Aisne operations

The Aisne operations were three American military operations on the Western Front in World War I. The second one, the US-French Aisne-Marne operation with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) under General John J. Pershing, July-August 1918, broke the front of the German forces in France and signaled the beginning of the end of World War I.

Aisne Defensive

Aisne Defensive (May 27-June 5, 1918), also known as the Chemin des Dames Offensive. was a sequel to operations on the Somme in March, 1918. This time the Germans made a new attack southward between Soissons and Reims with the intention of drawing French reserves south so that they could renew their attacks in the north. The attack was successful even beyond their hopes, and reached the Marne near Château-Thierry, only forty miles from Paris. The Germans then attempted to establish a bridgehead on the Marne, and also to push westward toward Paris; both efforts were unsuccessful. Two American divisions took part in the defense: the Third, opposing the crossing of the Marne; and the Second, being very heavily engaged at Belleau Wood and at Vaux, west of Château-Thierry.

Aisne-Marne Operation

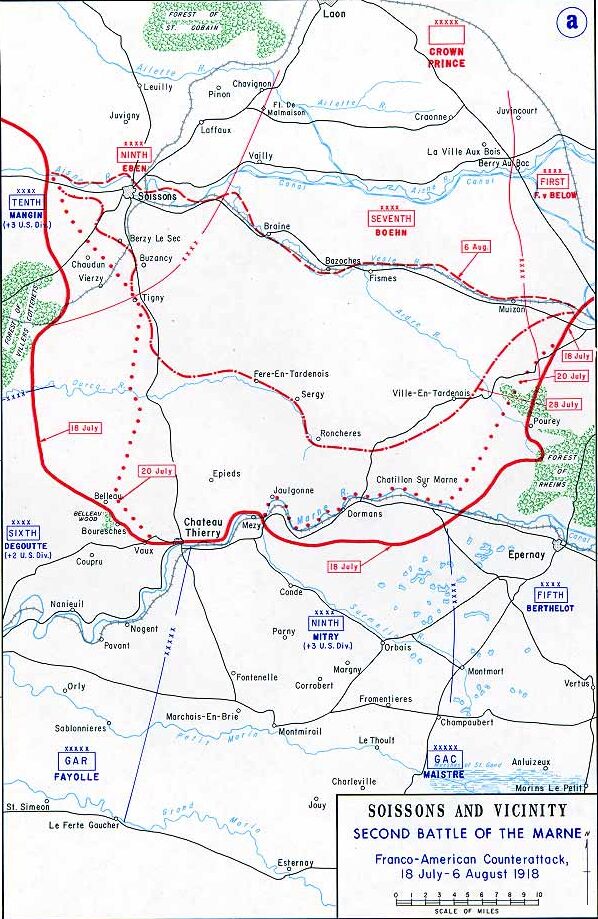

The Aisne-Marne operation (July 18-Aug. 6, 1918), also called the Aisne-Marne Offensive or the Second Battle of the Marne, was the Franco-American counteroffensive following the German offensive of July 15 in the Marne salient.

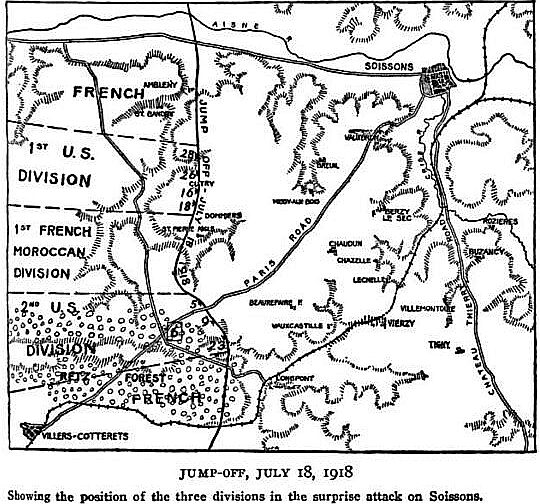

The French Tenth Army (under Gen. Mangin) opened the attack, striking eastward into the salient just south of Soissons. The main attack was made by the XX Corps, with three divisions in front line, two American and one Moroccan. The Germans were taken by surprise, and their outpost line made little resistance, but the line soon stiffened and the fighting was severe. It was not until July 21 that control of the Soissons-Château-Thierry highway was gained. The total penetration was eight miles. The American 36th division earned a reputation for aggressiveness.[1]

