Ampere's equation: Difference between revisions

imported>John R. Brews (use template for citation; add url) |

imported>John R. Brews mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

In [[physics]], more particularly in [[electrodynamics]], '''Ampère's equation''' describes the force between two infinitesimal elements of electric-current-carrying wires. The equation is named for the early nineteenth century French physicist and mathematician [[André-Marie Ampère]]. | In [[physics]], more particularly in [[electrodynamics]], '''Ampère's equation''' describes the force between two infinitesimal elements of electric-current-carrying wires. The equation is named for the early nineteenth century French physicist and mathematician [[André-Marie Ampère]]. | ||

Rather than giving Ampère's original infinitesimal equation, which is not without problems,<ref>E. Whittaker, ''A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity'', vol. I, 2nd edition, Nelson, London (1951). Reprinted by the American Institute of Physics, (1987). pp. 85-88 </ref><ref>{{cite journal |author= C. Christodoulides |title=Comparison of the Ampère and Biot-Savart magnetostatic force laws in their line-current-element forms |journal= American Journal of Physics|volume=vol. 56 |pages= pp. 357-362 |year=1988|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.15613 </ref> we will describe two common cases obtained by integration: a system consisting of two straight wires and a system of two closed loops. Since the integrals over disputed terms in Ampère's infinitesimal equation vanish, the equations for these integrated systems are generally accepted and, moreover, are in full agreement with experiment. | Rather than giving Ampère's original infinitesimal equation, which is not without problems,<ref> | ||

E. Whittaker, ''A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity'', vol. I, 2nd edition, Nelson, London (1951). Reprinted by the American Institute of Physics, (1987). pp. 85-88 | |||

</ref><ref> | |||

{{cite journal |author= C. Christodoulides |title=Comparison of the Ampère and Biot-Savart magnetostatic force laws in their line-current-element forms |journal= American Journal of Physics|volume=vol. 56 |pages= pp. 357-362 |year=1988|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.15613}} | |||

</ref> we will describe two common cases obtained by integration: a system consisting of two straight wires and a system of two closed loops. Since the integrals over disputed terms in Ampère's infinitesimal equation vanish, the equations for these integrated systems are generally accepted and, moreover, are in full agreement with experiment. | |||

==Electromagnetic units== | ==Electromagnetic units== | ||

Equations<ref>J. D. Jackson, ''Classical Electrodynamics'', 2nd edition, John Wiley, New York (1975) pp. 172-173</ref> will be given in two common systems of electromagnetic units ([[SI]] and [[Gaussian units]]) and to that end we define the constant ''k'' as follows, | Equations<ref>J. D. Jackson, ''Classical Electrodynamics'', 2nd edition, John Wiley, New York (1975) pp. 172-173</ref> will be given in two common systems of electromagnetic units ([[SI]] and [[Gaussian units]]) and to that end we define the constant ''k'' as follows, | ||

Revision as of 13:15, 18 April 2011

In physics, more particularly in electrodynamics, Ampère's equation describes the force between two infinitesimal elements of electric-current-carrying wires. The equation is named for the early nineteenth century French physicist and mathematician André-Marie Ampère.

Rather than giving Ampère's original infinitesimal equation, which is not without problems,[1][2] we will describe two common cases obtained by integration: a system consisting of two straight wires and a system of two closed loops. Since the integrals over disputed terms in Ampère's infinitesimal equation vanish, the equations for these integrated systems are generally accepted and, moreover, are in full agreement with experiment.

Electromagnetic units

Equations[3] will be given in two common systems of electromagnetic units (SI and Gaussian units) and to that end we define the constant k as follows,

Here μ0 is the magnetic constant (also known as vacuum permeability). The quantity c is the speed of light in vacuum, in SI units a defined value denoted by c0 = 299 792 458 m s−1 (exactly).

Two straight, infinite, and parallel wires

Consider two wires, one carrying an electric current i1, the other i2. Both currents are constant in time; the wires are infinite, straight, and parallel. If the wires are a distance r apart, by Ampère's law the force (per length l of wire) between them is,

The force F is attractive if the currents run in the same direction and repulsive if they flow in opposite direction.

This equation is used to define the SI unit A (ampere) of current. Take two infinitely long wires in vacuum at a distance r = 1 m, consider the force that one meter of these wires exert on one another (l = 1 m) and let this force be F = 2⋅10−7 N (newton). Then for i1 = i2 the current strengths are by definition both equal to one ampere (1 A). In SI units this implies that k = 10−7 N/A2 and hence that the magnetic constant is:

- μ0 = 4π k = 4π⋅10−7 N/A2.

