User:Milton Beychok/Sandbox: Difference between revisions

imported>Milton Beychok |

imported>Milton Beychok |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

The first commercial LNG liquefaction plant was built in [[Cleveland, Ohio]], in 1941 and the LNG was stored in tanks at atmospheric pressure, which raised the possibility that LNG could be transported in sea-going vessels. In January 1959, the world's first LNG carrier, a converted freighter named ''The Methane Pioneer'', containing five small, insulated aluminum tanks transported 5,000 m<sup>3</sup> (about 2,250 metric tons) of LNG from [[Lake Charles, Louisiana]] in the [[United States]] to [[Canvey Island]] in [[England]]'s [[Thames river]]. That voyage demonstrated that LNG could be transported safely across the oceans. During the next 14 months, that same freighter delivered seven additional cargoes with only a few small problems.<ref name=CEE/><ref name=Nontech>{{cite book|author= Michael R. Tusiani and Gordon Shearer|title=LNG: A Nontechnical Guide| publisher-Pennwell Corp.|year=2007|pages= p.138|id=ISBN 0-87814-885-X}}</ref> | The first commercial LNG liquefaction plant was built in [[Cleveland, Ohio]], in 1941 and the LNG was stored in tanks at atmospheric pressure, which raised the possibility that LNG could be transported in sea-going vessels. In January 1959, the world's first LNG carrier, a converted freighter named ''The Methane Pioneer'', containing five small, insulated aluminum tanks transported 5,000 m<sup>3</sup> (about 2,250 metric tons) of LNG from [[Lake Charles, Louisiana]] in the [[United States]] to [[Canvey Island]] in [[England]]'s [[Thames river]]. That voyage demonstrated that LNG could be transported safely across the oceans. During the next 14 months, that same freighter delivered seven additional cargoes with only a few small problems.<ref name=CEE/><ref name=Nontech>{{cite book|author= Michael R. Tusiani and Gordon Shearer|title=LNG: A Nontechnical Guide| publisher-Pennwell Corp.|year=2007|pages= p.138|id=ISBN 0-87814-885-X}}</ref> | ||

The demonstrated ability to transport LNG in sea-going vessels spurred the building of large-scale LNG liquefaction plants at major gas fields world-wide. The first large-scale LNG plant began operating in 1964 at [[Arzew, Algeria]] and initially produced about 2,360 metric tons/day (MT/day) of LNG. In 1969, another LNG plant began operating near [[Kenai, Alaska]] and initially produced LNG at a rate of about 3,400 MT/day.<ref name=CEE/><ref name=Charter>[http://www.encharter.org/fileadmin/user_upload/document/LNG_2008_ENG.pdf Fostering LNG Trade: Role of the Energy Charter] 2008, Appendices A and C, from the website of the Energy Charter Secretariat.</ref> | |||

By mid-2008, there were 19 LNG liquefaction plants operating in 15 countries worldwide. There were also 65 LNG receiving terminals (often referred to regasification terminals) operating in 19 countries world-wide. | |||

{{TOC|right}} | |||

'''Liquefied natural gas''' or '''LNG''' is [[natural gas]] (predominantly [[methane]], CH<sub>4</sub>) that has been converted into liquid form for ease of transport and storage. More simply put, it is the liquid form of the natural gas that people use in their homes for cooking and for heating, | |||

A typical raw natural gas contains only about 80% methane and a number of higher boiling [[hydrocarbons]] as well as a number of impurities. Before it is liquefied, it is typically purified so as to remove the higher-boiling hydrocarbons and the impurities. The resultant liquefied natural gas contains about 95% or more methane and it is a | |||

clear, colorless and essentially odorless liquid which is neither corrosive nor toxic.<ref name=CalifEnergyCommission>[http://www.energy,ca.gov./faq.html Frequently Asked Questions About LNG] From the website of the [[California Energy Commission]]</ref><ref name=CEE>[http://www.beg.utexas.edu/energyecon/lng/LNG_introduction.php Introduction To LNG] Michelle Michot Foss (January 2007), Center for Energy Economics (CEE), Bureau of Economic Geology, Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas</ref> | |||

LNG occupies only a very small fraction (1/600th) of the volume of natural gas and is therefore more economical to transport across large distances. It can also be stored in large quantities that would be impractical for storage as a gas.<ref name=CalifEnergyCommission>[http://www.energy,ca.gov./faq.html Frequently Asked Questions About LNG] From the website of the [[California Energy Commission]]</ref><ref name=CEE>[http://www.beg.utexas.edu/energyecon/lng/LNG_introduction.php Introduction To LNG] Michelle Michot Foss (January 2007), Center for Energy Economics (CEE), Bureau of Economic Geology, Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas</ref> | |||

