Battle of Dien Bien Phu: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

| edition = 4rd | | edition = 4rd | ||

| year = 1967}}, pp. 314-315</ref> | | year = 1967}}, pp. 314-315</ref> | ||

Even with the much greater historical material available today, there are still inconsistencies in timelines and other information about the battle. The French command structure, which was to some degree split, is confusing both in its very makeup, the authorities at any given point, and the taking of actions while apparently simultaneously in possession of intelligence suggesting an action would be unwise. Unity of command, or having a single final decisionmaker, is a repeated problem during the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, unity of command problems were evident at the 1963 [[Battle of Ap Bac]], with disagreements internal to South Vietnamese commanders, internal to U.S. advisory command, and Vietnamese-American relationships. There were unity of command problems in the 1972 [[Operation LINEBACKER II]] all-American bombing of the North. | |||

The timing of the first Communist response, especially deliberate ones rather than immediate response to the paratrooper, is not clear. In particular, various accounts of the dynamics among Giap's headquarters, the Lao Dong Party (i.e., Indonesian/Vietnamese Communist leadership), and the Chinese Military Assistance Group (CMAG) as well as Chinese Politburo have inconsistencies. Some reports have the Chinese advisors demanding an immediate attack on the paratroopers still forming, some suggest it never happene, and others say Giap started but then stopped it to move to a more deliberate approach. There are also reports that some Chinese decisions reflected, very quickly, the results of secret U.S.-French meetings in Washington, with a distinct lack of clarity about how the Chinese learned about things held tightly in Western governments. | |||

Even though there are joint Vietnamese-Western historical meetings, some of the truth may never be known, since most of the key officials have died. Giap, while retired, is one of the few living principals. See the talk page and bibliography for possible sources, not in English, which may add information. | |||

==The place== | ==The place== | ||

| Line 104: | Line 110: | ||

He knew, however, that his own strength was in well-protected [[howitzer]]s and [[anti-aircraft artillery]]. | He knew, however, that his own strength was in well-protected [[howitzer]]s and [[anti-aircraft artillery]]. | ||

==Possible U.S. | ==Possible external relief== | ||

GEN Paul Ely, Chief of Staff of France, visited the U.S. | Other countries, as well as other French forces, were monitoring the situation. It is a matter of record that U.S. transport pilots, such as the legendary Earthquake McGoon,<ref name=>{{citation | ||

| title = Remains of 'Earthquake McGoon' sought after 48 years | |||

| first = Richard Pyle | |||

| journal = Associated Press | |||

| date =Nov. 24, 2002 | |||

| url = http://www.air-america.org/newspaper_articles/Earthquake_McGoon.shtml}}</ref>were flying missions to Dien Bien Phu, to drop supplies. They worked for a [[Central Intelligence Agency]] proprietary airline called Civil Air Transport. | |||

While the CAT personnel, a number of whom were shot down, clearly would drop military supplies, it is not clear if they were prepared for the greater structure of a paratroop operation. | |||

===Operation Damocles=== | |||

This was a French contingency plan, more directed at a [[Korean War]]-style invasion more than at Dien Bien Phu specifically. It also assumed the use of U.S. air power, and it would have French forces fall back to a defensible position in the Red River Delta, much as U.S. and Republic of Korea forces would fall back to the [[Pusan Perimeter]] in 1950. <ref>Fall, HVSP, p. 297</ref> | |||

Aspets of Damocles may have been discussed, among with other contingencies, by GEN Paul Ely, Chief of Staff of France, visited the U.S. starting on March 20. | |||

===Operation VULTURE=== | |||

Ely's mission was not, initially, to ask for isolated help at Dien Bien Phu, but to ensure U.S. support should there be overt Chinese intervention. He also wanted U.S. help at the Geneva talks on Vietnam; France had already made the policy decision that Indochina would eventually be lost, and they wanted a stronger position at Geneva. Ely believed U.S. ground forces would merely prolong and worsen the situation. <ref name=Lathers>{{citation | |||

| first = John D. | last = Lathers | | first = John D. | last = Lathers | ||

| url = http://www.thepresidency.org/pubs/fellows2007/Lathers.pdf | | url = http://www.thepresidency.org/pubs/fellows2007/Lathers.pdf | ||

| Line 118: | Line 137: | ||

| author = Eisenberg, Michael T. | | author = Eisenberg, Michael T. | ||

| publisher = St. Martin's Press | year = 1993}} pp. 607-608</ref> | | publisher = St. Martin's Press | year = 1993}} pp. 607-608</ref> | ||

