Gaius Iulius Caesar (name): Difference between revisions

imported>Daniel Mietchen |

imported>John Stephenson m (moved Gaius Iulius Caesar (name)/Draft to Gaius Iulius Caesar (name): citable version policy) |

Revision as of 15:10, 22 August 2013

Gaius Iulius Caesar (Greek: ΓAIOΣ IOYΛΙΟΣ KAIΣAΡ[1]) was a prominent name of the gens Iulia since Roman Republican times, borne by a number of figures from history, most notably the dictator Julius Caesar.

Bearers

Republican

- Gaius Iulius Caesar, son of Sextus Iulius Caesar

- Gaius Iulius Caesar, son of the former, father of proconsul Gaius Iulius Caesar, married to Marcia (daughter of consul Quintus Marcius Rex)

- Gaius Iulius Caesar († 85 BC), proconsul, father of the dictator Julius Caesar

- Gaius Iulius Caesar Strabo (Vopiscus) (ca. 130–87 BC), son of Lucius Iulius Caesar and Poppilia

- Gaius Iulius Caesar (100–44 BC), dictator perpetuo, commonly referred to as Julius Caesar

Imperial

- Gaius Iulius Caesar (63 BC – AD 14), the first emperor Augustus, born Gaius Octavius, often referred to by scholars as Octavian for the time until January 16, 27 BC

- Gaius Iulius Caesar (Vipsanianus) (20 BC – AD 4), adopted son of Augustus, commonly referred to as Gaius Caesar

- Gaius (Iulius) Caesar Germanicus (AD 12–41), Roman emperor, commonly referred to as Caligula, seldomly as Gaius

Julius Caesar's name

The name of the dictator Julius Caesar—Latin script: CAIVS IVLIVS CAESAR—was often extended by the official filiation Gai filius ("son of Gaius"), rendered as Gaius Iulius Gai filius Caesar. A longer version can also be found, however rarely: Gaius Iulius Gai(i) filius Gai(i) nepos Caesar ("Gaius Julius Caesar, son of Gaius, grandson of Gaius").[2] Caesar often spoke of himself only as Caius Caesar,[3] omitting the nomen gentile Iulius.[4] After his senatorial consecration as Divus Iulius in 42 BC, the dictator perpetuo bore the posthumous name Imperator Gaius Iulius Caesar Divus (IMP•C•IVLIVS•CAESAR•DIVVS, best translated as "Commander [and] God Gaius Julius Caesar"), which is mostly given as his official historical name.[5] Suetonius also speaks of the additional cognomen Pater Patriae,[6] which would render Caesar's complete name as Imperator Gaius Iulius Caesar Pater Patriae Divus.

The praenomen Gaius

Gaius is an archaic Latin name and one of the earliest Roman praenomina. Before the introduction of the letter G into the Latin alphabet, i.e. before the censorship of Appius Claudius Caecus in 312 BC,[7] the name was only written as Caius. The old spelling remained valid in later times and existed alongside Gaius, especially in the form of the abbreviation C.

The only known original Roman etymology of Gaius is expressed as a gaudio parentum,[8] meaning that the name Gaius stems from the Latin verb gaudere ("to rejoice", "to be glad"). This etymology is commonly seen as incorrect, and the origin of Gaius is often stated as still unknown.[9] Some have linked the name to an unknown Etruscan phrase, others to the gentilician name Gavius, which possibly might have lost the medial v in the course of time.[10] But no supporting evidence has been found to this day.

The most promising explanation can however be found in the folk-etymological derivation from the Greek word γαῖα (gaîa, "earth"), specifically γῆ ("gê") or γᾶ ("gâ"), which is supported by the Roman vow of marriage that the fiancée had to give: Ubi tu Caius et ego Caia. ("Where you [will be], Gaius, likewise I [will be], Gaia.")[11] By the inclusion of Gaius and Gaia in the vow, the two names could of course be identified simply as "man" and "woman". But since the vow was originally an archaic rural ceremony, the vernacular explanation by the Romans, who had always been farmers, will have been "woman of the Earth" and "man of the Earth",[12] referring also to the agricultural property of the family.

The nomen gentile Iulius

Virgil[13] and his commentator Servius[14] wrote that the gens Iulia had received their name Iulius from the family's common ancestor, Aeneas' son Ascanius,[15] who was also known under his cognomen Iulus, which is a derivative of iulus, meaning "wooly worm".[16] Such nicknames were typical for cognomina and were the base of old gentilician names.[17] By tracing their descent from Aeneas, the Iulii belonged to the so-called "Trojan" families of Rome.

Weinstock (1971) made a case for Iullus being a diminutive, i.e. juvenescent theophoric name of Iovis, which used to be one of the older names of the god Iuppiter. Weinstock's argument however relies on a hypothetical intermediate form *Iovilus, and he stated himself that Iullus can't originally have been a theophoric name and could therefore only have become one at a secondary stage, after the Julians had established the identification of Iulus as their gentilician god Vediovis (also: Veiovis), who was a "young Iuppiter" himself.[19] Therefore Alföldi (1975) is correct in rejecting this proposed etymological origin.

