Grand Trunk Railway

The Grand Trunk Railway was a 19th-century Canadian railway system based primarily in Ontario and Quebec with operations over much of Canada and neighboring parts of the United States. It grew rapidly, becoming at one time, the longest railroad in the world. Troubled financially by extending its route to the Pacific Ocean, the railroad was nationalized by the Canadian government in 1923 to form Canadian National Railway. Portions of the Grand Trunk continued to operate under this name in the United States.

Construction

The Grand Trunk Railway was chartered in 1852 to build a railroad between Toronto and Montreal. Construction on the line between Montreal and Toronto started in 1853. By 1855, the section from Montreal to Brockville was complete. In 1856, the sections of the line from Brockville to Toronto and from Toronto to Stratford were complete. By 1859 the line had been extended to Sarnia. The GT was aided in its construction by buying five local railways between Sarnia and Montreal. It also acquired a 999-year lease on the Atlantic & St. Lawrence Railroad that provided access to the ice-free port at Portland, Maine.

Across lower Ontario, traffic grew quickly as the Grand Trunk made connections between Michigan (with access to Chicago and the Western U.S.) and Buffalo, which served as a gateway to eastern markets. The Grand Trunk's early growth was stimulated by the enormous growth of U.S. trade after 1854 caused by Canadian-American reciprocity, which meant free trade between Canada and the U.S.

The London & Ottawa Connections

London financiers were the backers of the line and the railroad was headquartered there. To encourage investment, the Grand Trunk published a prospectus to promote the railway.[1] According to the prospectus, the amalgamated railway would be the most comprehensive system of railway in the world, comprising 1,112 miles from Portland to Lake Huron, and would be built to as high a standard as any in England.

Throughout its life, London financiers funded the Grand Trunk's purchase or lease of 50 other railways, making it by 1869 the world's longest railroad. Despite these bankers and its private ownership, the Grand Trunk quickly became vital to Canada, which became a unified dominion in 1869. The new Canadian government also facilitated the GT's growth with subsidies.

Late 19th Century Growth & Troubles

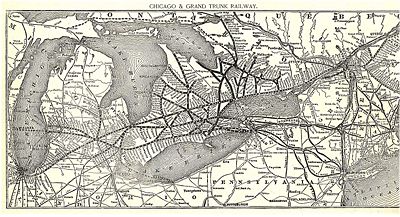

By the 1880s, it reached most major cities in Quebec, crossed into Maine and Vermont, and stretched into the fast-growing Detroit-Chicago corridor inside the U.S. The Grand Trunk bought railroads in Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois to secure a route to Chicago. Apart from a 5-day strike in 1876, it avoided the labor violence that characterized most railways in the late 19th century.

In spite of its backers and the Canadian government, the GT was never profitable because of competition from shipping and American railways. In 1880, for instance, 40% of the Grand Trunk traffic was bridge traffic across the southern tier of Ontario between Port Huron and Buffalo and not bound for any Canadian destination. Inflated construction costs, overestimated revenues, and an inadequate initial capitalization threatened bankruptcy for the Grand Trunk.

Sir Joseph Hickson was a key executive from 1874 to 1890 based in Montreal who kept it afloat financially by allying it with the Conservative Party. Carlos and Lewis (1995) showed that the Grand Trunk managed to survive because its British investors accurately assessed the corporation's value and prospects, which included the likelihood that the Canadian government would bail out the railway should it ever default on its bonds. The government had guaranteed a very large loan and had enacted legislation authorizing debt restructuring. Such arrangements allowed the company to float new bond issues to replace existing debt and to issue securities in lieu of interest.

The Pacific Extension

American executive Charles Melville Hays (1856–1912) joined the Grand Trunk in 1895 as general manager (and in 1909, president, based in Montreal). Hays was the architect of the great expansion during a colorful and free-spending era. He upgraded the tracks, bridges, shops, and rolling stock, but was best known for building huge grain elevators and elaborate tourist hotels such as the Chateau Laurier in Ottawa.

Hays blundered in 1903 by building a subsidiary, the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. This extension was some 4800 km long and built between Winnipeg, Manitoba and Prince Rupert, British Columbia. The extension was completed in 1914 (two years after Hays's death). To connect this extension with the rest of the GT system, the Canadian government built the National Transcontinental Railway which the Grand Trunk operated. The Pacific extension, however, had problems. The very expensive subsidiary was far north of major population centers and had far too little traffic. The cost of constructing the Pacific extension and the meager returns in operating led the GT towards bankruptcy after World War I. Avoiding the possibility of breaking up this transcontinental railroad, the Canadian government nationalized the entire system. In 1923 the government merged the Grand Trunk, the Grand Trunk Pacific, the Canadian Northern, and the National Transcontinental lines into the new Canadian National Railway.

The Remnants of the Grand Trunk

The Grand Trunk name survived on Grand Trunk's former United States lines. In 1928, Canadian National Railways consolidated its lines in Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois into the Grand Trunk Western Railroad, a separate company owned by the CNR. The Portland line also kept the Grand Trunk name until acquired by a shortline operator in 1989.

Notes

- Editable Main Articles with Citable Versions

- CZ Live

- Engineering Workgroup

- History Workgroup

- Business Workgroup

- Railroad History Subgroup

- Business History Subgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- Engineering Content

- History Content

- Business Content

- History tag

- Railroad History tag

- Business History tag