American Revolution: Difference between revisions

imported>Subpagination Bot m (Add {{subpages}} and remove any categories (details)) |

imported>Richard Jensen mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The '''American Revolution''' was the political and military action of the American colonists who overthrew British control, and created a new nation in 1776, the "United States of America." | The '''American Revolution''' was the political and military action of the American colonists who overthrew British control, and created a new nation in 1776, the "United States of America." | ||

This article deals with political issues. For the military history see [[American Revolution, military history]] and [[American Revolution, naval history]] | This article deals with political issues, especially the national politics conducted in the name of the [[Articles of Confederation]]. For the military history see [[American Revolution, military history]] and [[American Revolution, naval history]] | ||

==Tensions rise after 1763== | ==Tensions rise after 1763== | ||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

* [[American Revolution, military history]] | * [[American Revolution, military history]] | ||

* [[American Revolution, naval history]] | * [[American Revolution, naval history]] | ||

* [[Articles of Confederation]] | |||

* [[Declaration of Independence]] | |||

==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

| Line 85: | Line 86: | ||

* Lancaster, Bruce. ''The American Revolution'' (American Heritage Library) (ISBN: 0828102813) (1985), heavily illustrated | * Lancaster, Bruce. ''The American Revolution'' (American Heritage Library) (ISBN: 0828102813) (1985), heavily illustrated | ||

* Martin, James Kirby. ''In the Course of Human Events: An Interpretive Exploration of the American Revolution'' (1979), short survey (ISBN: 0882957953) | * Martin, James Kirby. ''In the Course of Human Events: An Interpretive Exploration of the American Revolution'' (1979), short survey (ISBN: 0882957953) | ||

* Middlekauff, Robert. ''The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789'' ( | * Middlekauff, Robert. ''The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789'' (2nd ed 2007) [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=84633736 online edition] | ||

* Miller, John C. ''Triumph of Freedom, 1775-1783.'' (1946) [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=14559136 online edition] | * Miller, John C. ''Triumph of Freedom, 1775-1783.'' (1946) [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=14559136 online edition] | ||

* Royster, Charles. ''A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character,'' 1979. | * Royster, Charles. ''A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character,'' 1979. | ||

Revision as of 23:04, 1 October 2007

The American Revolution was the political and military action of the American colonists who overthrew British control, and created a new nation in 1776, the "United States of America."

This article deals with political issues, especially the national politics conducted in the name of the Articles of Confederation. For the military history see American Revolution, military history and American Revolution, naval history

Tensions rise after 1763

After the Seven Years War the French threat ended. London decided to start taxing the colonies to pay for past and future wars, and imposed new controls on the colonial economy and on westward expansion. London insisted that the colonists pay a share of the cost of empire through new taxes, but refused to allow representation in Parliament. The Americans rallied around the idea that no Englishman could be taxed without his consent, that is, "No taxation without representation."

Ominously London sent thousands of regular army troops--was this to protect the colonists from nonexistent threats, or to protect the Royal officials from the anger of the people? Nothing seemed more dangerous to the precious political liberties of the Americans than the sort of standing army Britain was forcing upon them. The colonists responded by setting up their own shadow government, including local committees and (beginning in 1774) a Continental Congress. The Empire thought it knew how to suppress rebellions--in 1715 and 1745 it had ruthlessly crushed the Highlanders in Scotland; in the 17th century it had taken control of Ireland in campaigns that killed thousands of Catholic rebels and left the Protestants in total domination.

Stamp Act 1765: American unite

Boston Massacre

First Continental Congress

In Search of Independence: 1774-1776

The revolution occurred in the hearts and minds of Americans in 1774-1776 as they realized that continued subservience to the British Empire was impossible. Tensions came to a head in Massachusetts. In late 1773 the Boston radicals disguised as Indians dumped a shipment of tea into the harbor in protest. This Boston Tea Party angered the British leadership and next spring Parliament passed the Coercive Acts that imposed near martial law and suspended traditional civil liberties and economic freedom. Congress denounced the Acts, called for boycotts of British goods, and recommended that the militias ready their weapons. Georgia became the 13th colony represented in the Congress.