Members of the Julian family like their chronicler Lucius Caesar later connected the name Iulus with ἰοβόλος ("the good archer") and ἴουλος ("the youth whose first beard is growing").[20] This has however no etymological value and is only a retrofitting interpretation concernced with the earlier institution of the Vediovis-cult in Rome together with a statue of Iulus-Vediovis as a (possibly bearded) archer.[21] Others derived Iulius from king Ilus, who was the founder of Ilium.[22] Weinstock rightfully called these the "usual playful etymologies of no consequence".[23]

The cognomen Caesar

In earlier times Caesar could originally have been a praenomen.[24] The suffix –ar was highly unusual for the Latin language, which might imply a non-Latin origin of the name. The etymology of the name Caesar is still unknown and was subject to many interpretations even in antiquity.

Folk etymology

Several interpretations were propagated, all of which remain highly doubtful, especially in part due to their derogatory nature:

- a caesiis oculis[25] ("because of the blue eyes"): Caesar's eyes were black,[26] but since the despotic dictator Sulla had had blue eyes, this interpretation might have been created as part of the anti-Caesarian propaganda in order to present Caesar as a tyrant.[27]

- a caeso matris utero[28] ("born by Caesarean section"): In theory this might go back to an unknown Julian ancestor who was born in this way. On the other hand it could also have been part of the anti-Caesarian propaganda, because in the eyes of the Republicans Caesar had defiled the Roman "motherland", which was also reported for one of Caesar's dreams, in which he committed incest with his mother, i.e. the earth.[29]

- a caesaries[30] ("because of the hair"): Since Caesar was balding, this interpretation might have been part of the anti-Caesarian mockery. However, this derisive interpretation shows a resemblance to the possible original etymology of the name (see below), although Festus' etymology suggests that he had no knowledge of any non-Latin origin.

Caesarian and Julian etymology

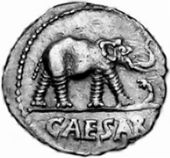

Julius Caesar himself propagated the derivation from the elephant, an animal that was said to have been called caesai in the "Moorish", i.e. probably Punic language,[31] thereby following the claims of his family that they inherited the cognomen from an ancestor, who had received the name after killing an elephant, possibly during the first Punic War. Since the Gauls came to know the elephant through the Punic commander Hannibal, it is possible that the animal was also known under the name caesar or caesai in Gaul. Caesar used the animal during his conquest of Gaul and probably of Britain,[32] which is further supported by the inclusion of forty elephants on the first day of Caesar's Gallic triumph in Rome.[33] Caesar displayed an elephant above the name CAESAR on his first denarius, which he probably had minted while still in Gallia Cisalpina. Apart from using the elephant as a claim for extraordinary political power in Rome,[34] the coin is an unmasked allusion to this etymology of the name and directly identifies Caesar with the elephant, because the animal treads a Gallic serpent-horn, the carnyx, as a symbolic depiction of Caesar's own victory.[35]

An alternative interpretation of Caesar deriving from the verb caedere ("to cut"; see above) could theoretically have originated in the argument of the Julians for receiving a sodality of the Lupercalia, the luperci Iulii (or Iuliani). Since the praenomen Kaeso (or Caeso) was at first a proprietary name of the Quinctii and the Fabii, possibly derived from their ritual duty of striking with the goat-skin (februis caedere) at the luperci Quinctiales and the luperci Fabiani respectively, the Julians would then have argued that the name Caesar was identical to the Quinctian and Fabian Kaeso.[36] The identification of the cognomina Kaeso and Caesar was indeed supposed by Pliny, but is—according to Alföldi (1975)—unwarranted.[37]

C·AESAR and the Etruscan 𐌛𐌄𐌔𐌉𐌀

to be added later

Sabine origin of caesar: a possible "true etymology"

to be added later

Notes

- ↑ Γάιος Ιούλιος Καίσαρ (Gáios Ioúlios Kaísar)

- ↑ The occurrence of the double i, as e.g. in Iulii or Gaii, was customary for Latin writings after the end of the Republic. The single i (Iuli, Gai etc.) is Republican Latin.

- ↑ Caius is the old-Latin variant of Gaius (see also below).

- ↑ Plutarchus, Caesar 46; Suetonius, Divus Iulius 30

- ↑ Augustus' would eventually follow the use of Imperator as a praenomen. For Caesar's precedent see Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, Divus Iulius 76: since Imperator here is a true praenomen, a translation ("commander") should—if at all—only be given for explanatory purposes. The same would apply for Divus ("god"), which derived from Caesar's god name Divus Iulius (at the latest since early 44 BC), and is therefore (as part of his name) per se untranslatable.

- ↑ Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, Divus Iulius 76; the neuter variant Parens Patriae is also known from a statue of Caesar in Rome.

