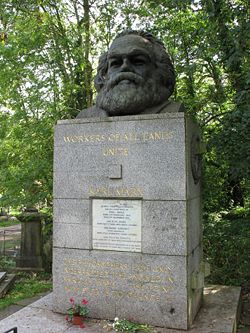

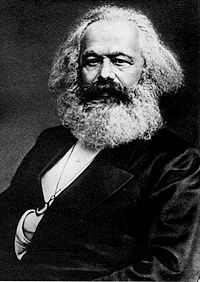

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (1818-1883) was the most important of all socialist thinkers and the creator of a system of thought called Marxism, and the political system called Communism. He helped organize the international socialist movement. His ideas motivated radical political activists who joined his call to overthrow capitalism. Marxism, reduced to the theory that all events are caused by economic self interest, had a strong influence on many areas of thought from politics to history to literature, although it cut rather little swath in the discipline of economics itself.

Career

Karl Heinrich Marx was born into a happy, wealthy middle-class home in the Rhineland city of Trier, in Germany. On both sides of his family, he came from a long line of Jewish rabbis; but his father Heinrich Marx (1782-1838), an intellectual and highly respected lawyer, and family converted to Lutheranism in 1824. Marx received a good classical education; at age 17, he spent a year in the University of Bonn's law faculty and soaked up its cultural romanticism. At age 18 he became engaged to aristocratic Jenny von Westphalen (1814-1881), daughter of Baron von Westphalen, a prominent member of Trier society, grandaughter of a famous general, and also descended from Scottish nobility. She interested Marx in romantic literature and in the utopian socialist Saint-Simonian movement.

Intellectual roots

In 1836 Marx transferred to the University of Berlin, at the time the foremost scholarly center in the world. He abandoned his superficial romanticism and came under the influence of the philosophy of the recently deceased G. W. F. Hegel. which dominated German thought. Lectures were less important than long conversations with Young Hegelian intellectuals, notably Bruno Bauer; they sought to use Hegelianism to battle the German religious, political, and philosophical status quo. After completing his doctoral thesis (which dealt with the atomic theories of Democritus and Epicurus), Marx at first hoped to obtain teaching post. When Bauer was dismissed for unorthodoxy in 1842, Marx turned to journalism and began writing for the Rheinische Zeitung, an opposition daily backed by liberal Rhenish industrialists. He soon became its editor, but the paper was closed by the authorities in May 1843, following an expose by Marx of the miserable poverty of farm workers in the Moselle vinyards, a piece of work that led him, as his friend Friedrich Engels later said, "from pure politics to economic relationships and so to socialism."

Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-72) in his 1841 book The Essence of Christianity strongly influenced Marx, who responded with "Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Law. Introduction (1843-44), which includes his famous line that "religion is the opium of the masses." Marx wanted freedom from religion, claiming there would no longer be a need for it once socialism succeeded.

In 1843, Marx married Jenny von Westphalen and composed a lengthy manuscript definitely rejecting Hegel's apologia for contemporary German politics. Unemployable in Germany, Marx decided to emigrate to Paris.

Paris and Brussels

In Paris Marx discovered a hothouse of innumerable socialist sects. A proposed journal collapsed, and he plunged into a program of exhasutive readfing in politics, history and economics. In 1844 Marx composed a series of treatises known as the "Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts" or "Paris Manuscripts," in which he finally espoused "communism". He began a lifelong friendship and collaboration with Friedrich Engels, whose father was a partner in a cotton firm in the English city of Manchester. Engels supplied Marx with a practical knowledge of the daily workings of capitalism, as well as generous cash subsidies and the one firm intellectual friendship that lasted until death.

On expulsion from Paris in the autumn of 1844, Marx settled (for the next three years) in Brussels, renewing his study of economics. He visited England, with Engels as his guide, and in London met the leaders of the League of the Just, a semiclandestine club of emigre German artisans. In Brussels Marx founded a network of correspondence committees to keep German, French, and English communists and socialists informed about each other's ideas and activities and to introduce some theoretical unity into the movement.

He devoured the works of economists Adam Smith, David Ricardo, the comte de Saint-Simon, and many others. He rejected the individualistic radicalism of Pierre Joseph Proudhon and attacked him in The Poverty of Philosophy (1847), an early attempt to systematize his own thought.

