Mentally healthy mind

- Further information, see Mental health

- Further information, see Mental illness

A mentally healthy mind as a subject is one way to explore the general topic of mental health. Generally, the approach by psychiatrists and psychologists is to describe behaviors viewed as unhealthy or dysfunctional but here the approach is the opposite: to try to describe a so-called mentally healthy mind from a Western cultural perspective. This is only one of many possible models and this particular one should not be construed as definitive. It draws from fields including philosophy and psychology but also theater and business and computer science and music and elsewhere. There are two senses of the term: (1) a mind free from diseases and without symptoms of mental illness which describes most persons and (2) an optimally well-adjusted mind which describes few people. This article explores the second sense of the term.

So, what exactly is a healthy mind?

A western model

A Western conception of a mentally healthy mind is a person who functions effectively as a human being, who continues to adapt favorably to the environment, who has self-control and is alert to changes in the environment. He or she responds to change effectively by avoiding pain and finding pleasure, and finds ways to get greater resources, knowledge, power, and tools for survival. He or she has virtue. He or she has an awareness of what is happening around him or her, is self–directed and self–aware, and plans actively since he or she can anticipate a likely sequence of events to imagined possible actions by him or her. He or she isn't stuck in one dysfunctional behavior pattern, or imprisoned by emotions, or subject to mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or neurosis or psychosis. It's a physically healthy person. He or she keeps learning and thinking and growing intellectually, and has the capacity to change his or her behavior to fit new situations, and modify his or her opinions to accommodate new facts. It's marked by adjustment, re-thinking, re-evaluating premises, and leads to greater power, knowledge, and accurate perceptions of people and things and places. It requires both intellectual intelligence as well as emotional intelligence. It enables freedom. It helps a person get along with others in society such that he or she has healthy relationships including sometimes friendships, love, marriage, and other ties of affinity to others. It helps a person survive and thrive. This is one conception prevalent today.

But there are different senses of what constitutes a healthy mind. It depends on one's worldview. Mental health is like beauty since it is in the eye of the beholder. It's culture–dependent. We look at others and make an assessment: does person X have a healthy mind? But the lenses we use to make this perception are colored by the peculiarities of our culture, and refracted by its values and beliefs.

It's difficult for us, as individual humans, to diagnose our own mental health. The question "Am I healthy mentally" requires thinking, but what if our own mind is broken, then how can we think correctly to determine if we're sane or insane? We experience thoughts in our heads and we may think we're fine, but it's possible that we're not totally healthy. Most people probably don't think about this question at all; are they mentally healthy? Is not thinking a sign of mental health? Like it or not, the label mentally healthy is, to varying extents, a label which others in society can and do confer on us, and this label can help or hinder what we do.

Still, there are ways to explore this, but it's perhaps a good idea to review some points first:

- The brain and mind are areas of biology and science that we're only beginning to understand. It is like a black box with millions of neurons organized in ways scientists don't understand, but are learning more each day.

- The label "X isn't mentally healthy" is pejorative with a negative connotation which is similar, in some respects, for a military warrior describing an opponent as a terrorist.

Why mentally healthy is culture–specific

People judge the mental health of others. Generally, people who think like we think, who behave like we behave, who share our values, who behave in predictable patterns, who we think we know, and who conform to standard ways of doing things and whose opinions are in line with the dominant value system are seen as mentally healthy. We generally don't question the mental health of like–minded people, while people who we don't feel we know, who behave in unpredictable ways, who act outside our sense of what is acceptable behavior are more likely to be tagged with a label of mentally unhealthy, whether or not they are indeed mentally unhealthy. There is a feedback mechanism at work here: society rewards particular individuals with money and status and fame and respect and, in a sense, confers the label mentally healthy on persons which advance its agenda and who exemplify its values, and these people, in turn, produce more output along these lines, such as great art, popular talk shows, sold–out concerts or sports arenas. It motivates people to strive in certain ways. Persons we admire such as celebrities tend to be labeled as mentally healthy. In contrast, people at odds with society's values are ignored.

While culture is an important determinant of what is seen as mentally healthy, there are some acts which there is strong agreement across different cultures as being signs of mental illness, particularly suicide, as well as some kinds of extreme non–wartime violence such as mass murder or genocide. If someone kills themself, then it's almost always viewed as mental sickness (still there are exceptions: in wartime when suicide was seen as an act of defiance or as a military strategy such as during World War II when Japanese suicide bombers flew bomb–laden planes into allied warships; some cases of euthanasia in which decrepitude becomes unbearable.) Serial killers are almost always seen as sick.

To illustrate cultural differences relating to the definition of mental health, consider the misogyny of ancient Greece. Male beauty was emphasized so there were rarely statues of beautiful women. According to Classics scholar Elizabeth Vandiver, men resented the fact that women were needed for procreation, and sexual intercourse was seen as a chore in this male–dominated society. Married women were supposed to remain in the home or nearby, and were not allowed to venture about in public or participate in politics or have much presence in the public sphere. In Greek mythology, there were numerous accounts of male figures giving birth, such as the god Zeus giving birth to Athena out of his head, or to Artemis out of his thigh. The prevailing custom in ancient Greece was to tolerate and condone acts in which older middle-aged men were expected to have homosexual relationships with teenaged boys, and this was considered acceptable. In contrast, from the perspective of Western culture today, adult–teenager homosexuality would be considered to be an act of criminality and possibly depravity, and persons who engaged in such behavior would be seen as mentally unhealthy and imprisoned in many societies. However, an ancient Greek such as Aristotle, examining Western societies today in Western Europe or the United States or Japan might see the movement of female rights as wrong morally, and the focus on equality and individual rights as nutty.

Indeed, there is a strong relation between what a culture values, and what persons it defines as being mentally healthy. Most societies prize those persons it most values, who best fit the society's system of values, as models of mental health. We can flip it around as well, and take those people who are famous, and use them to identify a culture's values. Ancient Rome prized skill in war; it's most healthy citizen? Julius Caesar. Ancient Greece prized thinking; it's most healthy citizen? Aristotle. Renaissance Italy prized creativity; it's most healthy citizen? Michelangelo. Anthropologists study the interconnections between people and their cultures. Cultures reward people who exemplify and tout their values, and one way of rewarding these standard bearers is by defining them as mentally healthy. For example, in Western culture today, leading sports stars, celebrities, talk show hosts, some politicians, and not only paid huge amounts of money when successful, but are held up as models for others to emulate as well as being paragons of mental health. To a lesser extent, academics, including professors and scholars are valued, but not as much as a top comedian or football hero. In contrast, persons whose values conflict with those of the popular culture have a much tougher time.

Mental health, in other words, is highly dependent on one's culture.

Another way to illustrate this point is to examine specific people throughout history as well as today through the lens of the value–system of today's culture. Are they mentally healthy in an optimal sense? Consider...

- Julius Caesar. A brilliant military general who outwitted tough opponents on the battlefield, but he made a mistake in underestimating the depth of resentment within the Roman Senate. He was assassinated. Mentally healthy?

- Bill Clinton, a U.S. president from 1992–2000. An exceptional communicator and politician and campaigner who had a sexual liaison with staffer Monica Lewinsky. Mentally healthy?

Napoleon conquered much of Europe but faltered at the Battle of Waterloo.

- Napoleon. Like Caesar, a brilliant commander and dictator but still made serious mistakes at the Battle of Waterloo. Why? Mentally healthy?

