User:David MacQuigg/Sandbox/Email security

Talk: Email security is such a huge topic, we could write a book. What are the most important things we can say to students in just a few pages?

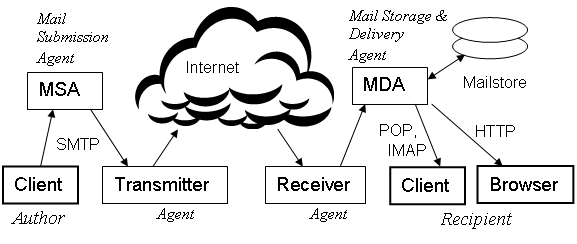

This article on Email security provides a brief overview of the ways in which email systems may be abused, and the most effective ways to fight that abuse. We categorize the vulnerabilities according to their locality in Figure 1 of Email system, repeated here for convenience. We assume the reader is familiar with that article.

In each category, we summarize the requirements for security. These are high-level requirements, not recommendations for any specific method or technique, and not intended as a rigid standard for every system. The same level of security may be provided in some other way. For example, there is less need for passwords if every user can be authenticated by their address on a local network, secure from any outside intruder.

Client vulnerabilities

After running a malicious program, perhaps from a phony website or attached to an email, the user's computer may become infected with a zombie program controlled by a remote criminal system. This can result in stolen passwords and data, access to other computers with confidential data, or malicious transmissions from the user's computer, including spam and additional malicious programs.

Users should be:

1) trained to not run any programs that may infect their computer.

2) required to maintain secure passwords.

3) required to submit emails through their regular MSA, even when they are on the road.

4) required to update their computers whenever a security issue arises.

MSA vulnerabilites

A Mail Submission Agent (MSA) may be tricked into relaying mail from an unauthorized source, or from an authorized source that has been infected or has been compromised in some other way. For example, some large email services, eager to get new accounts, may allow criminals to automate their acquisition of free accounts.

Mail Submission Agents should:

1) authenticate any user attempting to submit an email.

2) require their users to maintain secure passwords.

3) treat new accounts with special caution, ensuring that the benefits of abuse are less than the cost of establishing new accounts.

Transmitter vulnerabilites

The Transmitter to Receiver connection is the weakest link in the passage of email from Author to Recipient. This may be inevitable, given the necessity for communications between unrelated parties across the open Internet. All other links in Figure 1 are between parties that have at least an indirect relationship with each other.

The Internet link is uniquely vulnerable to criminal intrusion. It is very easy to set up an exact replica of a legitimate transmitter relay, duplicating everything from message headers, to the envelope Return Address, to the name of the legitimate transmitter, everything but the transmitter's IP address. That has to be the criminal's transmitter address, or there is no TCP connection.

Criminals never use their own names in malicious transmissions. They will either make up a new name, or forge the name of a trusted domain. Criminal use of a trusted domain name provides better access to victim systems, and damages the reputation of the trusted name.

Domain owners who care about their reputation should protect their name by publishing authentication records in DNS (the Domain Name System). Agents who operate transmitters on behalf of another domain (as opposed to transmitting under their own name) should work closely with the domain owner to ensure that the domain's authentication records are kept up to date. Only the owner has access to these records.

Domain owners should:

1) publish the IP addresses of their authorized transmitters (either their own, or their agent's transmitters that will identify using the domain's name).

2) publish authentication records as needed to protect the use of their name in Return Addresses and in From: headers.

3) publish authentication records as needed to provide digital signature protection for the entire content of email messages.

Transmitter agents should:

1) publish the IP addresses of their own authorized transmitters under whatever name will be used to identify those transmitters.

2) work with their MSA agents and other domain owners to ensure all records are kept up to date.

3) implement rate limits on outgoing mail from each user account.

4) work with their MSA agents to provide additional security as needed in their situation. This could include monitoring the content of outgoing messages.

5) provide alerts to anyone who might be an innocent source of abuse.

6) respond promptly to reports of abuse, even if their transmitters are not responsible.

7) maintain a good reputation for all the domain names used by their transmitters.

8) comply with all standards relating to their operations, thus helping others to avoid mistakes affecting security.

9) handle bounce messages (Delivery Status Notifications) in a way that provides maximum reliability while avoiding abuse. This could include adding validation codes to the Return Address on every outgoing message.

Receiver vulnerabilities

Receivers have the biggest burden of all. Over 90% of incoming messages are fraudulent, many from senders that are transmitting such huge volumes that it would be a Denial of Service (DoS) attack on the receiver if it were unavoidable. Luckily, the most persistent sources can be identified by their IP addresses, and blocked without further processing. That still leaves a large number of new addresses that have not yet been added to the IP blacklists.

Filtering the few good messages from this flood of sewage can be a challenge. Traditional filtering methods include statistical analysis of message content, looking for words and phrases that have high probability as spam indicators, and looking for abnormalities in the message headers, using heuristic rule-sets that are updated periodically to follow the latest trends. Both of these techniques reject some legitimate messages, and there is always a compromise between minimizing false rejects and minimizing the amount of spam that gets through to the user's inbox.

Additional "filtering" methods include greylisting and challenge/response. Greylisting involves returning a temporary reject on the theory that only legitimate transmitters will retry after a temporary failure. Challenge/response (C/R methods) involve asking the recipient to respond to a challenge, on the theory that only legitimate senders with important messages will respond. Both these methods are controversial - greylisting as to its long-term effectiveness, and C/R as to its potential for generating unwanted challenges to forged return addresses.

A recent trend in receiver security is to rely less on statistical techniques, and more on the reputation of the Transmitter agent. If that reputation is good, all messages from that Transmitter can be "whitelisted" and passed directly to the recipient's inbox, not suffering the delays and possible losses in a statistical filter. A well-managed reputation system can whitelist nearly all legitimate senders [Taylor08].

Receiver agents should:

1) block persistent sources of abuse efficiently. This is typically done with an IP blacklist.

2) provide clear and concise feedback to the senders of rejected messages, so that innocent mistakes can be corrected quickly. This should be done in the SMTP reject message.

3) authenticate the Transmitter's identity. This is typically done by comparing the transmitter relay's IP address to authentication records under the Transmitter's domain name.

4) perform additional authentications as needed for better security. This can include per-message checks on the envelope Return Address, the header From: address, and the entire message content.

5) assess the reputation of the sender. This can be done using a local or a shared database.

6) filter any messages that cannot be rejected at authentication, or whitelisted at the reputation check, and use the resulting score to prioritize filtered messages for review by the recipient.

Forwarder vulnerabilities

The Forwarder role (played by the Receiver agent in Figure 1) is much like a Transmitter, but instead of sending a message to an unrelated Receiver, the message goes to a related party, the Mail Delivery Agent (MDA) designated by a recipient who has an account with both parties. Ideally, the recipient can ensure that the forwarding arrangement is reliable and secure, turning off authentication checks, spam filters, and any other mechanisms at the MDA that might conflict with the forwarding arrangement, and if necessary, using a private address at the MDA for security. Ideally, recipients should keep forwarding arrangements simple and direct, never a chain of forwarders.

In reality, recipients (non-expert users) make many mistakes. The resulting confusion leads to a special vulnerability that we can associate with the Forwarder. Messed up forwarding arrangements often lead to lost messages, erroneous abuse reports, and more work for both the Forwarder and the MDA.

Forwarding agents should:

1) educate recipients who request forwarding on what they need to whitelist the Forwarder at their MDA.

2) confirm the forwarding arrangement with the MDA.

3) suspend the forwarding arrangement immediately whenever there is a reject from the MDA or an abuse report against the Forwarder.

4) communicate with the recipient to correct the problem.

5) publish the same authentication records for their outgoing IP addresses as they would in playing a Transmitter role.

MDA vulnerabilities

Mail Delivery Agents (MDAs) have the same problems as Mail Submission Agents in authenticating users. Is someone logging in to retrieve messages really who they say they are? Users often have the same agent for delivery as they have for submission. In this case, one authentication mechanism can be applied to both roles. A user who is already logged in to access a mailstore need not log in again to send a message.

Other than these access control issues, MDAs will have very little vulnerability in performing the storage and delivery function. The problems that do arise usually relate to confusion over forwarding arrangements. If the recipient simply forwards messages from some source unknown to the MDA, and the MDA is also acting as a Receiver for that recipient, the two message streams can get confused. Border defenses applied to a stream of forwarded messages can result in authentication failures, lost messages, and improper abuse reports against a Forwarder who is simply following a recipient's instructions.

These problems may be avoided if recipients whitelist their Forwarders, and MDAs turn off their Border defenses for these whitelisted message streams (a specific Forwarder to a specific recipient account). MDAs that do not have this capability should allow recipients to use private alias accounts. As long as an alias is kept private, all mail to that alias may be whitelisted.

Educating recipients to whitelist their Forwarders is difficult for an MDA, because often the MDA is not even aware that a forwarding arrangement has been set up. The Forwarder should notify the MDA when a recipient requests forwarding, and both should make sure the recipient understands what is being done.

Mail Delivery Agents should:

1) provide secure access for recipient accounts.

2) make it easy for recipients to whitelist their forwarders.

3) educate recipients who use forwarding on how to avoid problems.

4) authenticate the Forwarder.