Reports of Vulture planning differ as to whether the use of nuclear weapons was considered, although it is fairly clear that there would be extensive use of U.S. [[B-29 Superfortress]] heavy land-based bombers. Gen Earle Partridge, commanding U.S. Far Eastern Air Force (FEAF), and BG Joseph Caldera, FEAF bomber commander, did fly an assessment mission in April; he found many practical problems with the draft proposals.<ref name=Simpson>{{citation | |||

| title = Dien Bien Phu: The Epic Battle America Forgot | |||

| first1 = Howard R. | last1 = Simpson |first2 = Stanley | last2= Karnow | |||

| publisher = Brassey's | year = 2005 | |||

| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=_zQXdSO4430C&pg=PA119&lpg=PA119&dq=Caldera+%22Dien+Bien+Phu%22&source=bl&ots=WVKYGZ1HQ5&sig=U89IyVqHDrFf6n1yFezyBo5FguI&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA118,M1}}, pp. 318-319</ref> Assessments of feasibility differ; another report says that Caldera thought a day mission was feasible and could be launched in 72 hours. <ref name=Windrow>{{citation | |||

| title = The Last Valley | |||

| first = Martin | last = Windrow | publisher = Da Capo Press | year = 2004 | |||

| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=haaacvBb0YgC&pg=RA1-PA567&lpg=RA1-PA567&dq=Caldera+%22Dien+Bien+Phu%22&source=web&ots=PLRXr0Mlep&sig=mah9py_NSYMaNGDZhgUtVoXE3pA&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=4&ct=result}}, p.567 </ref> | |||

One technical unknown involves the weather over Dien Bien Phu. In principle, B-29 bombers could bomb fairly accurately, especially in daylight, above the range of Vietnamese antiaircraft guns. That was also true in principle over Japan in the [[Second World War]], but unexpected high-altitude winds made that impossible. Still using unguided bombs, however, U.S. [[B-52]] bombers were able to carry out accurate high-altitude bombing over the North during the 1972 [[Operation LINEBACKER II]]. | |||

===Operations Albatross and Eoodpecker=== | |||

Navarre considered a high-risk breakout of the garrison, moving toward Laos, which he mentioned to Ely in an April 30 message. During this time, Navarre's intelligence obtained a high-level [[clandestine human-source intelligence]] source in Ho Chi Minh's government, which gave some perspective. | |||

Operation Albatross would involve dropping paratroops, for which the airlift might not have been obtainable, outside the base, to facilitate the breakout. Operation Woodpecker (''Pivert'') would drop paratroops only after a breakout had started. At least part of Condor was attempted. <ref>Fall, HVSP, pp. 314-319</ref> | |||

==The Main Assault== | ==The Main Assault== | ||

According to Zhai, the Viet Minh hesitated in April, partially due to weather and partially due to potential U.S. assistance. It was not, however, indicated how China learned of the high-level Ely-Radford discussions. <ref>Zhai, pp. 48-49</ref> | According to Zhai, the Viet Minh hesitated in April, partially due to weather and partially due to potential U.S. assistance. It was not, however, indicated how China learned of the high-level Ely-Radford discussions. <ref>Zhai, pp. 48-49</ref> | ||

==Aftermath== | ==Aftermath== | ||

French commanders outside the base, even when it was clearly to fall, made various recommendations for limited breakouts, but were very insistent that while the French forces might stop fighting, they must not raise the symbolic white flag. In turn, French troops generally rejected breakouts by the few that were able; they would abandon too many wounded. As one put it, referring to a legendary [[French Foreign Legion]] fight to the death, you can do [[Camerone]] with a small force, but not with 10,000. As a minor note, however, on April 30, one of the airdrops of supplies considered necessary by the French, including wine, did successfully land in Legionnaire positions on Camerone Day, April 30; there were many volunteers for counterattacks. <ref>Fall, HVSP, pp. 347-348</ref> | |||

