John Franklin

Rear Admiral Sir John Franklin FRGS (April 15, 1786 - June 11, 1847) was a British sea captain and Arctic explorer whose final expedition disappeared while attempting to chart and navigate the Northwest Passage in the Canadian Arctic. The entire crew was lost and its fate remained a mystery for 14 years; even today his ships have never been found, and the ultimate fate of the last survivors is largely unknown.

Early Career

Franklin was born in Spilsby, Lincolnshire in 1786 and educated at King Edward VI Grammar School, Louth. He was the ninth of 12 children of a family which had prospered in trade. One of his sisters became the mother of Emily Tennyson (wife of the Lord Tennyson).

Although his father initially opposed him, Franklin was determined to have a career at sea. Reluctantly, his father allowed him to go on a trial voyage with a merchant ship. This hardened young Franklin's resolve, so at the age of 14, his father secured a Royal Navy appointment on HMS Polyphemus. Franklin was later present at the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801. Following this he went on an expedition to explore the coast of Australia on the HMS Investigator with his uncle, Captain Matthew Flinders. Following that expedition, he returned to the Napoleonic Wars, serving aboard HMS Bellerophon at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. In 1815, he was at the Battle of New Orleans.

First Expedition

Franklin first travelled to the Arctic in 1818, as a lieutenant under the command of David Buchan, aboard the ships Dorothea and Trent. Their mission was to forge a direct way north beyond Henry Hudson's old record of 80 degrees of latitude. The most optimistic of those who saw them off was Second Secretary of the Admirality Sir John Barrow who, influenced in part by whaler William Scoreseby's reports of unusually large areas of open water and melting ice the year before, believed that this was an ideal time to search for the long-sought (but ultimately chimerical) Open Polar Sea. Buchan and Franklin's ships, unfortunately, met with heavy, gale-driven sea ice just north of the Spitzbergen Islands, and after making emergency repairs were forced to head home. For Franklin, it was his first taste of Arctic adventure, and the fascination was to prove a life-long one. Despite its limited success, the expedition was celebrated in the press, and depicted in an enormous Panoramic painting by Henry Aston Barker at his establishment in Leicester Square in London. At the Admiralty, Sir John Barrow was sufficiently impressed that he recommended Franklin for a further command, and his career as as Arctic explorer was launched.

Second Expedition

Franklin's second expedition, and the first under his direct command, was sent overland via the Great Slave Lake and the Coppermine River in 1819-1822 to explore the shores of the "Polar Sea." Disputes with the Hudson's Bay Company and the North-West Company over supplies led to delays, and several of the men under Franklin's command quit before the final departure. In the end, only Franklin and three other officers (surgeon-naturalist John Richardson and midshipmen George Back and Robert Hood), and one lone enlisted seaman, John Hepburn set off with a company of hired voyageurs and a party of guides from the Dene tribe. They established an outpost, dubbed Fort Enterprise, near the northern tree-line, and spent their first winter there in two wooden structures -- onefor the officers, one for the voyageurs and Hepdurn -- built by cutting down most of the few trees of any size. The following season, Franklin and his men embarked down the Coppermine River.