From July 21 on, the armies farther east joined in the advance--the Sixth (Degoutte) and the Fifth (Berthelot), along both faces of the salient. With the Sixth Army there were two American corps headquarters--the I (Liggett) and the III (Dickman)--and eight American divisions. The Germans conducted their retreat skillfully, making an especially strong stand on the Ourcq on July 28. But early in August they were back behind the Vesle.

Oisne-Aisne operation

The Oisne-Aisne operation (Aug. 18-Nov. 11, 1918) was a successful Anglo-Fremch operation to exploit the success of the July-August Aisne-Marne operation in reducing the Marne salient, French Gen. Henri Pétain ordered Gen. Jean Marie Degoutte's Sixth Army and Gen. Charles Mangin's Tenth Army to continue their offensive between the Aisne and the Oise. The American Third Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert Lee Bullard, was in Degoutte's army east of Soissons when the attack was resumed. The American Seventy-seventh Division, under generals George B. Duncan, Evan M. Johnson, and Robert Alexander, and the Twenty-eighth Division, under Maj. Gen. Charles H. Muir, were in line, left to right, behind the Vesle River. After indecisive fighting along this stream the two divisions crossed, Sept. 4, with the general French advance, and against strong opposition by German Gen. Von Boehn's Seventh Army, pushed across the watershed toward the Aisne. The Twenty-eighth Division was relieved on Sept. 8; the Seventy-seventh on Sept. 16, after progressing ten kilometers and crossing the Aisne Canal. Placed in line in Mangin's army north of Soissons, the Thirty-second Division attacked toward Juvigny on Aug. 28, which was taken on Aug. 30. On Sept. 2, after repeated attacks, the division reached the National Road at Terny.

Casualties and results

The eight AEF divisions that participated in the reduction of the Aisne-Marne salient suffered some 50,000 casualties in the fighting between 18 July and 6 August. The combat was as close to Pershing’s vision of "open warfare" as anything the Allies had seen in over three years on the Western Front. Pershing, therefore, directed his staff to investigate and report on improved tactics with lower casualties. The study critiqued the tactics that Americans had used, concluding, that as far as the infantry was concerned, there was "almost never any attempt to maneuver, that is, to throw supports and reserves to the flanks for envelopment." Pershing insisted that "the attempt to use trench warfare methods in an open warfare combat will be successful only at great cost." Instead, the study recommended, "where strong resistance is encountered, reinforcements must not be thrown in to make a frontal attack at this point, but must be pushed through gaps created by successful units to attack these strong points in the flank or rear." These tactical concepts were fairly advanced, approximating the most progressive ideas being used in the German Army, as well as by the best British, Canadian and Australian divisions. [2]

The Aisne-Marne operations changed the whole aspect of the war. A German offensive had been stopped suddenly in mid-career, and the advance changed to a retreat. The Marne salient had ceased to exist, and the Germans were never again able to undertake a serious offensive.

Bibliography

- Coffman, Edward M. The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I (1968)

- Grotelueschen, Mark E. Doctrine under Trial: American Artillery Employment in World War I, (2001) online edition

- Smythe, Donald. Pershing: General of the Armies. (1986). 399 pp.

- Thomas, Shipley. The History of the A. E. F. (1920), 540pp; full text online

- White, Lonnie J. "The Combat History of the 36th Division in World War I" Military History of Texas and the Southwest 1982 17(4): 123-179. Issn: 0047-7389