The Viet Minh did not have the medical or military police resources to deal with the number of prisoners, but the prisoners were treated harshly even understanding those constraints. Part of the reason may have been Vietnamese recognition of the bargaining value of [[prisoner of war|prisoners of war]], much as the North Vietnamese did with U.S. aircrew in 1964-1972. Viet Minh treatment was harsh in general; no seriously wounded prisoners survived. Still, there seems to have been especially bad treatment, which Fall describes as a "Death March", for the Dien Bien Phu survivors, followed by extensive political indoctrination and other hardships in prison camps. <ref>Fall, SWJ, pp. 300-308</ref> | |||

==Lessons learned== | ==Lessons learned== | ||

When North Vietnamese and American troops faced one another at another remote valley, both sides had Dien Bien Phu in mind at the [[Battle of Khe Sanh]]. | When North Vietnamese and American troops faced one another at another remote valley, both sides had Dien Bien Phu in mind at the [[Battle of Khe Sanh]]. | ||

Giap invited Moore and Galloway to visit the battlefield, saying he did not understand why the U.S. had not studied the war of the Viet Minh against the French, and Dien Bien Phu specifically. If the Americans, according to Giap, had studied what happened to the French, they would never have come halfway across the world to take their place and suffer as bad an ending. <ref>Moore & Galloway 2008, pp. 130-131</ref> He pressed the point that the Americans were paying for the operation, which Fall denies, saying U.S. expenditures, between 1946 and 1954, were $954 million where comparable French costs were $11 billion.<ref>Fall SWJ, p. 314</ref> | Giap invited Moore and Galloway to visit the battlefield, saying he did not understand why the U.S. had not studied the war of the Viet Minh against the French, and Dien Bien Phu specifically. If the Americans, according to Giap, had studied what happened to the French, they would never have come halfway across the world to take their place and suffer as bad an ending. <ref>Moore & Galloway 2008, pp. 130-131</ref> He pressed the point that the Americans were paying for the operation, which Fall denies, saying U.S. expenditures, between 1946 and 1954, were $954 million where comparable French costs were $11 billion.<ref>Fall SWJ, p. 314</ref> | ||

Revision as of 05:52, 26 November 2008

Template:TOC-right Dien Bien Phu is a valley and small town in North Vietnam, 260 miles northwest of Hanoi and the place of the 1954 decisive battle that soon forced France to relinquish control of colonial Indochina. In military shorthand, Dien Bien Phu has also become a synonym for an extremely unwise decision: the attempt to hold a seemingly strong defensive position, against which the enemy, cooperating with the defender's plans, will then destroy himself against the impregnable fortifications.

Unfortunately, the Viet Minh, commanded by Vo Nguyen Giap, did not play the part the French commander, Henri Navarre, had written for them. Navarre, in turn, believed his government had set a policy that he must follow: defend northern Laos. The French commission of inquiry, however, believed that the highest political authority had set Navarre's highest priority as protecting the French Expeditionary Force. [1]

Even with the much greater historical material available today, there are still inconsistencies in timelines and other information about the battle. The French command structure, which was to some degree split, is confusing both in its very makeup, the authorities at any given point, and the taking of actions while apparently simultaneously in possession of intelligence suggesting an action would be unwise. Unity of command, or having a single final decisionmaker, is a repeated problem during the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, unity of command problems were evident at the 1963 Battle of Ap Bac, with disagreements internal to South Vietnamese commanders, internal to U.S. advisory command, and Vietnamese-American relationships. There were unity of command problems in the 1972 Operation LINEBACKER II all-American bombing of the North.