Canada and 16 smaller British colonies in North America remained loyal. The French Catholics in Canada much preferred the tolerance of London to the anti-Catholic Yankees; they stayed loyal, as did the wealthy sugar planters who controlled the numerous West Indian colonies. East Florida, West Florida and Newfoundland were so small, so new, and so dominated by the British army and navy that they stayed loyal. Nova Scotia (just north of Maine) was the curious case. It had been settled largely by New Englanders, who favored Congress. Yet it was an isolated island, easily controlled by the Royal Navy from its powerful base in Halifax. Protests were put down, and the people stayed neutral, pouring their emotions into religious revival rather than revolution.

The 13 revolting colonies were the largest, richest, and most developed in the Empire. London had no intention of letting them go free. General Thomas Gage fortified Boston and raided nearby towns where rebels had stored munitions. The people of Massachusetts responded by setting up a provisional government, training militia units, and detecting and suppressing Loyalists and spies. A system of "minute men" was established, so that any alarm would be answered immediately.

The Americans had sympathizers in Britain, but not enough. Parliament rejected conciliation by a 3 to 1 margin, and Gage was ordered to aggressively enforce the Coercion laws. More troops arrived, along with the generals who would later replace Gage and command the main British armies during the war, Sir William Howe (fall 1775 to spring 1778), Sir Henry Clinton (1778 to 1782) and John Burgoyne. All of them failed at their mission--perhaps because political considerations in London made it impossible to remove careless generals who repeatedly lost tactical opportunities, quarreled or failed to coordinate with one another, and muffled the strategic designs that London drew up.

Washington took charge of the siege of Boston, June 1775-March 1776, and as Ellis (2005) shows this was the formative event in his development as a military and political leader. The siege revealed the enormous logistical problems the army had to overcome. Washington met the challenge with his trademark determination, leadership ability, and sound decisionmaking. He also, however, exhibited a stubborn, aloof, severe personality that "virtually precluded intimacy." Washington, dubbed "His Excellency" by the adoring American public, also came to know and evaluate many of his future staff members and lieutenants during the siege.

New Nation 1776-1781

Diplomacy

Gender, race, class

Pybus (2005) estimates that about 20,000 slaves defected to the British, of whom about 8,000 died from disease or wounds or were recaptured by the Patriots, and 12,000 left the country at the end of the war, for freedom in Canada or slavery in the West Indies.

Baller (2006) examines family dynamics and mobilization for the Revolution in central Massachusetts. He reports that warfare and the farming culture were sometimes incompatible. Some militiamen found that farming life failed to prepare them for wartime stresses and the rigors of camp life. Rugged individualism and military regimentation did not always mesh. Birth order shaped military recruitment, reagring older and younger sons. Family responsibilities and a suffocating patriarchy sometimes impeded mobilization. Harvesting duties and family emergencies forced some to have to choose between home and the Patriot cause. Family ties sometimes involved tensions between patriots and their loyalist relatives. The Revolution's impact on patriarchy and inheritance patterns was toward more equalitarianism.

McDonnell, (2006) shows the major complicating factor in Virginia's efforts to raise forces for the war, the conflicting interests of several distinct social classes among whites in the colony more strongly militated against a "unified" commitment to military service. The Assembly had to weight and balance the competing demands of elite slaveowning planters, slaveholding and nonslaveholding "middling sorts," yeoman farmers, and indentured servants, among others. Its solution involved deferments, taxes, military service substitute, and conscription legislation. Unresolved class conflict, however, rendered these laws ineffective. Violent protests, conscript evasion, and large-scale desertion left Virginia's contributions to the war effort at embarassingly low levels. As late as the 1781 Battle of Yorktown, Virginia continued to be mired in class divisiveness as its native son, George Washington, made desperate appeals for troops.

