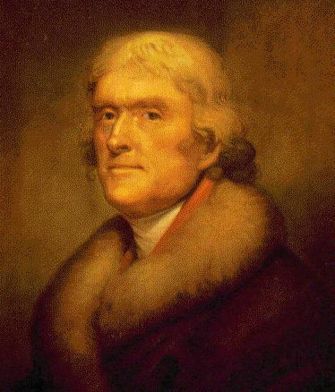

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) was a primary proponent of democracy in world history and a key Founding Father of the United States. He was the primary author of the U.S. Declaration of Independence (1776), the first Secretary of State (1789–1793), and the founder of one of the world's two first political parties, the Democratic-Republican Party. As president (1801–1809), Jefferson purchased the Louisiana Territory in 1803. He is best known as political theorist who helped redefine republicanism and promoted democracy and equal rights, while fighting aristocracy and established religion. Extraordinarily, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams both died on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Early career

Jefferson was the third child born to a well-connected planter family of moderate wealth in Goochland County on Virginia's western frontier. His father, Peter Jefferson (1707-57), of Welsh descent, was a county magistrate and was elected to the House of Burgesses (the legislature). His mother, Jane Randolph, belonged to the leading family in the British colony. Peter taught the boy farming; they hunted and fished together. His formal education began under two Anglican ministers, which was the established church in Virginia. He became proficient in Latin and Greek and had some French. He was also tutored in dancing, became proficient on the violin, learned chess, avoided cards, and was a fearless and accomplished horseman. His father died in 1757, leaving him some slaves and 2,750 acres of undeveloped farmland.[1]

Jefferson was well educated at William and Mary College (class of 1762), and studied law. He was a polymath who read voraciously in history, politics, philosophy, linguistics, architecture, and natural science. He studied science with Dr. William Small, who introduce him to the "familiar table" of Gov. Francis Fauquier and to George Wythe, the leading legal expert of the day in Virginia, who directed Jefferson's reading in law. He was a well-disciplined student who ignored the gambling and horse-racing of his peers to immerse himself in science, law, and history. He mastered the common law treatises of Sir Edward Coke, and was admitted to the bar in 1767. He was successful but did not enjoy the tasks and gave up his practice by 1774. However, the lawyerly style reappears in his famous state papers where he acts the advocate pleading a cause and buttressing it with precedents. Jefferson was never a good speaker, but he excelled in learning and industry and in precision and clarity of writing. His written arguments are powerful; his "Declaration of Independence" remains the touchstone for powerful argumentation.

Patriot

Jefferson had absorbed both the latest ideas of the Enlightenment and the precepts of republicanism as taught by the pamphlets of the British "country party", which had long been out of power. Jefferson became committed to the ancient rights of Englishmen possessed by Virginians; he was outraged that Parliament would threaten those rights.

As the storms of the 1770s broke, young Jefferson had never fully exercised his powerful intellect or fluent pen; he was known as a promising lawyer in a land of great lawyers, a successful planter in a slave society, and a lover of books, science, and music. He was a loyal subject of King George III. From 1768 to 1775, Jefferson was a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses for Albemarle. He was in the audience during Patrick Henry's famous speech, "Give Me Liberty, or Give Me Death!"

Congress

In 1773, following the lead of Massachusetts, Jefferson helped establish the Provincial Committee of Correspondence to keep in touch with the other 12 colonies. In 1774, he drew up resolutions that were published by the first Virginia convention as "A Summary View of the Rights of British America."[2] This pamphlet, issued in four editions that year, argued that Parliament had no right to legislate for the colonies and that the British Empire was bound together solely by allegiance to the King. It proved one of the most influential statements of the patriot position and was widely read.

In 1775, Jefferson was elected to the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia. He drafted the resolution rejecting the conciliatory proposals of the British minister, Lord North. He was appointed county lieutenant in September and did not return to Congress until May 1776. He drafted a proposed constitution for the state of Virginia which was adopted in part.