- ↑ RE XVI 1661

- ↑ Auct. de praen. 5: Gai iudicantur dicti a gaudio parentum; quoted in Paulus Diaconus, abridged summary of Sextus Pompeius Festus, De Verborum Significatu

- ↑ Cp. e.g. RE XVI 1668, pp. 14 sqq.; Frederic D. Allen, "Gajus or Gaius?", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, Vol. 2, 1891, pp. 71–87

- ↑ Proposed e.g. by George Davis Chase, "The Origin of Roman Praenomina", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, Vol. 8, 1897, pp. 103–184

- ↑ Plutarch, Roman Questions 30; Plutarch himself is unsure of the meaning and the right translation, giving possible connections to the couple's heirship and houshold or to Gaia Caecilia, spouse of king Lucius Tarquinius Priscus.

- ↑ In Greek, Gaius is rendered as Gaios, which mirrors the geographical γαιήϊος (gaiêios, "born from the earth"); cp. also Homer, Odyssey 7.24.

- ↑ Publius Vergilius Maro, Aeneid 1.272 & 6.756

- ↑ Maurus Servius Honoratus, Commentary on the Aeneid of Vergil 1.267

- ↑ Sextus Pompeius Festus, De verborum significatu 340 M. (460 L.); RE 10.106 & 953

- ↑ Later used by Pliny for the wooly part of a plant; early form: Iullus

- ↑ E.g. claudus ("lame", "crippled") for Claudius, Petro ("bumpkin", "fool") for Petronius etc.

- ↑ The coin shows the Julian gentilician god Vediovis identified as Apollo and also bearing attributes of Iuppiter, i.e. the thunderbolt beneath the head.

- ↑ Verrius Flaccus: Paul. 379 M. (519 L.); Ovid F. 3.437 (on Veiovis on the Capitol). Aeneas had been divinized as Iuppiter indiges, which supported the identification of Aeneas' son Iulus as the "young Iuppiter" Vediovis, especially since Iulus had inaugurated Aeneas' cult and had built him a temple in Alba Longa.

- ↑ Servius, Commentary on the Aeneid 1.267.

- ↑ Cf. the identification of Vediovis with Iuppiter and Apollo (see above; Rev. Num. 1971; Chiron 2, 1972; Sydenham 76 et al.).

- ↑ Verg. Aen. 1.267, in: Servius (and Dan.) Commentary on the Aeneid 1.267.

- ↑ "Divus Julius", Oxford 1971, p. 9.

- ↑ Auct. de praen. 3. Quoted in Stefan Weinstock: Divus Julius (Oxford 1971/2004).

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Aelius 2.3

- ↑ Suetonius, Divus Iulius 45

- ↑ Ludwig von Doederlein also proposed an origin from caesius, but rather interpreted it as "grey" and applied it to the color of the skin or perhaps of the eyes (Synon. III 17, mentioned in "Caesar", in Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898).

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History 7.7

- ↑ Suetonius, Divus Iulius 7; Cassius Dio 37.52.2

- ↑ According to Sextus Pompeius Festus.

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Aelius 2.3; Servius, Commentary on the Aeneid 1.286 i.a.; cp. Pauly-Wissowa RE X 464 sq.

- ↑ Polyaenus (Stratagems 8:23.5) tells the story about Caesar using an armoured elephant during his expeditions at the river Thames.

- ↑ Suetonius, Divus Iulius 37.2. In addition Cassius Dio (43.22.1) mentions elephants as part of Caesar's entourage after a banquet in Rome on the fourth day of the same triumph.

- ↑ Artemidorus established that the elephant, undoubtedly a symbol of honor (and arrogance), denoted a δεσποτης ("lord"), a βασιλευς ("imperator [of Rome]"; "king [in Greece]) or a και ανηρ μεγιστος ("man in high authority") on the Italian mainland. Therefore the coin would have to be seen as a presage for Caesar's future dominion. (From Stevenson et al.: A Dictionary of Roman Coins: Republican and Imperial. London 1889.)

- ↑ Cf. Christoph Battenberg, Pompeius und Caesar: Persönlichkeit und Programm in ihrer Münzpropaganda, Marburg/Lahn 1980. Furthermore the elephant was a counter-symbol against the gens Caecilia, whose heralding symbol was the elephant, attesting victories gained by the Metelli in Sicily (250 BC) and Macedonia (148 BC). In 49 BC Metellus Scipio had ordered Caesar to surrender his army, although Pompeius was levying troops, and the Metelli had also tried to stop Caesar from confiscating the state treasury in the temple of Saturn, where Caesar eventually had his coins struck. Therefore Caesar's propaganda communicated not only the taking of the treasure but also the taking of his enemies' symbol and placed his own victory over Gaul above the Metellan victories.

- ↑ A later Republican inscription mentions a member of the Julian family named K(AESO) IVLIVS (CIL 12.2806).

- ↑ Andreas Alföldi: "Review of St. Weinstock, Divus Julius". In: Gnomon 47 (1975). 154–179.

?

I don't seem to be able to get into either talk page, so I'll have to comment here.

The text above refers to the censorship of Claudius in 312 BC. My understanding is that chronology before 300 BC isn't precise to the nearest year. Is that right? Peter Jackson 16:46, 24 November 2008 (UTC)