Crystal Palace/Citable Version: Difference between revisions

imported>Chris Day (rigeur to rigueur) |

imported>John Stephenson m (moved Crystal Palace to Crystal Palace/Citable Version: citable version policy) |

Revision as of 16:45, 25 August 2013

The Crystal Palace was a glass and iron structure built to house the Great Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in Hyde Park, London, in 1851. After the Exhibition, it was moved and expanded and rebuilt on Sydenham Hill overlooking London, where it enjoyed a second life from 1854 until a horrific fire destroyed it in 1936.

The Crystal Palace is a significant structure in many ways: it was the first structure of its size assembled from prefabricated parts; its system of horizontal trusses has since become one of the most widely-used construction methods in the world; it was at the time the world's largest enclosed open-air structure; and its success inspired the building of similar structures around the world, from the New York Crystal Palace in New York City to the Kibble Palace in Glasgow. It also symbolizes technological prowess and imperial power of enormous historical and cultural significance. In its second incarnation in Sydenham as a suburban pleasure palace it drew crowds away from the central metropolis and was also a concert hall, famous for its performances of Handel with a massed orchestra, choir, and the Palace's enormous organ; a recording of such a performance in 1888 is the earliest known recording of live music in existence. Its exterior park, with fountains, terraces, and an outdoor exhibition of life-size dinosaur sculptures, was also highly influential. It also housed, from 1933 to 1936, the experimental studios of the Baird television company, which made regular short-wave broadcasts from its South Tower.

Planning and construction

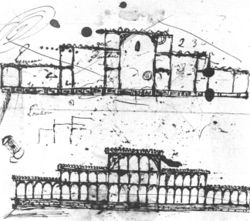

The Commissioners originally envisioned the building that would house the Great Exhibition as a substantial, permanent structure of brick and stone, and the initial proposals reflected this. However, with the choice of Hyde Park for the exhibition's site, many were concerned about the impact of such a large, fixed structure on the park's open areas, which defenders hailed as one of the "lungs of the metropolis." Sir Joseph Paxton then informally approached one of the commissioners, sketching out a rough elevation (shown at left) of a multi-story glass structure, with cast iron uprights and supports. He claimed it could be speedily built, incorporate existing trees inside its structure, and be removed afterward, thus preserving Hyde Park as a green space. Although encouraged that it was not too late to submit his alternative plans, Paxton had just nine days to submit his final bid. So he called upon the Messrs Fox and Henderson, the only firm he knew capable of manufacturing and installing such an enormous amount of glass, and their detailed proposal cost £150,000. However, since the building materials could be taken down and re-used, the firm offered to undertake the job for only £79,800, a mere fraction of the amount contemplated under the plan for a permanent structure.

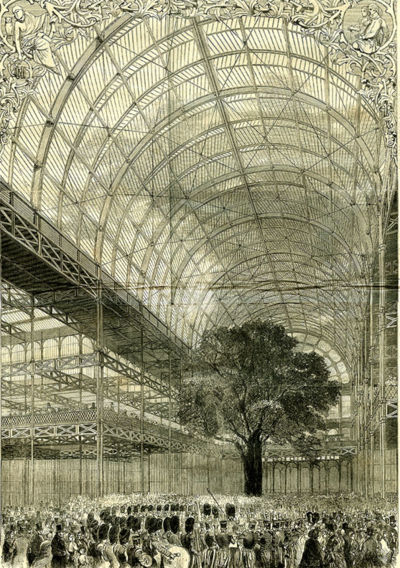

With Paxton's proposal in hand, the commissioners laid out a remarkable new set of criteria, including a much-reduced budget and a requirement that any structure built be dismantled when the the Exhibition concluded. Paxton's proposal, as the commissioners well knew, was now the only one meeting the new standards, so it was speedily approved. Some criticized the choice, as Paxton had only previously built greenhouses for the gardens of nobility, none of which had been nearly as large as the proposed structure. Colonel Sibthorp, a conservative MP with a history of bees in his bonnet, took up the charge against the plan, complaining that the trees would be suffocated, the grass killed off, and helpless exhibition-goers cut to ribbons by falling glass. Sibthorp's criticisms failed to derail the commissioners, however, and the builder's speed and skill spurred popular support. In the end, when Queen Victoria and Prince Albert arrived for the grand opening of the building, the beauty, practicality, and strength of Paxton's designs were immediately evident, and the building was hailed as a new wonder of the world. William Makepeace Thackeray, writing for Punch, dubbed the building a "Crystal Palace," and it was known by that name for the rest of its existence.