==Process description for the production of LNG== | |||

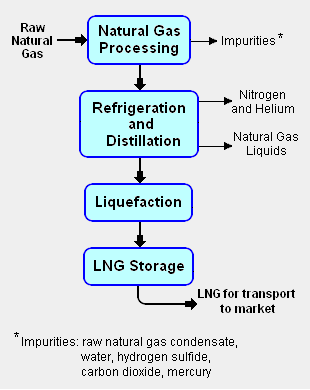

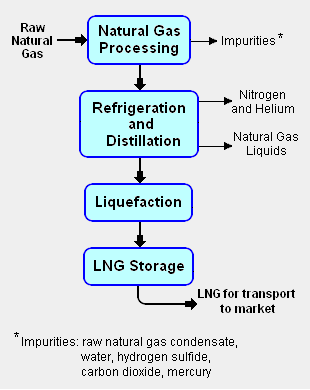

{{Image|LNG block flow diagram.png|right|310px|Fig.1: Block flow diagram of the LNG liquefaction process. See [[Natural gas processing]] for more details.}} | |||

The liquefaction process involves separating the raw natural gas from any associated water and high-boiling hydrocarbon liquids (referred to as [[natural gas condensate]]) that may be associated with the raw gas. The raw gas is then further purified in a [[natural gas processing]] plant to remove remove impurities such as the [[acid gas]]es hydrogen sulfide (H<sub>2</sub>S) and carbon dioxide (CO<sub>2</sub>), any residual water liquid or vapor, [[mercury]], [[nitrogen]] and [[helium]] which could cause difficulty downstream. ( See the block flow diagram of the liquefaction process in Fig.1) | |||

The purified natural gas is next refrigerated and distilled to recover ethane (C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>6</sub>), propane (C<sub>3</sub>H<sub>8</sub>), butanes (C<sub>4</sub>H<sub>10</sub>) and any higher boiling hydrocarbons, collectively referred to as natural gas liquids (NGL). The natural gas is then [[condensation|condensed]] into a liquid at essentially [[atmospheric pressure]] by using further refrigeration to cool it to approximately -162 °C (260 °F). | |||

As mentioned above, the reduction in volume makes LNG much more cost efficient to transport over long distances where [[pipeline]]s do not exist. Where transporting natural gas by pipelines is not possible or economical, it can be transported by specially designed [[Cryogenics|cryogenic]] sea-going vessels called [[LNG carrier]]s or by either cryogenic rail or road tankers. | |||

==History== | |||

Natural gas liquefaction dates back to the 1820s when [[Great Britain|British]] physicist [[Michael Faraday]] experimented with liquefying different types of gases. [[Germany|German]] engineer [[Carl Von Linde]] built the first practical [[vapor-compression refrigeration]] system in the 1870s. | |||

The first commercial LNG liquefaction plant was built in [[Cleveland, Ohio]], in 1941 and the LNG was stored in tanks at atmospheric pressure, which raised the possibility that LNG could be transported in sea-going vessels. In January 1959, the world's first LNG carrier, a converted freighter named ''The Methane Pioneer'', containing five small, insulated aluminum tanks transported 5,000 m<sup>3</sup> (about 2,250 metric tons<ref>'''Note:'''1 metric ton = 1 tonne = 1,000 kg = 2,204.6 pounds = 1.1023 short tons</ref>) of LNG from [[Lake Charles, Louisiana]] in the [[United States]] to [[Canvey Island]] in [[England]]'s [[Thames river]]. That voyage demonstrated that LNG could be transported safely across the oceans. During the next 14 months, that same freighter delivered seven additional cargoes with only a few small problems.<ref name=CEE/><ref name=Nontech>{{cite book|author= Michael R. Tusiani and Gordon Shearer|title=LNG: A Nontechnical Guide| publisher-Pennwell Corp.|year=2007|pages= p.138|id=ISBN 0-87814-885-X}}</ref> | |||

