Hertzsprung-Russell diagram: Difference between revisions

George Swan (talk | contribs) (ce) |

George Swan (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

All but the most massive stars that are still shining from energy derived from [[Hydrogen fusion]] are said to be on the [[main sequence]] of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. | All but the most massive stars that are still shining from energy derived from [[Hydrogen fusion]] are said to be on the [[main sequence]] of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. | ||

http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/ast122/lectures/lec11.html | |||

Revision as of 03:40, 9 April 2022

- there is a noindex on this article, as it is not ready yet...

Hertzsprung-Russell diagrams are used by astronomers to place the size, luminosity and surface temperatures of stars into context. The diagram plots surface temperature along the X-axis, and luminosity along the Y-axis.

The vast majority of stars are relatively small dim stars with low surface temperatures, known as red dwarfs. They range in mass from approximately half the mass of Sol, our sun, to slightly less than ten percent the mass of Sol.

Hertzsprung-Russell diagrams generally show several roughly horizontal bands, composed of dots, representing actual stars. Most of the stars lie along one band, that stretches from the top right corner, to the lower left corner. This band is called the "main sequence". The stars on the right hand end of this band are both luminous, and have high surface temperatures. The stars in the lower left hand end of this band are dim, and red, because they have low surface temperatures.

The main sequence stars are all in the longest phase of their lives - the phase where they shine from energy produced through Hydrogen fusion - the nuclear process where the nuclei of several Hydrogen atoms fuse to form an atom of Helium. Every star above the main sequence will be a luminous giant star, near the end of their lives, shining from energy produced through fusing heavier elements.

A star's luminosity is inversely related to the cube of the star's mass. The frugal rate at which the small, dim red dwarfs turn their Hydrogen to Helium make them long lived, and the Universe is too young for any red dwarf to have consumed all its Hydrogen fuel. The smallest red dwarfs are expected to keep shining for one trillion years.

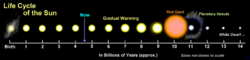

Sol is 4.5 billion years old, and is expected to have exhausted all its accessable Hydrogen in another 5 billion years, or so. Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, is slightly more than twice as massive as Sol, and it expected to exhaust its Hydrogen fuel within one billion years.

When red dwarf stars eventually exhaust their Hydrogen fuel they will shrink, and grow dim. Larger stars, including Sol, are massive enough that, as they shrink there is enough pressure in their core to start fusing Helium into higher elements.

All but the most massive stars that are still shining from energy derived from Hydrogen fusion are said to be on the main sequence of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram.