate. See the discussion of gain margin and phase margin. For a complete discussion, see Sansen.[8]

Asymptotic gain model

In the above analysis the feedback network is unilateral. However, real feedback networks often exhibit feed forward as well, that is, they feed a small portion of the input to the output, degrading performance of the feedback amplifier. A more general way to model negative feedback amplifiers including this effect is with the asymptotic gain model.

Feedback and amplifier type

Amplifiers use current or voltage as input and output, so four types of amplifier are possible. See classification of amplifiers. Any of these four choices may be the open-loop amplifier used to construct the feedback amplifier. The objective for the feedback amplifier also may be any one of the four types of amplifier, not necessarily the same type as the open-loop amplifier. For example, an op amp (voltage amplifier) can be arranged to make a current amplifier instead. The conversion from one type to another is implemented using different feedback connections, usually referred to as series or shunt (parallel) connections.[9][10] See the table below.

| Feedback amplifier type | Input connection | Output connection | Ideal feedback | Two-port feedback |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | Shunt | Series | CCCS | g-parameter |

| Transresistance | Shunt | Shunt | CCVS | y-parameter |

| Transconductance | Series | Series | VCCS | z-parameter |

| Voltage | Series | Shunt | VCVS | h-parameter |

The feedback can be implemented using a two-port network. There are four types of two-port network, and the selection depends upon the type of feedback. For example, for a current feedback amplifier, current at the output is sampled and combined with current at the input. Therefore, the feedback ideally is performed using an (output) current-controlled current source (CCCS), and its imperfect realization using a two-port network also must incorporate a CCCS, that is, the appropriate choice for feedback network is a g-parameter two-port.

Two-port analysis of feedback

One approach to feedback is the use of return ratio. Here an alternative method used in most textbooks[11][12][13] is presented by means of an example treated in the article on asymptotic gain model.

Figure 3 shows a two-transistor amplifier with a feedback resistor Rf. The aim is to analyze this circuit to find three items: the gain, the output impedance looking into the amplifier from the load, and the input impedance looking into the amplifier from the source.

Replacement of the feedback network with a two-port

The first step is replacement of the feedback network by a two-port. Just what components go into the two-port?

On the input side of the two-port we have Rf. If the voltage at the right side of Rf changes, it changes the current in Rf that is subtracted from the current entering the base of the input transistor. That is, the input side of the two-port is a dependent current source controlled by the voltage at the top of resistor R2.

One might say the second stage of the amplifier is just a voltage follower, transmitting the voltage at the collector of the input transistor to the top of R2. That is, the monitored output signal is really the voltage at the collector of the input transistor. That view is legitimate, but then the voltage follower stage becomes part of the feedback network. That makes analysis of feedback more complicated.

An alternative view is that the voltage at the top of R2 is set by the emitter current of the output transistor. That view leads to an entirely passive feedback network made up of R2 and Rf. The variable controlling the feedback is the emitter current, so the feedback is a current-controlled current source (CCCS). We search through the four available two-port networks and find the only one with a CCCS is the g-parameter two-port, shown in Figure 4. The next task is to select the g-parameters so that the two-port of Figure 4 is electrically equivalent to the L-section made up of R2 and Rf. That selection is an algebraic procedure made most simply by looking at two individual cases: the case with V1 = 0, which makes the VCVS on the right side of the two-port a short-circuit; and the case with I2 = 0. which makes the CCCS on the left side an open circuit. The algebra in these two cases is simple, much easier than solving for all variables at once. The choice of g-parameters that make the two-port and the L-section behave the same way are shown in the table below.

| g11 | g12 | g21 | g22 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ' |

Small-signal circuit

The next step is to draw the small-signal schematic for the amplifier with the two-port in place using the hybrid-pi model for the transistors. Figure 5 shows the schematic with notation R3 = RC2 // RL and R11 = 1 / g11, R22 = g22 .

Loaded open-loop gain

Figure 3 indicates the output node, but not the choice of output variable. A useful choice is the short-circuit current output of the amplifier (leading to the short-circuit current gain). Because this variable leads simply to any of the other choices (for example, load voltage or load current), the short-circuit current gain is found below.

First the loaded open-loop gain is found. The feedback is turned off by setting g12 = g21 = 0. The idea is to find how much the amplifier gain is changed because of the resistors in the feedback network by themselves, with the feedback turned off. This calculation is pretty easy because R11, RB, and rπ1 all are in parallel and v1 = vπ. Let R1 = R11 // RB // rπ1. In addition, i2 = −(β+1) iB. The result for the open-loop current gain AOL is:

Gain with feedback

In the classical approach to feedback, the feedforward represented by the VCVS (that is, g21 v1) is neglected.[14] That makes the circuit of Figure 5 resemble the block diagram of Figure 1, and the gain with feedback is then:

where the feedback factor βFB = −g12. Notation βFB is introduced for the feedback factor to distinguish it from the transistor β.