.

Two loops

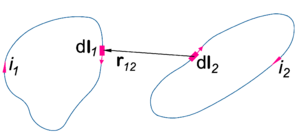

Let and be electric currents constant in time. They run in separate loops (closed curves) C1 and C2, see figure on the right, where all quantities are defined. The total force between two loops is given by the double path integral over the loops

Alternative expression

One often finds the following expression for the force between two electric-current-carrying loops:[4]

instead of the simpler expression in Eq. (1). Here the multiplication signs (×) indicate vector products. The integrand [expression under the integral of Eq. (2)] follows from the Biot-Savart-Laplace expression for the magnetic induction B(r1) due to a segment of the second loop. Insertion of B(r1) into the Lorentz force that acts on the current in segment dl1 gives the integrand of Eq. (2).

The labeling of the segments being arbitrary, one would expect the same force (in absolute value) when the labels 1 and 2 are interchanged, or in other words, one would expect Newton's third law (action is minus reaction) to hold. This is not the case, the integrand in equation (2) is non-symmetric under interchange of labels 1 and 2 and hence the integral also appears to be non-symmetric. However, after integration the expression becomes antisymmetric (changes sign under interchange of 1 and 2) and hence satisfies Newton's third law.

To see this we note that the force in Eq. (2) has in fact two contributions, as follows from a result well-known in vector analysis,

The second contribution gives an integral that is obviously equal to Eq. (1), which is manifestly antisymmetric under interchange of labels (the dot product does not change, the vector r12 changes sign). We will show that the first contribution vanishes after integration over a closed curve.

Write

where A is a short hand notation. Applying Stokes' theorem, we find that the first contribution becomes

It is well-known in vector analysis that

for any scalar function Φ and in particular for Φ ≡ 1/|r12|. Hence the first contribution to the force of Eq. (2) vanishes.

History

Ampère's original force law is:[5]

with û12 a unit vector pointing along the line joining element 2 to element 1 and r12 the length of this line. The force element is second order because it is a product of two infinitesimals. This force law leads to the same force between closed current loops as the more commonly used Grassmann's law presented above:

Grassmann's law is readily derived from the Biot-Savart law, and is consistent with space-time symmetry. Unlike Ampère's law, Grassmann's law obviously is not symmetric under exchange of the indices i and j, and violates Newton's law of action and reaction, but this behavior stems from not being based upon action-at-a-distance.[6] There exists some debate over the ultimate form of the force law between current elements.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ E. Whittaker, A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity, vol. I, 2nd edition, Nelson, London (1951). Reprinted by the American Institute of Physics, (1987). pp. 85-88

- ↑ C. Christodoulides (1988). "Comparison of the Ampère and Biot-Savart magnetostatic force laws in their line-current-element forms". American Journal of Physics vol. 56: pp. 357-362.

- ↑ J. D. Jackson, Classical Electrodynamics, 2nd edition, John Wiley, New York (1975) pp. 172-173

- ↑ For example, Perambur S. Neelakanta (1995). Handbook of electromagnetic materials. CRC Press, p. 10. ISBN 0849325005. and Bhag S. Guru, Hüseyin R. Hızıroğlu (2004). “Ampère's force law”, Electromagnetic field theory fundamentals, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, p. 183. ISBN 0521830168.

- ↑ See for example, André Koch Torres Assis (1994). Weber's electrodynamics. Springer, p. 86. ISBN 0792331370. , or Marcelo de Almeida Bueno, André Koch Torres Assis (2001). “§5.1: Ampère's force”, Inductance and force calculations in electrical circuits. Nova Science Publishers, pp. 51 ff. ISBN 9781560729174.

- ↑ Thomas E Phipps, Jr. (Autumn, 1990). "Weber-like laws of action-at-a-distance in modern physics". Aperion No. 8.

- ↑ For a discussion, see and P Graneau and N Graneau (2001). "Electrodynamic force law controversy". Phys Rev vol 63 (Issue 5). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevE.63.058601. Research Blogging.

![{\displaystyle -ki_{1}i_{2}\oint _{C_{2}}\left[\oint _{C_{1}}(d{\boldsymbol {l}}_{1}\cdot \mathbf {A} )\,\right]d{\boldsymbol {l}}_{2}=-ki_{1}i_{2}\oint _{C_{2}}\left[\iint _{S}({\boldsymbol {\nabla }}_{1}\times \mathbf {A} )\cdot d\mathbf {S} _{1}\,\right]d{\boldsymbol {l}}_{2}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8ba745837dbe48069b9b2592e33e171d114ca160)