The timing of the first Communist response, especially deliberate ones rather than immediate response to the paratrooper, is not clear. In particular, various accounts of the dynamics among Giap's headquarters, the Lao Dong Party (i.e., Indonesian/Vietnamese Communist leadership), and the Chinese Military Assistance Group (CMAG) as well as Chinese Politburo have inconsistencies. Some reports have the Chinese advisors demanding an immediate attack on the paratroopers still forming, some suggest it never happene, and others say Giap started but then stopped it to move to a more deliberate approach. There are also reports that some Chinese decisions reflected, very quickly, the results of secret U.S.-French meetings in Washington, with a distinct lack of clarity about how the Chinese learned about things held tightly in Western governments.

Even though there are joint Vietnamese-Western historical meetings, some of the truth may never be known, since most of the key officials have died. Giap, while retired, is one of the few living principals. See the talk page and bibliography for possible sources, not in English, which may add information.

The place

That the correct Vietnamese name for the area is not even Dien Bien Phu characterizes the misunderstandings that went into the battle. Properly, the area centers on a village called Muong Thanh by the T'ai tribesmen of the area. [2]

- Henri Navarre

- Jean-Louis Nicot, air transport commander

- Jean Gilles, overall airborne commander

- Christian de Castries, Dien Bien Phu base commander

- Charles Piroth, artillery commander and second in command

- Marcel Bigeard, airborne battalion commander

- Charles Piroth, artillery commander and second in command

Previous military use

In 1952, Giap had recognized the French were weak in Laos, and sent three divisions and an independent regiment southwest from his mountainous bases. They pushed the French back, clearing road junctions and capturing small towns including Muong Thon, also known as Dien Bien Phu.

He was able to lay siege to the capital of the capital at Luang Prabang, but, learning caution, decided not to press the attack into the rainy season. In November, French paratroopers recaptured the town, although this was not part of the main fortification. Both sides decided to reinforce for the battle that would begin in March. [3]

Communist strategy

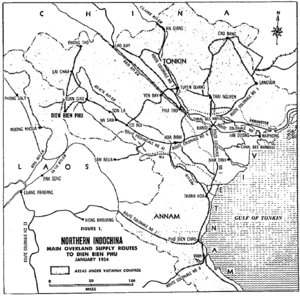

Dien Bien Phu was part of a larger Viet Minh strategy, to force the French to commit their mobile forces to static defense and lose the operational initiative.[4] In parallel with it, they marched divisions into the northwest, attacking local "bandits" and attacking the French column retreating from Lai Chau. They saw the French as losing initiative and mobility, as they concentrated at Dien Bien Phu and in the Red River Delta (i.e., Hanoi-Haiphong area).

Another offensive struck out toward middle Laos, especially the airfield at Seno. Threatening Seno forced the French to commit yet more mobile forces to static defense. The Viet Minh plan was to leave only a small reserve to protect the rear, while attacking the Western highlands. Kontum was taken and the French had to form yet another static defense at Pleiku.

In Upper Laos, Viet Minh troops threatened Luang Prabang, again forcing static defense.

French strategy

"Mission creep" was among the many French military sins. Originally, Navarre had planned to block Viet Minh access to Laos, and interfere with Giap's supply lines and his drug trade. As the Geneva conference of 1954 approached, however, he felt under pressure to produce a decisive victory.[5] Giap saw the Navarre plan as intending to defend the Red River Delta and leave other forces mobile. [6]

Navarre, an armor officer, thought the flat valley would be ideal; he flew in 32 tanks, which were defeated by mud; only 2 were usable when the final attack came. Even Navarre, however, believed that the greatest strength of the garrison was artillery, commanded by COL Charles Piroth. [7]

Seizing the base

On November 23, 1953, the French dropped a paratroop force into Dien Bien Phu, using 65 transport aircraft, supported by fighters and bombers. [8] Once landed, the paratroopers would improve the airfield, so heavier equipment could be landed. There was confusion, however, on just what equipment and troops would eventually be needed. Approximately two weeks before the jumps into Dien Bien Phu, French intelligence learned that regular Communist units were in the area, equipped with artillery that paratroop units could not match. Eventually, heavier units would be needed; the later replacement of the Airborne commander with an armor officer would suggest this was soon realized. [9]