The demonstrated ability to transport LNG in sea-going vessels spurred the building of large-scale LNG liquefaction plants at major gas fields world-wide. The first large-scale LNG plant began operating in 1964 at [[Arzew, Algeria]] and initially produced about 2,360 metric tons/day (MT/day) of LNG. In 1969, another LNG plant began operating near [[Kenai, Alaska]] and initially produced LNG at a rate of about 3,400 MT/day.<ref name=CEE/><ref name=Charter>[http://www.encharter.org/fileadmin/user_upload/document/LNG_2008_ENG.pdf Fostering LNG Trade: Role of the Energy Charter] 2008, Appendices A and C, from the website of the Energy Charter Secretariat.</ref> | The demonstrated ability to transport LNG in sea-going vessels spurred the building of large-scale LNG liquefaction plants at major gas fields world-wide. The first large-scale LNG plant began operating in 1964 at [[Arzew, Algeria]] and initially produced about 2,360 metric tons/day (MT/day) of LNG. In 1969, another LNG plant began operating near [[Kenai, Alaska]] and initially produced LNG at a rate of about 3,400 MT/day.<ref name=CEE/><ref name=Charter>[http://www.encharter.org/fileadmin/user_upload/document/LNG_2008_ENG.pdf Fostering LNG Trade: Role of the Energy Charter] 2008, Appendices A and C, from the website of the Energy Charter Secretariat.</ref> | ||

| Line 83: | Line 110: | ||

the destination port with the same quantities as were loaded at the liquefaction plant. The | the destination port with the same quantities as were loaded at the liquefaction plant. The | ||

accepted maximum figure for boil off is about 0.15% of cargo volume a day. | accepted maximum figure for boil off is about 0.15% of cargo volume a day. | ||

==LNG Terminals== | |||

{{Image|LNG Terminal.jpg|right|325px|LNG storage tanks in LNG terminal at Yokohama, Japan.}} | |||

==Some Statistics== | |||

==Conversion data== | |||

==References== | |||

{{reflist}} | |||

==LNG Terminals== | ==LNG Terminals== | ||

Revision as of 14:59, 20 February 2011

Liquefied natural gas or LNG is natural gas (predominantly methane, CH4) that has been converted into liquid form for ease of transport and storage. More simply put, it is the liquid form of the natural gas that people use in their homes for cooking and for heating,

A typical raw natural gas contains only about 80% methane and a number of higher boiling hydrocarbons as well as a number of impurities. Before it is liquefied, it is typically purified so as to remove the higher-boiling hydrocarbons and the impurities. The resultant liquefied natural gas contains about 95% or more methane and it is a clear, colorless and essentially odorless liquid which is neither corrosive nor toxic.[1][2]

LNG occupies only a very small fraction (1/600th) of the volume of natural gas and is therefore more economical to transport across large distances. It can also be stored in large quantities that would be impractical for storage as a gas.[1][2]

Process description for the production of LNG

Fig.1: Block flow diagram of the LNG liquefaction process. See Natural gas processing for more details.

The liquefaction process involves separating the raw natural gas from any associated water and high-boiling hydrocarbon liquids (referred to as natural gas condensate) that may be associated with the raw gas. The raw gas is then further purified in a natural gas processing plant to remove remove impurities such as the acid gases hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and carbon dioxide (CO2), any residual water liquid or vapor, mercury, nitrogen and helium which could cause difficulty downstream. ( See the block flow diagram of the liquefaction process in Fig.1)

The purified natural gas is next refrigerated and distilled to recover ethane (C2H6), propane (C3H8), butanes (C4H10) and any higher boiling hydrocarbons, collectively referred to as natural gas liquids (NGL). The natural gas is then condensed into a liquid at essentially atmospheric pressure by using further refrigeration to cool it to approximately -162 °C (260 °F).

As mentioned above, the reduction in volume makes LNG much more cost efficient to transport over long distances where pipelines do not exist. Where transporting natural gas by pipelines is not possible or economical, it can be transported by specially designed cryogenic sea-going vessels called LNG carriers or by either cryogenic rail or road tankers.

History

Natural gas liquefaction dates back to the 1820s when British physicist Michael Faraday experimented with liquefying different types of gases. German engineer Carl Von Linde built the first practical vapor-compression refrigeration system in the 1870s.

The first commercial LNG liquefaction plant was built in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1941 and the LNG was stored in tanks at atmospheric pressure, which raised the possibility that LNG could be transported in sea-going vessels. In January 1959, the world's first LNG carrier, a converted freighter named The Methane Pioneer, containing five small, insulated aluminum tanks transported 5,000 m3 (about 2,250 metric tons) of LNG from Lake Charles, Louisiana in the United States to Canvey Island in England's Thames river. That voyage demonstrated that LNG could be transported safely across the oceans. During the next 14 months, that same freighter delivered seven additional cargoes with only a few small problems.[2][3]

The demonstrated ability to transport LNG in sea-going vessels spurred the building of large-scale LNG liquefaction plants at major gas fields world-wide. The first large-scale LNG plant began operating in 1964 at Arzew, Algeria and initially produced about 2,360 metric tons/day (MT/day) of LNG. In 1969, another LNG plant began operating near Kenai, Alaska and initially produced LNG at a rate of about 3,400 MT/day.[2][4]

By mid-2008, there were 19 LNG liquefaction plants operating in 15 countries worldwide. There were also 65 LNG receiving terminals (often referred to regasification terminals) operating in 19 countries world-wide.