The Great Exhibition

The preparations for the Great Exhibition were considerable. In addition to the construction itself—which involved some 900,000 square feet of glass, and the decorative color-scheme that required the labor of 500 painters—the interior of the building was enormous. With 11 miles of stalls and over 100,000 individual exhibits, assembling the interior required the constant labor of 2,000 men for three months. With exhibits ranging from the gargantuan (entire railway-engines and enormous pistons) to the mundane (galleries filled with linen cloth, patented invalid chairs, and galvanized walking-sticks), the sheer size and variety of material was an attraction in itself. And yet, until the opening day, the public had to be content to see hundreds of "Pickford's Vans" (horse-drawn moving carts of the day) admitted daily to the sanctuary, screened from view by vast wooden hoardings.

On May 1, 1851, together with Prince Albert, Queen Victoria officially opened the Exhibition at the Palace. The massive and ornate opening ceremonies included a procession with the Royal Family, leading military officials, and the Duke of Wellington. Thirty thousand ticketed guests filled the Palace to capacity while half a million others stood outside in the park. The Queen and the Prince Consort ascended to a specially-built, velvet-draped dais in the central transept, and stood while the great organ played "God Save the Queen." The Prince read briefly from the Commissioners' report for the Exhibition, and the Archbishop of Canterbury offered a prayer. The emotion which attended the event is palpable in the account of the Times of London:

- "There was today witnessed a sight the like of which has never happened before and which in the nature of things cannot be repeated. They who were so fortunate as to see it hardly knew what most to admire, or in what form to clothe the sense of wonder and even of mystery which struggled within them. The edifice, the treasures of art collected therein, the assemblage, and the solemnity of the occasion, all conspired to suggest something more than sense could scan, or imagination attain."

Move to Sydenham

Despite a number of proposals to retain the Crystal Palace at the Hyde Park site, perhaps as a "Winter Garden," the Commissioners remained firm, and Fox and Henderson were eager to reclaim the raw materials. And, despite its enormous success; there was a sense that it was time for the Palace to go; as Henry Morley wrote in Dickens's magazine Household Words:

- "The success of the Exhibition has been perfect. It is the grandest feature of the age in which we live. It is the property of 1851, and must be history to 1852. It must go, and we wish it to go,–its part will have been played, and it must not remain superfluous upon the stage."[1]

Yet even though the materials were valuable, their primary value lay in their ability to be re-assembled. The cost of such an operation persuaded a number of people that a new, permanent site, and an expanded Palace, would be best envisioned as a private undertaking. The Crystal Palace Company was therefore formed with Paxton as its chairman, and £500,000 in private capital was raised. A site was found in Penge, Sydenham, atop a large hill which had been part of Penge Park. In Roman times, the hill had been a site for bonfire beacons to warn Londoners of peril; now it would be a beacon of "crystal light," a radiant city on a hill accessible to Londoners in search of an escape from their grimy metropolis.

Paxton's new plans called for a structure more than half again as large as the original, and nearly twice as high. The new Palace was to have five rather than three stories, and in addition to its now-enormous central transept, it required two lesser transepts, one at either end, to balance out the design. The area of glass required was now 1,650,000 square feet, such that the glass from the original palace filled less than two-thirds of the need. Inevitably, such ambition overreached the estimated cost, and the half-million pounds was quickly exhausted. Additional shares were easy to come by, however, and assured that the result would be a success. The company raised a further £800,000 to complete the Palace, landscape its grounds, and install an enormous system of fountains and water-works (the two towers were added to provide space for the water-tanks). Construction began in 1853 and was completed in 1854; everything went smoothly, with one dramatic exception, an accident in which the scaffolding for one of the massive arches in the central transept collapsed, killing twelve men. The Palace was re-opened and re-dedicated in 1854, again with Queen Victoria performing the honors, and again with still a larger orchestra, a larger pipe organ, and the largest mass chorus ever yet assembled in Britain. Some landmarks of the old Palace, such as Osler's Crystal Fountain, remained, but whole new galleries of art -- much of it plaster casts of sculpture from around the world -- beckoned the curious. At one end, a nearly full-size replica of the statues of Abu Simbel was erected to oversee the "Egyptian Court," while other dining and shopping areas, based on the original Palace, such as Pugin's Medieval Court, were located throughout the building.