The expedition proved to be a disaster. While he did reach the northern coast and explored a small part of it, his decision to attempt a short-cut over land rather than via the river they had descended proved very nearly fatal. After having been hauled over the rough terrain, all of the expedition's canoes were soon damaged beyond repair (in frustration, the hired voyageurs apparently broke one deliberately) and the limited supplies of food were soon exhausted. A river crossing forced on the party due to its lack of canoes nearly killed two men with hypothermia, and the only food available was a combination of dessicated deer carcasses and lichens (tripe de roche) pried from rocks. As winter set in, many of the men fell behind, and Franklin sent Back ahead to seek contact with the Dene. The men in the rear quickly succumbed to exposure, and Franklin, in the lead, left Richardson behind with Hood, Hepburn, and Michel Terrehaute, a Mohawk guide. After Michel left this group on several occasions, returning with what he called "wolf meat," Richardson began to suspect cannibalism. Soon after this, Hood was found shot by their campfire; Michel claimed Hood had been cleaning his rifle, but Richardson saw that the bullet had entered from behind. Waiting for an opportunity, he summarily shot Michel for suspected cannibalism and murder. When he and Hepburn reached Fort Enterprise, they found Franklin and the men who had arrived with him close to starvation. They managed to get by for another few days on pounded bone and bits of singed deer-skin, but certainly would all have perished if it were not for the timely return of Back, who brought with him Dene guides and food. Although there is no mention of footwear per se having been eaten, singed and boiled leather was resorted to on many occasions; on his return, this earned Franklin the sobriquet of "the man who ate his boots," and actually helped secure his lasting fame. Despite his misjudgments, he and his men were never charged with any offence, and were indeed hailed are heroes, and Franklin's narrative, Journey to the Shoes of the Polar Sea, became a bestseller.

Marriage, and third expedition

After returning to England, Franklin renewed his acquaintance with the poet Eleanor Porden, whom he had first met in 1818; they were married in 1823. They were a strange match, Franklin with his devout habits who would not attend entertainments on a Sunday, and Eleanor with her lively, independent spirit, but their short time together seems to have been a happy one. In 1824 their daughter, Eleanor Isabella, was born, but her mother's health, never very robust, was seriously compromised. Eleanor died of tuberculosis in 1825, shortly after persuading her husband not to let her ill-health prevent him from setting off on another expedition to the Arctic; Franklin did not receive the news until he arrived at his first outpost. This expedition, a voyage down the Mackenzie River to further explore the shores of the "Polar Sea", was better supplied and more successful than his last. Specially-built boats with stronger hulls performed better than had the voyageurs' canoes, and with them Franklin and Dr. Richardson, who led two separate parties from the mouth of the Mackenzie, explored hundreds of miles of previously uncharted coastline.

Governor of Tasmania

In 1828, Franklin was knighted by George IV and in the same year married Jane Griffin, a close friend of his first wife's, and seasoned traveller in her own right. Jane proved both devoted and indomitable in the course of their life together, and in many ways was a larger public figure than her husband. After making the usual discreet inquiries as to what sort of preferments might be available to a man of his accomplishment, Franklin accepted an appointment as Governor of Tasmania in 1836. He and Jane sailed to Hobart Town shortly after, and took up residence in the Governor's House. Franklin, endeavoring to establish himself as an emissary of enightenment, attempted a number of reforms to the organization of the colony which upset some of its residents, most particularly his own Colonial Secretary George Arthur, who repeatedly sought to undermine his authority. Arthur and his supporters resented Franklin's attempts to reform the penal colony, and took special umbrage at what they saw as too large a role in public affairs taken by Lady Jane Franklin. By a series of behind-the-scenes maneuvers, Arthur managed to have Franklin recalled from his post, but after his departure, he remained popular among many of the people of Tasmania, who, upon his death, erected a statue of him in Franklin Square, Hobart.

Final expedition

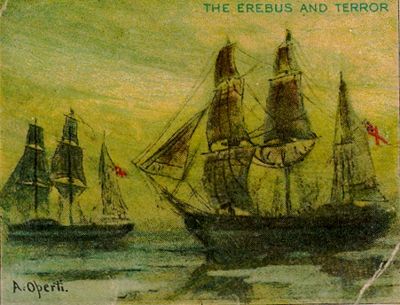

The continued charting of the Arctic coastal mainland in the years following Franklin's third Arctic expedition left less than 500 km of Arctic coastline yet to be explored. At the renewed urging of Sir John Barrow, one further large, heavily-equipped Arctic expedition was decided upon to at last conquer the elusive Northwest Passage. Franklin was eager to lead the expedition, but the Admiralty first offered the post to James Clark Ross. Ross demurred, and the other "Arctic men" called upon for their opinions all supported Franklin; as Parry put it, the man would "die of disappointment" if he were not offered the command. The orders was given signed on February 7,[1845. As second-in-command, the Admiralty selected Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier, a veteran of numerous Arctic expeditions. Yet in an unusual move, the third in command, James Fitzjames, was given the privilege of selecting the subordinate officers; it has been suggested that this was due to Fitzjames's being the best friend of Barrow's son. As a result, experienced Arctic officers were scarce at the lower ranks; many of them, like Fitzjames, had only shortly returned from service in China. The expedition, with 133 men, set sail from Greenhithe on the Thames on May 19, 1845, in two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror (four of the crew were sent back from Greenland as "unfit for service", so the final complement of the expedition was 129).