Loyalists

See Loyalists

Peace and new Constitution, 1781-1789

See also

- American Revolution, military history

- American Revolution, naval history

- Articles of Confederation

- Declaration of Independence

Bibliography

Reference books

- Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution. (2000). 778pp.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, and Richard A. Ryerson, eds. The Encyclopedia of the American Revolutionary War: A Political, Social, and Military History (ABC-CLIO, 2006) 5 volume paper and online editions; 1000 entries by 150 experts, covering all topics

- Boatner III, Mark M. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (1966); excellent guide to details; expanded 3 vol edition (2006)

- Barnes, Ian and Charles Royster. The Historical Atlas of the American Revolution (2000)

- Cappon, Lester. Atlas of the American Revolution (1976); best coverage of society, economics and politics; thin on military

Surveys

- Alden, John R. A History of the American Revolution (1989), general survey; strong on military (ISBN: 0306803666)

- Alden, John R. American Revolution: 1775-1783 (1976), shorter survey with more on military

- Brown, Richard D. ed. Major Problems in the Era of the American Revolution 1992, excerpts from primary and secondary sources

- Ferling; John. Setting the World Ablaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the American Revolution Oxford University Press, 2002 online edition

- Ferling, John ed., The World Turned Upside Down: The American

Victory in the War of Independence (1988).

- Higginbotham, Don. The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763–1789 (1971, 1983). an analytical history of the war online via ACLS Humanities E-Book.

- Lancaster, Bruce. The American Revolution (American Heritage Library) (ISBN: 0828102813) (1985), heavily illustrated

- Martin, James Kirby. In the Course of Human Events: An Interpretive Exploration of the American Revolution (1979), short survey (ISBN: 0882957953)

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789 (2nd ed 2007) online edition

- Miller, John C. Triumph of Freedom, 1775-1783. (1946) online edition

- Royster, Charles. A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character, 1979.

- Weintraub, Stanley. Iron Tears: America's Battle for Freedom, Britain's Quagmire: 1775-1783. Free Pr., 2005. 375 pp.

Surveys: British perspective

- Black, Jeremy. War for America: The Fight for Independence, 1991. British perspective

- Lecky, William Edward Hartpole. The American Revolution, 1763-1783 1898 by leading British scholar; online edition; Google edition

- Marston, Daniel. The American Revolution, 1774-1783. Routledge. 2003. 95 pp survey online edition

- Mackesy, Piers. War for America, 2nd edition, 1993. British perspective

- Wrong, George M. Canada and the American Revolution: The Disruption of the First British Empire. 1935. by Canadian scholar online edition

Coming of Revolution

- Becker, Carl. The Eve of the Revolution: A Chronicle of the Breach with England. (1918) online edition short survey by leading scholar

- Gipson, Lawrence Henry; The Coming of the Revolution, 1763-1775 (1954) online edition

- Jensen, Merrill. The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution 1763-1776. (2004)

- Labaree, Benjamin Woods. The Boston Tea Party (1964).

- Maier, Pauline. From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776 (1972).

- Miller, John C. Origins of the American Revolution (1943) online edition

- Rossiter, Clinton. The First American Revolution;: The American Colonies on the eve of independence (1966)

- Ray, Raphael. The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord. (2002) emphasis on rural Massachusetts

- John C. Wahlke; ed. The Causes of the American Revolution 1967 short excerpts. online edition

Atlantic and Empire

- Brooke, John. George III (1972) pp 267-349

- Flavell, Julie and Conway, Stephen, eds. Britain and America Go to War: The Impact of War and Warfare in Anglo-America, 1754-1815. U. Press of Florida, 2004. 284 pp.

- Gould, Eliga H. and Onuf, Peter S., eds. Empire and Nation: The American Revolution in the Atlantic World. Johns Hopkins U. Pr., 2005. 381 pp.

- Gruber, Ira D. "Lord Howe and Lord George Germain: British Politics and the Winning of American Independence." William and Mary Quarterly 1965 22(2): 225-243. Issn: 0043-5597 in Jstor

- Hay, Carla H. "Catharine Macaulay and the American Revolution." The Historian. 56#2 1994. pp 301+. online edition; she was an English writer and friend of America

- Marshall, P. J. ed., The Eighteenth Century, vol. 2 of Oxford History of the British Empire, ed. William Roger Louis

(1998)

- Marshall, Peter and Glyn Williams; The British Atlantic Empire before the American Revolution (1980) onine edition

- Morrison, Michael A. and Zook, Melinda S., eds. Revolutionary Currents: Nation Building in the Transatlantic World. 2004. 224 pp.