Liquefied natural gas or LNG is natural gas (predominantly methane, CH4) that has been converted into liquid form for ease of transport and storage. More simply put, it is the liquid form of the natural gas that people use in their homes for cooking and for heating,

A typical raw natural gas contains only about 80% methane and a number of higher boiling hydrocarbons as well as a number of impurities. Before it is liquefied, it is typically purified so as to remove the higher-boiling hydrocarbons and the impurities. The resultant liquefied natural gas contains about 95% or more methane and it is a clear, colorless and essentially odorless liquid which is neither corrosive nor toxic.[1][2]

LNG occupies only a very small fraction (1/600th) of the volume of natural gas and is therefore more economical to transport across large distances. It can also be stored in large quantities that would be impractical for storage as a gas.[1][2]

Process description for the production of LNG

Fig.1: Block flow diagram of the LNG liquefaction process. See Natural gas processing for more details.

The liquefaction process involves separating the raw natural gas from any associated water and high-boiling hydrocarbon liquids (referred to as natural gas condensate) that may be associated with the raw gas. The raw gas is then further purified in a natural gas processing plant to remove remove impurities such as the acid gases hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and carbon dioxide (CO2), any residual water liquid or vapor, mercury, nitrogen and helium which could cause difficulty downstream. ( See the block flow diagram of the liquefaction process in Fig.1)

The purified natural gas is next refrigerated and distilled to recover ethane (C2H6), propane (C3H8), butanes (C4H10) and any higher boiling hydrocarbons, collectively referred to as natural gas liquids (NGL). The natural gas is then condensed into a liquid at essentially atmospheric pressure by using further refrigeration to cool it to approximately -162 °C (260 °F).

As mentioned above, the reduction in volume makes LNG much more cost efficient to transport over long distances where pipelines do not exist. Where transporting natural gas by pipelines is not possible or economical, it can be transported by specially designed cryogenic sea-going vessels called LNG carriers or by either cryogenic rail or road tankers.

History

Natural gas liquefaction dates back to the 1820s when British physicist Michael Faraday experimented with liquefying different types of gases. German engineer Carl Von Linde built the first practical vapor-compression refrigeration system in the 1870s.

The first commercial LNG liquefaction plant was built in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1941 and the LNG was stored in tanks at atmospheric pressure, which raised the possibility that LNG could be transported in sea-going vessels. In January 1959, the world's first LNG carrier, a converted freighter named The Methane Pioneer, containing five small, insulated aluminum tanks transported 5,000 m3 (about 2,250 metric tons[5]) of LNG from Lake Charles, Louisiana in the United States to Canvey Island in England's Thames river. That voyage demonstrated that LNG could be transported safely across the oceans. During the next 14 months, that same freighter delivered seven additional cargoes with only a few small problems.[2][3]

The demonstrated ability to transport LNG in sea-going vessels spurred the building of large-scale LNG liquefaction plants at major gas fields world-wide. The first large-scale LNG plant began operating in 1964 at Arzew, Algeria and initially produced about 2,360 metric tons/day (MT/day) of LNG. In 1969, another LNG plant began operating near Kenai, Alaska and initially produced LNG at a rate of about 3,400 MT/day.[2][4]

By mid-2008, there were 19 LNG liquefaction plants operating in 15 countries worldwide. There were also 65 LNG receiving terminals (often referred to regasification terminals) operating in 19 countries world-wide.

LNG transportation

As of 2008, a typical sea-going LNG carrier could transport about 150,000 m3 (70,000 MT) of LNG, which will become about 92,000,000 standard m3 of natural gas when regasified in a receiving terminal. LNG carriers are similar in its size to an aircraft carrier and are very expensive to build and to operate. Therefore, they cannot afford to have idle time. They travel fast, at an average speed of 18 to 20 knots, as compared to 14 knots for a sea-going crude oil carrier. Also, loading at the LNG liquefaction plants and unloading at the receiving terminals usually requires only 15 hours as an average.