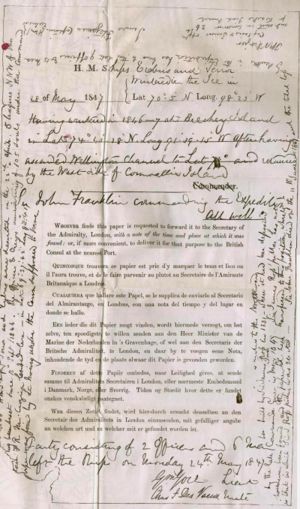

The ships were sturdily built, and had been outfitted with steam heating for the comfort of the crew, large amounts of reading and educational material, and three years' worth of preserved food supplies. Converted railway engines served to turn two screw propellors, though these were only expected to be used occasionally. They were last seen by whalers at Baffin Bay on July 26. The remainder of their route can be reconstructed from the evidence found years later; after entering Lancaster Sound, they proceeded through Barrow Strait, and managed to circumnavigate Cornwallis Island. Fresh from this achievement, they wintered in a protected cove at Beechey Island, where they left signs that an observatory, a forge, and even a garden, had been established on the shore.

The Franklin Search

After two years and no word from the expedition, Lady Jane Franklin, his wife, urged the Admiralty to send a search party. The alarm was slow to grow, however; since the crew carried supplies for three years, the Admiralty waited another year before launching the search and offering a £20,000 reward for success. Not only was this a huge sum for the time, but Franklin's disappearance had captured the popular imagination. At one point, there were 10 British and two American ships headed for the Arctic. (More ships and men were lost looking for Franklin than in the expedition). Ballads telling of Franklin and his fate became popular. The ballad Lady Franklin's Lament commemorated Lady Franklin's search for her lost husband.

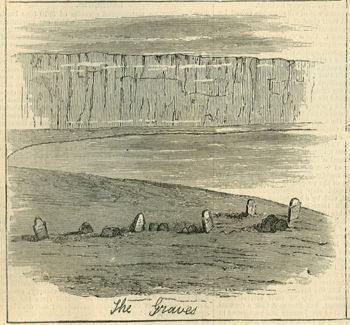

In the summer of 1850, several of the ships converged on Beechey Island, in Wellington Channel, where the first relics of the Franklin expedition were found: a winter encampment with the remains of an observatory, a smithy, an attempt at a garden, and -- most ominously -- the graves of three of Franklin's sailors who had died from natural causes in the winter of 1845-46. Despite extensive searching, no messages were found to have been left there by the Franklin party to provide any indication of his progress or intentions. The bodies of the sailors had been preserved in the frozen ground, and autopsies conducted when the bodies were exhumed in the mid-1980's found that tuberculosis was the most immediate cause of death, though there was also toxicological evidence of lead poisoning.

In 1852, the Admiralty sent a squadron of five ships under the command of Sir Edward Belcher. His ships did not manage to penetrate very far into the icy channels, and after the winter of 1853-53 four of his vessels remained completely ice-bound. The inexperienced Belcher, believing that there was no hope of extracating them from the ice, ordered the ships abandoned, and their crews returned home on HMS North Star, the only ship not trapped in the pack. He was [[court martial}court-martialled]] on his return to England, and though acquitted, never again saw active service. He suffered additional embarassment when HMS Resolute, one of the ships he'd abandoned managed to slip its ice-moorings on its own, drifting crewless as far as the southern end of the Davis Strait where it was found and piloted back to harbor by an American whaling captain. The Belcher expedition was to be the last Franklin search mounted by the Admiralty; declaring that Franklin and his men were presumed to have died in service, they struck the "Erebus" and "Terror" from the lists.

