Copperheads

The Copperheads were a faction of Democrats in the North who opposed the American Civil War, wanting an immediate peace settlement with the Confederate States of America. The name Copperheads was given to them by their opponents the Republicans, after a venomous snake. Copperheads reinterpreted this insult as a term of honor, and wore copper liberty-head coins as badges. They were also called "Peace Democrats" and "Butternuts". The most famous Copperhead was Ohio's Clement L. Vallandigham, who was a vehement opponent of President Abraham Lincoln's policies. For many years after the war Republicans ridiculed Democratic politicians for taking support from Copperheads who were treasonous during the war.

Agenda

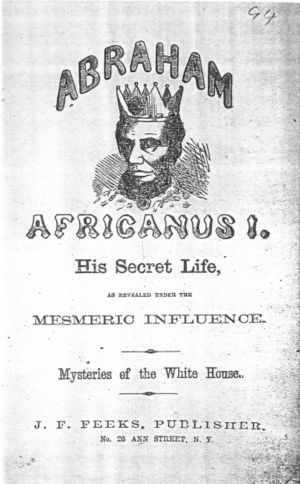

During the Civil War (1861-1865), the Copperheads nominally favored the Union but strongly opposed the war, for which they blamed abolitionists, and they demanded immediate peace and resisted draft laws. They wanted Lincoln and the Republicans ousted from power, seeing the president as a tyrant who was destroying American republican values with his despotic and arbitrary actions.

Some Copperheads tried to persuade Union soldiers to desert, and had some success in southern Illinois. They talked of helping Confederate prisoners of war seize their camps and escape. They sometimes met with Confederate agents and took money. The Confederacy encouraged their activities whenever possible.[1] Most Democratic party leaders, however, repelled Confederate advances.

Some historians, such as Richard Curry, have downplayed the treasonable activities of the Copperheads, arguing that they were traditionalists who fiercely resisted modernization and wanted to return to the old ways.

Newspapers

The Copperheads had numerous important newspapers, but the editors never formed any sort of informal alliance. In Chicago, Wilbur F. Storey made the Chicago Times into Lincoln's most vituperative enemy. The New York Journal of Commerce, originally abolitionist, was sold to owners who became Copperheads, giving them an important voice in the largest city. A typical editor was Edward G. Roddy, owner of the Uniontown, Pennsylvania Genius of Liberty. He was an intensely partisan Democrat who saw blacks as an inferior race and Abraham Lincoln as a despot and dunce. Although he supported the war effort in 1861, he blamed abolitionists for prolonging the war and denounced the government as increasingly despotic. By 1864 he was calling for peace at any price.

John Mullaly's Metropolitan Record was the official Catholic newspaper in New York City. Reflecting Irish opinion, it supported the war until 1863 before becoming a Copperhead organ; the editor was then arrested for draft resistance. Even in an era of extremely partisan journalism, Copperhead newspapers were remarkable for their angry rhetoric. "A large majority [of Copperheads]," declared an Ohio editor, "can see no reason why they should be shot for the benefit of niggers and Abolitionists." If "the despot Lincoln" tried to ram abolition and conscription down the throats of white men, "he would meet with the fate he deserves: hung, shot, or burned."[2]

Copperhead resistance

The Copperheads sometimes talked of violent resistance, and in some cases started to organize. They never actually made an organized attack. As war opponents, Copperheads were suspected of disloyalty, and Lincoln often had their leaders arrested and held for months in military prisons without trial. Probably the largest Copperhead group was the Knights of the Golden Circle; formed in Ohio in the 1850s it became politicized in 1861. It reorganized as the Order of American Knights in 1863, and again, early in 1864, as the Order of the Sons of Liberty, with Clement L. Vallandigham as its commander. One leader, Harrison H. Dodd, advocated violent overthrow of the governments of Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, and Missouri in 1864. Democratic party leaders, and a Federal investigation, thwarted his conspiracy. Indiana Republicans used the sensational revelation of an antiwar Copperhead conspiracy by elements of the Sons of Liberty to discredit Democrats in the 1864 House elections. The military trial of Lambdin P. Milligan and other Sons of Liberty revealed plans to set free the Confederate prisoners held in the state. The culprits were sentenced to hang but the Supreme Court intervened in Ex parte Milligan, saying they should have received civilian trials. [3]

Most Copperheads actively participated in politics. On In May 1863, former Congressman Vallandigham declared that the war was being fought not to save the Union but to free the blacks and enslave Southern whites. The Army then arrested him for declaring sympathy for the enemy. He was court-martialed and sentenced to imprisonment, but Lincoln commuted the sentence to banishment behind Confederate lines. The Democrats nevertheless nominated him for governor of Ohio in 1863; he campaigned from Canada but was defeated after an intense battle. He operated behind the scenes at the 1864 Democratic convention in Chicago; this convention adopted a largely Copperhead platform, but chose a pro-war presidential candidate, George B. McClellan. The contradiction severely weakened the chances to defeat Lincoln's reelection.[4]

Profile of the average member

The sentiments of Copperheads attracted Southerners who had settled north of the Ohio River, social conservatives, poor subsistence farmers, and foes of railroads, banks and monopolies. Copperheads did well in local and state elections in 1862, especially in New York, and won majorities in the legislatures of Illinois and Indiana. Copperheads were most numerous in border areas, including southern parts of Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana (in Missouri, comparable groups were avowed Confederates). The Copperhead coalition included many Irish Catholics in eastern cities, mill towns and mining camps (especially in the Pennsylvania coal fields). They were also numerous in German American Catholic areas of the Midwest, especially Wisconsin.

Historian Kenneth Stampp has captured the Copperhead spirit in his depiction of Congressman Daniel W. Voorhees of Indiana:[5]

There was an earthy quality in Voorhees, "the tall sycamore of the Wabash." On the stump his hot temper, passionate partisanship, and stirring eloquence made an irresistible appeal to the western Democracy. His bitter cries against protective tariffs and national banks, his intense race prejudice, his suspicion of the eastern Yankee, his devotion to personal liberty, his defense of the Constitution and state rights faithfully reflected the views of his constituents. Like other Jacksonian agrarians he resented the political and economic revolution then in progress. Voorhees idealized a way of life which he thought was being destroyed by the current rulers of his country. His bold protests against these dangerous trends made him the idol of the Democracy of the Wabash Valley.