- Oedipus. Fictional character from Greek tragedy who unwittingly murdered his father and married his mother. Stubborn, he doggedly pursued the truth of his identity, but when he found out, he poked his eyes out. Mentally healthy?

- Dido, a fictional character in the Aeneid by the Roman poet Virgil. She was compelled to fall in love with the Trojan hero Aeneas, but when jilted, she committed suicide. Mentally healthy?

- Aeneas, the Aeneid character who consistently follows his duty to found the city of Rome, but who, at times, loses his temper. During one battle, he was described as a monster, killing without mercy and without any sense of compassion. Mentally healthy?

- Spinoza, a rationalist philosopher from seventeenth century Europe. His book The Ethics, published posthumously, was widely admired, but he never married, and was overcome by lung problems, possibly from inhaling glass dust, and died in his early forties. Mentally healthy?

- Confucius, thinker from Ancient China. He taught a respect for family values and ancestors in a context of self-restraint,[1] but many of his sayings today are seen as trite nickel-knowledge oversimplifications. Mentally healthy?

- Mike Wallace, the U.S. newscaster and reporter with an impressive career in broadcast journalism, but he suffered from intense bouts of extreme depression which few people knew about. Mentally healthy?

- Georgina Starr, a British artist who smashes sculptures in public, and presents weird video vignettes in presentation art. Mentally healthy?

- Stoics, from Ancient Greece, who believed philosophy was a way of life and a way towards happiness which meant "living in accordance with experience of what happens by nature."[2]

- Odysseus, the supremely crafty Greek strategist who devised the Trojan horse, but who succumbed to pride when he yelled out his name to the Cyclops. He was revered by ancient Greeks but reviled by ancient Romans such as Virgil who contrasted Odysseus' willingness to bend any rule to achieve an effect with the Trojan hero Aeneas who valued duty and faithfulness and compassion. In the Aeneid, Aeneas rescues an emaciated Greek warrior abandoned by Odysseus. Was Odysseus mentally healthy?

- Chrysippus was a Stoic philosopher from Ancient Greece who sometimes showed great arrogance.[3][4] Mentally healthy?

- Leonidas, the Spartan king who held the pass at Thermopylae with 300 fellow warriors,[5] knew his position was untenable, yet he resolved to remain with his phalanx. While defeated by the Persians, their resolve created guilt throughout the Hellenistic world, which eventually led to a Greek victory over Xerxes. Leonidas: mentally healthy?

- Mucius Scaevola was an ancient Roman warrior who defied an opponent named Porsenna by burning his right hand in a fire; the act impressed Porsenna with Scaevola's bravery that he agreed to make a treaty with Rome.[6] Mentally healthy?

The correct answer is in each case, of course, we don't know. It's a matter of judgment, of cultural values, of perspective, and these perspectives are constantly shifting.

Philosophy, religion, culture

Consider different perspectives.

- Philosophy. Philosophers have struggled with issues about what makes a man or woman healthy in a mental sense, and these considerations, to varying extents, revolve around their conceptions of what the good life is and whether it can be obtained, and if so, how. The philosopher Aristotle believed there was such a thing as the good life, and thought that it was one of pursuing virtue and seeking moderation. He thought that life was best if one pursued the golden mean, and that people got into trouble when they lived at the extreme edges of life. Schopenhauer was pessimistic, and suggested that while people were fated to be foolish and that human existence was like a tragic joke, and he felt that the best that people could do would be to enjoy pleasures as much as possible, specifically the enjoyment of art, theater and particularly music. Spinoza believed that most people were subject to a form of bondage or slavery by their own emotions, but agreed that, in general terms, emotions trump reason and rationality at every turn. Nietzsche thought along similar lines, that most people were stuck in fixed patterns and didn't know how to free themselves. Psychiatrist Sigmund Freud thought that mental health required a balance between three essential parts of a person's personality, namely, the id, superego, and ego, and for him, the healthiest persons in a mental sense were those with egos strong enough to moderate the more powerful id impulses, such as basic drives like the need for sex or food or thirst, when they battled with the guilt-laden messages from the superego, like ingrained finger-wagging from an internalized sense of one's judgmental parents. The French existentialist Jean Paul Sartre thought that the world was absurd, but that it still made sense to seek out one's own destiny and strive despite the odds and inevitability of future failure to struggle regardless.

- Religion. Religions, as well, have conceptions of what a mentally healthy person is. For example, Christianity suggests a mentally healthy person is one who loves God, who accepts Jesus Christ as the savior. It's a person who is obedient to the will of God, who prays and obeys religious rules such as the Ten Commandments and the golden rule. Islam counsels faith as well, and sees a mentally healthy person as someone who is devout and believes the Koran. Buddhists think it's a person who's come to some form of acceptance about the nature of life, of the world, and has found a kind of inner peace. Hinduism, Taoism, Judaism, and other religions have differing senses of what being mentally healthy is. In contrast, atheists see healthy-minded people as persons who don't accept religion or its precepts, and who think that people are healthy only if they don't follow religion, while the believers in religion think that religious belief is the right way to approach life, generally.

- Culture. Different cultures, as well, have had different senses of the best approaches to living. The ancient Greeks believed it was knowledge of what it meant to be human, partly by contrasting human existence with that of the gods and goddesses; it meant knowing one's place in the world, realizing that as humans we have a limited and finite existence with a usually undeterminable deadline, which required humility and religious devotion including faithful performance of religious rites. It meant accepting one's fate, not trying to change one's fate, and avoiding excessive pride or what they called hubris. The ancient Romans, as well, believed during most of their Republican days, and well into the Empire, that it was necessary to follow exactly, and in the correct order, the steps necessary to perform a religious rite; one mistake necessitated that the entire ritual would have to be repeated from the start. Freud's disciple, Carl Jung, suggested that the mind forms symbolic archetypes of cultural ideals.

While there are many constantly changing perspectives on what a human mind should be like, and how it should function, it's possible to put forth a model, combining a variety of perspectives, to describe a person with a healthy outlook, mentally, from a psychological perspective with input from philosophy. Indeed, in the mental health field, it's often easier to describe mental illness, and to point out persons or diseases or disorders which are clearly unhealthy or dysfunctional, but it's much more difficult to describe a person that is seen as mentally healthy. But this exercise can be helpful in thinking, and while it's impossible to specify one exact model that all people will accept, rather, it's helpful as a way to encourage introspection to try to attempt such a model, so let's begin with politics.

A healthy mind is like a deliberative democracy

This town hall building in Halifax in the United Kingdom is where citizens and officials meet to discuss public matters.

One can think of a person's mind like a kind of functioning and deliberative democracy. Imagine a small town meeting hall like in New England from the seventeenth century in America. Men [7] came together, once a year, to discuss common public matters like whether a schoolhouse should be built. At the meeting, there was an agenda of issues needing discussion, usually agreed upon in advance by officers who were elected at the previous meeting the year before whose job was to select matters of importance, and to disregard unimportant issues, so the meeting would become productive. For example, suppose the issue of building the schoolhouse was important, but road repairs weren't; they'd choose that issue to talk about, or plan to have most of the meeting focus on the schoolhouse issue. During the discussion, different people volunteered their thinking, offering information and viewpoints, but they didn't all speak at once; rather, they took turns, hopefully following the discussion and keeping to the topic at hand, so that others, using reason, could follow their thinking. And it helps immensely if people who don't know anything stay silent, hopefully listening to the people who do know things. After different views were given, and when the group believed that enough of the possible topics had been brought up, then they decided to close discussion on that topic, and vote. Sometimes this meant a decision regarding a future course of action. Hopefully, this vote would entail a choice made intelligently after weighing different possibilities, and considering the ramifications and cost-benefit analysis of various options. Then, the group would move on to another topic, deliberate, decide to close discussion, vote, and move on; when all the topics had been dealt with, and decisions reached, then ultimately the meeting would be adjourned.