Input and output resistances

First, a digression on how two-port theory approaches resistance determination, and then its application to the amplifier at hand.

Background on resistance determination

Figure 6 shows an equivalent circuit for finding the input resistance of a feedback voltage amplifier (left) and for a feedback current amplifier (right). These arrangements are typical Miller theorem applications.

In the case of the voltage amplifier, the output voltage βVout of the feedback network is applied in series and with an opposite polarity to the input voltage Vx travelling over the loop (but in respect to ground, the polarities are the same). As a result, the effective voltage across and the current through the amplifier input resistance Rin decrease so that the circuit input resistance increases (one might say that Rin apparently increases). Its new value can be calculated by applying Miller theorem (for voltages) or the basic circuit laws. Thus Kirchhoff's voltage law provides:

where vout = Av vin = Av Ix Rin. Substituting this result in the above equation and solving for the input resistance of the feedback amplifier, the result is:

The general conclusion to be drawn from this example and a similar example for the output resistance case is:

A series feedback connection at the input (output) increases the input (output) resistance by a factor ( 1 + β AOL ), where AOL = open loop gain.

On the other hand, for the current amplifier, the output current βIout of the feedback network is applied in parallel and with an opposite direction to the input current Ix. As a result, the total current flowing through the circuit input (not only through the input resistance Rin) increases and the voltage across it decreases so that the circuit input resistance decreases (Rin apparently decreases). Its new value can be calculated by applying the dual Miller theorem (for currents) or the basic Kirchhoff's laws:

where iout = Ai iin = Ai Vx / Rin. Substituting this result in the above equation and solving for the input resistance of the feedback amplifier, the result is:

The general conclusion to be drawn from this example and a similar example for the output resistance case is:

A parallel feedback connection at the input (output) decreases the input (output) resistance by a factor ( 1 + β AOL ), where AOL = open loop gain.

These conclusions can be generalized to treat cases with arbitrary Norton or Thévenin drives, arbitrary loads, and general two-port feedback networks. However, the results do depend upon the main amplifier having a representation as a two-port – that is, the results depend on the same current entering and leaving the input terminals, and likewise, the same current that leaves one output terminal must enter the other output terminal.

A broader conclusion to be drawn, independent of the quantitative details, is that feedback can be used to increase or to decrease the input and output impedances.

Application to the example amplifier

These resistance results now are applied to the amplifier of Figure 3 and Figure 5. The improvement factor that reduces the gain, namely ( 1 + βFB AOL), directly decides the effect of feedback upon the input and output resistances of the amplifier. In the case of a shunt connection, the input impedance is reduced by this factor; and in the case of series connection, the impedance is multiplied by this factor. However, the impedance that is modified by feedback is the impedance of the amplifier in Figure 5 with the feedback turned off, and does include the modifications to impedance caused by the resistors of the feedback network.

Therefore, the input impedance seen by the source with feedback turned off is Rin = R1 = R11 // RB // rπ1, and with the feedback turned on (but no feedforward)

where division is used because the input connection is shunt: the feedback two-port is in parallel with the signal source at the input side of the amplifier. A reminder: AOL is the loaded open loop gain found above, as modified by the resistors of the feedback network.

The impedance seen by the load needs further discussion. The load in Figure 5 is connected to the collector of the output transistor, and therefore is separated from the body of the amplifier by the infinite impedance of the output current source. Therefore, feedback has no effect on the output impedance, which remains simply RC2 as seen by the load resistor RL in Figure 3.[15][16]

If instead we wanted to find the impedance presented at the emitter of the output transistor (instead of its collector), which is series connected to the feedback network, feedback would increase this resistance by the improvement factor ( 1 + βFB AOL).[17]

Load voltage and load current

The gain derived above is the current gain at the collector of the output transistor. To relate this gain to the gain when voltage is the output of the amplifier, notice that the output voltage at the load RL is related to the collector current by Ohm's law as vL = iC (RC2 // RL). Consequently, the transresistance gain vL / iS is found by multiplying the current gain by RC2 // RL:

Similarly, if the output of the amplifier is taken to be the current in the load resistor RL, current division determines the load current, and the gain is then:

Template:Howto Template:Unreferenced

Is the main amplifier block a two port?

Some complications follow, intended for the attentive reader.

Figure 7 shows the small-signal schematic with the main amplifier and the feedback two-port in shaded boxes. The two-port satisfies the port conditions: at the input port, Iin enters and leaves the port, and likewise at the output, Iout enters and leaves. The main amplifier is shown in the upper shaded box. The ground connections are labeled.