- Nelson, Paul David. "British Conduct of the American Revolutionary War: A Review of Interpretations," The Journal of American History, Vol. 65, No. 3 (Dec., 1978), pp. 623-653 in JSTOR

- Watson, J. Steven. The Reign of George III, 1760-1815. 1960. standard history of British politics. online edition

- Wrong, George M. Canada and the American Revolution: The Disruption of the First British Empire. 1935. online edition

Ideology and Republicanism

- Breen, T. H. "Ideology and Nationalism on the Eve of the American Revolution: Revisions Once More in Need of Revising," Journal of American History 84 (1997), 13–39. in JSTOR

- Foner, Eric. Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. (2nd ed 2005). 326 pp.

- Kloppenberg, James T. "The Virtues of Liberalism: Christianity, Republicanism, and Ethics in Early American Political Discourse," Journal of American History 74 (1987), 9–33. in JSTOR

- Larkin, Edward. Thomas Paine and the Literature of Revolution. Cambridge U. Pr., 2005. 215 pp.

- Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (1997)

- Moses Coit Tyler; The Literary History of the American Revolution, 1763-1783 (1897) online edition

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1992).

- Wood, Gordon S. The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (1969), a dense but highly influential study

African Americans

- Kaplan, Emma Nogrady, and Sidney Kaplan. The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution. (1989) online edition.

- Nash, Gary B. The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. (2005). 512 pp.

- Pybus, Cassadra. "Jefferson's Faulty Math: the Question of Slave Defections in the American Revolution." William and Mary Quarterly 2005 62(2): 243-264. Issn: 0043-5597 Fulltext: in History Cooperative

- Quarles, Benjamin. The Negro in the American Revolution (1961)

Women

- Berkin, Carol. Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence. Knopf, 2005. 197 pp.

- De Pauw, Linda Grant. "Women in Combat: the Revolutionary War Experience," Armed Forces and Society 7 (1981) 209-26

- Kerber, Linda K. Women of the Republic (1980)

- Kerber, Linda K. “History Will Do It No Justice: Women’s Lives in Revolutionary America” (1987) online at [1]

- Norton, Mary Beth. Liberty's Daughters The Revolutionary Experience of American Women 1750-1800 (2nd ed. 1996)

- Young, Alfred F. Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier. (2004). 417 pp.

Social and economic history

- Baller, William. "Farm Families and the American Revolution." Journal of Family History (2006) 31(1): 28-44. Issn: 0363-1990 Fulltext: online in Ebsco

- Breen, T. H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence Oxford U.P. 2004 online edition

- Doerflinger, Thomas M. A Vigorous Spirit of Enterprise: Merchants and Economic Development in Revolutionary Philadelphia (1986), 197-250; businessmen at war

- Jameson, J. Franklin. The American Revolution Considered as a Social Movement (1926) online edition emphasis on class warfare

- McDonnell, Michael A. "Class War: Class Struggles During the American Revolution in Virginia." William and Mary Quarterly 2006 63(2): 305-344. Issn: 0043-5597 Fulltext: online at History Cooperative

- Nettels, Curtis. The Emergence of a National Economy, 1775-1815 (1962); best overview of economic history

- Tiedemann, Joseph S. "Presbyterianism and the American Revolution in the Middle Colonies." Church History 2005 74(2): 306-344. Issn: 0009-6407 Fulltext: in Ebsco

- Volo, Dorothy Denneen, and James M. Volo; Daily Life during the American Revolution Greenwood Press, 2003 online edition

Loyalists

- Brown, Wallace. The King's Friends: The Composition and Motives of the American Loyalist Claimants (1965); says Loyalists comprised only 8 to 18% of the whites; included all socio-ecoomic backgrounds, esp urban, commercial, office-holding, professional, and Anglican

- Calhoon, Robert. The Loyalists in Revolutionary America (1965)

- Nelson, William H. The American Tories (1961) psychohistory; not so much loyalty as weakness--weak because of lack of organization; many were ethnic or religious minorities who looked to London for protection

- Smith, Paul H. Loyalists and Redcoats: A Study in British Revolutionary Policy, 1964.