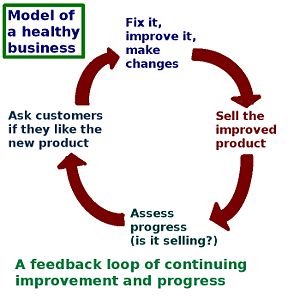

Feedback is important. Ideally, the process never ends, in the sense that after a decision is made, the mind actively seeks feedback about this choice: was building a schoolhouse the right decision? Were there enough children to have made the decision sensible? Was there a better alternative available such as waiting for ten years for funding from a philanthropist or was building a tent a better option, and having classes only during the warmer months? And how important was it to educate these children anyway? What if there are no competent schoolteachers available, what then? This kind of feedback, ideally, in a mentally healthy person, keeps streaming in, being recorded and noted, and next year, at the next meeting, a hopefully wiser, more knowledgeable group of citizens meets, discusses matters again, and either amends or furthers or abandons a course of action. Habits are vital, and this takes time. So people, through experience, and by learning through trial and error, develop habits about conducting meetings, or in the example of thinking, the habits of decision making, thinking, learning. The feedback principle characterizes a healthy business as well as a healthy mind: a firm which routinely monitors its customers, ask their opinions, and tries to understand their needs operates according to a marketing orientation; accordingly, when customers needs change, it alters its products and services to meet those changing needs.

One can think of a healthy mind in the same sense as a deliberative functioning democracy in that it actively gathers real–world information about the environment, by focusing on events, making perceptions, remembering. It thinks. It weighs options. It prioritizes tasks. It allots time slots for deliberation. It deliberates within itself. It uses logic, sometimes. It imagines likely consequences to possible choices. It allows a certain amount of time for this kind of reflection, and when it's reflecting, it focuses on these decisions. And then, at a certain point, and based on the best available information it can get which understandably isn't perfect, but the best it can get––then it decides on a course of action. It acts. This course may turn out, later, to have been wise or foolish, but the important thing is that a decision was made, a choice, a path chosen out of a few possible alternatives. A healthy mind is like a deliberative democracy that meets inside itself, thinks, weighs choices, and makes decisions, hopefully that are right and helpful and that lead to increased opportunities in the future.

It's important to realize how difficult it is to keep this process going. Problems loom at every stage which can block deliberation. In a New England town hall, for example, it's possible that a few disruptive and intolerant persons disrupt the meeting by shouting or yelling because they're intensely concerned about one particular issue. They're fanatical about some irrelevant topic, such as witchcraft; but it really isn't important to the group, and their thoughts aren't based on any kind of reality (assuming there aren't any witches). Well, this is a problem for a democracy. In an individual mind, the same kind of problem can occur: perhaps one particular thought or concern tries to dominate the discussion within one's mind; a loud-mouthed individual (or too-powerful idea) can shut down thinking.

Here's another problem: suppose some people at a democratic meeting are genuinely afraid that others are witches? They'd wouldn't listen to their viewpoints or heed their counsel, and instead of following the discussion about some matter of public affairs, they'd stop listening since they were worried about possible malevolence of the possessed. This irrational fear would be an obstacle blocking the sharing of information within the community. It's possible the community could still explore some topics, but in such a situation, then other topics (or people) are effectively "off-limits", so the discussion is hamstrung, in a sense. Similarly, inside a person's mind, if he or she is afraid to think certain thoughts, perhaps because the thoughts are seen as dangerous or bad or evil, then this fear might hamper the enterprise of thinking, and prevent a person from arriving at a reasonable conclusion or decision. Freud used the term repression and sublimation to describe a person resisted thinking about certain thoughts, that is, they were unable to deal with certain topics. This hinders a person. It isn't mentally healthy.

An individual or faction at a town meeting may be totally focused on only ONE relatively unimportant issue, and can't get interested in a schoolhouse or even road repairs; rather, they're scared about flooding, despite the fact that the community is not along any river and there are no dams above the town. When the subject of the schoolhouse is underway, they keep trying to bring up flooding, essentially interrupting and derailing the discussion. This is unproductive. By analogy, an obsessive or compulsive person is someone who thinks constantly and worries about one less–than–important topic such as germs, for example; this thought dominates their brain to such an extent that they are unable to devote mental resources to other pressing issues. This, too, isn't healthy mentally.

Suppose there's an issue which people are reluctant, for whatever reason, to confront. They won't talk about issue X. For example, members of the United States Congress are reluctant to even mention the troubling issue of Social Security underfunding, since a whiff of tampering could get a representative running for re-election to lose his or her seat. It's called the third rail of politics: touching it will get the speaker electrocuted, but failing to deal with budget shortfalls could cause massive problems in the future. In a mind, the same thing can happen. A troubling but important idea may be avoided, but trying to repression (psychology)repress it can block thinking about related issues.

Or, suppose that in a democracy, there is a group of people attending the meeting who are ignorant of events yet think they're knowledgeable. They inject ill-informed viewpoints into the discussion, polluting it. As a result, they can dumb down a meeting, perhaps by introducing extraneous or spurious facts that distract attention away from relevant facts. Or, suppose that people in the group are smart, thinking, but they just don't know some particular fact relevant to the discussion. They're ignorant, but may not know that they're ignorant; in the same sense, a person, actively trying to think about things within their own mind, may be similarly ignorant. They don't know the necessary information. They think they do. But they don't. By analogy, a person thinking about some topic may think they know something but don't, possibly leading to a flawed choice. This stuff can happen.

Chart comparing problems with a town hall meeting with psychiatric disorders.

What every town hall meeting needs is some kind of supervisory or management function which limits discussion timewise, perhaps a scheduling officer allocating time limits to particular subjects. Otherwise it's possible that the meeting runs late. It debates on and on and on and on and on. It wants to examine every possible fact and every possible choice in such detail and won't make any decisions until it's sure that it's perfect. This, too, is a kind of mistake, because there is no such thing as perfect information but only intelligent guesses. It must make decisions and get on with life. By analogy, there are some very intelligent people who, because of their extraordinary brainpower, want to make every decision perfect, but in this deluded effort, they take so long trying in vain to make every determination right that they don't have enough time to actually achieve the goal. They think and think and think. But there's no time left to act. It's too late. For any intellectual process to work effectively, there must be some kind of balance between time spent thinking and time spent acting. It's a matter of proportion. Too much thinking isn't good; not enough thinking isn't good either; there must be balance. There must be some oversight function in the brain which apportions time between these two tasks, and makes sure that there is sufficient time, and in the right amounts, for both tasks. It's difficult to get this balance right.

Suppose that in a democracy, the people who show up to deliberate are all blind. They can't see. They're good people, smart and responsive, but they lack a perceptual capability because of their affliction. It's not their fault. But what's problematic is if they're asked to make some decision that depends on their having seen things that they can't see. If they know that they shouldn't decide on certain areas, because of their lack of visual ability, then they can intelligently recuse themselves from such a decision, or possibly asked sighted persons for assistance in helping them decide something.