BG Jean Gilles, the Airborne commander, expected some resistance, so he used the best available troops for the first landing:

- 6th BCP (Colonial Parachute Battalion), commanded by MAJ Marcel Bigeard, 651 men

- II/1 RCP (2nd Battalion, 1st Regiment of Parachute Light Infantry), MAJ Jean Bréchignac, 569 men

- 17th Company of Airborne Combat Engineers

- battery of 35th Airborne Artillery Regiment, MAJ Jean Milot

- Headquarters, Airborne Battle Group No. 1 (GAP 1)

All the basic complement of paratroops were in place by the 22nd. Gilles went back to overall airborne command, and was replaced by COL Bastiani's airborne group headquarters. On December 12, LTC Pierre Langlais, a regular army officer, arrived as deputy to COL Christian de Castries, an armor officer who was being given overall command of the area.

Initial buildup

Eight 105mm howitzers of the Autonomous Laotian Artillery Battery landed on the improved airstrip, on November 28. Better artillery followed.[10]

On November 30, paratroop units under Capt. Pierre Tourret began to maneuver out of the base, with the intention of linking up with French-led guerillas. Outside the Dien Bien Phu area, Groupement de Commandos Mixtes Aeroportes (GCMA) guerillas under Roger Trinquier moved toward the position. GCMA had some similarities to the later MACV-SOG, as a principally covert operations force.

On December 5th, Tourret's force ran into heavy Viet Minh opposition, and were able to return only with artillery support from the base. They did not successfully link up with the GCMA force.

Between December, and the main Communist attacks of March, the French built a position, at the bottom of a valley, of a set of strongpoints, with three main artillery firebases.

Viet Minh response

While the French were in static defense, Giap considered it a strong position. Previously, he had avoided the French strength, after the lesson of the Battle of Vinh Yen.

It was quite proper military thinking for him to ask if he could be certain of victory in attacking Dien Bien Phu. No matter how important it might be to the Navarre Plan, no matter how much it might be a center of gravity, he knew he should attack it if and only if he was confident of victory. A fundamental principle of revolutionary war, according to Giap, was "strike to win, strike only when success is certain; if it is not, don't strike."[11]

The immediate question was whether to "strike swiftly and win swiftly, or strike surely and attack surey." The first option would have meant attacking the paratroopers before they had consolidated. Still, even in the early days, "our troops lacked experience in attacking fortified entrenched camps", and even the first French forces fortified from the beginning. Still, there was an initial attack.

Arguing against a quick strike was that it was cut off by land, in a mountainous area, and could be supplied only by air. The Viet Minh could keep the initiative, by concentrating troops and using the immense rear to keep them supplied. [12]

Immediate response

Contrary to Giap's analysis, he did launch a first "human wave" assault in January 1954, partially at the recommendation of a Chinese advisor, Gen. Wei Guoqing. [13] Wei was the original head of the Chinese Military Assistance Group, assigned to it in April 1950. [14] Senior General Chen Geng joined CMAG in July 1950; throughout the war, he was insistent on his advice being followed, including at Dien Bien Phu; he would call Ho or Mao with his recommendations and threatened Giap with his resignation if Giap did not follow his plan. [15] These attacks failed both because Viet Minh artillery was not in position as yet, and the French reinforced faster than the Chinese advisors had expected. The Chinese central command ordered Wei to abandon the direct attack and "strive to eliminate one battalion at a time." China sent antiaircraft and engineering experts to help isolate Dien Bien Phu.[16]

Giap then changed the plan. Karnow quoted Bui Tin as saying "[Giap] changed the entire plan. He stpped the attack and pulled back our artillery. Now the shovel became our most important weapon."[17]

Realignment

After Giap had drawn the French strength toward Dien Bien Phu, he used backbreaking human work to bring howitzers and anti-aircraft artillery into the hills surrounding the French base. He used his laborers to dig the weapons into impregnable positions: a cannon could fire and be quickly pulled back into the safety of a cave.

He had had orders from the North Vietnamese Politburo to launch human-wave attacks on January 26, which he concluded would play into the French strength. Instead, possibly endangering his life, he called off the order, and continued fortification and besieging until March 13.[18]

He knew, however, that his own strength was in well-protected howitzers and anti-aircraft artillery.