Declaration of Independence

As a delegate to the Continental Congress, he and John Adams of Massachusetts took the lead in pushing for independence. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of the Virginia delegation proposed independence. Congress appointed a committee of five men to draw up a suitable public Declaration. Jefferson was selected to write it because he was a Virginian, a recognized writer, and a zealous committeeman. He incorporated ideas and phrases from many sources to arrive at a consensus statement that all patriots could agree upon. His colleagues Benjamin Franklin and Adams made small changes in his draft text and Congress made more. The finished document, which both declared independence and proclaimed a philosophy of government, was singly and peculiarly Jefferson's.[3]

The opening philosophical section is closely based on George Mason's "Declaration of Rights," a notable summary of current revolutionary philosophy.[4] Mason wrote:

- That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

Jefferson rewrote it:

- We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Jefferson himself did not believe in absolute human equality, and, though he had no fears of revolution, he preferred that the "social compact" be renewed by periodical, peaceful revisions. That government should be based on popular consent and secure the "inalienable" rights of man, among which he included the pursuit of happiness rather than property, that it should be a means to human well-being and not an end in itself, he steadfastly believed. He gave here a matchless expression of his faith.

The charges against King George III, who is singled out because the patriots denied all claims of parliamentary authority, represent an improved version of charges that Jefferson wrote for the preamble of the Virginia constitution of 1776. Relentless in their reiteration, they constitute a statement of the specific grievances of the revolting party, powerfully and persuasively presented at the bar of public opinion.

The Declaration is notable for both its clarity and subtlety of expression, and it abounds in the felicities that are characteristic of Jefferson's best prose.[5] More impassioned than any other of his writings, it is eloquent in its sustained elevation of style and remains his noblest literary monument.

The concepts of natural law, of inviolable rights, and of government by consent were drawn from the republican tradition that stretched back to ancient Rome and was neither new nor distinctively American. However it was unprecedented for a nation to declare that it would be governed by these propositions. It was Jefferson's almost religious commitment to these republican propositions that is the key to his entire life. He was more than the author of this statement of the national purpose: he was a living example of its philosophy, accepting its ideals as the controlling principles of his own life. Congress adopted the Declaration on July 4, 1776, which became the birthday of the independent nation.[6]

When the Declaration was signed, all British forces had been driven out of the 13 colonies, which now became the 13 states. However. King George III refused to give up "his" possessions, so the war dragged on until the final American victory at Yorktown in 1781 caused Parliament to change the government in London and sue for peace.

The Declaration immediately sparked serious discussion in Europe and Latin America about the legitimacy of empires. By the 21st century, over 100 countries had their own declarations of independence, modeled in part on the very first one by Jefferson in 1776.[7]

Reforming Virginia

In September 1776, Jefferson left Philadelphia and spent the rest of the war in Virginia, where he took control of the legislature and had a significant impact in shaping the laws of the new state.[8] In the House of Delegates, he proposed a series of major reforms--almost unparalleled in scope and unequaled as the work of a single legislator. Of 126 bills he proposed, four-fifths were enacted in some form; and Jefferson drew up almost half the total. In 1779 he proposed "The Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom," which was adopted in 1786.[9] Its goal was complete separation of church and state and declared the opinions of men to be beyond the jurisdiction of the civil magistrate. He asserted that the mind is not subject to coercion, that civil rights have no dependence on religious opinions, and that the opinions of men are not the concern of civil government, became one of the American charters of freedom. This elevated declaration of the freedom of the mind was hailed in Europe as "an example of legislative wisdom and liberality never before known."[10]

Jefferson put forth numerous proposals to reform public education, but they failed at this time. He did manage to abolish the professorships of Hebrew, theology, and ancient languages at the College of William and Mary, and instead set up professorships of anatomy and medicine, law, and modern languages, the two latter being the first of their kind in America. His proposals to gradually end slavery were not reported out of committee.

His laws on inheritance ended the practice of primogeniture, whereby the eldest son inherited the entire estate, so as to spread out wealth more evenly and open up opportunities for more young men.