In case of an accident LNG tankers have a double-hulled structure specially designed to

prevent leakage or rupture. The cargo (LNG) is carried at atmospheric pressure and -162 ºC

in specially insulated tanks (referred to as the cargo containment system) inside the inner

hull. The cargo containment structure consists of: a primary liquid container or tank; a layer

of insulation; a secondary liquid barrier; and a secondary layer of insulation. Should there

be any damage to the primary liquid tank, a secondary barrier will prevent the leakage.

All surfaces in contact with LNG are constructed of materials resistant to the extreme low

temperatures. Therefore, the material is, typically, stainless steel or aluminum or invar.

The “Moss” vessels, currently accounting for 41% of the world LNG fleet, have distinctive,

self-supporting spherical cargo tanks, normally constructed from aluminum and linked

to the ship’s hull by a “skirt” system that supports the tanks from the equator position.

Three membrane tank systems (GazTransport system, Technigaz system and CS1 system)

represent 57% of LNG vessels. The membrane designs utilise a much thinner membrane

that is supported by the walls of the hull. The GazTransport system incorporates primary

and secondary invar membranes of flat panels, while the Technigaz system uses a primary

membrane from corrugated stainless steel. The CS1 system combines invar panels of the

GazTransport system for the first insulation membrane and the triplex Technigaz membranes

(a sheet of aluminum in a fiberglass sandwich) for the second insulation.

Unlike LPG, LNG vessels usually do not have a liquefaction facility on board and use boil-off

gas for propulsion. Since the cargo (LNG) supplements fuel oil, LNG tankers do not arrive at

the destination port with the same quantities as were loaded at the liquefaction plant. The

accepted maximum figure for boil off is about 0.15% of cargo volume a day.of natural gas when regasified at the receiving terminal.. LNG carriers are

similar in its size to that of an aircraft carrier but significantly smaller than that of a Very

Large Crude Oil Carrier (VLCC). Since LNG ships are extremely capital-intensive, they cannot

“The Development of a Global LNG Market” James Jensen, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (2004).

26

Chapter 2 afford to have an idle time. They voyage fast, at an average speed of 18-20 knots compared

with 14 knots of a standard oil carrier. Also, loading and unloading of LNG do not take long,

12‑18 hours on the average.

In case of an accident LNG tankers have a double-hulled structure specially designed to

prevent leakage or rupture. The cargo (LNG) is carried at atmospheric pressure and -162 ºC

in specially insulated tanks (referred to as the cargo containment system) inside the inner

hull. The cargo containment structure consists of: a primary liquid container or tank; a layer

of insulation; a secondary liquid barrier; and a secondary layer of insulation. Should there

be any damage to the primary liquid tank, a secondary barrier will prevent the leakage.

All surfaces in contact with LNG are constructed of materials resistant to the extreme low

temperatures. Therefore, the material is, typically, stainless steel or aluminum or invar.

The “Moss” vessels, currently accounting for 41% of the world LNG fleet, have distinctive,

self-supporting spherical cargo tanks, normally constructed from aluminum and linked

to the ship’s hull by a “skirt” system that supports the tanks from the equator position.

Three membrane tank systems (GazTransport system, Technigaz system and CS1 system)

represent 57% of LNG vessels. The membrane designs utilise a much thinner membrane

that is supported by the walls of the hull. The GazTransport system incorporates primary

and secondary invar membranes of flat panels, while the Technigaz system uses a primary

membrane from corrugated stainless steel. The CS1 system combines invar panels of the

GazTransport system for the first insulation membrane and the triplex Technigaz membranes

(a sheet of aluminum in a fiberglass sandwich) for the second insulation.

Unlike LPG, LNG vessels usually do not have a liquefaction facility on board and use boil-off

gas for propulsion. Since the cargo (LNG) supplements fuel oil, LNG tankers do not arrive at

the destination port with the same quantities as were loaded at the liquefaction plant. The

accepted maximum figure for boil off is about 0.15% of cargo volume a day.

LNG Terminals

Some Statistics

Conversion data

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Frequently Asked Questions About LNG From the website of the California Energy Commission

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Introduction To LNG Michelle Michot Foss (January 2007), Center for Energy Economics (CEE), Bureau of Economic Geology, Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Michael R. Tusiani and Gordon Shearer (2007). LNG: A Nontechnical Guide, p.138. ISBN 0-87814-885-X.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Fostering LNG Trade: Role of the Energy Charter 2008, Appendices A and C, from the website of the Energy Charter Secretariat.

- ↑ Note:1 metric ton = 1 tonne = 1,000 kg = 2,204.6 pounds = 1.1023 short tons