What's key in both a deliberative democracy, and a healthy functioning mind, is the continuing and ongoing process of thinking, exploration, perceiving the real world as it is, and making best-guess choices, and then following up on our choices to do a kind of self-assessment to get feedback. Humans have limited abilities. Our brains are large but finite with limited processing power. We have eyes that are better than most species of lizards, but weaker than those of eagles. Our sense of smell is lackluster compared with most dogs and polar bears. We have the potential to think rationally, logically, but it's difficult since much of our thinking relies on hunches and guesswork. We can be weakened by disease, hampered by youth and inexperience as well as the vagaries of old age. We're mortals. We're born, live, and die. We don't live forever. We're not immortal or like the so-called deathless ones like the Greek gods and goddesses from Greek mythology.

The mind as an organ of thought

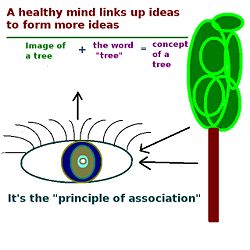

The mind links ideas according to the principle of association. It allows us to combine simple thoughts and sounds into more complex ones in an ever increasing web of abstract thought.

The brain's job is to think. That's it's task. A healthy mind, then, thinks well.

Thinking

Consider that our brains have to process potentially huge amounts of information. What's important? What isn't? Some mental activity involves ferreting out the distractions. The exact mechanisms of how this happens in the brain is not well understood so far, but it's important that this happens. For example, a person could be reading a book outside of a cafe in Britain such as the Panton Arms, and be thoroughly immersed in the storyline, but if somebody else calls their name, they'll perk up and pay attention; if another name is called, it most likely will not even register in their consciousness. How does this happen? How do people learn to respond to their own names and not other names? While scientists continue to explore these areas, an important part of mental health is having concurrent processes going on in the brain at the same time which allows one activity (reading) to take place with full concentration while permitting another activity (hearing one's name) to interrupt the first activity. In contrast, if a person was reading, and a friend came by and said their name, but they didn't respond but kept reading, the friend would likely conclude that something was wrong, perhaps with the person's mental health.

But the ability to concentrate marks a healthy mind. It's paying strict attention to a particular subject, following it, grasping the logic, staying on task, absorbing new information and assembling it into a coherent whole while, at the same time, permitting interruptions when important stimuli present themselves. A person who only responds to external stimuli and can't concentrate may be thought of as scatterbrained or harebrained or possibly have a mental illness such as Attention deficit disorder or A.D.D. and, as a result, will have a difficult time learning new things. At the other end, a person who can only concentrate, but misses important signals, may be described as being lost in thought, and this can be dangerous as well, particularly if the new signals suggest something requiring instant action, such as a boulder rolling down a hill and crush them. A person lost in thought could get squished. In another case, some people may be particularly good at focusing on some types of areas, such as counting, such as an idiot savant, and may have impressive skill at adding or multiplying numbers with many digits in the blink of an eye, but may lack an ability to understand the value of something like money, like the character Rainman in the movie of the same name. Rainman could count hundreds of spilled toothpicks in a few seconds, but couldn't understand the value of a dollar. This suggests, again, the wisdom of Aristotle, who thought it was best for humans to live as a means between the extremes, that is, to be able to concentrate when necessary, but to be distracted when necessary, and to shift between the two modes of thinking as required for survival, and not to live at either extreme. It suggests a kind of mental management function of the mind is vital in addition to sheer processing power, and is similar to a deliberative democracy by a meeting which can focus on particular topics in the agenda, and stay focused as necessary.

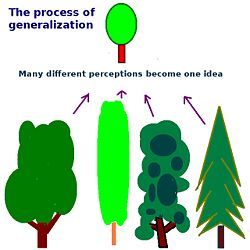

Another characteristic of mental health is the ability to craft generalizations. This means distilling complex ideas into a simple rule or fact or law, simplifying, losing much of the unnecessary complexity while boiling information down to a fraction of the size, but which still allows us to grasp things and work with knowledge. One generalization is what goes up must come down and this is a helpful simplification which applies to almost all situations (except: certain space rockets) so a person purchasing a trampoline, and jumping on it, won't worry about possibly catapulting himself or herself into deep space. Another example, a boy or girl may throw enough stones and rocks, bite a couple, try to smash it with a hammer, and then pretty much come to the generalization that all rocks are solid and hard to smash. This is a huge time-saver and benefit when it comes to dealing with a complex environment with a wide variety of shapes and things and objects; if the person becomes a teenager and sees a boulder, he or she will know, without having to try to smash it with a hammer or jump on it, that it's likely to be solid, and can use this information intelligently, perhaps to stand on the boulder to get a better view of the countryside. He or she will know that the boulder will support their weight, since they've learned from the earlier generalization to trust the solidity of rocks. Of course, generalizations are not perfect, and can lead to mistakes, since there may be some rock-like shapes in the world which aren't solid, and can lead to unpleasant surprises. But for the most part, generalizations (when they're mostly correct) are extremely helpful. They're the mental building blocks for more complex abstractions since they enable the mind to grasp a whole class of objects or problems without having to explore, individually, each one.

Generalizations, of course, are based on the idea of the principle of association which allows us to link one idea with another, assembling them into more sophisticated associations and higher level thinking. At the most basic level, we link in our heads one idea with another, letters with sounds, a word with an object, many objects with a group, basic ideas with a concept, and so on, until in our heads we have a system of interrelated ideas, somewhat akin to an online encyclopedia such as Citizendium, in which ideas (articles) are connected via wikilinks of association in a vast network which hopefully has some basis in reality. It enables a worldview. We construct our best guess about how the world works. Is it right? It's a guess, incomplete, based on partial and sometimes incorrect information, and ultimately we don't know. Hopefully our worldview is comprehensive and accurate and easy to use.

Reality is like a full picture showing everything, including this tree called a Bonsai Trident Maple.

But getting this connection to reality is a difficult perceptual and conceptual task. We have to make do with incomplete information, sometimes whispered sounds, muffled voices, blurry pictures, unfinished sentences. We try to solve conceptual jigsaw puzzles with pieces missing, including the end and corner pieces. It's difficult to envision the complete picture. In diagnosing mental illness, there are a variety of terms which describe inaccurate interpretations of reality such as arbitrary inference, catastrophizing (making a mountain out of a molehill), dichotomous thinking (being unable to see a middle ground or compromise, so that a person is either a friend or foe), overgeneralization (example: a woman who says my boyfriend dumped me and therefore concludes incorrectly that no one loves me), personalization, and selective abstraction (example: a man walking by hears other people laughing, and thinks mistakenly that they're laughing at him). It's easy to make mistakes when we're tasked with photographing and processing huge amounts of information with a tiny handheld camera with limited memory capacity.