In 1779 he was elected to succeed Patrick Henry as governor of Virginia for a one year term. Everything went wrong. British invasions by land and sea, Indian raids in the west, fiscal shortfalls, militia problems, profiteering, personal rivalries, and the shift of the main theater of war to Virginia created more challenges than he could solve. Re-elected in 1780, he saw the main British army under Cornwallis enter from the South in 1781; the Continental Army commander, General Von Steuben, was outmaneuvered. Jefferson quit office before his successor was named and the legislature had fled; he was almost captured when the British raided Monticello looking for him. Fortunately Washington arrived with the American and French armies and trapped Cornwallis at Yorktown, where the entire British army surrendered. Later the legislature investigated his administration and vindicated him, but Jefferson was embarrassed. Jefferson was an efficient, systematic, indefatigable administrator with a knack for getting men to work together smoothly, but his militia could not match the British army. He coped with these problems with a degree of success or failure that remains controversial among scholars. [11]

He suffered an irreparable loss when his beloved wife Martha died in 1782 and he gave up all idea of ever marrying again; they had three surviving daughters-—Martha (1772–1836), Mary (1778–1804), and Lucy (1782–1784).

Notes on the State of Virginia

In 1780-83, Jefferson wrote his only book, Notes on the State of Virginia.[12] It was written in the form of answers to questions about the geography, natural resources, Indians, government and economy of Virginia, based on his own research. The book was first published in French in Paris in 1785 (and in English in 1787), and immediately Jefferson's scientific reputation in Europe, while debunking some outlandish theories, especially those of the eminent naturalist the Comte de Buffon, to the effect that animals regressed to smaller size in the new world. Jefferson's coup came with the mammoth, the giant extinct animal, five times bigger than an elephant, whose tusks, grinders, and bones had been recently dug up in the western part of the state.[13]

Confederation Congress

In 1783 Jefferson returned to Congress, became its leader, and launched another intensive legislative effort. His major achievement was conceptualizing a solution for territorial government in the land north of the Ohio River. Virginia ceded its land claims to the national government, Jefferson proposed a checkerboard system of land surveys, which avoided the terrible confusion that caused endless lawsuits over land ownership south of the river. One section in every sixteen was set aside to support public schools. Statehood was promised once a territory reached a certain population. Jefferson would not allow slavery in the territories. Many of Jefferson's ideas were passed into law after he left Congress, notably in the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.[14]

Jefferson's report on coinage established the decimal dollar as the unit of money, though he failed then and later to secure a system of uniform weights and measures based on decimal notation.

Minister to France

He succeeded Benjamin Franklin as minister to France (1784-89), and so was not present when the Constitution was written and ratified.[15] However, he kept himself abreast of political developments in the United States through regular correspondence, most notably with James Madison. Jefferson was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary in May of 1784 joining both Franklin and John Adams. There, the three were charged with "concerting draughts or propositions for Treaties of Amity and Commerce with the Commercial Powers of Europe.[16] Not long after, Franklin left for America and Adams to take up his post as Minister to the Court of St. James leaving Jefferson as the sole Minister to the Court of Versailles on the eve of the French Revolution.

1790s

Jefferson returned from France in 1789 and became the first Secretary of State (1789-1793) in the cabinet of President George Washington. With his close ally James Madison (a member of the House) Jefferson opposed the Hamiltonian programs for national finance, especially assumption of state wartime debts and the First National Bank. Jefferson and Madison and created a new party the Republicans, (called the Democratic-Republican Party by historians) to oppose Hamilton's Federalist party. These were the first two modern political parties in the world (that is the first to reach out to the voters for support). Jefferson and his Republicans supported the French Revolution (from 1793 to 1800), while the Federalists favored Britain. President Washington managed to maintain neutrality in the war between Britain and France. Hamilton had more influence than Jefferson, even in foreign policy, as shown by Hamilton's success in securing the Jay Treaty of 1795 that opened ten years of friendly trade with Britain.[17]

Jefferson was defeated for president in the election of 1796 by John Adams, but became Vice President. When the Quasi War (that is undeclared war) with France broke out in 1798 and Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition laws, Jefferson and Madison protested by secretly writing the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798. They argued the right of state governments to nullify federal laws considered unconstitutional; this was the start of the States Rights theory that played a role in the coming of the American Civil War in 1861 and still plays a role in Constitutional debates.[18]