By 1847 the League of the Just was conscious of a need for a more firm theoretical foundation. Marx and Engels were approached and proved eager to help. During two long congresses in London, Marx's ideas were accepted in principle by the organization, now renamed the Communist League, and Marx was commissioned to set them down in writing.

Communist Manifesto

The classic "Communist Manifesto" by Marx and Engels called for the working classes to rise in rebellion. Eric Hobsbawm has argued there was a "triumphal march" of capitalism after the European revolutions of 1848-49, which proves that Marx and Engels were completely wrong in their prognosis of the rapid intensification of class conflict and the destruction of capitalism. From 1848-49 onward the European bourgeoisie implemented successfully various reforms that insured their hegemony and confounded the prognosis of the "Manifesto".

Revolution of 1848

Just as soon as the "Communist Manifesto" appeared, but unrelated to its publication, rebellions erupted in Europe in which workers and intellectuals, and even some members of the middle classes participated. The first of the revolutions of 1848, broke out in Paris. Marx rushed back to Paris at the invitation of the liberal provisional government that had replaced the government of King Louis Philippe. By March 1848, the revolution had reached Prussia, and in Berlin King Frederick William IV had been compelled to grant an elected parliament, a free press, and the convening of an assembly to draw up a new constitution. Marx hurried to Cologne (part of Prussia), and resumed his journalistic activities, concentrating his energies on a new paper, the "Neue Rheinische Zeitung," which under his editorship favored an alliance between the German workers' movement and the more progressive elements of the middle class. By autumn, 1848, the revolution had been defeated in France and in the Austrian Empire. Marx still favored such an alliance and refused to support separate working-class candidates in elections. Not until April 1849, a month before the final collapse of the revolution in Germany, did he change tactics and advocate separate working-class political action. But it was far too late. Marx returned once again to Paris, expecting the revolution to succeed there; it did not and he was expelled in July 1849. Marx returned to London to begin his long exile.

London

The early years in London were characterized by grinding poverty, due quite as much to Marx's inability to manage his finances as to their inadequacy. Three of his six children died. Three of his daughters reached maturity, as did an illegitimate son borne by the Marx family servant, a son whose true parentage remained a secret until after Engels' death. In 1856 a small legacy enabled Marx to move into a more adequate house, but what he conceived to be the necessity of keeping up appearances soon renewed his financial difficulties. Not until 1864 did the death of his mother and a legacy from an old Communist comrade, bring him substantial relief. But as Marx's pecuniary worries receded, his health deteriorated; he was plagued by boils from head to foot. Despite these difficulties, Marx enjoyed a very warm home life. He loved to play with his children, and the week regularly culminated with a Sunday picnic accompanied by singing and recitations from Shakespeare.

Marx rejoined the Communist League and resumed his journalistic activities. But the study of economics had convinced him that "a new revolution is possible only in consequence of a new crisis," an economic crisis.

Marx's views

Russia

Initially, Marx's attitudes were marked by Russophobia, pronounced anti-Pan-Slavism, and assessments of Russia as an outpost of European reaction and counterrevolution, and even as the head of a conspiracy to block the world revolution. With time, however, Marx came to consider Russia as the country in which the outbreak of the revolution was most likely. In his research for successive volumes of Capital, he read Russian theoretical works by, among others, Vasili Bervi-Flerovski and A. I. Koshelev. Marx's attitudes to the anticipated peasant revolution in Russia remained ambivalent; to a certain degree he feared its occurrence, suspecting that it could take on an "Asiatic" hue.[1]

Civil society

Hungarian scholar László Tüto has argued that Marx believed that the bourgeois revolutions meant the worldwide historical liberation of the individual from the hierarchies of traditional societies. However, this liberation carried its own price. On the one hand, civil society and the state separated from each other in the bourgeois system, and as a result the individual became intrinsically split into a private person and a citizen of a state, two forms of existence that became opposed to each other. On the other hand, the economic freedom of private persons as members of civil society could only survive in the service of the spontaneous mechanisms of the market, that is, if people made themselves the tools of the tangible powers of the economy: goods, money, and capital. After the decline of freely competitive capitalism (into monopoly capitalism) this economic freedom was pushed into the background because of the property hierarchies. Freely competitive capitalism was characterized by the basic tendency of revolutionizing the means of production, and Marx concluded that the continuation of this tendency could only be ensured by going beyond the capitalist system to a socialist environment for civil society.