Figure 7 shows the interesting fact that the main amplifier does not satisfy the port conditions at its input and output unless the ground connections are chosen to make that happen. For example, on the input side, the current entering the main amplifier is IS. This current is divided three ways: to the feedback network, to the bias resistor RB and to the base resistance of the input transistor rπ. To satisfy the port condition for the main amplifier, all three components must be returned to the input side of the main amplifier, which means all the ground leads labeled G1 must be connected, as well as emitter lead GE1. Likewise, on the output side, all ground connections G2 must be connected and also ground connection GE2. Then, at the bottom of the schematic, underneath the feedback two-port and outside the amplifier blocks, G1 is connected to G2. That forces the ground currents to divide between the input and output sides as planned. Notice that this connection arrangement splits the emitter of the input transistor into a base-side and a collector-side – a physically impossible thing to do, but electrically the circuit sees all the ground connections as one node, so this fiction is permitted.

Of course, the way the ground leads are connected makes no difference to the amplifier (they are all one node), but it makes a difference to the port conditions. That is a weakness of this approach: the port conditions are needed to justify the method, but the circuit really is unaffected by how currents are traded among ground connections.

However, if there is no possible arrangement of ground conditions that will lead to the port conditions, the circuit might not behave the same way.[18] The improvement factors ( 1 + βFB AOL) for determining input and output impedance might not work. This situation is awkward, because a failure to make a two-port may reflect a real problem (it just is not possible), or reflect a lack of imagination (for example, just did not think of splitting the emitter node in two). As a consequence, when the port conditions are in doubt, at least two approaches are possible to establish whether improvement factors are accurate: either simulate an example using Spice and compare results with use of an improvement factor, or calculate the impedance using a test source and compare results.

A more radical choice is to drop the two-port approach altogether, and use return ratios. That choice might be advisable if small-signal device models are complex, or are not available (for example, the devices are known only numerically, perhaps from measurement or from SPICE simulations).

References

- ↑ Kuo, Benjamin C & Farid Golnaraghi (2003). Automatic control systems, Eighth edition. NY: Wiley. ISBN 0471134767.

- ↑ Palumbo, Gaetano & Salvatore Pennisi (2002). Feedback amplifiers: theory and design. Boston/Dordrecht/London: Kluwer Academic. ISBN 0792376439.

- ↑ .. Retrieved on 2005-10-24. Template:Dead link

- ↑ Currently on display at Bell Laboratories in Mountainside, New Jersey

- ↑ Waldhauer, Fred (1982). Feedback. NY: Wiley. ISBN 0471053198.

- ↑ Black, Harold. "Inventing the negative feedback amplifier", IEEE Spectrum, Dec. 1977.

- ↑ RW Brodersen Analog circuit design: lectures on stability

- ↑ Willy M. C. Sansen (2006). Analog design essentials. New York; Berlin: Springer, §0513-§0533, p. 155–165. ISBN 0-387-25746-2.

- ↑ Ashok K. Goel Feedback topologies

- ↑ Zimmer T & Geoffreoy D: Feedback amplifier

- ↑ Vivek Subramanian: Lectures on feedback

- ↑ P R Gray, P J Hurst, S H Lewis, and R G Meyer (2001). Analysis and Design of Analog Integrated Circuits, Fourth Edition. New York: Wiley, 586–587. ISBN 0-471-32168-0.

- ↑ A. S. Sedra and K.C. Smith (2004). Microelectronic Circuits, Fifth Edition. New York: Oxford, Example 8.4, pp. 825–829 and PSpice simulation pp. 855–859. ISBN 0-19-514251-9.

- ↑ If the feedforward is included, its effect is to cause a modification of the open-loop gain, normally so small compared to the open-loop gain itself that it can be dropped. Notice also that the main amplifier block is unilateral.

- ↑ The use of the improvement factor ( 1 + βFB AOL) requires care, particularly for the case of output impedance using series feedback. See Jaeger, note below.

- ↑ R.C. Jaeger and T.N. Blalock (2006). Microelectronic Circuit Design, Third Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-319163-8.

- ↑ That is, the impedance found by turning off the signal source IS = 0, inserting a test current in the emitter lead Ix, finding the voltage across the test source Vx, and finding Rout = Vx / Ix.

- ↑ The equivalence of the main amplifier block to a two-port network guarantees that performance factors work, but without that equivalence they may work anyway. For example, in some cases the circuit can be shown to be equivalent to another circuit that is a two port, by "cooking up" different circuit parameters that are functions of the original ones. There is no end to creativity!