President: Successful first term, 1801-1805

Jefferson defeated Adams and was elected President in 1800, in what his supporters called the Revolution of 1800. In his first term Jefferson negotiated the Louisiana Purchase with France, then sent Lewis and Clark to explore the vast new lands and set up a territorial system for the Louisiana Purchase. He promoted reservations for Indians to settle them on fixed parcels of land and teach them to farm (instead of hunting and raiding).[19]

Jefferson removed many Federalist office holders in order to balance the civil service between parties. Bitterly opposed to strong judges, he had Congress abolish the lower courts the Federalists had created, and tried to impeach and remove two Federalist judges. He succeeded in removing one incompetent figure but was defeated when he tried to remove Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase. Jefferson never dared attack Chief Justice John Marshall, a Federalist who made the Supreme Court a bastion of nationalism, much to Jefferson's disgust.

President: Troubled second term, 1805-1809

Jefferson's second term was marked by escalating tensions with both Britain and France, which were again at war with each other. Jefferson's use of economic coercion, especially the Embargo of 1807, failed, as he tried to crack down on New England merchants who defied laws that restricted their trade. Jefferson's military policy has been often debated among historians. He at times built up the navy and at other times opposed naval expansion, insisting that the militia aided by small gunboats would suffice. Some historians judge his military policies a major disaster, for they failed badly when War of 1812 with Britain came three years after he left office.[20]

Jefferson and slavery

In Notes on the State of Virginia (1785) Jefferson deplored the despotic, lawless treatment of slaves, suggesting that the only remedy was to emancipate and remove Virginia's slaves and then declare them a free and independent people. Colonization to an unspecified destination was necessary because racial co-existence was impossible; emancipation otherwise would produce "convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of one or the other race." Differences between the two races were "fixed in nature", he said:

- "Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me, that in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior...and that in imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous."[21]

Jefferson believed that, eventually, all Americans had to be free. His goals for unlimited national improvement were incompatible with slaves in America. Both slavery and the slave trade would have to be ended in favor of free commerce and free labor. The key word for Jefferson was "amelioration," and it included several stages of national and moral development. First, Americans would abolish the slave trade. "Citizens," President Jefferson declared in 1806, should "withdraw . . . from all further participation in those violations of human rights which have been so long continued on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa" to promote "the morality, the reputation, and the best interests of our country."[22] Second, the owners should raise up the moral and intellectual levels of their slaves. As masters established ties of reciprocal obligation and sympathy with their slaves, they would prepare themselves—and their slaves for the emancipation and repatriation of all Africans back to Africa. He in fact did secure the abolition by Congress of the international slave trade in 1808. He owned slaves--some 200 at one time or another--but despite his theoretical opposition to slavery he was always so much in debt he could never free them.[23]

Helo and Onuf (2003) have explored the logic of Jefferson's philosophical position against slavery in light of his ownership of slaves and his belief that the wholesale and immediate emancipation of slaves would threaten the new Republic. Heavily influenced by the writings of political philosophers Charles de Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, and especially Lord Kames, Jefferson grounded his position regarding slavery on the Kamesian principle that man was capable of moral development and, consequently, moral codes varied among different nations and progressed (or retrograded) over time in each nation. Kames posited that moral progress in a society, however, required a government. These concepts and others helped Jefferson shape his arguments in the Declaration of Independence, as rationale for the American Revolution. Moreover, they were the basis for his belief that slaves should be freed only when they could be assured of having their own government and a means, thereby, of self-determination as well as practical and moral education. Jefferson was convinced that emancipation on a large scale, before Virginia slaveholders and American society as a whole advanced morally, would precipitate racial violence and put the American experiment at risk.[24]

Retirement

In political retirement Jefferson founded the University of Virginia, which he considered a major accomplishment. He believed that republican government depends on an informed citizenry; that education is a duty of the state; and that, while all should be given learning sufficient to enable them to understand their rights and duties as citizens, the "natural aristocracy" of virtue and talent should be drawn forth from the general mass and given every opportunity of public education. He continued through life to advocate this philosophy of education.[25]

Jefferson, a deist, was keenly interested in religion, and always worked to create a "wall of separation" between church and state, fearing that unifying the two would create tyranny over the free minds of people.