In 1854, Dr. John Rae discovered further evidence of the Franklin party's fate. Rae was not searching for Franklin at all, but rather surveying the Boothia Peninsula on behalf of the Hudson's Bay Company. On this journey, Rae met an Inuk who told him of a party of 35 to 40 white men who had died of starvation near the mouth of the Back River. The Inuit also showed him many objects that were identifiable as having belonged to Franklin and his men.

Lady Franklin commissioned one more expedition under Francis Leopold McClintock to investigate Rae's report. In the summer of 1859, the McClintock party found a document in a cairn on King William Island left by Franklin's second-in-command, giving the date of Franklin's death. The message, dated April 25, 1848, also reported that the ships had been trapped in the ice, that many others had died, and that the survivors had abandoned the ships and headed south towards the Back River. McClintock also found several bodies and an astonishing amount of abandoned equipment, and heard more details from the Inuit about the expedition's disastrous end.

There are several things that contributed to the loss of the Franklin expedition. Like most men of his generation and training, Franklin was culturally conservative, observing wasteful rituals in inappropriate locales; for example, he and his men carried silver plate, crystal decanters, and many extraneous personal effects with them. They attempted to haul much of this heavy gear along with them even after abandoning the ships. They were unwilling or unable to learn survival techniques from the Inuit. Moreover, their expedition was a naval one, not equipped for hiking over land, so none of the sailors had thick boots or jackets. Their ships were locked in the ice for two winters running as a result of a colder period that did not allow the icebound passages to melt in the summer of 1846. The party's morale and cohesion was damaged by psychological effects of lead poisoning from the solder that sealed their tinned food supply. This has been confirmed by lead found in both skeletal and soft tissue remains of expedition sailors conducted by Dr Owen Beattie of the University of Alberta. They also were weakened by internal bleeding from scurvy after the first two years when the preventive lemon juice they carried lost its potency. The Inuit witnesses had reported that crew members exhibited the blackened gums and bruised skin typical of that disease.

Skeletal remains examined by Dr. Anne Keenleyside showed evidence of cut marks found on bones from some of the crew, which strongly suggests conditions were so dire that some resorted to cannibalism. In the end, it was likely a combination of poor planning, bad weather, poisoned food, and ultimately starvation that killed them.

Nevertheless, in his day, Franklin was almost universally regarded as a hero, and the fact that he died in a gallant, and possibly foolhardy attempt to complete his discovery of the Northwest Passage only increased his standing in the eyes of the public. The mystery still surrounding Franklin's last expedition was the subject of a 2006 episode of NOVA, Arctic Passage:Prisoners of the Ice.

Later Searches for Franklin

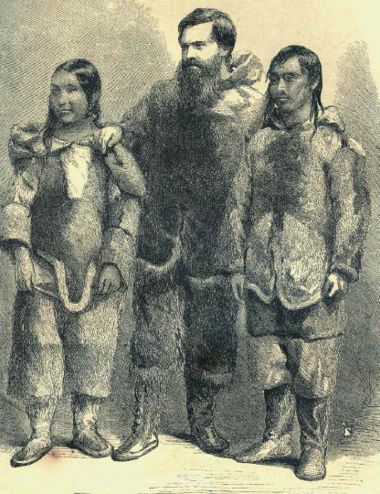

Long after Leopold McClinock declared that the fate of Franklin had been ascertained, searches for evidence have continued; despite the evidence of the Victory Point record, such a large number of issues remain unresolved that Franklin scholars and searchers have continued their activities to the present day. The first of these, by rights, was Charles Francis Hall, a Cincinnatti newspaperman who abruptly left home and hearth to spend years searching for word of Franklin's whereabouts among the Inuit peoples of the Eastern Canadian Arctic in 1860. Hall, aided by his Inuit guides Ebierbing and Tookoolito, interviewed hundred of Inuit and copied down their testimony into his field notebooks.