Possible external relief

Other countries, as well as other French forces, were monitoring the situation. It is a matter of record that U.S. transport pilots, such as the legendary Earthquake McGoon,[19]were flying missions to Dien Bien Phu, to drop supplies. They worked for a Central Intelligence Agency proprietary airline called Civil Air Transport.

While the CAT personnel, a number of whom were shot down, clearly would drop military supplies, it is not clear if they were prepared for the greater structure of a paratroop operation.

Operation Damocles

This was a French contingency plan, more directed at a Korean War-style invasion more than at Dien Bien Phu specifically. It also assumed the use of U.S. air power, and it would have French forces fall back to a defensible position in the Red River Delta, much as U.S. and Republic of Korea forces would fall back to the Pusan Perimeter in 1950. [20]

Aspets of Damocles may have been discussed, among with other contingencies, by GEN Paul Ely, Chief of Staff of France, visited the U.S. starting on March 20.

Operation VULTURE

Ely's mission was not, initially, to ask for isolated help at Dien Bien Phu, but to ensure U.S. support should there be overt Chinese intervention. He also wanted U.S. help at the Geneva talks on Vietnam; France had already made the policy decision that Indochina would eventually be lost, and they wanted a stronger position at Geneva. Ely believed U.S. ground forces would merely prolong and worsen the situation. [21]

Ely obtained greater support from Admiral Arthur Radford, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag Radford was the strongest proponent of greater U.S. involvement, certainly including heavy bomber strikes around the Dien Bien Phu perimeter. Eisenhower had already rebuked Radford, on April 5, for misleading Ely about the chance of U.S. support. He told Radford, who, at the time, was not supported by any of the other chiefs, that the proposal was politically impossible. Even the hard-line Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, agreed it would be possible only with British agreement [22]

Reports of Vulture planning differ as to whether the use of nuclear weapons was considered, although it is fairly clear that there would be extensive use of U.S. B-29 Superfortress heavy land-based bombers. Gen Earle Partridge, commanding U.S. Far Eastern Air Force (FEAF), and BG Joseph Caldera, FEAF bomber commander, did fly an assessment mission in April; he found many practical problems with the draft proposals.[23] Assessments of feasibility differ; another report says that Caldera thought a day mission was feasible and could be launched in 72 hours. [24]

One technical unknown involves the weather over Dien Bien Phu. In principle, B-29 bombers could bomb fairly accurately, especially in daylight, above the range of Vietnamese antiaircraft guns. That was also true in principle over Japan in the Second World War, but unexpected high-altitude winds made that impossible. Still using unguided bombs, however, U.S. B-52 bombers were able to carry out accurate high-altitude bombing over the North during the 1972 Operation LINEBACKER II.

Operations Albatross and Eoodpecker

Navarre considered a high-risk breakout of the garrison, moving toward Laos, which he mentioned to Ely in an April 30 message. During this time, Navarre's intelligence obtained a high-level clandestine human-source intelligence source in Ho Chi Minh's government, which gave some perspective.

Operation Albatross would involve dropping paratroops, for which the airlift might not have been obtainable, outside the base, to facilitate the breakout. Operation Woodpecker (Pivert) would drop paratroops only after a breakout had started. At least part of Condor was attempted. [25]

The Main Assault

According to Zhai, the Viet Minh hesitated in April, partially due to weather and partially due to potential U.S. assistance. It was not, however, indicated how China learned of the high-level Ely-Radford discussions. [26]

Aftermath

French commanders outside the base, even when it was clearly to fall, made various recommendations for limited breakouts, but were very insistent that while the French forces might stop fighting, they must not raise the symbolic white flag. In turn, French troops generally rejected breakouts by the few that were able; they would abandon too many wounded. As one put it, referring to a legendary French Foreign Legion fight to the death, you can do Camerone with a small force, but not with 10,000. As a minor note, however, on April 30, one of the airdrops of supplies considered necessary by the French, including wine, did successfully land in Legionnaire positions on Camerone Day, April 30; there were many volunteers for counterattacks. [27]