Dictatorship of the proletariat

The "dictatorship of the proletariat" was introduced by Marx and Engels, and later used by V. I. Lenin and Joseph Stalin to justify their totalitarian rule. They controlled the Communist party in the Soviet Union in the name of the proletariat (which had no voice.) Marx and Engels believed in the need for such a dictatorship during the transition to communism following the takeover by the proletariat. They envisaged some undefined form of absolute sovereignty of the people in a radical democratic state based on universal and equal suffrage. Supposedly the dictatorship would allow the proletariat to abolish bureaucracy and private ownership of the means of production, using force and repressive or dictatorial methods to overcome the inevitable resistance by the bourgeoisie. Lenin, however, saw the concept in terms of a dictatorship exercised not by a democratically chosen majority but by a vanguard minority revolutionary party; he eventually accepted the need for a state bureaucracy, and his more extreme opposition to the bourgeoisie led him to favor their exclusion and disenfranchisement to the benefit of the urban working class.

Alienation

Marx's theory of alienation was often employed to criticize religious, political, and economic divisions. However, the fact that it was basically about individuals and could only with great difficulty be applied to society made it a misleading tool when used in sociology.

Globalization

The Communist Manifesto was expressed in terms the 21st century calls globalization. It argued that it was the "historic mission" of the capitalist bourgeoisie to establish markets throughout the world and that four lessons could be drawn from this fact: members of the proletariat do not share the same nationality as the bourgeoisie, the proletarian "globalization" will in fact supercede that of the bourgeoisie, exploitation and class warfare will destroy the national barriers between members of the proletariat, and the proletariat has a duty to overthrow the ruling classes in each nation.

Quotations

- "Every opinion based on scientific criticism I welcome. As to prejudices of so-called public opinion, to which I have never made concessions, now as aforetime the maxim of the great Florentine is mine:

- “Segui il tuo corso, e lascia dir le genti.” Follow your own course, and let people talk – paraphrased from Dante" Karl Marx London, July 25, 1867.

- "From the viewpoint of pure economic theory, Karl Marx can be regarded as a minor post-Ricardian". Paul Samuelson, The American Economic Review, March 1962, pp. 12-15

Bibliography

- Avineri, Shlomo. The Social and Political Thought of Karl Marx (1970) excerpt and text search

- Carver, Terrel, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Marx. 1992. 357 pp. excerpt and text search

- Cohen, Gerald Allen, and G. A. Cohen. Karl Marx's Theory of History (2000) excerpt and text search

- Elster, Jon. Making Sense of Marx. 1985. 556 pp. excerpt and text search

- Elster, Jon. An Introduction to Karl Marx (1986) excerpt and text search

- Hobsbawm, Eric J., ed. Marxism in Marx's Day. 1982. 349 pp.

- Kolakowski, Leszek. Main Currents of Marxism: The Founders, the Golden Age, the Breakdown. (1981, 2005). 1504 pp. covers Marx and all the Marxists excerpt and text search

- McLellan, David. Karl Marx: A Biography (4th ed. 2006)

- Mehring, Franz. Marx: The Story of His Life (1918) online edition another online edition

- Oakley, Allen. Marx's Critique of Political Economy: Intellectual Sources and Evolution. Vol. 1: 1844-1860. Vol. 2: 1861 to 1863. (1984-85). 266pp, 342 pp.

- Rader, Melvin Miller. Marx's Interpretation of History. 1979. 242 pp.

- White, James D. Karl Marx and the Intellectual Origins of Dialectical Materialism. 1996. 416 pp.

Primary sources

- The Portable Karl Marx edited by Eugene Kamenka (1983) excerpt and text search

- Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto (1988) excerpt and text search

- Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto (1848) excerpt and text search

- Marx, Karl. Karl Marx: The Essential Writings ed by Frederic L. Bender. (2nd ed. 1986) 516 pgs. online edition

- Marx, Karl. Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy ed. by Martin Nicolaus (1993) excerpt and text search

- Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (1906), 865pp online ediition

- Marx, Karl. Das Kapital - Kritik der Politschen Ökonomie. 1867. First English edition of 1887 from 4th German edition; edited by Frederick Engels