This testimony is preserved in the Hall Papers at the Smithsonian Insititution's Museum of American History, which provide the largest and most encompassing body of accounts by Inuit eyewitnesses. The accounts confirm the earlier stories of cannibalism told to Dr. John Rae, and describe several encounters with the last survivors of Franklin's men. At one of these, on the southern coast of King William Island near what is now Washington Bay, a band of Inuit hunters met with about 30 survivors, who were dragging a boat over land on a sledge. The leader of these men was known as "Aglooka" -- which, in the Inuit language means "long strides," and the man accompanying him was referred to as "Doktook" (probably an attempt to pronounce "Doctor"). The Inuit traded some seal meat for a knife, and reported that the men, who looked to be starving, cooked the seal meat immediately and ate it. Concerned that they would be unable to support such a large body of hungry people who were unable to hunt for themselves, the Inuit hunters departed early the next morning.

Despite his conviction that some few of the men might have survived -- Hall himself was convinced that "Aglooka" was Francis Crozier -- he was never able to locate any survivors, and after two lengthy sojourns in the Arctic, gave up on his search, turning his attention to the North Pole. The next major Franklin searcher was Frederick Schwatka, an officer in the U.S. Army, who in 1878-1880 led an overland expedition which included Hall's old guide Ebierbing. They wintered on King William Island, and conducted the first summer search of the area, which enabled them to find artifacts that had been missed before; they located the remains of Lieutenant John Irving, and brought them back for later interment in Britain, along with a vareity of personal items such as coins, medallions, buttons, and bits of cloth. It was Schwatka who, after following what he believed to be the route of the last survivors, came upon what he called "Starvation Cove" on the Adeleide Peninsula; here, it seemed, the last men had died, leaving behind only a few scattered items including a leather boot. Ebierbing conjectured that the tide, and the mud (which was quite deep in the summer), had taken the rest.

Although no large-scale searches were mounted after Schwatka's, many who traveled through the eastern Canadian Arctic continued to look for relics over the years. When Knud Rasmussen, camping on King William Island in 1923, asked after Franklin, and old man named Iggiararjuk told him the same story of the Washington Bay encounter that Hall had heard -- and no wonder, as the man who had told it to Hall was Iggiararjuk's own father, Mangaq. In the latter part of the twentieth century, a number of smaller expeditions were undertaken to search for additional clues as to what caused the Expedition's collapse. In 1983 and 1985, Canadian anthropologist Owen Beattie exhumed the bodies of the Franklin sailors buried at Beechey Island, and autopsies were conducted. While the autopsies initialy revealed tuberculosis as the most likely and immediate cause of death, pathology tests conducted on hair and tissue samples showed elevated levels of lead, which Beattie traced to the poorly-applied beads of solder on the cans supplied to the expedition. A few years after Beattie, a second group of anthropologists, led by Dr. Anne Keenleyside, visited a site near that of the whaleboat found by McClintock in 1859, and recovered human skeletal remains of eleven individuals. Tests on these showed wide variations in lead levels, but at least some of the individual men had bone lead levels so high that they would have been suffering from acute lead poisoning. Cut-marks on many of the bones' surfaces also corroborated Inuit accounts of cannibalism among Franklin's Men.

Throughout the 1990's and into the early 2000's David C. Woodman, author of Unravelling the Franklin Mystery: Inuit Testimony, made numerous trips to the vicinity of King William Island in search of clues, using Inuit testimony recorded by Hall. He was particularly interested in a story of a buried cache of records mentioned by one Inuk, but the hard rock scree of King William Island proved to be a very difficult field to search. In a second series of searches, the Utjulik expeditions, Woodman searched the area west of the Adelaide Peninsula using sledge-drawn magnetometers. He hoped the ships' large engines, taken from early British railways, might show up on a magnetic survey. The best targets identified were revisited, holes drilled in the ice, and side-scan sonar booms lowered, but none of the magnetic targets turned out to be the ships' engines.