- Van Tyne, Claude Halstead. The Loyalists in the American Revolution (1929) online edition

Loyalist Indians

- Calloway, Colin G. The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities (1995)

- Graymont, Barbara. The Iroquois in the American Revolution (1972)

- O'Donnell, James H. The Southern Indians in the American Revolution (1973)

- Washburn, Wilcomb E. "Indians and the American Revolution," online

State, regional and local studies

- Countryman, Edward. A People in Revolution: The American Revolution and Political Society in New York, 1760–1790 (1981)

- Crow, Jeffrey J., Larry E. Tise, eds; The Southern Experience in the American Revolution (1978) online edition

- Gross, Robert A. The Minutemen and their World (1976). re Massachusetts

- Hawke, David. In the Midst of a Revolution. (1961) on Philadelphia. online edition

- Isaac, Rhys. The Transformation of Virginia, 1740–1790 (1982); highly influential study

- Mitnick, Barbara J., ed. New Jersey in the American Revolution. (2005). 268 pp.

- Nevins, Allan. The American States during and after the Revolution, 1775-1789 (1927) online edition, highly detailed coverage of each state

- Selby, John E. The Revolution in Virginia, 1775-1783 (1988)

- Tiedemann, Joseph S. and Fingerhut, Eugene R., eds. The Other New York: The American Revolution beyond New York City, 1763-1787. (2005). 246 pp.

- Wilson, David K. The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775-1780. (2005). 341 pp.

Military history

see American Revolution, military history

- Alden, John R. American Revolution: 1775-1783 (1976)

- Black, Jeremy. War for America: The Fight for Independence, 1991. British perspective

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing (2004), Pulitzer prize winner; study of 1776-77 online excerpt

- Higginbotham, Don. The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763–1789 (1971, 1983). an analytical history of the war online via ACLS Humanities E-Book.

- McCullough, David. 1776. 386 pp.

- Martin, James Kirby, and Mark E. Lender, A Respectable Army: The Military Origin of the Republic, 1763–1789 (1982), short

- Ward, Christopher. The War of the Revolution, 2 vols., 1952, a good narrative of all the major battles.

- West Point Atlas

- Shy, John. A People Numerous and Armed: Reflections on the Military Struggle for American Independence, 1976.

see American Revolution, naval history

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer. The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783 (1890) 557 pages; probably the most influential history book ever written Google version

- Syrett, David. The Royal Navy in American Waters, 1989.

Diplomacy & France

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg. The Diplomacy of the American Revolution (1935) online edition

- Brown, John L. "Revolution and the Muse: the American War of Independence in Contemporary French Poetry." William and Mary Quarterly 1984 41(4): 592-614. Issn: 0043-5597 Fulltext in : Jstor

- Brecher, Frank W. Securing American Independence: John Jay and the French Alliance. Praeger Publishers, 2003. Pp. xiv, 327 online

- Chartrand, René, and Back, Francis. The French Army in the American War of Independence Osprey; 1991.

- Corwin, Edward S. French Policy and the American Alliance of 1778 Archon Books; 1962.

- Dull, Jonathan. A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution, 1985.

- Dull, Jonathan R. The French Navy and American Independence: A Study of Arms and Diplomacy 1774-1787 (1975)

- Ferling, John. “John Adams: Diplomat,” William and Mary Quarterly 51 (1994): 227–52. in JSTOR

- Gottschalk, Louis. Lafayette Comes to America 1935 online

- Gottschalk, Louis. Lafayette Joins the American Army (1937)

- Hoffman, Ronald and Albert, Peter J., ed. Peace and the Peacemakers: The Treaty of 1783. U. Press of Virginia, 1986. 263 pp.

- Hoffman, Ronald and Albert, Peter J., ed. Diplomacy and Revolution: The Franco-American Alliance of 1778. U. Press of Virginia, 1981. 200 pp.

- Hudson, Ruth Strong. The Minister from France: Conrad-Alexandre Gérard, 1729-1790. Lutz, 1994. 279 pp.

- Hutson, James H. John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution (1980)

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. "The Diplomacy of the American Revolution: the Perspective from France." Reviews in American History 1976 4(3): 385-390. Issn: 0048-7511 Fulltext in Jstor; review of Dull (1975)

- Kennett, Lee. The French Forces in America, 1780-1783. Greenwood, 1977. 188 pp.