Emotional intelligence

It's skills like these which are essential to interpersonal relations, sometimes called social intelligence[8] meaning the "ability to understand men and women, boys and girls––to act wisely in human relations," according to Thorndike in the 1930s.[9] In 1990, with their term emotional intelligence, researchers Salovey and Mayer viewed emotions as organized responses crossing over the boundaries of psychological subsystems, and it involves the "ability to monitor one's own and others' feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one's thinking and actions." It requires the ability to comprehend another's feelings and to re-experience them oneself or empathy. They wrote:

The person with emotional intelligence can be thought of as having attained at least a limited form of positive mental health.<bold>Salovey and Mayer 1990</bold>[9]

Skill in handling emotions helps a person read others by correctly interpreting information such as facial cues and gestures, and can lead to success in love, friendships, marriage, and other areas of interpersonal relations. The New York Times science writer Daniel Goleman wrote that "in marriage, emotional intelligence means listening well and being able to calm down. In the workplace, it manifests when bosses give subordinates constructive feedback regarding their performance." It's a vital skill leading to efforts to teach children such tasks as conflict resolution, impulse control, and social skills.[10]

Goal-oriented behavior

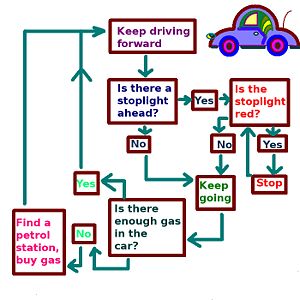

A healthy mind can lead itself and the body in a series or sequence of goal directed behaviors. Think of driving a car from point X to point Y. The goal is point Y. To reach this goal, the mind must engage in planning the route, making specific choices along the way, paying attention to road signs as well as other drivers, allowing for unexpected developments such as bridge repairs, and accounting for weather conditions such as rainstorms or icy surfaces. It's an interactive task demanding that one pay attention to developments, and which requires a fairly intense amount of mental concentration to do successfully. If a person can drive a three thousand pound automobile past changing circumstances without causing a crash, and get to the destination in a reasonable amount of time, then the driver is thought to be mentally healthy in this context. He or she made the trip successfully.

Reaching a goal is like being able to construct one's own computer flow charts on the fly. It's writing new ones when new obstacles or opportunities present themselves, while keeping the ultimate goal in sight. It's a kind of dual consciousness: paying attention to the immediate problem, while keeping the long term goal in the back of one's mind. If an obstacle blocks the path, then we drive around it. If a shortcut emerges, we take it. It's constant re-adjustment en route. There is an assumption of a degree of mental health, and clear indications of competence in some basic areas of cranial activity.

Analyzing behavior

But suppose a person drive to point Y every day for no conceivable purpose. Nobody knows why he or she makes this journey. He or she doesn't know why as well. The trip happens flawlessly, but why? And suppose, further, that there is no reason for this trip. It's totally pointless. Then, it's possible for us, examining this driver, to still conclude that the person isn't totally mentally healthy, that is, that mental health isn't merely achieving goals, but rather involves deeper issues regarding freedom, philosophy, and meaning in life. Behavior only makes sense by looking at it in the context of someone's overall choices during their lifespan, as well as the context of the civilization they live in.

Accordingly, a repetitive habit may be seen as good depending on assessing its purpose in a person's life. The philosopher Immanuel Kant, who wrote intelligent treatises on numerous subjects, had a habit of a daily walk which was so regular that people could "set their clocks by him" as he passed by.[11] As seen in the context of his entire life, Kant was seen, then and now, as having an extraordinarily healthy mind, and in the context of his overall life, the daily walk doesn't appear nutty, although perhaps a bit eccentric? A psychiatrist, examining the patterns of a patient, tries to see how specific behaviors relate to the whole person and whether they mesh with his or her goals.

Suppose a person drives seemingly aimlessly to different destinations. Why? On Monday, they drive to the top of a mountain, on Tuesday to a river bend, on Wednesday to a forest, on Thursday to a windy beach, on Friday to a waterfall. The behavior may appear erratic, but maybe not: suppose they're a nature photographer taking pictures of selected locations for a future magazine article; the context suggests it makes sense and the person is mentally healthy.

Cause-and-effect

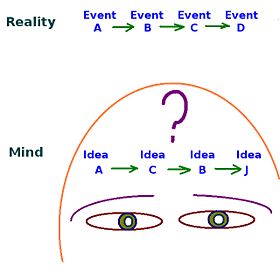

The philosopher Spinoza believed that a healthy mind would form linkages between a series of ideas and an external series of events. He proposed a correspondence theory suggesting there was a one–to–one correspondence between ideas and events. Accordingly, he advocated that humans should try to form longer and longer chains of ideas which are correctly understood (he used the term adequate) which accurately predicted reality. For example, suppose one wants to get a haircut. Suppose that's Event D (see diagram). That's the goal. To get there, one needs to get in the car (A), drive to the barbershop (B), park the car (C), and walk into the shop and request a haircut. Those are the steps. If a person has an adequate sense of these correct steps in the correct order, then he or she can be described as more mentally healthy than a person with confused thinking, perhaps who requests a haircut without driving to the store first, for example.

A hierarchy of purposes

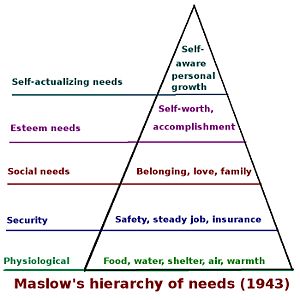

What defines a mentally healthy mind is when a person has a hierarchy of purposes, ordered in such a way that the higher–order purposes (such as nature photography) can be realized when the lower–order purposes (eating, drinking, sleeping, shelter) are taken care of. By accomplishing successfully the lesser needs, it's possible to achieve ambitious goals such as becoming a top nature photographer, and the extent to which lesser goals fit into a sensible hierarchy of a larger goal suggests the extent to which a specific person is self-directed. While the hierarchy is not fixed, and may change as circumstances change, a healthier person will tend to keep the top–level goal fairly firm, while allowing for shifts in lower–priority tasks such as haircuts (which will change as circumstances change.)

A particular person may go through stages, perhaps floundering in their teens, wasting time in their twenties, and perhaps latching on to a career trajectory in their thirties. Some lives are marred by bouts of mental illness or mistakes in judgment, but a person can sometimes learn from these experiences and find a way towards greater happiness and fulfillment.

A theory along these lines, termed self actualization, was proposed by the psychologist Abraham Maslow in 1943 in a paper entitled A Theory of Human Motivation. Maslow suggested that people had a hierarchy of needs, and that it was necessary for the basic needs to be fulfilled first before advancing on to more sophisticated needs. Basic needs such as water, food, air, sleep had to be met before more higher–order needs were met such as security needs, social needs (love, affection), and esteem needs (see diagram). The highest needs he termed self–actualizing needs and described people who are self–aware, concerned with personal growth, less concerned with the opinions of others or the crowd, and keenly interested in fulfilling their potential. What characterized fulfilled people? Maslow studied people that impressed him, including Albert Einstein and Eleanor Roosevelt. He characterized self-actualized people as having:

- Acceptance and Realism, with realistic perceptions of themselves, others and the world.

- Problem-centering focus on solving external problems and helping others and finding solutions. They're motivated by personal responsibility and ethics.

- Spontaneity in their thoughts and behavior, and while they can conform to social expectations, they can be open and unconventional.

- Autonomy and Solitude and can operate in independence and privacy as well as social situations.

- Continued Freshness of Appreciation so they can find joy even in simple pleasures.