Literary works inspired by Franklin

From the moment of his disappearance on his final expedition, the mystery and tragedy surrounding Franklin's voyage stirred poets, balladeers, and novelists to their own expressions of loss and elegy.

The mid 1850's saw three book-length works in verse, Abrahall, Chandos Hoskyns Abrahall's Arctic enterprise A poem (1856), James Parsons' Reflections on the mysterious fate of Sir John Franklin (1857), and Joseph Addison Turner's The Discovery of Sir John Franklin, and other poems (1858). In 1860, with the discovery of the final note at Victory Point, several instututions, among them Oxford University, held contests for the best poetic elegy. The Oxford contest was won by a Canadian undergraduate, Owen Alexander Vidal, for his "A Poem upon the life and character of Sir John Franklin," which modern readers find almost unreadably wretched; far better was a poem which did not win, Algernon Charles Swinburne's The Death of Sir John Franklin. Franklin then faded as a subject of poetry for a century, re-emerging in 1960 in Canadian poet Gwendolyn MacEwen's Erebus and Terror, originally written for CBC radio. The most notable recent poetic treatment of Franklin has been David Solway's Franklin's Passage (2003), which was awarded the 36th annual Grand Prix du Livre by the City of Montréal, a first for an Anglophone writer.

Charles Dickens was greatly enamored of Franklin's achievements, and it was at his suggestion and with his support that Wilkie Collins undertook a play, The Frozen Deep, which appeared in 1857 to tremendous acclaim. Originally staged in Dickens's home, it later received a command performance before Queen Victoria, as well as a series of performances in Manchester. Dickens also wrote a long prose essay, "The Lost Arctic Voyagers," which commemorated Franklin's achievement and defended him against his detractors. Henry David Thoreau, though he dismissed Franklin's achievements and urged his readers to seek their own internal "higher latitudes", followed the Franklin story closely, and Joseph Conrad, in his essay "Geography and Some Explorers," credited Franklin's story with inspiring both his career as a seaman and as a novelist. Writing of Sir Leopold McClintock's narrative of his discovery of the fate of Franklin, Conrad recalled:

- "There could hardly have been imagined a better book for letting in the breath of the stern romance of polar exploration into the existence of a boy whose knowledge of the poles of the earth had been till then of an abstract, formal kind, as the imaginary ends of the imaginary axis upon which the earth turns. The great spirit of the realities of the story sent me off on the romantic explorations of my inner self; to the discovery of the taste for poring over land and sea maps; revealed to me the existence of a latent devotion to geography which interfered with my devotion (such as it was) to my other school work."

Although alluded to briefly in Conrad's Heart of Darkness, Franklin did not emerge full-fledged info fiction until later in the twentieth century. Remarkably, since 1965 there have been no fewer than a dozen novels based on his expedition. Beginning with Australian novelist Nancy Catto's North-West by South, we then have Caroline Tapley's John come down the backstay (1974), Sten Nadolny's The Discovery of Slowness (Die Entdeckung der Langsamkeit) (1983), Martyn Godfrey's Mystery in the frozen lands (1988), Mordecai Richler's Solomon Gursky Was Here (1990), William T. Vollmann's The Rifles (1994), Rudy Wiebe's A DIscovery of Strangers (1994), Robert Edric's The Broken Lands (2002), John Wilson's Across Frozen Seas (1997) and North With Franklin: The Journals of James Fitzjames (1999), Elizabeth McGregor's The Ice Child (2001), and Dan Simmons' Terror (2007).

Franklin in popular culture

- The 1981 song Northwest Passage by Stan Rogers makes reference to John Franklin.

- The ballad Lady Franklin's Lament, aka Lord Franklin, has been recorded by numerous artists, including Martin Carthy, Pentangle, Sinéad O'Connor, and the Pearlfishers. The melody was also used for Bob Dylan's song Bob Dylan's Dream, as well as David Wilcox's Jamie's Secret, the latter a song about a young woman who is lost in the frozen foothills of the North Cascades mountains.