- Kramer, Lloyd. Lafayette in Two Worlds: Public Cultures and Personal Identities in an Age of Revolutions. (1996). 355 pp.

- Newman, Simon, ed. Europe’s American Revolution. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. isbn 1-4039-8997-4.)

- Perkins, James Breck. France in the American Revolution 1911 online

- Popofsky, Linda S. and Sheldon, Marianne B. "French and American Women in the Age of Democratic Revolution, 1770-1815: a Comparative Perspective." History of European Ideas1987 8(4-5): 597-609. Issn: 0191-6599

- Pritchard, James. "French Strategy and the American Revolution: a Reappraisal." Naval War College Review 1994 47(4): 83-108. Issn: 0028-1484

- Schaeper, Thomas J. France and America in the Revolutionary Era: The Life of Jacques-Donatien Leray de Chaumont, 1725-1803. Berghahn Books, 1995. 384 pp. He provided military supplies.

- Unger, Harlow Giles. Lafayette (2002)online

The Civilian Founders: biographies

- Brodsky, Alyn. Benjamin Rush: Patriot and Physician. 2004. 404 pp.

- Burnard, Trevor. "The Founding Fathers in Early American Historiography: a View from Abroad." William and Mary Quarterly (2005) 62(4): 745-764. Issn: 0043-5597 Fulltext: in History Cooperative

- Ellis, Joseph. Passionate Sage: The Character and Legacy of John Adams (2001) online edition

- Ellis, Joseph. Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation (2002)

- Irvin, Benjamin H. Sam Adams: Son of Liberty, Father of Revolution. Oxford University Press, 2002. 176pp.

- Ferling, John. John Adams: A Life (1992).

- Ketcham, Ralph L. Benjamin Franklin. (1966). 228pp online edition

- Malone, Dumas. Jefferson and His Time (vol 1-2 1948),

- Peterson, Merrill D. Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography (1970). online edition

- Withey, Lynn. Dearest Friend: A Life of Abigail Adams (1981)

George Washington

- Alden, John. George Washington: A Biography (1984);

- Cunliffe, Marcus. George Washington: Man and Monument (1958), classic short biography

- Ellis, Joseph. His Excellency: George Washington (2005), interpetive essay

- Freeman, Douglas Southall George Washington: A Biography (7 vols., New York, 1948–1957); also one-vol abridged edition

- Lengel, Edward G. General George Washington: A Military Life. Random House, 2005. 450 pp.

Primary sources

- Library of America. The American Revolution: Writings from the War of Independence (1995) 850pp table of contents

- Commager, Henry Steele, and Richard Morris, eds. The Spirit of 'Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants (1967); excellent collection of primary ources; highly recommended

- Morison, S. E. ed. Sources and Documents Illustrating the American Revolution, 1764-1788, and the Formation of the Federal Constitution (1923) online edition

- Lafayette, Marquis de. Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776-1790. Vol. 2: April 10, 1778-March 20, 1780. Cornell U. Press, 1979. 518 pp.

- Kierner, Cynthia A. ed. Southern Women in Revolution, 1776-1800: Personal and Political Narratives, 1998. 253 pp.

- Washington, George. Writings (1988) (Library of America edition) 440 letters and key documents. online table of contents

- Washington, George. The Papers of George Washington: Revolutionary War Series. University Press of Virginia. Latest volume is Vol. 14: March-April 1778. ed by Philander D. Chase, 2004. 832 pp.

- Documents of the American Revolution, 1770-1783 Ed. by K.G. Davies. 21 vols. (Irish Academic University Press, 1972), all the important British documents

External links

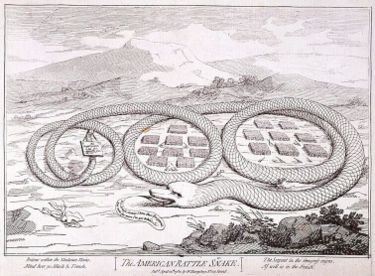

- ↑ James Gillray. "The American Rattle Snake." London: W. Humphrey, April 1782. Etching.