The Viet Minh did not have the medical or military police resources to deal with the number of prisoners, but the prisoners were treated harshly even understanding those constraints. Part of the reason may have been Vietnamese recognition of the bargaining value of prisoners of war, much as the North Vietnamese did with U.S. aircrew in 1964-1972. Viet Minh treatment was harsh in general; no seriously wounded prisoners survived. Still, there seems to have been especially bad treatment, which Fall describes as a "Death March", for the Dien Bien Phu survivors, followed by extensive political indoctrination and other hardships in prison camps. [28]

Lessons learned

When North Vietnamese and American troops faced one another at another remote valley, both sides had Dien Bien Phu in mind at the Battle of Khe Sanh.

Giap invited Moore and Galloway to visit the battlefield, saying he did not understand why the U.S. had not studied the war of the Viet Minh against the French, and Dien Bien Phu specifically. If the Americans, according to Giap, had studied what happened to the French, they would never have come halfway across the world to take their place and suffer as bad an ending. [29] He pressed the point that the Americans were paying for the operation, which Fall denies, saying U.S. expenditures, between 1946 and 1954, were $954 million where comparable French costs were $11 billion.[30]

Moore, at LZ X-ray, remembered the Viet Minh tactics at Dien Bien Phu and those of the North Korean People's Army in the Korean War, and that they had always made frontal attacks. He drew on that historical knowledge, when he was short on troops, in "leaving our back door open" until reinforced. [31]

References

- ↑ Fall, Bernard B. (1967), Street without joy: insurgency in Indochina, 1946-63 (4rd ed.), Schocken, SWJ, pp. 314-315

- ↑ Bernard B., Fall (1967), Hell in a Very Small Place: the Siege of Dien Bien Phu, J. B. Lippincott, HVSP, pp. 23-24

- ↑ Mallin, Jay (1973), General Vo Nguyen Giap, North Vietnamese Military Commander, Samhar Press, pp. 12-15

- ↑ Vo Nguyen Giap (1962), People's war, People's Army, Praeger, PWPA, pp. 161-162

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, p. 129

- ↑ Giap, PWPA, p. 163

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, pp. 135-136

- ↑ Fall, HVSP, pp. 1-4

- ↑ Fall, HVSP, pp. 38-39

- ↑ Fall, HVSP, p. 53-54

- ↑ Giap, PWPA, p. 170

- ↑ Giap, PWPA, pp. 168

- ↑ Karnow, p. 195

- ↑ Xiaobing Li (2007), A History of the Modern Chinese Army, University of Kentucky Press, p. 208

- ↑ Li, pp. 210-212

- ↑ Qiang Zhai (2000), China and the Vietnam Wars, 1950-1975, UNC Press, p. 46

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley (1983), Vietnam, a History, Viking Press, p. 196

- ↑ Moore, Harold G. (Hal) & Joseph L. Galloway (2008), We are soldiers still: a journey back to the battlefields of Vietnam, Harper Collins, pp. 45-46}}

- ↑ "Remains of 'Earthquake McGoon' sought after 48 years", Associated Press, Nov. 24, 2002

- ↑ Fall, HVSP, p. 297

- ↑ Lathers, John D., The Influence of the Considerations of Hearts and Minds on Eisenhower’s Decision Not to Assist the French at Dien Bien Phu

- ↑ Eisenberg, Michael T. (1993), Shield of the Republic, Volume I (1945-1962), St. Martin's Press pp. 607-608

- ↑ Simpson, Howard R. & Stanley Karnow (2005), Dien Bien Phu: The Epic Battle America Forgot, Brassey's, pp. 318-319

- ↑ Windrow, Martin (2004), The Last Valley, Da Capo Press, p.567

- ↑ Fall, HVSP, pp. 314-319

- ↑ Zhai, pp. 48-49

- ↑ Fall, HVSP, pp. 347-348

- ↑ Fall, SWJ, pp. 300-308

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, pp. 130-131

- ↑ Fall SWJ, p. 314

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, p. 134