- The song I'm Already There on the Fairport Convention album Over the Next Hill is sung from the point of view of a member of one of Franklin's Expeditions.

- The song "900," the B-side to the Breeders' 1993 Cannonball single, has lyrics based on the Franklin expedition, particularly referencing the unnecessary luggage they carried south.

- A remarkable number of people were named after Sir John Franklin, including the Canadian comic John Franklin Candy and the mystery novelist John Franklin Bardin.

List of Franklin search expeditions

- 1848–1849, James Clark Ross in Investigator and Enterprise

- 1848–1851, John Richardson and John Rae overland expedition

- 1848–1851, Plover and Herald via Bering Strait

- 1849 William Penney (Captain) John Anstruther Goodsir (naturalist) in whaling vessel Advice

- 1850–1854, Robert McClure in Investigator via Bering Strait

- 1850–1855, Richard Collinson in Enterprise via Bering Strait

- 1850–1851, William Penny in Lady Franklin and Sophia

- 1850–1851, Horatio T. Austin in four-ship Royal Navy expedition

- 1850–1851, Sir John Ross in private expedition

- 1850, Charles Codrington Forsyth in Prince Albert, financed by Lady Franklin

- 1850–1851, Edwin J. De Haven in first Grinnell expedition

- 1851–1852, William Kennedy and Joseph René Bellot in Prince Albert, financed by Lady Franklin

- 1852–1854, Sir Edward Belcher in a five-ship Royal Navy expedition

- 1852, Edward Augustus Inglefield in Isabel, financed by Lady Franklin

- 1853–1855, Elisha Kent Kane in second Grinnell expedition

- 1853–1854, John Rae on behalf of the Hudson Bay Company

- 1857–1859, Francis Leopold McClintock in Fox, financed by Lady Franklin

- 1864–1869, Charles Francis Hall

- 1875, Allen Young in Pandora, in a private expedition

- 1876, Allen Young in Pandora, in a second private expedition which also took despatches to the expedition of Sir George Nares for the Admiralty

- 1878–1880, Frederick Schwatka, sponsored by the American Geographical Society

See also

Bibliography

- Sir John Franklin's Last Expedition, by Richard J. Cyriax (1939; repr. 1997) ISBN 952739410 is the standard work in the field.

- Captain Francis Crozier: Last Man Standing?, by Michael Smith. Collins Press, 2006. ISBN 1905172095

- Unravelling the Franklin Mystery: Inuit Testimony, by David C. Woodman. McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992. ISBN 0773509364

- Frozen In Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition, by Owen Beattie and John Geiger.

- The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole, 1818-1909, by Pierre Berton. ISBN 0385658451

- "The Type and Number of Expeditions in the Franklin Search 1847–1859," by W. Gillies Ross. Arctic, Vol.. 55, No.. 1 (March 2002) pp. 57–69.

- "The Final Days of the Franklin Expedition: New Skeletal Evidence," by Anne Keenleyside, Margaret Bertulli and Henry C. Fricke. Arctic Vol.50, No. 1 (March 1997) pp. 36 to 46.

- '"Franklin Saga Deaths: A Mystery Solved?" National Geographic Magazine, Vol 178, No 3, Sept. 1990

- The Artic Fox - Francis Leopold McClintock, Discoverer of the fate of Franklin, David Murray, 2004. Collins Press, ISBN 1550025236

- Resolute: The Epic Search for the Northwest Passage and John Franklin, and the Discovery of the Queen’s Ghost Ship, by Martin Sandler (Sterling, 2007) ISBN 1402740859

- NOVA Arctic Passage (DVD of TV documentary) ASIN B000EOTE8G

- Revealed: The Lost Expedition, a documentary produced by John Murray for Channel 5 (UK)

External links

- NOVA's companion website for Arctic Passage

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- The Fate of Franklin (Russell Potter)

- The Life and Times of Sir John Franklin

- Works by John Franklin at Project Gutenberg

- Algernon Charles Swinburne's The Death of Sir John Franklin (complete online text)