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), trying to help patients as well as himself, developed a provocative and influential theory of psychoanalysis. Freud suggested that persons go through so-called psychosexual stages of development which he named oral (sucking and eating as a baby), anal (pleasure from bodily control over waste), phallic (sexual desire related to the opposite–sex parent), latency (an intermediate stage characterized by less interest in sex), and genital (for adolescents onwards where sexual urges are expressed in sexual relationships). Freud suggested that persons who get stuck at one stage (he used the term fixation) have trouble progressing to later stages and developing fully as persons, which prevented them from attaining an intelligent balance between his hypothetical three basic structures of the personality. These parts were: the id (basic powerful subconscious drives such as hunger and sex), the superego (a conscience and internalized parental guide emphasizing rules and order), and the ego, an adult reality–based mechanism to resolve conflicts between the id and superego. According to Freud, when conflicts are not handled properly, the mind can engage in a variety of so-called defense mechanisms (his terms: Denial, Displacement, Intellectualization, Projection, Repression, Rationalization, Reaction Formation, and Sublimation) to cope, but his therapy was based on teaching a person to understand these mechanisms and resolve conflicts as a mature and reasonable adult.[13][14] Frieda Fromm-Reichmann (1889–1957) was a psychiatrist and contemporary of Sigmund Freud who pioneered an intensive method of psychoanalysis which emphasized empathy, honesty, and directness, and she came to believe that experiences in early life were more important than psychosexual motivations in mental health.[15] Alfred Adler, a student of Frued as well as a collaborator, also broke with Freud, and he believed personality was formed more by interpersonal interactions rather than conflict within a person's mind between hypothetical personality structures such as the id, ego, and superego. Adler believed all behavior has social meaning and that the human personality has unity and guiding themes, and that an infant's inferiority complex, which is developed because of its helplessness, leads naturally to a drive for greater self-control.[16][17][18] Fritz Perls along with his wife Laura Perls, based on work by Max Wertheimer, invented gestalt psychology which examines the human mind and behavior as if they were interlinked into one whole, and in which part–processes are only explainable in terms of their relation to the "intrinsic nature of the whole."[19] Gestalt theory has important ramifications for perception, and suggests that the "whole of anything is greater than its parts" in the sense that looking at parts in isolation is not sufficient to understand the whole.[20]

Advice from philosophers and religious thinkers

Asking the big questions

To live with an optimal state of mental health, in the view of many philosophers, is more than intelligence or correct information processing but ultimately coming to grips with metaphysical questions: why are we here? what is virtue? what is happiness? what is good? is there a God or are there gods and goddesses like the Ancient Greeks believed? While philosophers may not agree on the answers to the questions, they might agree that wrestling with these issues brings benefits in the sense of helping people get a better understanding of how to live our lives. The Greeks compared themselves with immortal or so-called deathless ones, trying to find meaning in life when it's not readily apparent. In the Iliad by Homer, the hero Achilles wrestles with the question of what life is all about. Is it about honor and glory? Or enjoying a long life? Achilles had a distinct choice between these two options: glorious honour throughout all time but with a short quick life, or a long uneventful obscure life. He chose everlasting fame and paid for his choice with a quick death, but he came to regret his choice, according to Homer. Was Achilles mentally healthy? He achieved wonderful glory, but he died. What's the object of life? And that's a question we must wrestle with.

Was Einstein mentally healthy? The famous physicist was asked at one point to consider becoming prime minister of the state of Israel, but he declined, saying "I have neither the natural ability nor the experience to deal with human beings."[21] Socrates might have applauded such a decision; he suggested the prime virtue was to know thyself, and if Einstein knew that he wouldn't succeed in politics, then he made the right choice. Spinoza suggested it was up to individuals to determine what was meaningful in life, and that virtue was its own reward, and that it was good for people to pursue what was good for them. What was good? For Spinoza, good meant what's useful to us (a thing or person or activity or place) which helps us affect or be affected in ways that are helpful to us. Nietzsche, who read Spinoza and who was a forerunner of later existentialists, would equate mental health with a will to power, and that mastery over one's environment was a clear sign of mental health.

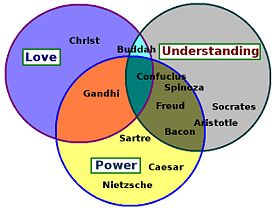

One can examine mental health from any of the three major philosophical approaches––love, understanding, and power––and still be left with more questions and a seemingly never-ending search for meaning. If one sees the mentally healthy person as a person who can love (a perspective by many religious leaders including Christ), what then? Is a mentally healthy person someone who understands (from the perspective of rationalist philosophers including Descartes), then what? Or a person with power (such as Nietzsche). Or some mixture of the three? Regardless, questions remain. It's up to us, as humans, to try to determine what life is all about, and there will never be a definitive answer to these questions that satisfies everybody.

Existentialist philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre in his book On Being and Nothingness (and depicted in his story Les Jeux Sont Faites) believed that humans are "condemned to be free" and that we create our own purpose by assuming responsibility for our life. It's not good to succumb to existentialist abstractions such as despair, angst, absurdity, alienation, isolation, meaningless, or boredom, according to this view. Mental health is marked by refusing to be overcome by these obstacles, and facing death straight in the face and going about one's life regardless. Freedom requires that we're accountable for our actions, according to Sartre. But the philosopher seen as one of the original existentialists, Søren Kierkegaard, believed intensely in Christianity while other existentialists such as Nietzsche and Sartre did not, they agreed about the need to make free choices.

Religious perspectives about mental health can be entirely different from philosophical ones. The Christian values of ascetism, self–denial, and humility are at odds with many contemporary values. In the later stages of the Roman Empire, groups of believers known as monks broke off to live in relatively isolated communities, and lived an austere, spartan existence away from worldly pleasures which they saw as "temptations"; was this mentally healthy? They thought so at the time.

The Buddhist perspective emphasizes open–mindedness, exploration, creativity. A Buddhist teacher explained in 2010:

We start by bringing an open, inquisitive, and skeptical mind to whatever we hear, read, or see that presents itself as the truth. We examine it with reason and we put it to the test in meditation and in our lives. As we gain insight into the workings of the mind, we learn how to recognize and deal with our day-to-day experiences of thoughts and emotions. We uncover inaccurate and unhelpful habits of thinking and begin to correct them. Eventually we're able to overcome the confusion that makes it so hard to see the mind's naturally brilliant awareness. In this sense, the Buddha's teachings are a method of investigation, or a science of mind.[22]

Taoism offers a somewhat different approach:

Tao, often translated in the West as the way, concerns the mysteries of life, not its manifestations. Taoists speak of embracing the uncarved block, not the sculpture. The goal of Taoism is to live in harmony with Tao, which means not acting for self but also not leaving work undone ... Tolerance is actively embracing the other person's difference.[23]

Actor Dana Delany has imagined herself as a nurse, as a womens' rights activist and dozens of other roles. Some psychologists speculate that the discipline of role-playing helps a person have better mental health and develop empathy and compassion.