Image and memory

Jefferson has been commemorated in the names of many counties and schools. Conservative commentator George Will has called Jefferson the "Man of the Millennium"-- that is, the most influential person in world history over the last 1000 years. The modern Democratic Party claims direct descent from Jefferson (despite a gap in continuity), and the contemporary Republican Party has given Thomas Jefferson credit for many of its principles, such as limiting the size of government and basing the economy on a free market.

Bibliographical essay

- See also: Thomas Jefferson/Bibliography

- Banning, Lance. The Jeffersonian Persuasion: Evolution of a Party Ideology (1978) excerpt and text search

- Bernstein, Richard B. Thomas Jefferson (2005) short biography excerpt and text search

- Channing, Edward. The Jeffersonian System, 1801-1811 (1906) full text online* Cunningham, Noble E. Jr . In Pursuit of Reason: The Life of Thomas Jefferson (1988, short biography) excerpt and text search

- Ellis, Joseph J. American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (1998), interpretive essays excerpt and text search

- Ferling, John. Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800 Oxford University Press, 2004 online edition

- Hofstadter, Richard. The American Political Tradition (1948), chapter on TJ online at ACLS e-books

- Jefferson, Thomas. Writings (1984, Library of America); includes Autobiography, Notes on the State of Virginia, Public and Private Papers, Addresses and Letters. 1600pp excerpt and text search

- Jefferson, Thomas. Political Writings, edited by Joyce Appleby and Terence Ball; Cambridge University Press, 1999 online edition

- Jefferson, Thomas. Jeffersonian Cyclopedia 9000 quotes, well arranged online

- Koch, Adrienne. Philosophy of Thomas Jefferson. (1943) online edition

- Peterson, Merrill D. The Jefferson Image in the American Mind (1960) excerpt and text search

- Peterson, Merrill D. Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography (1986), long, detailed biography by leading scholar; online edition; also excerpt and text search

- Onuf, Peter S. The Mind of Thomas Jefferson. (2007). 281 pp.

- Onuf, P. S. "Jefferson, Thomas (1743–1826)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004; online edn, May 2008; Onuf is a leading American scholar

- Peterson, Merrill D. ed. Thomas Jefferson: A Reference Biography. (1986), very good, encyclopedic essays

- Smelser, Marshall. The Democratic Republic: 1801-1815 (1968) good one-volume history of TJ's presidency and Madison's;

Footnotes

- ↑ Merrill D. Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography (1975), ch. 1.

- ↑ see for text

- ↑ See "Declaration of Independence"

- ↑ see "The Virginia Declaration of Rights," Final Draft,12 June 1776

- ↑ See Carl Becker, The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas (1922), ch. 5, online edition; Garry Wills, Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence (1978); Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (1997).

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975), ch. 2.

- ↑ Historians discount the influence of previous declarations. David Armitage, The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (2007), excerpt and text search.

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975), ch. 3.

- ↑ see text

- ↑ See Richard Price to Sylvanus Urban,, July 26, 1786, in Richard Price, The correspondence of Richard Price, (1991) vol. 2, p. 45 online.

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975) ch. 4

- ↑ See for complete text of Notes on the State of Virginia.

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975) pp 242-52; Thomas O. Jewett, "Thomas Jefferson Paleontologist," Early America Review, Fall 2000 online.

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975), pp.274-285.

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975) ch. 6

- ↑ Library of Congress, American Memory, "United States Congress, May 1784, Instructions to American Foreign Ministers for Negotiating Treaties of Amity and Commerce," http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib000918

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975), ch. 7.

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975), ch. 8.

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975), ch. 9.

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975), ch. 10. This source needs to be checked against the claims of this paragraph.

- ↑ Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia ch 14

- ↑ "Sixth Annual Message," December 2, 1806

- ↑ * Christa Dierksheide, "'The great improvement and civilization of that race': Jefferson and the 'Amelioration' of Slavery, ca. 1770–1826," Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 6#1 Spring 2008, pp. 165-197.

- ↑ Ari Helo and Peter Onuf, "Jefferson, Morality, and the Problem of Slavery." William and Mary Quarterly 2003 60(3): 583-614. Issn: 0043-5597 Fulltext: History Cooperative

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975), ch. 11.