Concerts and fireworks

For its first two decades, the Crystal Palace was a tremendous success as a holiday destination, but only a modest financial success. The great cost of upkeep of its grounds, fountains, and interior spaces was never quite covered by ticket receipts, and as time wore on, both patrons and exhibitors were inclined to want to pay a bit less for their privileges. A dedicated railway line to the Palace proved a success, and was connected to the main building by a cloister-like underground passageway, whose vaulted ceilings survive to this day. Thursday evenings at the Palace quickly became de rigueur for Londoners, who took in the park and grounds and then settled in on the enormous terraces for an evening of Mr. Brock's fireworks displays, which featured gigantic set-pieces depicting patriotic scenes, such as St. George slaying the dragon. Balloon ascents, and even races, were another popular fixture.

The Palace suffered a fire in 1867, ironically just two days before a certain Rev. H.M. Hart was to lecture on "Fire, what causes it, and how it is extinguished," which nearly destroyed the North Transept. The Alhambra Court, the Assyrian Court, and the entire department of tropical plants were all destroyed, as were the replica figures of Abu Simbel. It required two years to rebuild that end of the Palace, but due to the cost, the transept was not rebuilt, but simply finished off at the same elevation as the rest of the building.

Later years

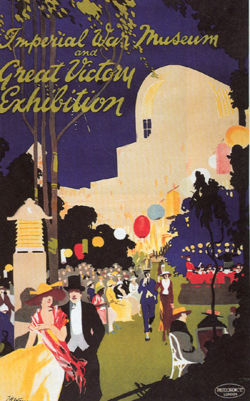

As the nineteenth century wore on, the financial health of the Company grew ever weaker. Everything that attracted people to the park was expensive, but fees could never recover the entire expense. The Company survived by selling off tracts of parkland to local developers for housing estates, but by 1911 their situation was dire. They declared bankruptcy, and the property might have been auctioned off had it not been saved at the last minute by Lord Plymouth, who purchased it in order to "save it for the people." Lord Plymouth's generosity stirred public support, and s a subscription was taken up to reimburse him for his kindness; with these funds it was then re-purchased in 1912, becoming the "property of the Nation." Unfortunately, the Nation was just then in the midst of a war, and the Palace was requisitioned as a naval barracks, dubbed "HMS Victory IV" by its denizens. For a time, it served as a temporary warehouse for the Imperial War Museum, but the poor condition of the building cried out for greater renovation. In 1920, Sir Henry Buckland began his efforts to repair and upgrade the Palace; he renovated the interior and repaired the long-dry fountains. Among his tasks was locating tenants for the largely empty structure, and in this he enjoyed at least a modest success.

Final decade and destruction

By the late 1920s, the Palace was at least somewhat back on its feet. Patrick Beaver, author of a well-respected book on the Palace, describes his schoolboy visits during this time:

- "On afternoons during the school holidays, and always on a Thursday so as not to miss the fireworks, a schoolfriend and I used to visit the Crystal Palace, arriving early in the morning and leaving when it closed at about 10 p.m.. For the best part of the day we usually had the entire forty-four million cubic feet to ourselves . . . I remember the echo of our footsteps and voices in the great emptiness of the nave . . . the souvenir stands had gone long ago and the bars and refreshment rooms were always closed.[2]

On the evening of November 30th, 1936, Sir Henry Buckland, alerted by a neighbor, ran out of his nearby home to see an ominous glow rising from the Palace's central nave. He at once summoned the local fire brigade, and sent a man up the hill to tell the members of an orchestra, who he knew were having a late rehearsal, that there was no immediate danger. On his return, the man told Sir Henry that the musicians had fled, and the concert rooms were already afire. The Palace was doomed, and rather like Thomas Andrews aboard the Titanic, Sir Henry knew it. Nevertheless, if anything could be done, he felt he must do it. The Penge Fire Brigade were the first to arrive, and quickly realized that the fire far exceeded their resources to contain. Eventually 389 firefighters and 89 engines would be summoned, but there was little they could do other than to prevent the spread of the fire to adjoining buildings.