Even discipline from such activities as acting can have positive consequences, according to some theorists. By role-playing, we get to walk temporarily in somebody else's shoes, to try to see the world from an entirely different perspective, and develop empathy. It's no accident that many of the best actors and actresses around the world often have great empathy and compassion, since their job requires them to gain new perspectives and to try to see things through the eyes of an imagined person. Some therapists encourage their patients to engage in role-playing and theater-type exercises to encourage this empathy and understanding.[24]

If there is some agreement from philosophy about mental health, perhaps it may be in the area about not becoming a prisoner to the emotions. This was central to thinkers such as Spinoza who saw humans as prisoners of the emotions, like a form of slavery or bondage, which trumped the power of reason in most circumstances and kept people from rising to their highest potential. Spinoza figured that if one wanted to triumph over the emotions, then it was necessary to try to understand them, and to realize and accept that all events as well as ideas are determined, and with this acceptance, to try to get a handle over fate by seeing how things couldn't happen otherwise. A mentally healthy act for a philosopher such as Spinoza is: shrugging one's shoulders. It happened. Stuff happens. We shouldn't get too frazzled about it. If we look at the world from the perspective of an infinite Being such as God or Nature (Spinoza equated the two, although this is somewhat of an oversimplification), then from the perspective of God or Nature, everything is determined, fated, caused by necessity to happen in a predetermined way, and there's nothing we as humans can do about it, according to this view. Ancient Greeks looked at destiny as if it was the will of Zeus that things would happen in a certain way. Therefore, forgiveness of oneself and others isn't merely a smart moral practice, rather, it's logically the smart thing to do. But as humans, Spinoza argued, it's possible for us to get a greater share of the determining by trying to understand the cause-and-effect relations between things and between ideas, by extending longer and longer chains of causation to help us get a better handle over our environment, to live better, to have more money and status and wealth and success with healthy relationships, to be healthier physically, to figure out what we want to do in life, and ultimately, to have greater mental health. It's smart to accept that the environment and world we live in has a big say in determining our overall happiness quotient, and there's a benefit from accepting the many givens we're given: our time and place and country of birth, our parents, our DNA, our past, our body, our brain. If we can't choose which society we're born into, and we can't pick our parents, then at least we can realize this, and do the best with what we've got. This helps us calm our emotions. Why get worked up about something if it's not our fault?

But there have been arguments put forward which don't see emotions as the problem, but rather as valuable intelligence which should be embraced and encouraged. Martha Nussbaum in her book Upheavals of Thought (2001) advocated a neo–Stoic approach which sees emotions like love and grief, far from irrational distractions, are "intelligent responses to the perception of value." Nussbaum argued that our common vulnerability and inevitable victimization by fate leads logically to an ethics of empathy and love, and that the "pain and partiality of emotion are a value–laden mode of thinking that must be accepted if we are to create a just and compassionate world." Like the existentialists, Nussbaum rejects victimhood which she sees as incompatible with human agency. Instead of the human ideal being a love of wisdom, it should be about a "wisdom of love".[25]

An optimally mentally healthy person builds on known information by learning through education and reading and asking questions. It is easier and faster to gain knowledge and wisdom by education rather than trying to re–discover information by oneself.

There is widespread agreement that excessive emotion is counterproductive such as anger or fear. The latter emotion is the essential prime ingredient to a whole slew of mental illnesses labeled as paranoia, including anxiety disorder as well as panic attack. Spinoza believed emotions were predominant and humans were led by them, and concluded that "insofar as men are subject to passions, they cannot be said to agree in nature", and that, torn by passions, people can be "contrary to one another" and all sorts of ills happen.[26] But it's part of being human.

Buddhist philosophy suggested that all pain came from attachment to things which change. We develop attachments to activities, behaviors, things, even people, but these change. We fall in love, but the person we fall in love with changes. And suffering can result. Break these attachments. Let go. This is a Buddhist take on achieving mental health. The philosophy doesn't like the multi-tasking ethos of modern civilization, but prefers that we focus on one thing at a time; one Buddhist counseled, when you sweep the floor, sweep the floor; when you rest, rest; but don't sweep the floor while wishing you were resting. Christianity and Islam and Judaism all see, to varying extents, the principle of obedience to a higher power as a key to being healthy mentally. Even the ancient Greeks suggested it's wise to have humility and realize we're mortal, the deathful ones, and to avoid excessive pride which they termed hubris at all costs. We're human. We're born, live, and die. So act the part.

Pathyways to maintaining mental health

It makes sense not to judge others too harshly. One mantra from a Gestalt reading went as follows:

- "I do my thing, and you do your thing.

- I am not in this world to live up to your expectations."

- And you are not in this world to live up to mine.

- You are you, and I am I.

- If by chance we find each other, it's beautiful.

- If not, it can't be helped."[27]

Dr. Adam Cash suggested the key to mental health were ten steps:

- Love yourself and accept yourself as you are

- Struggle to overcome, yet learn to let go

- Stay connected with other people and nurture relationships

- Strive for freedom and self-determination

- Find your purpose and work towards your goals

- Find hope and maintain faith and have a "positivity bias"

- Lend a helping hand with charitable activities

- Find flow by being deeply engrossed and focused on selected activities.

- Enjoy beautiful things in life, including music and art.

- Stay flexible. Be ready to change. It takes courage to change our ways.[27]

Physical health

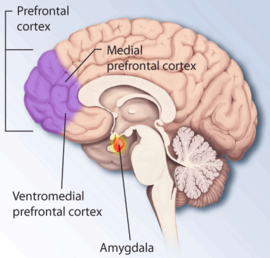

For a mind to be powerful and effective, it depends on a healthy body. The nerve cells inside the brain must be well nourished, free from disease, healthy, undamaged, without tumors or cancer or dangerous buildups of toxins, and adequately spaced so they don't interfere with each other. A person suffering from dementia or Alzheimer's disease can't process information adequately, and cannot be described as having mental health. The section of the brain known as the amygdala, when underdeveloped, can lead to poor impulse control. It is not understood how the technique of giving the brain a small electric shock to some depressed patients has the effect of causing them to feel better.

Inside the brain there is a system for rewarding itself based on chemicals such as dopamine. It's released like liquid praise for actions it wants repeated, although scientists continue to explore exactly how this system works. A healthy mind, ideally, dribbles out rewards intermittently to foster behavior which it likes, and withholds it on other occasions, by releasing these chemicals as needed. The problem with drug abuse, of course, is that it rewires the brain so that chemicals are released not as a reward for accomplishing a self-directed task, or for seeing something beautiful, or from some hopefully healthy activity such as sex with a partner, or exercising, but rather the chemicals are released because of the drug itself. This is why narcotic drugs such as heroin or methamphetamine are so dangerous, since they can not only interfere with the brain's internal rewards system, but can usurp the brain's activity of rewarding behaviors and actions which are good for the person. Addicted to narcotics, a person loses self-control, but becomes a slave, in effect, to the drug. Which purpose predominates? The person's? Or the drug's? The former is good, the latter harmful, obviously.

Other areas

References

- ↑ Jeffrey Riegel. Confucius, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Sep 5, 2006. Retrieved on 2010-04-27. “Learning self-restraint involves studying and mastering li, the ritual forms and rules of propriety through which one expresses respect for superiors and enacts his role in society in such a way that he himself is worthy of respect and admiration.”

- ↑ Dirk Baltzly. Stoicism, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Thu Feb 7, 2008. Retrieved on 2010-04-27. “Chrysippus amplified this to (among other formulations) "living in accordance with experience of what happens by nature;" later Stoics inadvisably, in response to Academic attacks, substituted such formulations as "the rational selection of the primary things according to nature." The Stoics' specification of what happiness consists in cannot be adequately understood apart from their views about value and human psychology.”

- ↑ Chrysippus (c.280—207 BCE), Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, April 12, 2001. Retrieved on 2010-04-27. “Once he was asked to advise an instructor for a someone’s son. His response was “Me; for if I thought any philosopher excelled me, I would myself become his pupil.””