As described by an eyewitness, the sight of the end of the Palace was quite as moving, though in an opposite fashion, as had been its opening by Queen Victoria eighty-two years previous:

- "Great crashes and explosions could be heard, and billowing mountains of spark-filled clouds, about twice the height of the 350-ft. towers, rolled away over South Kent, flaming with the glow of the fire . . . when we got to the Crystal Palace parade at the top of the hill, we found a seething mass of people -- cars, bicycles, and pedestrians -- and still more thousands streaming up from every hill and road. Fire-engines trying to run out their hoses; cars and bicycles and humans rushing over the hoses -- and over and above all the blinding blaze of the C.P. alight almost from end to end."[3]

The fire burned most of the night, melting the glass panels and softening the steel superstructure such that, one by one, the great supporting arches twisted and fell. By morning, nothing was left but a tangled ruin. The fire's cause was never clearly determined, though it appears a forgotten cigarette in a ladies' washroom may have ignited the flooring, and the fire spread through the space between the joists. Surveying the ruins the next morning, Sir Winston Churchill pronounced it the "end of an era."

The Palace site today

In the wake of the fire, most of the remaining metalwork was removed and sold for scrap, and what could not be salvaged was plowed under, filling in what had been the basement level of the palace. The two towers were eventually demolished, in part because during World War II there was a concern that they could be used as a landmark by German bombers. The only remaining usable structure is the old foundation of the South Tower, which serves as a small museum, open only on Sundays and Bank Holidays. The terraces themselves remain, but in a partly crumbling condition, with orange plastic safety fencing restricting access to some areas. After a proposed shopping center for the site was eventually defeated by the hard work of the Crystal Palace Campaign, future plans for the site are uncertain. A proposal to re-build the Palace instead of building the Greenwich Dome to celebrate the millennium was, to the regret of some, never considered. A large radio antenna tower now dominates the hilltop site, and the portrait bust of Sir Joseph Paxton now looks out over the weed-overgrown area where the palace once stood.

Much of the area of the original palace grounds remains as parkland, administered by the London Borough of Bromley, though additional slivers of land have been sold off over the years. The dinosaurs, long in a very dilapidated state, were restored to like-new condition in 2001-2002 with the help of National Lottery funds. The original hedgerow Maze still stands atop its mound, one of the few remaining features of the park's early landscaping.

To the east of the Palace site is an area set aside for sport. There is a long history of football at the site. In 1861, the original team comprised of players that were groundkeepers for the Great Exhibition and nicknamed the "Glaziers," due to the immense amount of glass once used in the Palace. The team was one of the eleven founding members of the Football Association and reached the semi-final stage of the first FA Cup competition. From 1895 to 1914, the FA Cup finals were held at the Crystal Palace as well as being a venue for the England national team. The first football club was succeeded by a second team of the same name in 1905. From 1905 to 1915, the football stadium was the home to the Crystal Palace Football Club until they were relocated due to the Admiralty requisitioning the Crystal Palace; they eventually settled at nearby Selhurst Park, in 1924. It was also a venue for motorcycle and car racing and is currently the home for the National Sports Centre, built on the site of an earlier football stadium. The sports center is currently undergoing renovations, including the removal of its oversize turnstile gates, which had become an eyesore.

Cultural significance

Even immediately after its destruction, the cultural significance of the Palace was evident. Sir David Low, the eminent British cartoonist, remarked on the great public displays of affection for the Palace in the week after its destruction; the outpouring had been so impressive, he quipped, that "plans are underway to burn down the Albert Memorial." The Palace has since been hailed both as a symbol of the imperial glory of the British Empire and a sign of its inexorable decline. In his book, All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity, Marshall Berman takes the burning of the Palace in 1936 as a landmark of modernity and a harbinger of postmodernity to come.

References

- ↑ Henry Morley, "What is Not Clear about the Crystal Palace, Household Words, July 12th 1851.

- ↑ Patrick Beaver, The Crystal Palace: 1851-1936 (London: Hugh Evelyn Ltd., 1970) p. 136.

- ↑ Letter from Edgar McWilliam, December 1st, 1936, personal collection of Russell A. Potter, retrieved from [1]