- ↑ Stoics, lovetoknow Classic Encyclopedia, 2010-04-27. Retrieved on 2010-04-27. “The representative of this tendency, Chrysippus, addressed himself to the congenial task of assimilating, developing, systematizing the doctrines bequeathed to him, and, above all, securing them in their stereotyped and final form, not simply from the assaults of the past, but, as after a long and successful career of controversy and polemical authorship he fondly hoped, from all possible attack in the future.”

- ↑ Somatophylax Alexandros. King Leonidas of Sparta, The Hellenic World, Jan 18, 2003. Retrieved on 2010-04-27. “Leonidas, king of Sparta, was made famous in the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC. In a suicide mission designed to slow down the Persian advance towards the heart of Greece, Leonidas led a small contingent of 300 Spartans, along with thousands of allies, to guard the Pass of Thermopylae (Pillars of Fire, or Hot Gates). When the situation became hopeless, Leonidas dismissed all the allies and only the 300 Spartans remained. They held the Persians for days. Their tight phalanx wall and discipline were no match for Persian skill, but they were outnumbered a thousand to one. They fought to the last man and died at the pass, with their king.”

- ↑ Scaevola, Heritage History, 509 BCE. Retrieved on 2010-04-27. “Mucius Scaevola was a young Roman who formed a plan of saving Rome by assassinating Lars Porsenna in his camp shortly after the foundation of the Republic (approx 508 B.C.). When he was caught he was brought before Porsenna but defied him by burning his right hand in a fire and swearing eternal vengeance on all enemies of Rome. Porsenna was so impressed with his bravery that he agreed to make a treaty with Rome.”

- ↑ "Citizenship participation". “Note: propertied men were generally the only persons at these meetings (although many may have consulted their wives and sisters for input); only later did women get the right to vote in the early twentieth century in the U.S.”

- ↑ Kendra Cherry. What Is Emotional Intelligence? Definitions, History, and Measures of Emotional Intelligence, About.com, 2010-04-27. Retrieved on 2010-04-27. “1930s – Edward Thorndike describes the concept of “social intelligence” as the ability to get along with other people.”

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Peter Salovey and John D. Mayer. Emotional intelligence, Baywood Publishing Co. Inc., 1990. Retrieved on 2010-04-27.

- ↑ Daniel Goleman. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ – 1996, danielgoleman website, 1996. Retrieved on 2010-04-28. “New York Times science writer Goleman argues that our emotions play a much greater role in thought, decision making and individual success than is commonly acknowledged. He defines “emotional intelligence”?a trait not measured by IQ tests?as a set of skills, including control of one’s impulses, self-motivation, empathy and social competence in interpersonal relationships. Although his highly accessible survey of research into cognitive and emotional development may not convince readers that this grab bag of faculties comprise a clearly recognizable, well-defined aptitude, his report is nevertheless an intriguing and practical guide to emotional mastery.”

- ↑ Petri Liukkonen. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), books and authors (Kuusankosken kaupunginkirjasto 2008), 2010-04-22. Retrieved on 2010-04-22. “According to an anecdote, Kant's life habits were so regular, that people used to set their clocks by him as the philosopher passed their houses on his daily walk - the only time when the schedule changed was when Kant read Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Emile, and forgot the walk.”

- ↑ Kendra Cherry. Hierarchy of Needs: Self-Actualization and the Hierarchy of Needs, About.com: Psychology, 2010-04-23. Retrieved on 2010-04-23. “What exactly is self-actualization? Located at the peak of Maslow’s hierarchy, he described this high-level need in the following way:”

- ↑ Passer, Michael W; Smith, Ronald E; Atkinson, Michael L; Mitchell, John B; Muir, Darwin W.. "Psychology: Frontiers and Applications", McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited, 2003. Retrieved on 2010-04-28. “ISBN 0-07-089188-5”

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund; ed. McLintock, David. "Civilization and Its Discontents", Penguin Books Ltd., 2002. Retrieved on 2010-04-28. “ISBN-13: 978-0-141-18236-0 ISBN-10: 0-141-18236-9”

- ↑ Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, NPR, 2010-04-28. Retrieved on 2010-04-28.

- ↑ The Adlerian Society (U.K.), Adlerian counseling, Alfred Adler, The Man and His Work: Individual Psychology and Adlerian Counselling

- ↑ Stein, Henry T., Developmental Sequence of The Feeling of Community

- ↑ The Adlerian Society (U.K.), Basic assumptions of individual psychology, Alfred Adler, The Man and His Work: Individual Psychology and Adlerian Counselling

- ↑ Kendra Cherry. Psychology, about.com, 2010-04-28. Retrieved on 2010-04-28. “There are wholes, the behaviour of which is not determined by that of their individual elements, but where the part–processes are themselves determined by the intrinsic nature of the whole. It is the hope of Gestalt theory to determine the nature of such wholes” (1924).”

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/232098/Gestalt-psychology, Encyclopedia Britannica, 2010-04-28. Retrieved on 2010-04-28. “school of psychology founded in the 20th century that provided the foundation for the modern study of perception. Gestalt theory emphasizes that the whole of anything is greater than its parts. That is, the attributes of the whole are not deducible from analysis of the parts in isolation.”

- ↑ ISRAEL: Einstein Declines, Time magazine, 1952-12-01. Retrieved on 2010-04-28. “The next day he wrote to Eban that he was deeply touched by the Israeli offer, but never undertook functions he could not fill to his satisfaction. He liked studying the physical world, he added, but, "I have neither the natural ability nor the experience to deal with human beings."”

- ↑ Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche. The Buddha Wasn't a Buddhist, Huffington Post, April 14, 2010. Retrieved on 2010-04-28. “If we want to be free of the pain we inflict on ourselves and each other -- in other words, if we want to be happy -- then we have to learn to think for ourselves. We need to be responsible for ourselves and examine anything that claims to be the truth. That's what the Buddha did long ago to free himself from his own discontent and persistent doubts about what he heard, day after day, from his parents, teachers, and the palace priests.”

- ↑ Rick DelVecchio. Oakland: Taoists to come together for first major conference outside China, San Francisco Chronicle, October 29, 2004. Retrieved on 2010-04-28. “Tolerance is actively embracing the other person's difference." Taoists believe such events help create conditions for individuals to act in harmony. The work can achieve quantifiable results, Hon said, citing a sacred dance ritual he performed with composer Philip Glass last year at an interfaith church in New York.”

- ↑ Teresa Carpenter. Therapy or Seduction?, The New York Times (book review), April 10, 1994. Retrieved on 2010-04-28. “Her notes seem to indicate that it was she who planted the suggestion in Lozano's mind. With role-playing games and flashcards, the author writes, she reduced him to the emotional age of 3, the better to cure him.”

- ↑ Wendy Steiner (book reviewer) Martha C. Nussbaum (author of book Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions reviewed). The Philosophy of Love., The New York Times, November 18, 2001. Retrieved on 2010-04-28. “THERE was a time, not long ago, when academic philosophers paid scant attention to matters of the heart. All that has suddenly changed. Who would have predicted during the hangover of logical positivism that the love of wisdom would morph into wisdom about love? ... Her central claim is that emotions like love and grief, far from irrational distractions, are intelligent responses to the perception of value.”

- ↑ Edwin Curley (editor and translator). "A Spinoza Reader: The Ethics and Other Works", Princeton University Press, 1994. Retrieved on 2010-04-23. “see pages 214-215”

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Adam Cash Ph.D.. "Psychology Readings", John Wiley & Sons Publishers, 2002. Retrieved on 2010-04-23. “ISBN:978-0-7645-5434-6”